New exhibit tells Patty Loveless' Nashville story and the influences that fueled her

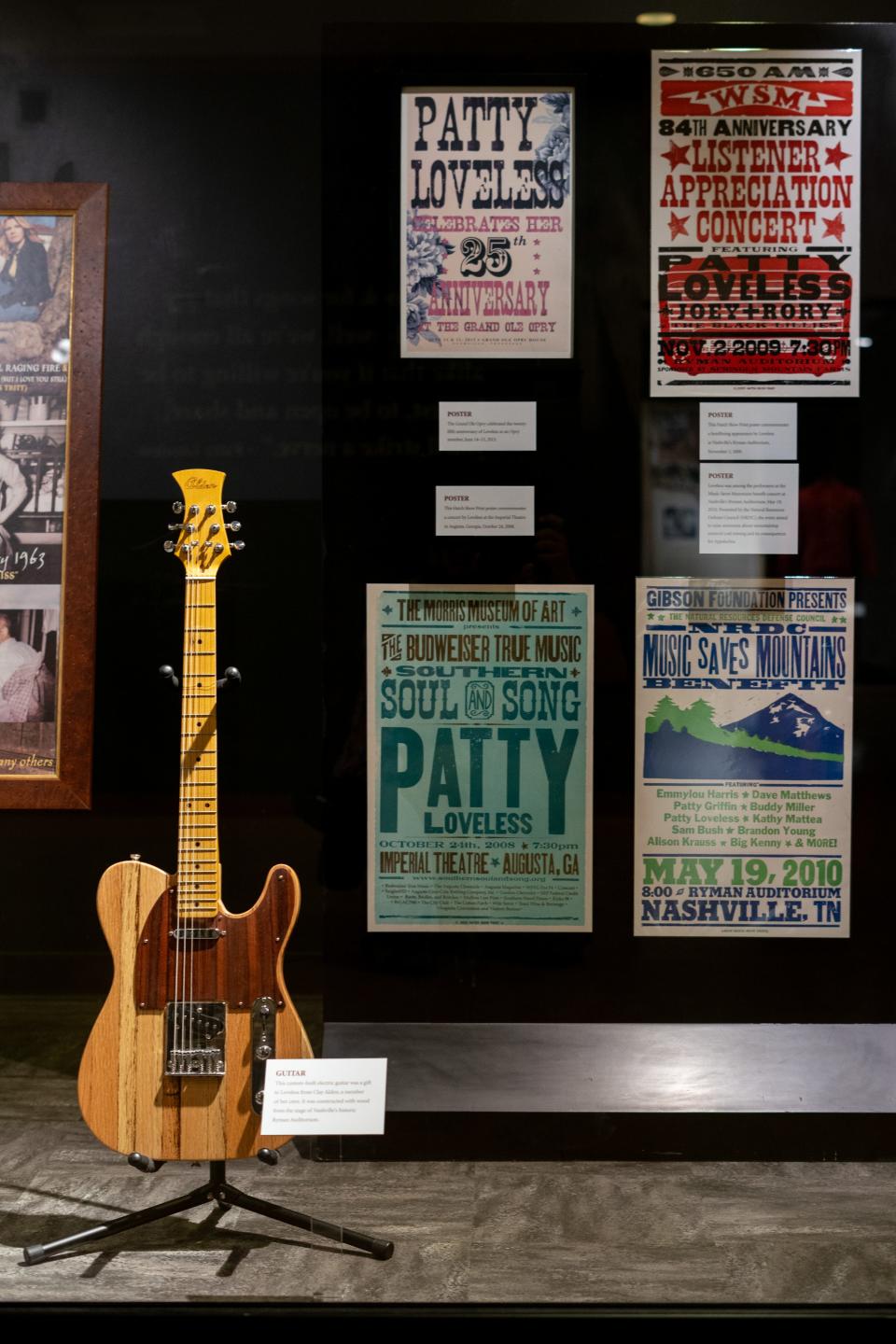

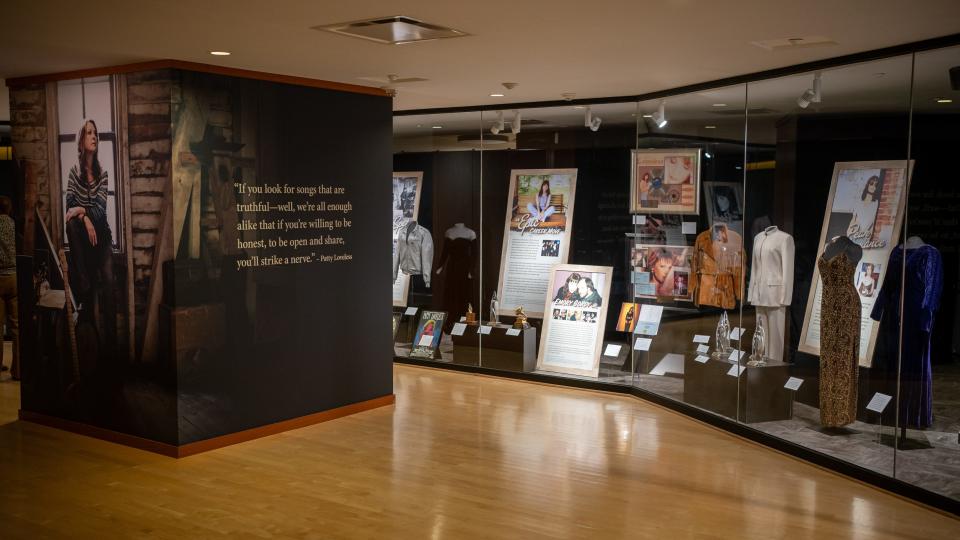

Grammy-winning Grand Ole Opry member Patty Loveless' 2023 Hall of Fame induction-worthy career as a peerless country music creator is being celebrated in a new exhibition, "Patty Loveless: No Trouble with the Truth" opening at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

The exhibit, which will be open from Aug. 23, 2023, through Oct. 2024, is included with museum admission.

The Kentucky-born artist is in a rare class of talent able to seamlessly walk the line between country's twin desires to achieve pop acclaim while retaining its rootsy, rural-borne heritage. This skill allowed her career to sustain numerous personal and professional issues. The strength of her art -- outstanding in a class alongside other singer-songwriters like Matraca Berg, Vince Gill, Jim Lauderdale, Ricky Skaggs, and Marty Stuart, among them -- afforded her a run of No. 1 country singles from 1989's "Chains" and "Timber, I'm Falling In Love" to 1996's "Lonely Too Long."

Loveless' most significant talent was as a singer-songwriter whose awareness and value of the power of lyrics directly impacted her writing process and ability to convey lyrics in recordings and onstage.

While in conversation with The Tennessean at the exhibit's Tuesday night opening, Loveless cited names including the 1987 "Trios" album collection of creators -- Emmylou Harris, Dolly Parton and Linda Ronstadt -- as well as countrified pop-rock icon Bonnie Raitt, as key influences in her desire to hone her talents.

"Country's a genre that celebrates the value of a story in a song in heart-wrenching songs," added Loveless, who added bluegrass godfather Dr. Ralph Stanley and the Stanley Brothers to her list.

Upon arriving in Nashville after her divorce from her first husband, drummer Tony Lovelace, she spent five years developing her craft as fellow neotraditionalist-leaning male artists like Randy Travis surged to the forefront. Loveless' unique blend of sonic influences being both rootsy and pop -- but decidedly more the former than the latter -- allowed her to become a gold-selling album artist who drew strong comparisons to "golden era" stars like Patsy Cline.

For the artist, the difference between cutting then-contemporary uptempo songs familiar to catalogs of artists like MCA Records label-mates The Judds and Trisha Yearwood, like 1985's "Lonely Days and Lonely Nights" to 1988's cover of George Jones' then two-decade-old single "If My Heart Had Windows" was noteworthy.

However, in an era where slick pop-aimed production and increased crossover appeal spelled platinum-selling success for women in the genre, Loveless was more often than not a gold-selling performer.

By 1993, she had moved to Epic Records. Two years later, she began a run where she closed out the 1990s as the Academy of Country Music and Country Music Association's female artist and vocalist of the year.

"Singing songs like ["If My Heart Had Windows"], 'How Can I Help You Say Goodbye' (1994) and "Lonely Too Long" (1996) that felt more in tune with the lyric-driven music I was raised listening to by Dallas Frazier, Jones, Connie Smith. This allowed me to create songs communicating directly with people and touching their hearts."

She's sung numerous songs that have impacted those grieving the loss of loved ones to cancer or other fatal illnesses. Dig deep into her catalog and a late-era Loveless cut -- her 2001 version of Darrell Scott's "You'll Never Leave Harlan Alive" (released a half-decade prior) -- highlights how she was empathetically able to cut songs that impacted people going through such a particular moment in their lives.

Scott played the banjo on Loveless' version of the bluegrass-tinged traditional country ballad that tells the story of a Harlan County, Kentucky lawman whose tombstone is inscribed with the phrase that later became a single. Before Loveless cut the song, West Virginian Brad Paisley re-cut it, interpreting the lyric as an homage to the tragic work of coal miners in Appalachia.

In a 2020 interview, Scott recalled Loveless' second husband (she and the legendary producer have been married since 1989) Emory Gordy, Jr., placing a photo of the singer's coal miner father on a music stand while she recorded the song. Gordy asked Loveless to sing the song with the memory of her father, John Ramey -- who died from complications related to black lung disease in 1979 -- on her heart.

Two decades later, the song's revival by Chris Stapleton -- another Kentuckian inspired by Loveless' legacy -- spurred numerous onstage performances for the now largely semi-retired singer, including alongside Stapleton at 2022's Country Music Association awards.

Gordy attended Tuesday's ceremonies alongside Joe Galante at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. The 2022 Country Music Hall of Fame inductee and her boss at MCA Records. Also, singer-songwriter Berg, producer Tony Brown, pianist Glen D. Hardin and more were in attendance.

Loveless then makes a note of highlighting that her Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum exhibition is also a highlight to the numerous people who helped her along the way, directly pointing at artifacts from her and her brother Roger's (they sang together as The Singing Swinging Rameys) teenage inspirations, the Arkansas-born Wilburn Brothers, plus key influences like Porter Wagoner.

About soon-to-be fellow Hall of Fame inductee Vince Gill, she cites his perpetual influence keyed by her and her brother, having arrived again in Nashville -- after a teenage trek to Music City to pursue success -- playing his 1984-released debut solo EP often as they settled into a less-than-ideal hotel off Briley Parkway.

Fascinatingly, the EP was produced by Gordy, who would later become Loveless' husband.

Stunned by seeing Gill at CMA's Fan Fair later that year, she approached him, introduced herself and giddily noted that they would eventually be singing together.

In under a decade, they began to appear as background vocalists on each others' projects frequently.

"I've been singing along to Vince's music for almost 40 years now," Loveless joked.

While staring at her career as a retrospective celebrated behind glass in country music's most vaunted exhibition hall, Loveless thinks about the most significant value of her personal effects being showcased at this point of her career.

"We all have dreams and you have to remain dedicated -- regardless of what happens -- to those dreams. There's a generation of artists out there like Carly Pearce and Carrie Underwood who look at my career with the same awe that I consider the work of artists like Brenda Lee, Loretta Lynn, Dolly Parton and Connie Smith -- I mean, we'll never stop being in awe of each other. If we all stay true to our dreams, we'll all share a place in [the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum] one day."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Country Music Hall of Fame exhibit tells Patty Loveless' Nashville story