The Pete Townshend song that savaged a pair of music writers

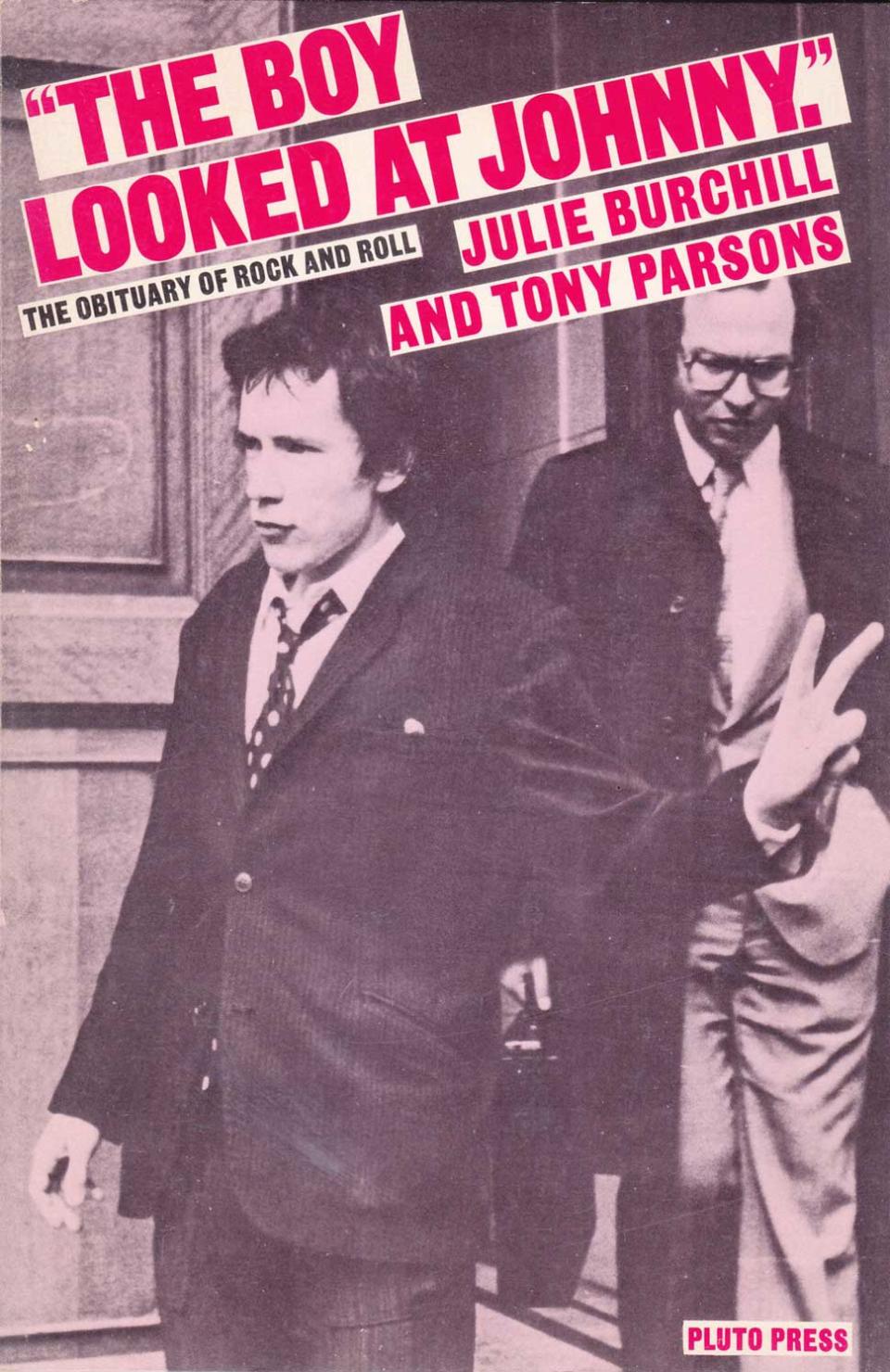

There are plenty of books by embittered old rock stars and sorry has-beens. But in an industry where backbiting and cheap shots are a pitiful, if entertaining, by-product of lost opportunity and thwarted ambition, few books are quite so scathing as The Boy Looked At Johnny, written by NME journalists Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons.

Published in 1978 and subtitled The Obituary Of Rock And Roll, the book is a venomous rant against the failed promise of punk. Its 79 pages poured bile on almost anyone and anything that dared crawl from CBGB, the 100 Club or The Roxy. The young authors said The Clash’s Mick Jones merely “chanted stray battle-cries like a harassed housewife”, and the Sex Pistols-affiliated Bromley contingent were just “a posse of unrepentant poseurs” committed to attaining fame despite their paucity of talent.

American bands fared little better. It was an unremitting stream of invective, marked by its no-prisoners approach, stray humour and the odd moment of sheer madness (Tom Robinson, they concluded, was the saviour of rock’n’roll).

Enter Pete Townshend, captain of The Who and one of the old guard that punk was supposedly meant to sweep away. The end of the 70s found Townshend in a crisis of sorts. Friend and bandmate Keith Moon was dead at 32, his marriage was collapsing and he had become addicted to heroin and booze. The great idealist and unwitting spokesman of 60s pop was suddenly unsure of his place in the future. All of this fed directly into Empty Glass, the solo album he’d been readying for 18 months.

“I was on an all-time personal high,” Townshend says today. “But I was drinking a lot and my marriage was in difficulty because I was doing Who work and solo work at the same time.”

The death of Moon was still raw in Townshend’s mind. Shortly after, he read a newspaper interview in which Burchill and Parsons were promoting The Boy Looked At Johnny. In it, the subject of Moon came up.

“Tony brought up Keith and said: ‘Fuck Keith Moon, we’re better off without him. Decadent cunt driving Rolls-Royces into swimming pools. If that’s what rock and roll’s about, who needs it?’” Townshend told the NME in April 1980. “And to a certain extent I agreed with a bit of it. But I feel that it was a bit of opportunist cock.”

The experience jolted Townshend into writing Jools And Tone, a caustic response to the glib arrogance of Moon’s accusers and, by association, the wider rock press. The title was soon amended to the more punningly Truffaut Jools And Jim. The lyrics were almost relentlessly toxic, veering from outrage to outright scorn: ‘Did you read the stuff that Julie said?/Or little Jimmy with his hair dyed red?/They don’t give a shit Keith Moon is dead/Is that exactly what I thought I read?’

Over a near-frantic beat and needling guitar, Townshend dismisses the young NME upstarts and their ilk as little more than ‘Typewriter bangers, you’re all just hangers on/Everyone’s human ’cept Jools and Jim/Late copy churners, rock and roll learners/ Your hearts are melting in pools of gin.’

But had Keith Moon’s death triggered Townshend’s own problems? “Yes. But I was angry, not depressed,” he explains today. “I was angry with Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons for saying in their book that it was a good thing Keith Moon was dead. But I got a good song out of it. I have to be quick to say that of course I realised in hindsight that I had problems, but at the time I really enjoyed the chaos I was creating.”

In fact, as he explained to Charles Shaar Murray on the eve of Empty Glass’s release, Townshend “just wrote the song as a reaction. I rang Tony up the day after I’d written it and explained. I was going to send him a copy, and then I decided I wouldn’t until it came out, after I’d decided that it was a good song to go on the album.”

Empty Glass itself isn’t the work of some old stager making a defiant stand for either an earlier generation or the music that defined it. Townshend appreciated what punk stood for; it reminded him of the early days of The Who, working- class bandits tearing up the old scene, but he also understood that, as part of the established rock hierarchy that punk was meant to destroy, he was now part of the problem.

In Rolling Stone Townshend wrote of his punky dilemma: “I’m sure I invented it, and yet it’s left me behind… I am with them. I want nothing more than to go with them to their desperate hell, because that loneliness they suffer is soon to be over.”

Around the same time, he launched a drunken tirade at the Pistols’ Steve Jones and Paul Cook. “Rock’n’roll’s going down the fucking pan!” Townshend screamed. “You’ve got to take over where The Who left off!” The two Pistols merely stared back and fretted about The Who, their favourite band, splitting up.

Townshend’s predicament was detailed in one of the final verses of his song Jools And Jim. The music suddenly adopts a softer tone, his falsetto voice now more self-reflective and conciliatory: ‘I know for sure that if we met up eye to eye/A little wine would bring us closer, you and I/‘Cos you’re right, hypocrisy will be the death of me.’

Rather than an indignant rant, the song is ultimately a sympathetic one. Townshend later admitted to admiring The Boy Looked At Johnny, taking the book’s message as both a personal challenge and a comment on hypocrisy. He remains forever wary of the music press, though.

“Many of my harshest critics are wonderful writers themselves,” Townshend says today, “but many of them really do think they can read the inside from looking at the outside. The difference between an artist and a journalist is that an artist deals in truth, and journalists deal in facts and opinions. Analysis is something I’m delighted to do after the record is long finished.”

Jools And Jim was eventually issued as the B-side of Keep On Working in 1980. The fallout from Julie Burchill and Tony Parsons’s book The Boy Looked At Johnny fed into Townshend’s ambitious 1993 project Psychoderelict. One of its less likeable protagonists, a rock gossip columnist and scandal-monger called Ruth Streeting, is clearly modelled on Burchill.

This feature was first published in Classic Rock issue 173, published in Summer 2012.