“People thought the Beatles were God. That's not correct”: the genius of Frank Zappa, the rock’n’roll icon who had no time for rock’n’roll

May 1968: early morning in the sprawling, 18-room log cabin on the corner of Laurel Canyon Boulevard and Lookout Mountain Drive where the famous ‘freak-out’ artist Frank Zappa lives. Outside, finches and sparrows are chirping and the sun is burning off the first-light smog; inside, though, the atmosphere is still blinded and dark, the air choking with cigarette smoke.

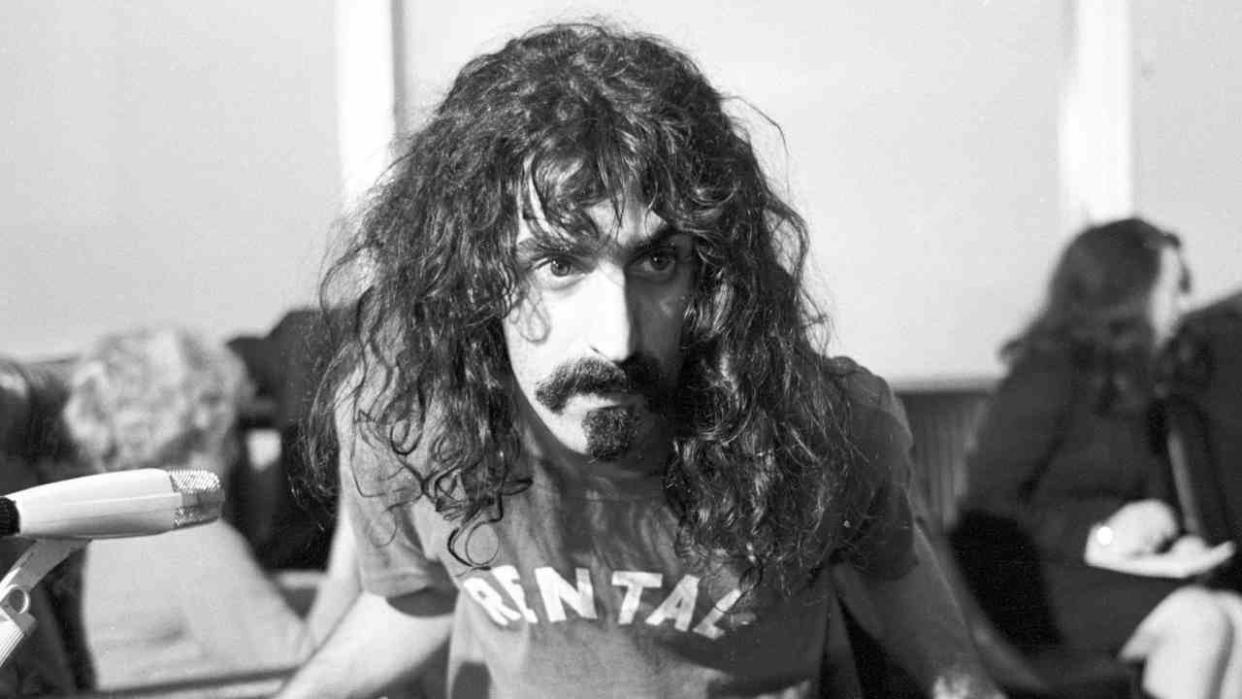

As usual, Zappa has been up all night working at the piano and desk that dominate the enormous main living area, swivelling in his chair from desk to piano and back again as he composes his masterpieces, one after the other, while guzzling strong black coffee and chain-smoking the cigarettes that have been his only drugs since he was 11 years old.

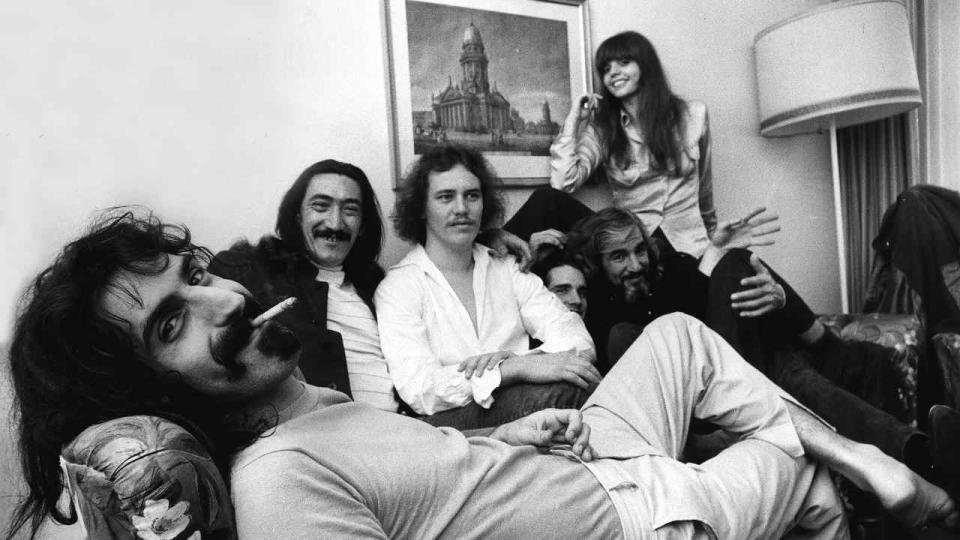

Now Frank is sleeping. As are most of the other people who share the house with him: his English secretary Pauline Butcher, his former girlfriend Pamela Zarubica, his recording engineer Dick Kunc, designer Cal Schenkel, tour manager Dick ‘Snork’ Barber, and Mothers Of Invention band members Ian Underwood and Jim ‘Motorhead’ Sherwood. Then there are those non-residents, famous and not-so, sleeping in various nooks and crannies, or just stretched out in front of the huge stone fireplace, beneath the 14-candle chandelier.

The only person up at this hour is Zappa’s 23-year-old wife, Gail, who tiptoes around the bodies with their eight-month-old baby daughter, Moon Unit, under her arm.

“Life was complete chaos,” Gail told Classic Rock in 2012. “One time I said to Frank: ‘That guy’s been here for three days and I don’t even know who he is!’ He said: ‘Don’t worry about it.’ Then you’d run into [teenage groupie] Miss Mercy with a stick of butter peeled like a banana that she’d just be eating. Oh, and a rock’n’roll band would arrive in the middle of the night and just walk in; there were no locks on the door. It was just insane.”

Going into the kitchen, where there is no floor (“I don’t know what happened, it just disappeared!”), Gail hunts for whatever food might be left to make breakfast. The stove is on a platform so high that she has to reach up to put on the frying pan. The hardest part, though, is that Gail can’t just drive to the store to buy food. “We didn’t have a car. If we had to get groceries, I hitchhiked,” she says. “I went right out the back door with my thumb out and went down to the market. I did the laundry that way too! I’d have Moon on one hip and laundry on the other… I mean, it sounds insane, but those things had to be done.”

Nothing must keep Gail’s husband from his work. For he is not just any rock musician, but a composer. And, as he explains in his semi?autobiography, The Real Frank Zappa Book: “A composer is a guy who goes around forcing his will on unsuspecting air molecules, often with the assistance of unsuspecting musicians.”

Pauline Butcher, Frank’s former secretary, speaking from her home in Singapore, recalls her boss as a formidable man. “He made it very clear he shouldn’t be interrupted if he was working. And from the minute he got up to the minute he went to bed, he would be working. We would not dare to go near him. He would raise his head from his desk or the piano and think about what you had said to him, and give you a very short, swift answer to make it clear that you were not welcome.”

As Zappa told an early interviewer: “The lifestyle that I have is probably neither desirable nor useful to most people.”

Nor, a cynic might add, was the music he composed. But then Frank Zappa neither lived his life nor made his music to please ‘most people’. He did so to please himself. And anybody who expected to remain in his orbit would have to come second to that.

Ask anyone now, 30 years after his death from prostate cancer in 1993, who Frank Zappa was and they might describe any number of people. Not just a rock star, but an avant-garde jazz musician, a classical composer, a filmmaker, a writer, satirist and university lecturer. Zappa was the guy John Lennon said he’d “always wanted to meet”; he was the record label entrepreneur who signed Captain Beefheart and produced his greatest work, Trout Mask Replica; the mentor who Alice Cooper now calls “the original shock rocker”.

And that was just in his late-60s ‘Log Cabin’ period. By the time he died, at the age of 52, Zappa had also become a pioneer of computerised electronic music, a campaigner for voter registration, and the “personal hero” Vaclav Havel wished to designate as Czechoslovakia’s cultural liaison officer with the USA. Others will simply recall him as the guy who gave his kids funny names like Moon Unit, Dweezil, Ahmet Emuukha Rodan and Diva Thin Muffin Pigeen; a man who, when asked once whether he feared giving his children unusual names might cause problems for them in later life, replied: “It’ll be their last name that gets them into trouble.”

For me, Frank Zappa was the most intimidating person I ever interviewed. But that was in 1984, long after his empire had been built, his rule established. I was there to talk to him – laughably, I now realise – about rock music, and Frank had never been interested in that. Pauline Butcher recalls: “He listened to the blues and classical. He did not play any rock’n’roll whatsoever – none. He loved Stravinsky, Varèse, Bartok… They were the main ones.”

“I think he was unusual probably from the time he was born,” said Gail in 2012, speaking on the phone from the kitchen of the house she and Frank lived in for nearly 25 years. “I think that he came pretty much full-blown the way that he was. I don’t think you can change yourself so radically. I think he just was a person who was very interested in freedom. He was a patriot and he was a composer. Just a strange combination.”

Certainly as a child he was different. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, four days before Christmas in 1940, Frank Vincent Zappa was the eldest of four kids to a French- Italian mother, Rose Marie, and a father, Francis Vincent Senior, a Sicilian immigrant of Italian, Greek and Arab ancestry. At home, Frank spoke mainly Italian, learned from his grandparents; at school he spoke Yankee-doodle-dandy.

His father was a mathematician and scientist working for the US defence industry, so the family moved around. This included a spell in Florida during Frank’s infant years, before settling back in Baltimore, where his father’s new job at the Edgewood Arsenal Chemical Warfare facility meant there were always gas masks around the place, waiting to be pulled on quickly in the event of ‘accidents’. Mention of germs and germ warfare would later infiltrate Frank’s music.

He was a sickly child, stricken by bouts of asthma and endless ear, nose and throat complaints. When the family doctor inserted pellets of radium into his nostrils to combat sinusitis, it so traumatised him that nostril references and nasal images would also surface regularly in his adult work.

When he was 12 the family left Baltimore for good, moving down to Southern California, where Frank senior’s work took him to posts in Monterey, Claremont and El Cajon, before finally settling in San Diego, where Frank junior attended Mission Bay High School – and where he joined his first band, The Black-Outs, as a drummer.

Pauline Butcher, who met Zappa in London in September 1967 before going to work for him, says she thinks “his thing” was affected by going to so many schools when he was young. “He ended up being with all the drop-outs and the people that weren’t popular at school. I think that stayed with him the rest of his life. He related to the underdog and the people who were outside the mainstream.”

A walking contradiction, he was a serious-minded teenager who composed his first orchestral work when he was 14, wrote precocious letters requesting meetings with his heroes Igor Stravinsky, who lived in California, and Edgard Varèse, who lived in New York. (Varèse agreed to a meeting, then cancelled.) Yet he spent most of his free time listening to doo-wop records and watching monster movies, cruising all night in a car with his only friend, another high-school outsider named Don Van Vliet, later renamed and mentored by Zappa as Captain Beefheart (something the Captain, himself a mass of weird contradictions, never quite forgave him for).

But if the teenage Zappa was nerdish and unpopular, what hardened and turned him into the unforgiving, controlling personality that characterised everything about his adult life was an incident that took place when he was 21. By then Zappa was the proud owner of a little five-track facility in Cucamonga, which he’d bought with the fee he’d received for scoring a B-movie cowboy flick called Run Home Slow. Thus, in a typically oddball way, began Zappa’s career as a composer and producer. Early success included a doo-wop number for The Penguins, titled Memories Of El Monte (for which he’d received 75 cents), and Grunion Run, the B-side of a novelty single called Tijuana Surf which went to No.1 in Mexico.

He was awaiting royalties for that when, in 1962, a middle-aged man offered to pay him $100 to make a “party tape for the guys” – early-60s code for a porn tape. Hardly high art, but 100 bucks would go some way to financing his next dreamed-of project, a movie he’d written called Captain Beefheart Vs. The Grunt People. So the following evening, Frank and a girlfriend recorded themselves bouncing around on a squeaky mattress, making “Ooh’ and “Aah” sounds and trying not to laugh. There was nothing funny, though, when the middle-aged ‘John’ turned out to be one Detective Willis, and Zappa was sentenced to six months in jail for peddling pornography.

He eventually served only 11 days in jail, with the remainder reduced to probation, but it gave him enough of a criminal record to not be eligible to be drafted to Vietnam. The rest was all downhill, according to those that knew him. He was left with a permanent sense of injustice. Worse, he was left with a morbid fear of the police, a condition that led both to his outlawing of drug use in his presence, and his bitter mistrust of authority figures and institutions.

“He was so terrified of being arrested,” says Butcher. “If the police had come and found drugs in the house, then he would have been thrown into jail as well and he couldn’t have gone through another experience like that. It’s never been totally explained what happened to him there, but there are some implications that he was sexually abused – because he had long hair.”

By the mid-60s, at a time when the clean-cut Beatles were still regarded as a threat to the nation’s youth, Zappa was every straight-thinking Middle- American’s nightmare writ large: long hair, Zapata moustache, thrift-store clothes and an apparent dislike of hot baths of cold showers. But he knew his days of being the “lone freak”, as he later put it, of the small town he lived in were numbered. He just needed a vehicle to transport him to the next level.

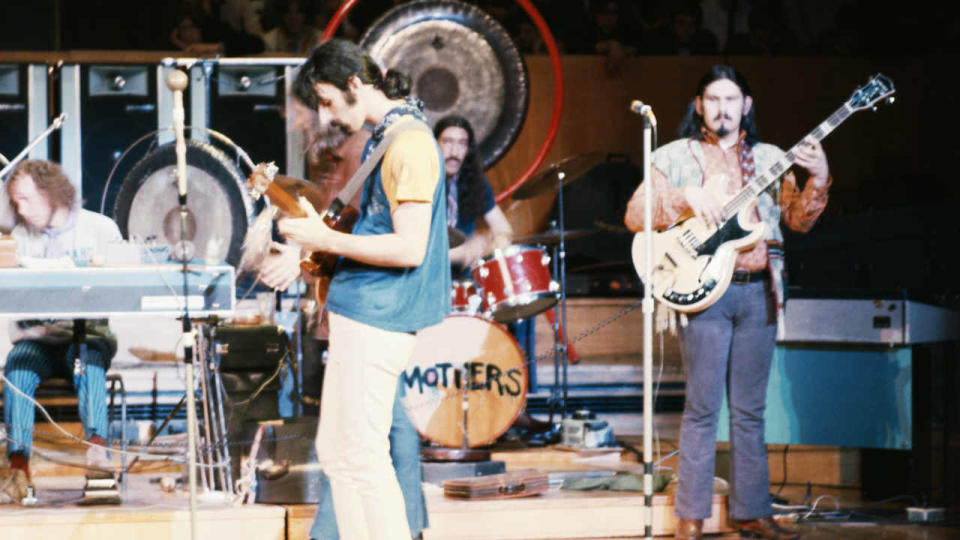

No man is an island – not even Frank Zappa. And he would need the help of other like-minded solitaries to help free him up to do what he wanted to do. Enter the most talented, misunderstood, repulsively attired yet aptly named group in the rock’n’roll pantheon: the Mothers Of Invention. Betraying some of the bitterness that would understandably come to characterise many of the former Mothers’ memories of their association with Zappa, their original bassist, Roy Estrada, once put it: “Frank joined us, we didn’t join him.”

That is true – but only to a point. They were known as the Soul Giants when Zappa joined as guitarist in 1965, along with vocalist Ray Collins – Zappa had released a couple of his songs under monikers like The Heartbreakers and Baby Ray & The Ferns. They were a talented but unadventurous weekend bar band playing covers at a club called The Broadside in the downtrodden Los Angeles suburb of Inglewood. Zappa, the Sagittarian fire sign with a brain like a planet, was about the change all that.

“I suggested we develop our own stuff and try to get a record contract,” Zappa later recalled. “The leader at that time, a guy called Davey Coronado, said: ‘No way. Because if you learn original stuff, the bars won’t hire you.’ So he quit. And he was right. We stayed together, changed our name to the Mothers, and we did get fired.”

No band was ever gonna be big enough for Frank Zappa to share leadership in. Fortunately, the mid-60s was a fast-paced musical melting pot where the music business was already midway through its transformation from single-oriented pop to album-oriented rock. When Tom Wilson – producer of Bob Dylan’s earliest albums and original musical mentor to the Velvet Underground – caught an early Mothers Of Invention gig on Sunset Strip, he thought he saw a progressive rock and blues outfit not unlike The Doors and Love, then also making baby steps into the scene. Signing the Mothers to the MGM-Verve label, he had no idea what he was in for once Zappa got the band inside a proper recording studio.

Despite being briefly considered as a producer for The Doors, Zappa viewed fellow Angelino acts like The Doors and Love as glorified hippies, which he considered “a very conformist group, with an established uniform, vocabulary and lifestyle”. The Mothers were something else: they were freaks. Hence the title of their first album: Freak Out!

A double album released at a time (June 1966) when single albums were still mainly comprised of hits and filler, Freak Out! was an anomaly on every level, even in a year that saw the release of game-changers like the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and The Beatles’ Revolver. From its inner gatefold sleeve comprising various boxes of thank-yous and credits – including names like Carl Franzoni (aka Captain Fuck, self-styled leader of the LA freak scene), Suzy Creamcheese (a fictional catch-all groupie that would crop up on several subsequent Mothers albums), Kim Fowley (‘on hypophone’), even ex-wife Kay (credited for inspiring Anyway The Wind Blows) – Freak Out! seemed built to confuse all but the already – metaphorically, at least – freaked out.

Tom Wilson was credited with production, but soon handed over control – as everyone finally did – to Zappa. Wilson got a good inkling of what he was in for after Eric Burdon, who Wilson had hired Zappa to produce a couple of tracks for, described the experience as “like working with Hitler”. When Zappa hit the producer up for $500 to bring in as many freaks as he could find from the Strip to record the free-form musical malaise that comprised side four, The Return Of The Son Of Monster Magnet (described by Zappa on the sleeve as Unfinished Ballet In Two Tableaux, the first titled Ritual Dance Of The Child Killer), Wilson simply paid up. Life was too short for this kind of shit.

Not unexpectedly, Freak Out! was not a hit. Yet its message outstripped sales to such a degree that the names Frank Zappa and the Mothers Of Invention became synonymous throughout the album-buying world with a musical mien that belonged not to the narrow enthusiasms of the chart?buying public, but to the new rock cognoscenti; the ones who listened not just to Jimi Hendrix and The Doors but also to John Coltrane and John Cage, maybe Bartok and Stockhausen too.

As Melody Maker noted in its belated review of Freak Out!, published in March 1967: ‘Throwing off their social chains, freeing themselves from their national social slavery and realising whatever potential they possess for free expression the Mothers Of Invention toss the moral code aside like spare sugar lumps. That is, they’re sending up American society, advocating free love, nay, advocating freedom already.’

Sales of the album may not have jumped significantly as a result, but word of mouth spread like wildfire, and six months later the Mothers were headlining London’s Royal Albert Hall.

The true musical identity of the Mothers, though, was not really established until their second album, Absolutely Free – the first to feature keyboard player Don Preston and sax player Bunk Gardner. “Frank and I both had the same record collection,” Preston remembers now, from his Hollywood home. “But I’d already been playing outside music for a few years. We didn’t play jazz or classical, we improvised to unusual things.”

The most unusual being the bicycle which Preston (who also claims to have invented the Moog synthesiser) “taught Frank to play”. Joining Zappa, whom he’d known since the early 60s, Preston was a natural fit. “I was just overjoyed to be able to do that kind of material and have an audience listen to it, instead of just doing it in my garage,” he says. At that point, Preston recalls, there was little separation between band and band leader. “He was a lot of fun to be around and hang out with,” he says now.

Recorded in just four days in November 1966 and released four months later in March 1967, and billed as the first and second in A Series Of Underground Oratorios (side one and side two to you and me), Absolutely Free set the template for everything Zappa would record during what is now regarded as the classic Mothers period, from 1966 to 1970. Seemingly free-form jazz-influenced rock – although actually minutely annotated neoclassical music using mainly electric instruments – was interwoven with extracts of off-the-wall taped conversations, lewd commentary, and a sense of the absurd that bordered on sinister.

The Mothers’ musical ethos was best embodied on Zappa’s first real masterpiece, on side two, Brown Shoes Don’t Make It. Ostensibly a blues-acid-rock-pantomime-groove-laden satire on suburban America, with Captain Beefheart growling in the background, it switches suddenly into a third-person narrative about a sleazy government official fantasising about screwing a 13-year-old girl, ‘rocking and rolling and acting obscene’. None of which really conveys the dizzy sense of watching a theatrical production crumble before your eyes, revealing only the actors, naked, learning their lines. And failing.

For the first six months after Preston and Gardner joined, the band rehearsed for eight hours a day, seven days a week. There were strict rules: if you were sick, you could be asked for a doctor’s note or lose a day’s pay. Preston describes the band as “democratic”, although it was always clear who was in charge.

Zappa had already begun staying at a different hotel from the rest of the band. Drummer-cum trumpeter Jimmy Carl Black later recalled: “The Mothers were into sex, drugs – not heavy drugs – and rock’n’roll.”

Zappa, by contrast, was only into one of those things. He had been curious enough to watch while Ray Collins dropped acid, and not impressed enough to try it himself. Zappa’s only known drug foray, smoking 10 joints in one sitting, just left him with a sore throat, he said. And he certainly didn’t like rock’n’roll.

But when it came to sex, and taking advantage of the newly announced ‘permissive society’, Frank was right there at the cutting edge. He’d already been married (to his teenage sweetheart Kay Sherman) and divorced before the Mothers. Now he revelled in those aspects of the freak scene that included groupies, fuck buddies and one-night stands. Even when he was shacked up with Pamela Zarubica, it wasn’t unusual for her to come home and find Frank in bed with different girls. Because of their open relationship, outbreaks of crabs were common, as was getting the clap. Indeed crabs would later inspire several Zappa classics, such as Toads Of The Short Forest.

His second wife, Gail – who had spent her formative years in London, as part of the same social scene as The Beatles and the Stones – had also for a short time been a groupie. “And an excellent groupie too,” Frank boasted in interviews. “It didn’t matter to me that she had slept around with other beat men.”

Yet Pauline Butcher says he had a more traditional outlook on marriage. “He didn’t think the marriage would last if Gail had outside sexual partners. He had outside women, but not to the extent that he would leave Gail or break up his family.”

Gail, a blonde-haired beauty, had met Frank in early 1966. He had the clap and crabs, the latter venturing as far north as his hair. She married him a year later, on the heels of his first European tour. Speaking to Classic Rock in 2012, she described Frank as “incredibly stable” at home. “But of course, all that changes when he’s on the road and, from a wife’s point of view or from a girlfriend’s point of view, you have all the occupational hazards that rock’n’roll can present to you. All I can say is that the secret to not killing yourself over stuff like that is you stay focused on what it is that you want for yourself in your life.”

Zappa sang about sex endlessly, in every permutation and situation he could conceive of. Sometimes it was puerile (Penis Dimension), sometimes it was profound (America Drinks And Goes Home), but it was always there somewhere. Proto-feminism at play, perhaps? Or just a more clever form of male chauvinist pigdom? When Zappa told Rolling Stone he found the work of knob-modelling groupies Cynthia and Dianne Plaster Caster “artistically and sociologically… really heavy”, no one knew if he was joking. Later he hired Cynthia to become a full-time babysitter for Gail, a role she proved very good at.

Meanwhile, back at the coal face, the divide between the Mothers and their leader grew even wider when Verve failed to pick up the option for the band’s next album, and Zappa’s street-smart manager, Herb Cohen, used the loophole to negotiate a much better deal for Zappa that included the formation of his own production company, through which he would control the release not just of all future Mothers Of Invention albums but also his own solo projects and those of any other artists he chose to sponsor. Those who were there say that this marked a key staging point in Zappa’s transformation from band leader to group dictator.

“Zappa was always the leader, but we all had equal responsibilities,” says Don Preston. “By the time we reached the Log Cabin, Zappa was the main guy; he was the man. It felt more isolated.”

The shift became complete with the release of Zappa’s first solo album, Lumpy Gravy, released in August 1967, just five months after Absolutely Free. At this point things got really complicated. And they stayed that way for the rest of his life.

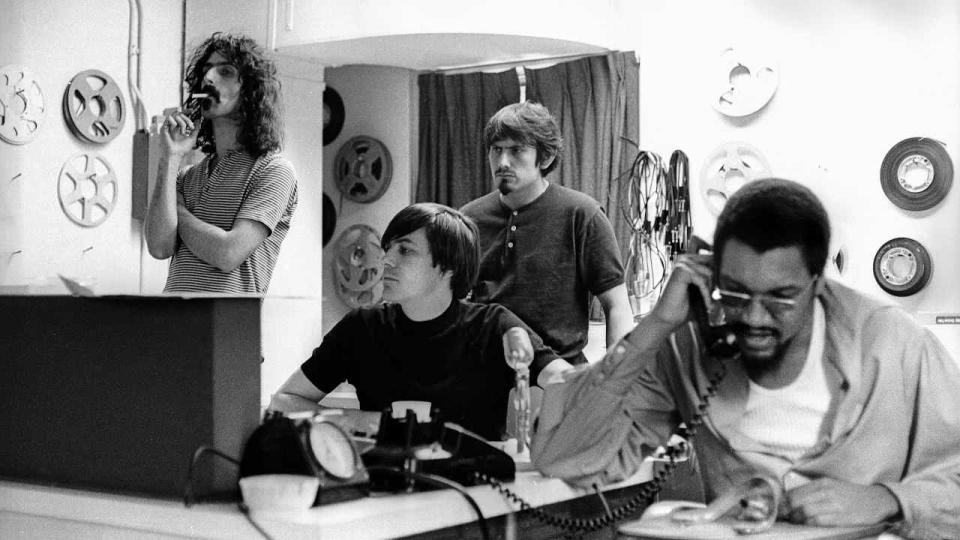

Put as simply as possibly, Lumpy Gravy went from being an orchestral work performed by a group of session players he named the Abnuceals Emuukha Electric Symphony Orchestra, to a drastically re-edited strand in a larger production called No Commercial Potential, which itself comprised a further two albums, both credited to Frank and the Mothers: We’re Only In It For The Money (released in March 1968) and Cruising With Ruben And The Jets (December 1968).

While none of the albums sounded remotely like the others, according to Zappa it was all one album. He claimed that he could cut the master tapes into different running orders and it would still make sense. It was, he explained, part of his “project/object” concept: each album was a different ‘project’ but all the albums combining to make a bigger ‘object’.

While one of the ‘related’ albums – Cruising With Ruben And The Jets, a set of doo-wop songs corralled into a ‘concept’ album about a fictitious group called Ruben & The Jets – baffled critics to the point of irritation, the other two remain among the finest works to bear either the Zappa or Mothers imprimaturs. Indeed Lumpy Gravy remained one of Zappa’s personal favourites. Working around the clock in the studio with a full orchestra at his disposal and state-of-the-art 12-track recording facilities, Zappa was in his control-freak element. “He drove everyone crazy,” says Preston, “making us do 28 takes of the simplest little bridge.”

But it was the next Mothers album, We’re Only In It For The Money, that really sealed the deal here in the UK. An alternative-universe take on The Beatles’ Sgt Pepper, complete with hilariously mocking sleeve and a cameo from a stuttering Eric Clapton, it was one of the most incisive and unforgiving satires on the whole so-called 60s ‘movement’.

“Everybody else thought they were God!” Zappa said of The Beatles. “I think that was not correct. They were just a good commercial group.” Perverse to the last, he let it be known he preferred The Monkees.

By now Zappa was living in a small, third-floor apartment in New York with his new wife, Gail, then pregnant with their first child. It was at this point that drummer Arthur Dyer Tripp III joined the Mothers. Tripp had performed solo concerts of the works of John Cage and Stockhausen – heavyweight stuff, considering the height of drummer-related sophistication had entailed Ringo Starr singing _Yellow _Submarine. Tripp had just finished a two-year stint playing with the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra and he was ready for anything.

“Frank was continuously on the prowl for new ideas and inspirations,” Tripp says, speaking from his home in Mississippi, “so just about anything we discussed was used. To be associated with a guy who basically favoured ‘anything goes’, but at a high level, was heaven for me. I shared Frank’s counter-culture, anti-mainstream philosophy, and in those days we made fun of everything.”

Tripp recalls Zappa being ill at ease in social situations. “He tended to feel comfortable only when he was in control of the subject matter, and its direction,” says the drummer.

It was a world away from how Zappa was seen by his fans. When Jimi Hendrix dropped by the New York apartment to say hi, instead of the “crazy scene” he had envisaged, he found Gail and Frank making supper. That didn’t stop him getting up and jamming with the Mothers on stage that night, though Zappa left him to it, sitting in the stalls to watch Jimi play. It was also in New York that he appeared in an episode of The Monkees, playing Mike Nesmith, while Nesmith, dressed as Zappa, played him. (He was also in The Monkees’ movie Head, playing Davy Jones’s mentor, while leading a talking bull.)

“He was a precociously intelligent man in a business which is not necessarily filled with a lot of intelligent people, and he stood out,” observes Pauline Butcher. “He worked out he wasn’t a pretty boy like The Beatles and the Rolling Stones, he didn’t play their kind of music, he didn’t even like it, and if he was going to get himself heard he was going to have to do something radically different. He went out of his way to have outrageous photographs taken: the one on the toilet, the one with his pigtails sticking out like a spaniel, dressing up in women’s clothes. All these things were calculated because he had to get himself attention.”

By the time the extended Zappa family had moved back to Los Angeles in 1968, being radically different was hardly a stretch. He and Gail rented a log cabin in Laurel Canyon once owned by 20s cowboy movie star Tom Mix for $700 a month. Frank dubbed it “Freak Central”. The Canyon had been transformed from a rundown, overgrown semi-wilderness by musicians looking for cheap places to hang out and get high, to play their music beneath the bird-of-paradise plants, thickets of pepper trees and pines.

It was here that the Zappa mythology that had begun to build in New York now rose to a whole new, stupendously far-out level. Visitations by rock royalty were daily occurrences. Mick Jagger and Marianne Faithfull turned up, followed later the same night by members of The Who, followed even later by Captain Beefheart, aka Zappa’s old school friend Don Van Vliet. They finished the evening jamming in the basement on Be Bop A Lula. (Beefheart complained that Jagger gave him a dud mic to prevent him being overpowered vocally.) Eric Clapton stopped by the next night, but Frank was unimpressed, complaining that “he wasn’t the jamming type”.

Jefferson Airplane singer Grace Slick was another visitor. In her autobiography, she describes the Log Cabin as ‘like a troll’s kingdom. Fuzzy-haired women lounged in long antique dresses, and naked children ran to and fro while Frank sat behind piles of electronic equipment discussing his latest ideas for orchestrating satirical hippy rock music – openly [making] fun of the very counter-culture he was helping to sustain.’

Then there were the wannabes and hopefuls. When Larry Fischer, a 24-year-old escaped mental patient, jailed at 16 for trying to knife his mother, turned up to sing Frank a song, Zappa signed him to his new Bizarre label and recorded a double album with him, An Evening With Wild Man Fischer. Zappa continued to mentor Fischer (described as “something not entirely musical”) – until he threw a glass jar at Moon, at which point Gail put her foot down and Fischer was permanently ejected. A more successful newcomer Zappa signed to Bizarre was the Alice Cooper Band, a group of reprobates who dressed in women’s clothing and sang songs called Earwigs To Eternity and B.B. On Mars.

“I’d seen Zappa play at Thee Experience club in LA,” Alice recalls now. “One night it was Eric Clapton, Mike Bloomfield, Jimi Hendrix, all jamming. Then Frank gets up and does an imitation of each one of them! Then he takes off and starts playing his own riffs, and those other guys just stood there, like, ‘What?!’ Cos this guy was doing stuff that they had never seen before. Even Jimi Hendrix. Frank gave Hendrix his first wah-wah pedal and showed him what it was.”

When one of the Log Cabin regulars told Frank of this band that every record label in LA had turned down, he asked to see them. The following morning, at seven o’clock, they were on his front lawn, bashing out their strangely unlovely set.

“We got our times wrong. We’d heard he wanted us there at seven, we figured he meant seven in the morning,” says Alice. “But we played five songs that were two minutes long and had, like, 25 changes in them, and he sat there and he listened. Then he looked at me and said: ‘I don’t get it. I don’t get what you just did.’ And then we played another one for him that did the same thing. And then another, and another. They were like if you took an ELP prog piece and condensed it to two minutes. And he just kept going: ‘I… don’t… get… this!’ I said: ‘Is that bad?’ He said: ‘No. The fact I don’t get it is why I’m signing you.’”

Arguably the most infamous of all were The GTOs, the group of teenage groupies that Zappa took under his wing. They originally called themselves the Laurel Canyon Ballet Company, until the night they turned up at the Cabin naked except for bibs and giant nappies, their hair up in pigtails and all sucking lollipops. A delighted Frank insisted they dance on stage with the Mothers that night. And that they change their name to The GTOs.

GTO stood for many things: Girls Together Outrageously, Girls Together Only, Girls Together Occasionally, Girls Together Often, and any number of similar acronyms. “The GTOs would get dressed up every night to go dancing, cos there was safety in numbers,” said Gail Zappa in 2012. “They wore these wild outfits [and], they would also get in the Whisky free so they could dance. Cos for a while they were the entertainment.”

In the GTOs there was Miss Cinderella, Miss Christine, Miss Pamela, Miss Mercy and Miss Lucy (plus, at different intervals, Miss Sandra and/or Sparky). Having proved themselves by appearing on stage at several Mothers Of Invention shows as dancers and/or backing vocalists, in November 1968 Zappa put them on a weekly retainer of $35 each. “People just got off on them,” recalls Alice Cooper. “They were a trip.”

When Zappa produced their sole album, Permanent Damage, in 1969, he got Rod Stewart to sing on the track The Ghost Chained To The Past, Present, And Future (Shock Treatment). Jeff Beck and Nicky Hopkins also appeared on the record, conducted by Frank.

And did Zappa enjoy any extra ‘perks’ from the job? Pauline Butcher is emphatic that he did not. “He wasn’t interested in The GTOs on a groupie level,” she says. “He wasn’t a sexual predator at all. He didn’t lunge after anyone. He didn’t come across as a dirty old man-type of thing. He was not like that. He was far too laid-back.”

Why should he, when he and the Mothers were thronged by groupies at every gig they played? Again, Butcher is defensive on the subject. “He only had these women on the road because he was highly sexually charged, I suppose, and he just needed an outlet for his sex.” But the fact is, Zappa wrote more songs about groupies and sex in general – including taped conversations with groupies discussing their various conquests – than any other artist before or since.

One time when Zappa went back to play in London, Pauline, who had stayed behind in LA, got tickets for the show for a friend of hers. “She went to the club afterwards where he was,” she recalls. “And Frank said to her: ‘I’m looking for a fuck. Are you available?’ She said: ‘No, I’m married.’ He said: ‘Well, does that make any difference?’ He would get very grumpy if he didn’t get any groupies. And then Gail would have to fly out and sort him out.”

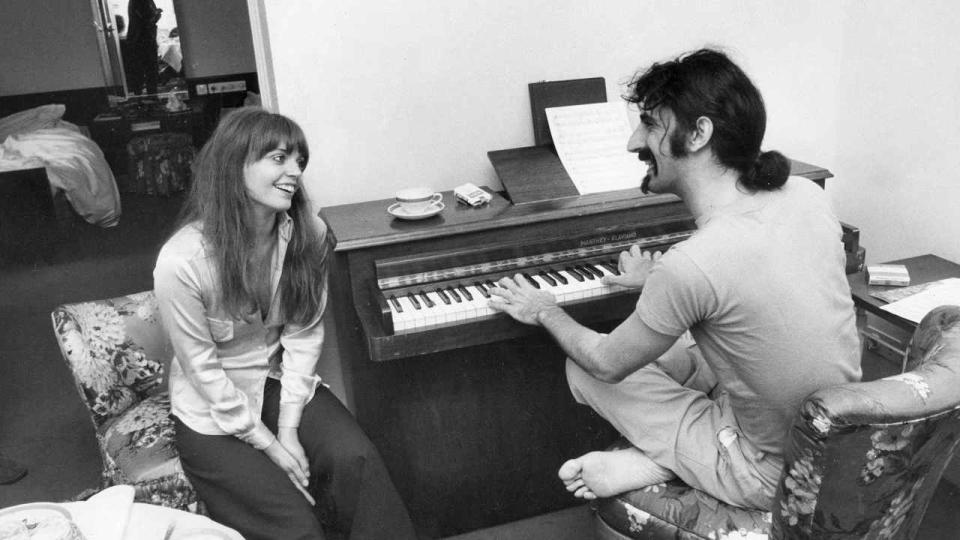

Nevertheless, both Gail Zappa and Pauline Butcher insist he was a different man at home. When it came to personal and professional relationships with women, Zappa could be nurturing, inspiring even.

“The main thing was, he listened to what I had to say,” says Butcher. “This, in 1967, ’68, was revolutionary to me. It was just so unusual for me, [for him] to listen and take seriously what a woman had to say. He treated me like an equal. Which was extraordinary.”

If so, she was the exception. From here on in, Zappa rarely, if ever, treated anyone like an equal. By the time he came to record what was officially his second solo album, Hot Rats, in the summer of 1969, the transformation was complete. Frank Zappa was the Mothers, and the Mothers were whatever Frank Zappa wanted them to be. In this case, that meant a collection of jazz-leaning orchestral rock with an extra twist of post-psychedelic savagery.

Opening track Peaches En Regalia, despite its compositionally complex parameters, would become the most instantly recognisable Zappa track of his career – the All Right Now of the freak generation. Willie The Pimp featured typical Zappa outsiders such as Captain Beefheart on vocals and Don ‘Sugarcane’ Harris – recently bailed by Zappa from jail after his latest drug bust – on violin. Willie would also become – an unlikely term in this context, but nonetheless true – a real crowd pleaser. Violinist Jean Luc Ponty plays on It Must Be A Camel, and a young, uncredited Lowell George also features.

Although the album didn’t even break the US Top 100, it became Zappa’s only Top 10 hit in the UK and would go on to become one of his biggest-selling album worldwide. Not that Frank gave a shit. Or at least he said he didn’t. Within weeks of its release, he had officially broken the Mothers up.

Pauline Butcher says that the first night she arrived at the Log Cabin, in May 1968, “he told me that he wanted to break up the Mothers. All the way through the band, he said this. There was another crisis about a month later, and he was gonna break up the band then. And then Ian Underwood said he would rehearse the band, and that started the lifelong habit of Frank always having someone else in the band rehearse the band, and learn the parts before he joined them, because he hadn’t got the patience.”

Zappa himself put it more bluntly: “How long can you be enthusiastic about music as an art form, never mind music as a business, when it involves other people that you have to rely on, and they piss on your shoe?” he said. “Why do you have to put up with that? The more I can rely on myself, the better I like it.”

Whatever one’s views on Frank Zappa – his music, his personal politics, his attitude to women and fellow band members – by the end of the 1960s he had become as significant a figure in rock culture as almost anyone else one might wish to make similar claims for. He would re-form the Mothers Of Invention in the summer of 1970, when the expediency of filling venues on a lengthy tour demanded. He would even record more music with them. But as Don Preston says: “By then we were just hired musicians.” And he made a film featuring some of them: 200 Motels; as dreary, incoherent and interminably tedious as any of the other truly awful ‘wacky’ movies of the period – only more so.

Mostly, though, Frank Zappa would go on to become… Frank Zappa. Which meant many, many more great albums – though none, it has to be said, ever quite so daring, seemingly impromptu and alive with the gung-ho spirit of the times as the ones he made with The Mothers Of Invention.

In 1969, the Zappas finally moved out of the Log Cabin and into a more conventional home, still in Laurel Canyon but this time with doors that had locks. They would live there together for the rest of Frank’s life. On the door leading to the basement where he worked was a sign: ‘Dr Zircon’s Secret Lab In Happy Valley’. What came out of that lab over the next near quarter of a century will likely be argued over for centuries to come. There were 62 albums – live, studio, rock, jazz, orchestral, singles, doubles, trebles – released during his lifetime, a further 35 original works released posthumously, plus 13 compilations and box sets at last count, and god knows how many bootlegs.

“He was driven by the stimuli around him,” said Gail Zappa in 2012. “Everybody else, if you were in a rock’n’roll band you were typically sitting around getting stoned and bumping into each other while you write their songs. Frank was clearly a band leader and didn’t tolerate that kind of behaviour in a working environment. So I don’t think he was suffering in any major way, other than not being able to get any exposure on the radio or television or anything like that.”

She added Frank once complained of a boring life, because all he did was work. “He just wrote dots on paper, but he used to talk about connecting the dots – which really speaks to what he did in terms of music and what he did in terms of social commentary.” You know what she means, even if you don’t. Just like her husband’s music.

The term ‘musical genius’ is so overused as to be obsolete. Yet it’s difficult not to draw on it when it comes to the story of Frank Zappa.

“I would say yes, he was – as long as you put the word ‘musical’ there,” says Don Preston. “If he was a genius he’d still have the first band together and we’d all have been making millions of dollars, like the Grateful Dead. But a musical genius? Yes, absolutely.”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #178.