The inside story of how 'Oliver & Company' surprisingly saved Disney animation

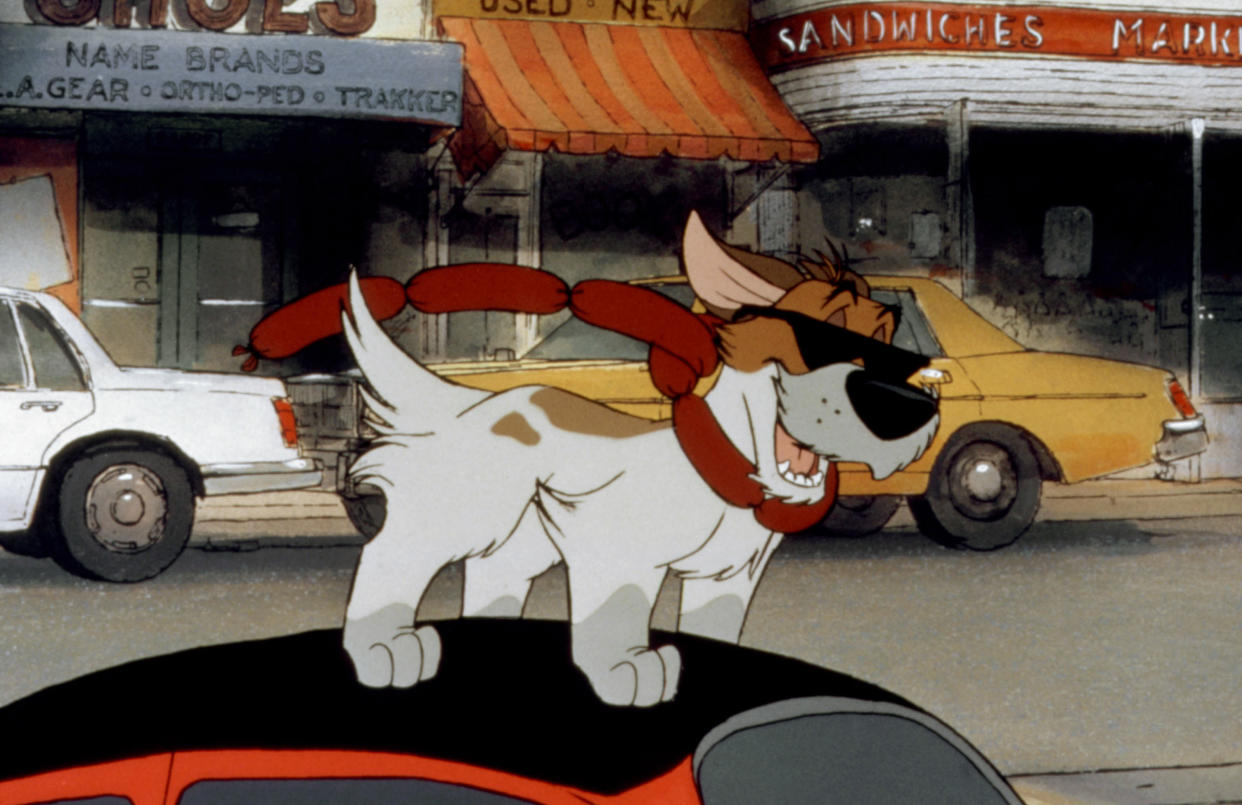

If Disney fans were asked to name the studio’s most significant animated films, few would immediately arrive at Oliver & Company. The 1988 animated adaptation of Oliver Twist, in which a cast of streetwise cats and dogs sings songs by Billy Joel, Barry Manilow and Huey Lewis, hasn’t lodged itself in popular culture quite the same way that other Disney musicals have. Admittedly, the film occupies a strange place in the Disney canon, reminiscent of the studio’s older dog-and-cat films (Lady and the Tramp, 101 Dalmations, The Aristocats) but with an ’80s pop score. It’s also the last animated feature released by Disney before the period known as the “Disney Renaissance,” the revival of the studio’s classic hand-drawn fairy-tale musicals that began with 1989’s The Little Mermaid and ended with 1999’s Tarzan. Oliver & Company doesn’t have the detailed fantasy artwork and Broadway-style score that would define Disney’s new era. And yet without it, Disney’s new era might never have happened.

Longtime Disney animator Glen Keane — the artist behind characters like Ariel, the Beast and Aladdin — remembers it well. When Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg took over the faltering film studio in 1984, Disney’s animated films had fallen out of favor with audiences. The new producers were ready to close up shop on the legendary animation department … unless Oliver & Company succeeded. When we spoke with Keane earlier this year about his Oscar-winning animated short Dear Basketball, Yahoo Entertainment asked him to share his memories of making Oliver & Company, which turns 30 this week. Here, in Keane’s words, is the story of how the scrappy dog musical saved Disney animation and paved the way for The Little Mermaid.

Glen Keane: I remember that was a turning point in Disney history, because there was a question whether animation would continue or not. There was a whole change in management: Michael Eisner and Jeffrey Katzenberg came into the studio, they inherited this animation department. It’s expensive to run. Do we need to keep doing animated movies? We were moved off the Disney lot into some warehouses in Glendale. The old building that Walt had built was no longer ours. And there was a question that maybe we won’t continue with animation anymore. You knew it was true because everyone carried their belongings out in cardboard boxes to their little warehouse. And the first movie we were working on was Oliver & Company.

But what happened right at that time was, there was this film An American Tail that came out, and it was not Disney, it was Don Bluth. And it made more money than any [non-Disney] animated film in history at that point. And I think that triggered a competitive spirit in Jeffrey, that somebody else is beating us at our game. We should be the ones out front! He was determined to compete. So he threw himself into the making of Oliver & Company. Jeffrey Katzenberg would sit in on our meetings. I was amazed — I thought, “OK, this big-shot studio executive is going to come in here and he’s going to tell us what to do, how is this going to work?” I was amazed at his creative ideas. He was like an animator. He was wonderful, in that Jeffrey Katzenberg abrasive way. I really liked the new energy he was bringing to it.

Oliver & Company ultimately made more money than any animated film in history. [The film made $53 million during its initial theatrical run and was among the 20 highest-grossing movies in a powerhouse year that included Rain Man, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Coming to America, Big and Die Hard.] When Jeffrey succeeded in that, I realized, “Wow, this is actually happening.”

But it [the film that launched the Disney Renaissance] still needed to be a fairy tale. I think each studio has, in some ways, the essence of who they are. I’d say Pixar might be, “Wouldn’t it be cool if?” You know, “Wouldn’t it be cool if these toys came alive in the films?” I think Disney is, “Once upon a time.” That’s the heart of it.

And it wasn’t until we were going to do a fairy tale that we knew we were planting a new flag in some way. On Little Mermaid, Howard Ashman and Alan Menken were there in the studio, and you could hear Alan playing the piano down at the end of the hallway. You felt it. Before the movie came out, you knew we were back. Something new was happening, and it wasn’t the same. We weren’t re-doing anything, we weren’t trying to relive the past, we were doing it in our own way. I mean I’ll never forget that. I was about 33 years old I guess, feeling like, “This is my time. It’s my time to be me.”

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: