"Some people said that seeing the band again made their lives complete": Remembering Status Quo's Rick Parfitt

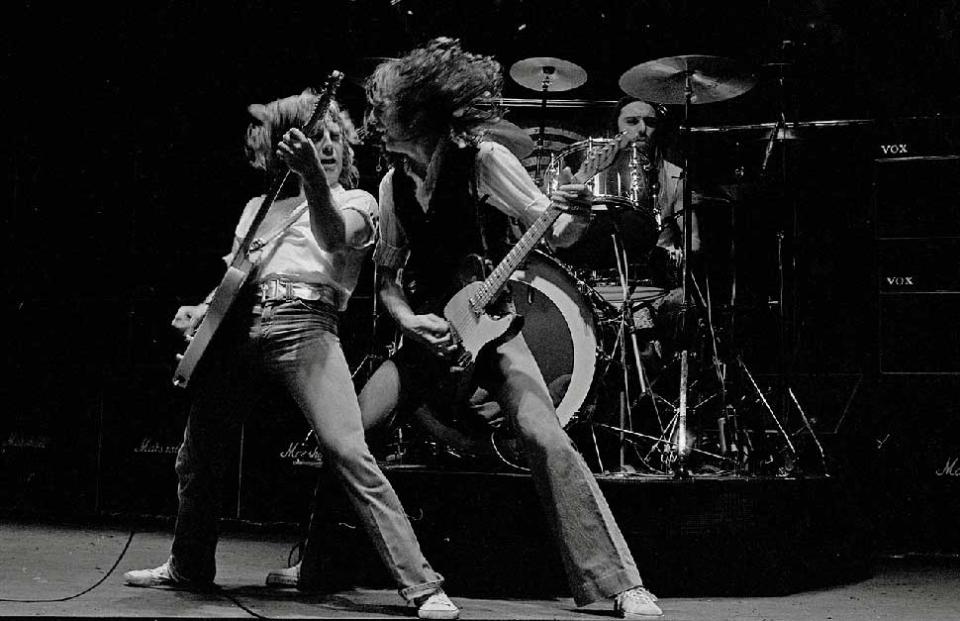

It was among the coolest sights in rock’n’roll: Rick Parfitt, Francis Rossi and Alan Lancaster in alignment at John Coghlan’s drum riser, legs akimbo and heads down, long hair flailing in time to the beat. From December 1972’s Piledriver to Blue For You four years later, bookended by the seismic concert double album Status Quo Live!, these South Londoners became untouchable at what they did. With a hard-rocking boogie style that was pretty much unique, the so-called Frantic Four ticked all of the boxes: sound, songs, look, banter and attitude, they had it all. Three of those five studio records topped the UK chart, often slamming straight to the top spot.

The phrase ‘band of the people’ is used often, but few deserved it more than Status Quo, worshipped by a legion of denim-clad followers, but in their heyday scorned at every turn by the same media that now considers them cute cultural darlings.

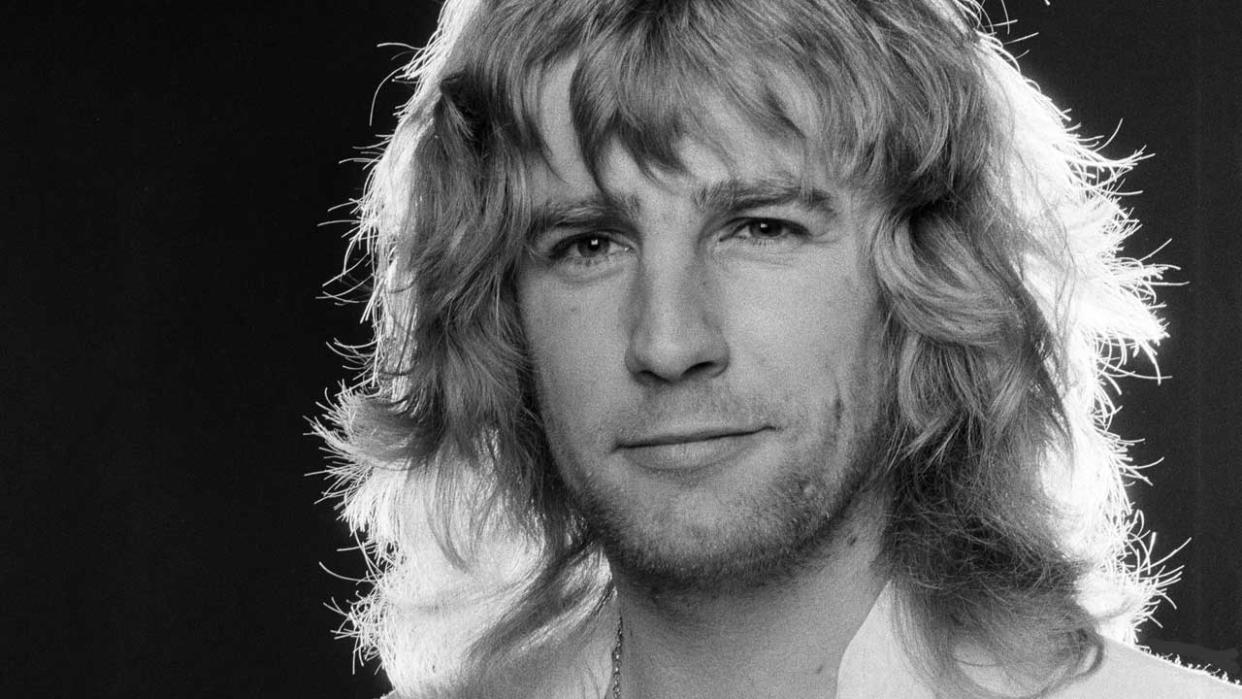

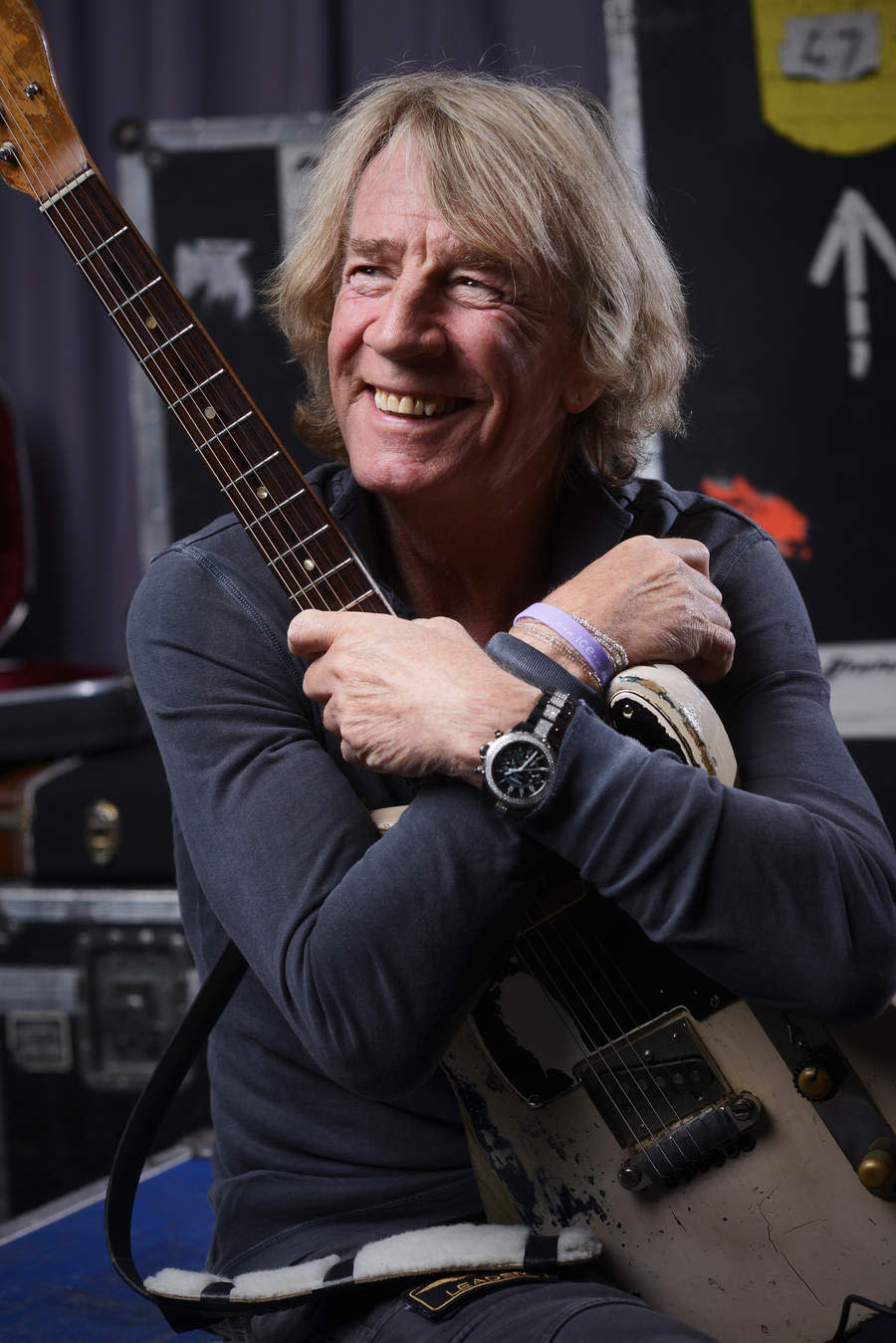

Although Rick Parfitt left the between-song chatter to Rossi, his role in the band was every bit as vital. Shirt opened to the navel, white Fender Telecaster raised at a 45-degree angle, his rhythm hand a blur and his face etched into a perpetual laddish grin, Parfitt’s relative silence only enhanced the band’s mystique.

To the eyes of the world, for almost 50 years Rossi and Parfitt, although they were very different as people, spelled a duo, in their own way as famous as fish & chips and Morecambe & Wise.

Although I would never presume a genuine friendship between us, over the decades I developed a much-cherished professional relationship with Rick, who often picked up the receiver and sang Chuck Berry’s My Ding-A-Ling when he knew I was calling for an interview. His memory sometimes failed him, but he was amiable, generous with his time and surprisingly modest. And, in stark contrast to Rossi, who once famously dismissed Quo’s output during the 1970s and early 1980s as “a few moments of brilliance and sixty-to-seventy per cent shit”, Rick absolutely loved the band’s Frantic Four era. But we’ll come to that later.

Long before our many journalistic exchanges, I first met Rick Parfitt as a fan. Quo were playing seven shows at London’s Hammersmith Odeon as part of a tour for their anniversary album 1+9+8+2, and I had tickets for every night, having camped out several months earlier to acquire the best seats possible. My gig buddy Nigel Glazier and I had waited around at the stage door, and sure enough a few hours before show-time, Rick bowled up, looking unshaven and typically dishevelled. He invited us to step inside, signed our LP sleeves, answered a few silly, starstruck questions and posed for a photograph. Conducted with such casual grace, those few moments were absolutely priceless.

In the summer of 1986 I experienced a very small taste of what it was like to be a part of the Quo entourage, travelling with them for an ‘on the road’-style piece on board a tour bus from London to St James’ Park in Newcastle where they performed as special guests to Queen in front of 38,000 fans. When the bus pulled in to a motorway service station, I followed a few discreet paces behind the disembarking Parfitt and Rossi.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, given that this was just a year after the band had opened Live Aid at Wembley Stadium, the disbelief of the public was universal, from young and old, male and female. Rick and Francis handled it all with customary good cheer, autographing petrol bill receipts or newspapers, all the while nodding and smiling. With millions of records sold and a record-breaking run of hits, Quo were now a so-called national treasure.

“Meeting the fans is rarely a chore unless people follow you around like a piece of meat: ‘There it is – ask it for a photograph, get its autograph,” Rick once told me, adding with a grin: “When people stop asking for them, that’s when you have to worry.”

Richard John Parfitt was born in Westfield, just outside of Woking, on London’s leafy outskirts, on October 12, 1948. His gregarious nature was probably inherited from an insurance salesman father who gambled and sank a few pints. Before his eleventh birthday Ricky told his mother, who worked in local cake shops, that he wanted to go “into entertainment”. She had bought him a piano at the age of seven, and he began playing guitar three years later. At the age of 11 Parfitt made his TV debut on a show called Midwinter Music, singing Cliff Richard’s 1959 chart-topper Travellin’ Light, which led to him being dubbed ‘Woking’s budding Tommy Steele’.

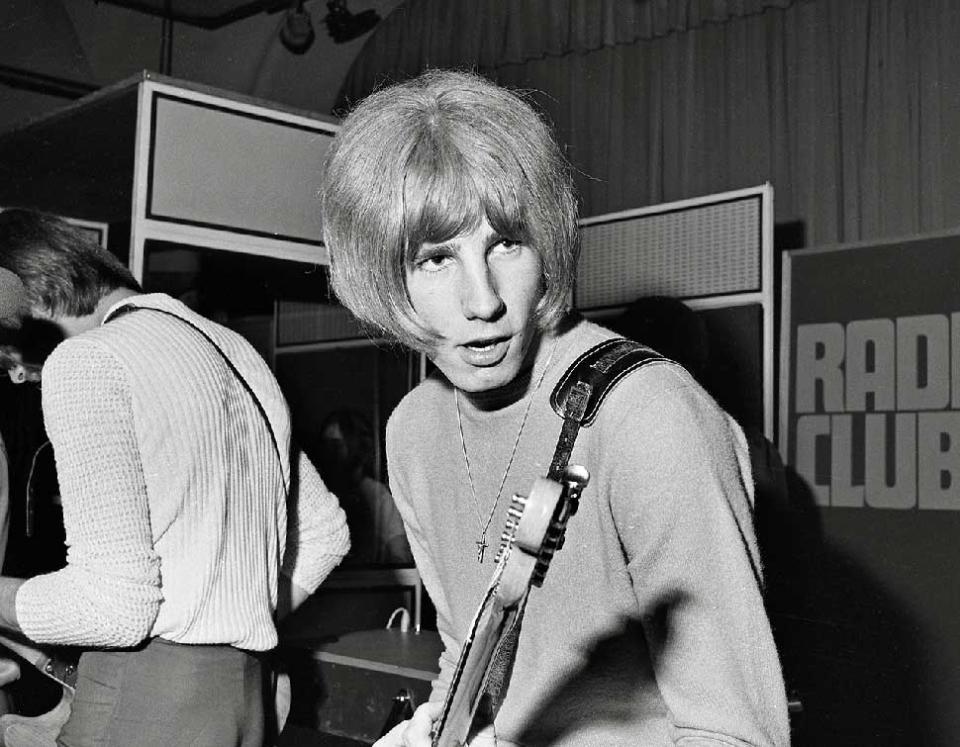

Having adopted the stage name Ricky Harrison, he joined the cabaret trio The Highlights, completed by the twins Jean and Gloria Harrison. It was at Butlin’s holiday camp in Minehead in the summer of 1965 that fate played its hand. Parfitt had been booked for a residency with The Highlights at the same time as a four-piece group from South London called The Spectres, whose line-up included Rossi, Lancaster, Coghlan and newly arrived keyboard player Roy Lynes (who had replaced Jess Jaworski shortly before the start of The Spectres’ own summer season). When his own set was done, Rick often looked in on The Spectres in the Rock Ballroom.

“I remember wandering over there one afternoon and watching them for the first time,” he later told me with a grin. “I may still have been in my silver lamé suit, which I wore all the time. They were playing Bye Bye Johnny and it sounded absolutely fantastic.”

“My first impression of Rick Parfitt was that he was a flash poof,” Rossi said many years afterwards. “And he’s still flash – he’s an only child who grew up in cabaret. He was more showbiz than Alan, John or I. Rick would really camp it up.”

Parfitt didn’t join The Status Quo (as they had become known) until 1967, by which time were enjoying their first Top 10 hit with Pictures Of Matchstick Men. After a flirtation with flower power the band toughened up the music, shed the keyboards, grew their hair and began wearing the scruffiest clothes available, and dropped the ‘The’ from the band’s name for a pair of watershed albums: Ma Kelly’s Greasy Spoon and Dog Of Two Head, in 1970 and ’71.

It wasn’t until 2013, when Universal Records hired me to write extensive liner essays to accompany a catalogue overhaul, that Rick and I got to talk about Quo’s music in real trainspotter-esque detail. His love of the May 1974 album Quo, which many fans consider the group’s heaviest record, was apparent. “When we wrote Drifting Away, it sounded so, so heavy,” he recalled gleefully. “That rhythm was constant, right in your face; it was just such a turn-on. That’s where my head was at back then, you know: ‘Just let it fucking rock.’”

In many ways, Status Quo Live! spelled the end of an era. Over three hot and sweaty nights at Glasgow Apollo, the massed jumping of loony Scottish fans caused the balconies to move by as much as three feet.

“I was very conscious of it being the band’s time – a golden era, if you like,” Parfitt told me. “Looking back, it probably couldn’t have got much better. We were selling shitloads of records and the gigs were packed out, across Europe but particularly in England. We were the flavour of that year.”

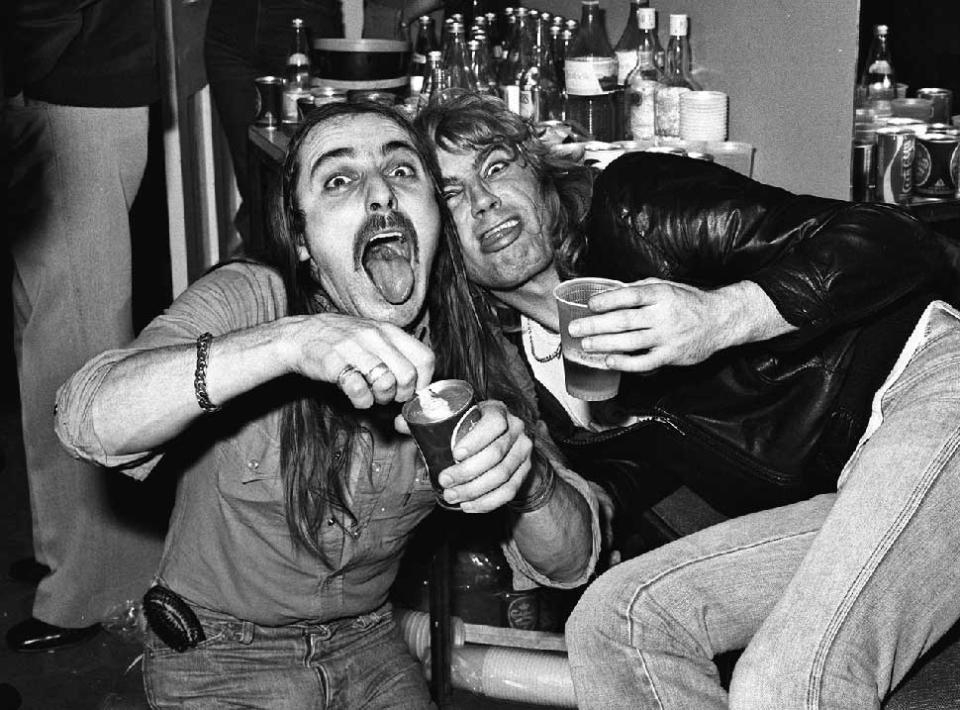

However, Quo’s climb to the top had a darker underbelly, and Rick – who cannot even recall being at Live Aid – threw himself into the role of the debauched rock icon. From the outside, and verbalised with such nonchalance, these shenanigans probably sound like harmless schoolboy fun, but Parfitt’s behaviour became so depraved that he once referred to himself as “a bit of an ogre”.

“Richard, my eldest son, saw me at my worst,” he admitted to writer Simon Hattenstone in 2007. “It was a big shock for him and he deserted me. I don’t blame him, ’cos I was just not with it, I wasn’t here… Richard has described me as turning into a Mr Hyde. He said: ‘You became a different person, and it was almost like being out of a movie where you’d wake up and all the facial hair had gone and the claws had been drawn back, and you’re this normal person for a very short space of time until you decide to drink the potion again.’ For three or four years he didn’t talk to me, and he came back to me at about fourteen. Wisely, his mother kept him away from me.”

Like many other long-term disciples, I fell out of love with Quo during the mid-80s and throughout most of the following decade. Parfitt stayed along for the ride, but he wasn’t always entirely happy.

“From Rockin’ All Over The World onwards, for us as a band, everything got a little too… posh,” he told me during a career retrospective-based interview back in 2001.

It’s also worth noting that Lancaster also cites RAOTW as a turning point. “Back then Quo was almost like a religion to the fans,” the bassist once told me. “To the band it was like being in a football team – you were allowed to have the occasional bad game, but nobody wanted to hear us playing netball.”

Back in that 2001 interview, as we flicked through my assorted vinyl LP sleeves, Rick shrugged indifferently at In The Army Now (“the title song was great, but it had too many fillers”), and emitted a pronounced wince as I held out Ain’t Complaining (“My hair had got too short and the music was too polite. There was no weight behind what we were doing, the edge had gone. We weren’t real any more”).

Although Rossi would frequently state his belief that John ‘Rhino’ Edwards was a better bass player than Alan Lancaster, who had settled out of court with the band after what Lancaster later called the “conspiracy to get rid of me”, Edwards lacked the star quality vital for such a crucial role.

In another of our interviews, Rick professed discomfort at Lancaster’s enforced exit from the group. “Francis and Alan were both friends of mine, I was on the fence,” he told me. “But everyone knew that things were going sour within the band. And there’s nothing worse than going on stage and being unable to look one another in the eye any more.”

During this period of uncertainly, Parfitt recorded a solo album, Recorded Delivery, which was never released, although many of its tracks were used by the newly revived Quo as the B-sides of singles. A decade later, Rossi’s solo debut, King Of The Doghouse, did make it into the racks but failed to sell in large quantities.

Nobody would have predicted the possibility of Rossi and Parfitt playing again with Lancaster and Coghlan. Francis had once joked that such a reunion was “like trying to get your dick up your own arse – impossible”. However, with Rossi and Lancaster burying their differences, the Frantic Four met again in the touching conclusion of Alan G Parker’s film Hello Quo, sharing a group hug in a car park at Shepperton Studios before performing a few numbers together.

“Standing in a circle and putting our arms around one another again was just… lovely,” Parfitt later told me, almost lost for words. “Let alone plugging in the gear and playing together. After so long apart that was quite surreal.”

Hysteria greeted the news that the first time in public for more than three decades the four-piece, keyboard-less line-up of Quo was to perform six UK shows in March 2013. A few days after the announcement, I spoke to Parfitt, who had been keeping abreast of the furore among the fans.

“There’s been plenty of excitement, hasn’t there?” he said, smiling. “This reunion will attract back a lot of our fans from the seventies, the ones that lost faith when we stopped doing what we should have been doing and began making covers albums.” Those last few words were voiced with clear disdain, and he added: “I hope that’ll be the case, anyway.”

In late 2012, on the morning that the band collected a gong at the Classic Rock Awards, I discussed the rebirth of the classic line-up with all four of its members. The first pre-sale of Frantic Four reunion tickets had become available just hours earlier, and like everyone else Rick was buzzing: “They [the tickets] sold out in ten minutes, apparently,” he beamed.

“I’m still finding it pretty mind-boggling that we’re all here together,” Rick added. “I just said to Nuff [Lancaster] that walking around the streets again with these guys actually feels bizarre. I’m sitting here and I’m feeling like the ‘new boy’ all over again. I mean, these three started it all up.”

When asked why the reunion was finally happening, Rossi cut to the chase: “Well, if it didn’t happen soon then it probably never would. I mean, look at us – we’re old men.” (Rossi and Lancaster were both 63 at the time, Parfitt a year older and Coghlan 66). However, the love in the room was evident. “It’s quite a shock when the four of us get back together, all straight, and sit around a table,” Rick pointed out, adding, sage-like: “Perhaps after all these years we’ll finally get to know one another for the first time.”

The Frantic Four tour began on March 6, 2013 in Manchester. As well as attending both of the band’s Hammersmith gigs and the show at Wembley, I travelled to Manchester for their second show, at the Apollo. Though the set-list was relatively short, it was a dream come true for true-blue purists: nothing post-1976, and unofficial fifth member Bob Young strode on from the wings to play blues harp on Railroad and Roadhouse Blues. The performance was greeted by scenes of teary-eyed disbelief. As the band soaked up the applause, Parfitt spotted me in the balcony, dead-centre of the front row, and gave a cheery wave.

My review of the show for Classic Rock began with the words: “Led Zeppelin at the O2 Arena?! Pfft!” And just for once the press, including representatives from The Times, The Telegraph and The Independent, reflected the excitement of the paying punters with a slew of kind words. “It was cred time for Status Quo again,” Parfitt chuckled, tongue firmly in his cheek, when we discussed the across-the-board praise.

Given all of the above, few expected Rossi to dismiss the Frantic Four’s comeback as “a fucking mess”, but that’s exactly what happened. In an interview with Classic Rock the guitarist slated Coghlan for being “unfit” and “slowing down” the beat. Rossi also reiterated past criticisms of Lancaster, calling his childhood friend “not as good a bass player as John Edwards”, and summing things up with the statement: “It was so sloppy at times that I cannot see why the fans loved it.”

Parfitt told me he shared Rossi’s belief that there was “room for improvement”, but “didn’t really understand Francis’s [negative] comments”. He had felt “the immense excitement and thrill of going out on tour again with Alan and John”, and admitted: “I enjoy the current Quo, but I hadn’t felt anything like it for years. [Those shows] had that raggedness that the fans wanted.”

On a second Frantic Four tour the band were tighter, and consequently Rossi enjoyed it more, but the set-list was a little too safe. Within a week of ending in Dublin, Parfitt and Rossi were in Denmark with the band that cynics had begun to refer to as ‘Quo Lite’. Rick returned to life as one half of that band stating: “After thirty years the fans were able to dig out those faded denim jackets and wear them with pride again. We gave them exactly what they wanted to hear. Some people said that seeing the band again made their lives complete… it’s not till hearing something like that that you appreciate things fully.”

However, the Frantic Four’s return would exert a profound effect upon Quo Lite. To a dogged group of fans, Status Quo simply ceased to exist on the tour’s finalé on April 12, 2014. Rossi and Parfitt still toured, and their first unplugged album, 2014’s Aquostic (Stripped Bare) made the UK’s Top Five. Two years later, the novelty had worn off a little, though Aquostic II: That’s A Fact! peaked at No.7.

However, Rick was experiencing health problems that sometimes sidelined him from the band’s live shows. Even before a tour that was billed as the band’s swansong as an electric-based group, he decided not to go back, telling Classic Rock: “In my heart I’m a rocker. I’ve always been. The acoustic thing doesn’t really float my boat. If I’m going to make music, it’s got to rock.”

Being out of Status Quo broke Rick’s heart. “That’s true,” he sighed, “but I’ve got to learn to cope with it. I’m living a different life now.”

The email from the band’s publicist arrived in my inbox at 3.08pm on Christmas Eve 2016. Titled simply, ‘Rick Parfitt 1948-2016’, it began with the words: “We are truly devastated to announce that Status Quo guitarist Rick Parfitt has passed away at lunchtime today.”

I couldn’t believe my eyes. Back in the summer, Rick had generated a latest set of headlines after being pronounced clinically dead for several minutes in the wake of a concert in Turkey. Following this new heart attack – Rick couldn’t recall whether it was a fifth or sixth (“I’ve lost count”) – the doctors, who recognised that it was his third such experience, had insisted on a lengthy spell of convalescence.

Our final interview took place by phone from Spain where, to use his own words, he was taking that medical advice “very seriously”. He explained: “I’m sitting around and writing songs, having a lovely time.”

The date of that conversation was October 24, 2016, two months to the day before he passed away. Typically, he downplayed the severity of the latest attack, referring to it as “falling over” and insisting: “I would say that I’m fully recovered, and as the weeks pass I feel better and better.”

He was already laying plans for a solo record, an autobiography and also, potentially, “some shows midway through next year”. There was even time for a little gallows humour: “It’ll take more than death to kill me”, he cracked it twice during the conversation, although the second time there was a solemn postscript: “I did actually die. So now I must be responsible, another heart attack will kill me.”

And yet it wasn’t the dodgy ticker that spelled the end for one of the rock music’s all-time greatest rhythm guitarists. In his final weeks, Rick had taken a fall and was admitted to a hospital in Marbella. The injury became severely infected and he was in a lot of pain. It was a complication known as sepsis that killed him.

At 68, Parfitt had lived the equivalent of several lifetimes, earning, spending and losing millions, dating Page 3 girls, driving and collecting fast cars and enjoying the status he had earned as a Grade-A rock star. However, tragedy may have contributed to his firm embrace of celebrity’s debauched underbelly. In 1980, Rick’s daughter Heidi had drowned in the family’s swimming pool at the age of two. “Life went on and you learn to live with it, but you never get over it,” he once said.

Whatever the cause, back in October Rick was left contemplating many issues, including the price he’s paid for an adulthood filled with rock’n’roll excess.

“I’ve been somewhat selfish for most of my life,” he admitted. “I’ve lived how I wanted to live, done what I wanted to do when I wanted to do it, and nothing or nobody has stood in my way. I do things to excess, and through my forties and fifties I paid no thought to anything except having a good time. But it catches up with you.”

Besides his solo ambitions, Rick also had other plans. The much-discussed project PLC (Parfitt-Lancaster-Coghlan) was not just figment of anyone’s imagination. When I Skyped with Lancaster just hours before Rick’s tragic death, he confirmed a very real wish for the “other three”of the Frantic Four to collude again, using a Francis Rossi substitute that the bassist wasn’t prepared to name.

Nothing was set in stone, Lancaster painstakingly pointed out, but all concerned were moving forwards towards making it happen, and long-time associate John Eden had been lined up to produce. Eden had even emailed everybody about using a particular studio that he’d found.

“I’ve got four songs, but they’re good ones,” Lancaster revealed. Rick had already recorded some usable parts for at least one of these tracks, though nobody was completely sure whether they were intended for Parfitt’s own album or to be a part of PLC. Bob Young has contributed harmonica to one of the tunes.

It’s fair to say that in their later years Parfitt and Rossi grew apart. And after a half-century spent in such perpetual close proximity, that’s completely understandable. Nevertheless, Francis had a bee in his bonnet over his partner’s perceived obsession with all things macho. In 2008 Rossi told me: “Not to be vindictive or nasty, but someone got to Rick during the 1970s and since then we haven’t seen or heard the real Rick. On the early albums he wrote songs with lovely, beautiful melodies, but then he became about rock, rock, rock.”

Rossi continued: “Methinks he protesteth too much. ‘I’m not a cabaret singer.’ No, Rick, you are. He definitely ain’t this rocker that he keeps trying to be. People have laid that image at his door, but he doesn’t have to live up to it.”

However, to the general public – even to royalty – Rick and Francis came as a team. Visiting Buckingham Palace to collect their OBEs in 2010, Queen Elizabeth enquired of Rossi: “There are two of you, aren’t there?” Prompting Francis to reply: “Yeah, your Majesty. He [Rick] will be along in a minute.”

When, during an autumn 2016 interview, I asked whether it was frustrating to be defined as one half of a duo, Rossi snapped back: “Yes. Very short answer. Next question please.”

And yet when given the opportunity to criticise Rossi for carrying on without him, Rick simply shrugged and said: “Francis will do what Francis will do. I shan’t say anything to the contrary because I don’t want any bad feeling. After fifty years of travelling the world together, that’s the very last thing I want. Let them do whatever they want to do. It’ll be with my blessing.”

What Parfitt really thought of the situation we will never know, but two years earlier he had insisted: “Quo is not Quo without Francis, and Quo is not Quo without me – nor without Rhino in its front line. If either Francis or I were to go, then it wouldn’t be Quo any more.”

Even after Parfitt’s passing, with the young Irish guitarist Richie Malone as a stand-in ‘guest guitarist’, Quo announced that The Last Of The Electrics would be extended into 2017, and visiting territories missed on the previous tour. Further Aquostic gigs, including the Royal Albert Hall in London on July 1, were also booked. Rossi’s Quo, in whichever format, were not going away any time soon.

When it came a few days afterwards, Rossi’s response to the loss of his bandmate was warm, emotional and unflinchingly honest. “I was not ready for this,” he began, describing his and Rick’s relationship as “without doubt the longest of my life. This was also the most satisfying, frustrating, creative and fluid.

“Rick was the archetypal rock star, one of the originals. He never lost his joy, his mischievous edge and his penchant for living life at high speed, high volume, high risk. His life was never boring. He was louder and faster and more carefree than the rest of us. Any number of incidents took place along the way when Rick strayed into areas of true danger, and yet still losing him now is still a shock.”

Once again Francis repeated: “I was not ready for this.”

The truth is that nobody saw it coming. And it still hurts that the final words spoken to me by Richard Parfitt were: “A good recovery is my priority, but after Christmas I will be itching to do something – in the studio and on stage. I really do miss the stage."