Peter Frampton looks back over an extraordinary six-decade career

In September 2022, Peter Frampton appeared on the cover of Classic Rock as his career drew to a close. But it didn't quite work out like that. The farewell tour he was about to embark on – prompted by a battle with the degenerative disorder IBM – was extended, and he's just finished another run of US dates. And later this year, he'll be inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall Of Fame. The interview that follows was our cover story.

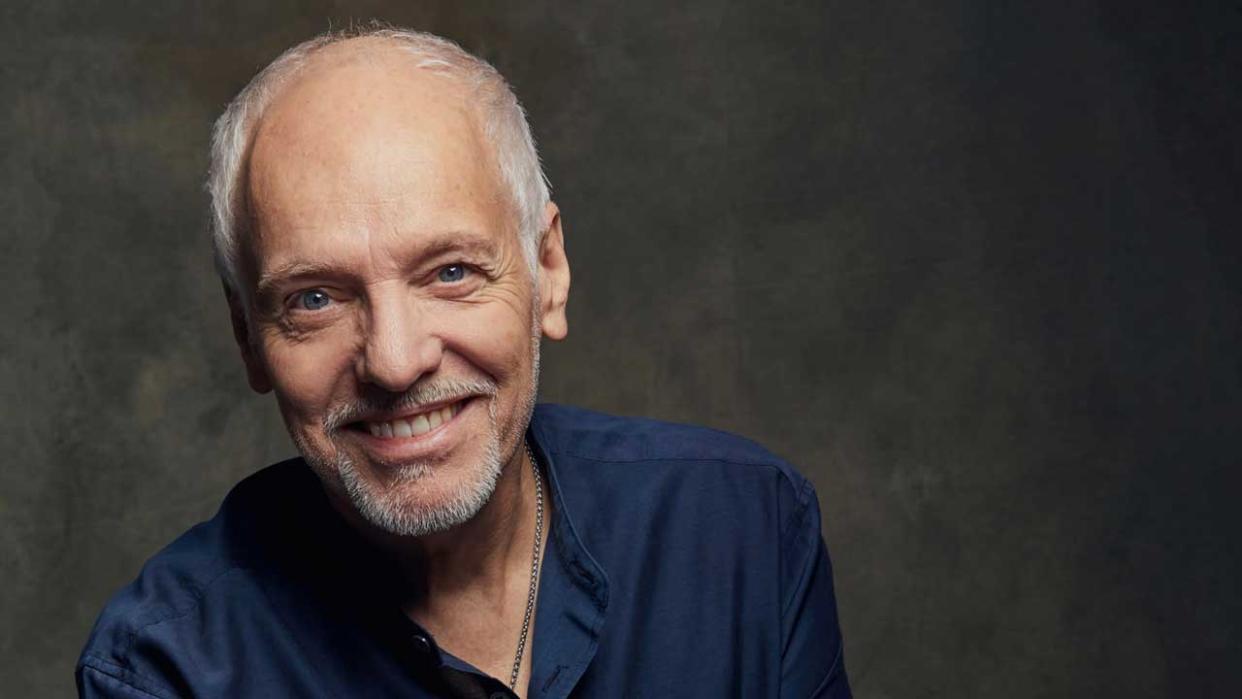

"Sorry, I know this is not quite what we had planned,” Peter Frampton says, aplogetically. For Classic Rock’s cover-story interview, we were set to meet the 72-year old at his recording studio in Berryhill, a hip neighborhood that has become Nashville’s new Music Row. But the night before, one of his studio assistants tested positive for covid. Foremost on Frampton’s mind was the safety of his two-year-old granddaughter Elle, who, with his daughter and son-in-law, was staying with him for the month. To err on the side of caution – and to be able to see each other’s maskless faces – we moved our chat to Zoom.

So here’s Frampton, at home on a humid July morning, dressed in a black T-shirt with a silver chain and polished metal-and-wood pendant, his closecropped hair and moustache-andbeard age-appropriately and unapologetically white. During our three-hour conversation, he’s funny and personable, quick to laugh at both himself and the head-spinning twists and turns his life and career have taken in his storied 56-year ride.

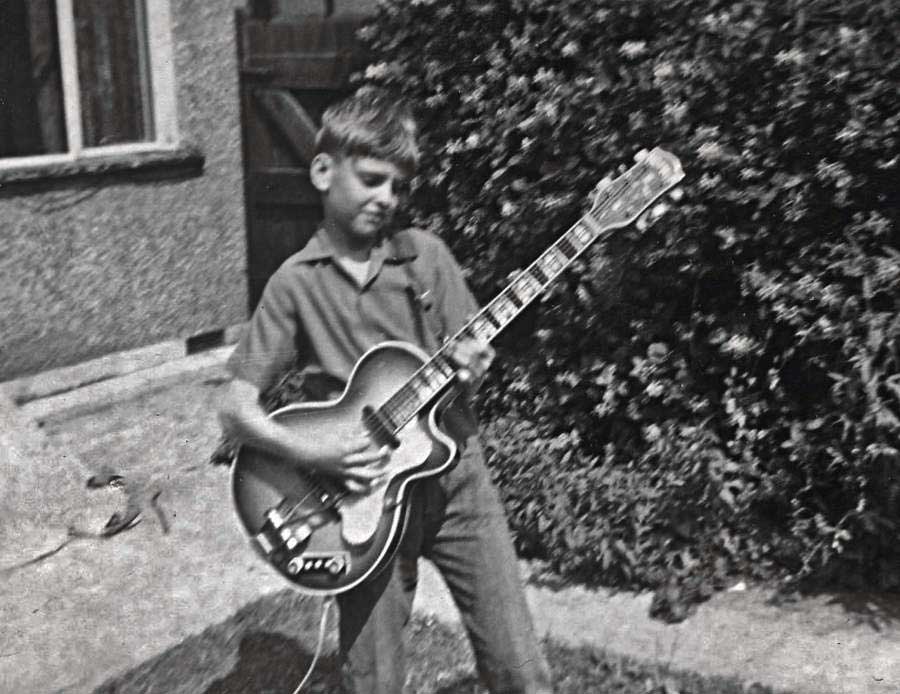

A little history: born on April 22, 1950 in Beckenham, Kent, Peter Kenneth Frampton was one of two children raised by educator parents. His dad Owen was an art teacher, who counted among his students the young David Jones, later Bowie. Peter was something of a prodigy, teaching himself guitar at eight and playing his first professional gigs at 13. By the time he was 16 he was performing on Top Of The Pops fronting pop group The Herd. He never looked back.

There were many ups and downs ahead. In our time together, we touched on them all: Humble Pie and Steve Marriott; sessions with George Harrison; nearly becoming a Rolling Stone; a Mob-connected manager; the Sgt. Pepper film debacle; touring as David Bowie’s guitarist; winning a Grammy; helping to make the film Almost Famous; the ill-fated Humble Pie reunion; being animated in The Simpsons; and of course Frampton Comes Alive!, the iconic emblem of 70s rock, and for many years the biggest-selling record of all time.

Before we get into your amazing career, I want to talk about your dad. He was an art teacher at Bromley Technical School, and one of his students was David Jones, who was one of your schoolmates. Did the young future David Bowie inspire you to pursue music?

Seeing David play with his band The Kon-Rads made a huge impression on me. There he was with his suit and his hair sticking up, playing sax and singing Little Richard songs. I thought: “I want to be him!” But I had already started playing a few years before. I picked up the banjolele first, then got a guitar for Christmas when I was eight.

I was one of those kids who learned everything really quickly. My parents’ eyes were popping out of their heads: “Oh my god, where did you learn that?!” “I heard it on the radio…” “But how?” “I don’t know, I just found the chords and sang along.” So I knew – and unfortunately they knew [laughs] – that the future was probably going to lead to me being a musician.

Didn’t you and Bowie play guitars together at school?

Yes. George Underwood and David were students of my dad’s. George is still one of my closest friends. So it was the three of us and we were all into music heavily. George was the first one on TV, as Calvin James, produced by Mickie Most. Then he decided that wasn’t for him and went into fine arts. And of course he designed the covers for [Bowie’s albums] Hunky Dory and Ziggy Stardust.

My dad said: “Why don’t you all bring your guitars to school? We can stash them in my office before assembly in the morning, then at lunch time you can get them out and play.” So my dad was very instrumental for all three of us. We’d play Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran, whatever was American.

Was there any hint of Bowie’s theatrical side back then?

I remember my dad coming home from school one day – this was before I met Dave – and saying to my mum: “You know, Peggy, there’s something very strange about that Jones boy.” And I’m all ears. “Because on Friday, I’d swear he had eyebrows” [laughs]. So I think David was already being different.

What was the first ever record you bought?

The Everly Brothers’ single (’Til) I Kissed You. My dad didn’t like it, so I had to smuggle it into the house and only play it when he wasn’t there. Then he heard it one day, and came into my room with his arms folded, frowning [laughs]. Years later, when I moved to Nashville, I got to meet Chet Atkins, who played guitar on and produced that record. I was a fan of all guitar players – Hank Marvin, Duane Eddy, Kenny Burrell.

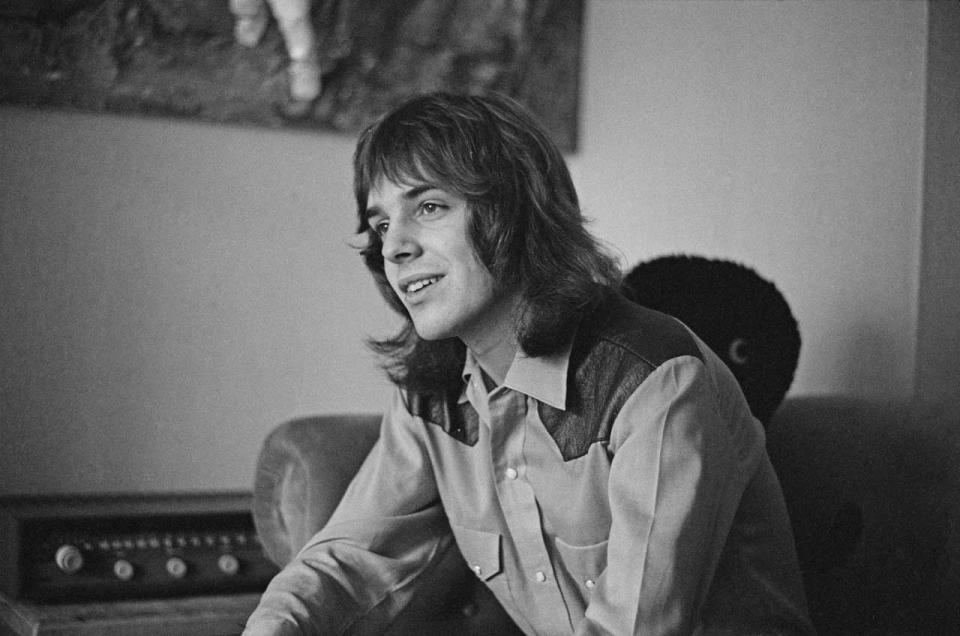

When you were sixteen you joined The Herd and had your first brush with pop stardom, but more as a vocalist than as a guitarist.

I had been in the band not even a year when we started doing the residency at the Marquee club on Saturday nights in the summer. It was the place to be seen. Everybody hung out there – The Who, The Faces. That’s where we got our record deal. I was asked to join as the guitar player. I did some ‘ooh’s and ‘ahh’s in the background, and I sang a Ray Charles number called Hide Nor Hair. I thought, I’ve got an okay voice, nothing to write home about. It’s my guitar playing where I manage to translate my emotions into music.

So you were a reluctant frontman?

It was out of my control. Our managers Howard and Blaikley had seen me sing the Ray Charles song, and the way I looked was perfect for the cover of Rave! and all these teenybopper magazines. We went round to their apartment in Swiss Cottage and they played us this song, I Can Fly. Honestly, it didn’t sound very good. But they said: “And Peter’s going to sing it.”

And it was one of those cartoon double-take moments [makes silly noise and laughs]. We were all in shock. Somehow, the band agreed to it and I went along. It wasn’t a big hit, butit got us noticed. Then they wrote From The Underworld, which I sang, and we’re on Top Of The Pops, meeting Cliff Richard and the Bee Gees. That’s when all ‘The Face’ stuff started; they didn’t put The Herd on the covers of the magazines, they put me on. And instantly it started discontent in the band. I felt terrible. The die was cast.

How quickly did you tire of being ‘The Face’?

Being chased and having your clothes ripped off by girls was all very exciting, but it got old very quickly. And I could see what that was doing to the band. And as I was to experience later in life, a teenybopper in the band can rid you of your credibility. My guitar was now slung behind my back most of the time. And being screamed at by girls during a show also got old really quickly. You realise that they weren’t listening. Not that I’d ever compare myself with The Beatles, but they said it best: [adopts Liverpool accent] “Why would we want to play if they can’t hear us?”

“What Humble Pie enabled us to do most of all was start over, on a musical level rather than on an image level,” Frampton says of his next band experience. Right from the first time he saw vocalist/guitarist Steve Marriott playing with the Small Faces on TV pop show Ready Steady Go!, Peter knew that he wanted to make music with him. And after the pair met in late 1968 they wasted no time in starting a group.

The first version of Humble Pie – guitarists/ vocalists Frampton and Marriott, drummer Jerry Shirley and bassist Greg Ridley – lasted only two and a half years, but they made an indelible mark with four studio albums, plus one of the all-time great live records, Performance: Rockin’ At The Fillmore. “We made great records,” says Frampton. “But we were something else live.”

Steve Marriott had also had the ‘cute’ problem in the Small Faces. Was that part of the motivation for both you two to form a proper rock band?

Definitely. The first thing was, we decided that we wouldn’t shave or bathe! We all grew beards and didn’t wear groovy clothes. We wanted to be accepted for our musicality. We released our first single, Natural Born Bugie, and guess what? We’re back on Top Of The Pops again and we’re being screamed at.

After that we did release another single, Big Black Dog. But Steve was rude to Tony Blackburn, the DJ on Top Of The Pops. He kept calling him by the wrong name and would answer his questions with: “Dunno. Ask our manager, mate.” The result of which was we were never allowed back on the show. I guess we just hated that we were in the same predicament as the two bands we’d been in before. So at our next band meeting we said: “We need to get out of here. Let’s go to America.” They didn’t know us there. That’s when we met Dee Anthony. He started managing us and things really started happening.

In your book, Do You Feel Like IDo?: A Memoir, you say Marriott was the best teacher you ever had for how to deal with an audience. What specific things did you learn from him?

He used humour with the audience. He was a very funny guy. And he wasn’t afraid to speak out when he felt it wasn’t safe out there in the crowd; he had stopped fights by stopping the band and addressing the people. Also, how to deal with people heckling and all that. Again, with humour. Make fun of them if they’re making fun of you, and the audience loves that. Self-deprecation is something else. That’s very much me, and it was very much Steve.

I guess we all get big-headed if we’re entertainers, at some point or other. But I think it was more the insecurity at the root of it. Steve was very insecure. Obviously, one would say: “What the hell for?” He’s got this incredible voice and incredible guitar playing. I’m insecure too. Most artists are. Because, basically, you’re putting your art out there for the local art reviewer to come and pull to pieces.

In live videos of Humble Pie, Marriott seems to be almost possessed by the spirit of an old blues singer. Was that also your sense of him when he was on stage?

If there was ever someone who was born with an overabundance of soul, it was Steve. Where it came from I have no idea. But he threw himself into it a hundred per cent. It all came out of this tiny frame – Steve was five-foot-nothing. As I say, he was very insecure, but when he opened his mouth and sang and played he was something spectacular. I’ve no idea how he accessed that. He gave his all every night.

It was phenomenal to watch, and it made you, as a player, go to the ends of the earth too. Because if he’s giving his all, I have to match that. He affected us all greatly. That’s why we were such a fiery band on stage.

With the music he listened to, was he obsessive about blues artists like Muddy Waters and Lightning Hopkins?

Definitely. Especially Muddy Waters. But the Staples Singers were his absolute favourite. In fact when I listen to Mavis Staples’s version of Oh La De Da, I realised that’s where Steve got a lot of his vocal stuff from. He sings like Mavis. Steve listened to everything. He was a big country fan. All kinds of music, though not so much with the jazz [laughs].

When he didn’t like something, you knew it, he didn’t hold back. But he loved the more rootsy stuff. When we got first got together and he wrote Natural Born Bugie, he said: “I’ve got a suggestion for the guitar solo on this,” and he played me the Bill Black Combo. Steve was very much into Bill Black. I eventually lifted some licks from one of Bill Black’s records and put them into Natural Born Bugie.

With Humble Pie live, even when you’re off in your own worlds on stage, there was an almost telepathic connection between you, Jerry, Steve and Greg.

We were great listeners to each other. Yes, we were there to play our part, but our part was part of the band. Therefore I’m listening intently to the other three, and without thinking about it my brain is working out: “What do I need to do here? Do I need to do more or less at this particular moment?” Then sometimes Steve would conduct us, quieten us down – “Hold it, boys.” And we’d all come down, then he’d do one of his wails and you got chills. I am so lucky to have been part of that band, I can’t tell you. It did more for my musicality, my playing, my writing, my sense of how a band should be. Humble Pie just brought it all together for me.

How did the Pie song I Don’t Need No Doctor come about?

We were opening for Grand Funk at Madison Square Garden. It was our first time playing there. We actually got a sound check, which is unusual for an opening band. My rig was the first one to see the red light, so I picked up my guitar as Jerry was just about to sit down at his drums. I turned up and played the loudest E chord I could play, in an empty 22,000-seat Madison Square Garden – the original size. That chord just filled the place.

I went: “Oh, wow!” We’d never been in a room that big. Then I played an E-minor, G and A, and for some reason I went [sings lick to song]. Jerry yelled: “One-two-three-four!” and he was in. Then Greg fell in. Steve was at the mixing console a mile away, and I saw him sprinting full-speed towards the stage. He didn’t even pick up a guitar. He gets to the mic and yells: “Hold it on the E! ‘I don’t need no doctor!’” And that was it. Steve picked up a guitar, then we did it again, we arranged it, rehearsed it, and it became the last number of our set that night. It tore the place apart.

We saw the power of the song, and it became our closer of every show we ever did. That was Humble Pie – all we needed was a riff and we were off. And that was one hell of a riff.

The early seventies was the era of notorious rock managers: Don Arden, Peter Grant, and Dee Anthony who managed Humble Pie and your solo career. Anthony had ties with the Mob. Do you think the upsides of working with him outweighed the downsides?

Boy, that’s a loaded question. Put it this way: we wouldn’t be sitting here talking today if it wasn’t for Dee Anthony. I give him kudos for his clout, his pushiness. I don’t know how involved in my career the Mob were, but I know that he had to pay them. I found that out. The bigger Humble Pie got, or the bigger I got as a solo artist, the more he had to pay them. You don’t ever get out.

Dee had a side of him that was ruthless and greedy. He was… a crook [laughs]. He would rob me to pay Humble Pie, and rob Humble Pie to pay me. All I ever wanted was to be known as a halfway decent guitar player, and now here I am the biggest act in the world for a couple of years. And all the money went through him, while very little filtered on to me, shall we say.

Frampton left Humble Pie in 1971, just as they were reaching a commercial peak with the Fillmore live album. Marriott’s increasing drug use was causing friction between the two friends (“Steve and I were brothers, but he could be very difficult”), but Frampton’s decision to strike out on his own was motivated more by musical differences.

The softer acoustic ballads and more sophisticated, jazzier songs he was writing didn’t fit with the Pie’s whisky blues-rock roar. But before he signed as a solo artist with A&M Records in 1972, he had a fertile period of being a sought-after session musician, and played with George Harrison, John Entwistle, Donovan, Jerry Lee Lewis, Jobriath and Harry Nilsson, among others.

In 1970 you became a friend and musical cohort of George Harrison. How did that come about?

Terry Doran, who is the ‘man in the motor trade’ in [The Beatles’ song] She’s Leaving Home, was John Lennon’s personal assistant, then he became George’s. Terry was a known figure in town in the clubs. I didn’t know quite what he did. We’d meet up in this pub called The Ship, just up the road from the Marquee. One time, I’m there, and he said: “Do you want to come and meet Geoffrey?” I said: “Geoffrey who?” “You know, George.” That was his code name. All the Beatles, like the presidents, had code names [laughs].

So we went to Trident Studios, just down the block. I was very nervous. It was my first Beatle meeting ever. We walk in, and there’s George behind the console. He says: [pitch-perfect George] “Hullo, Pete.” I thought: “Did Pete Townshend walk in behind me?” I had no idea that a Beatle would know who I was.

And you were immediately pressed into playing guitar.

Yes! It was: “Nice to meet you, man… Do you want to play?” I said: “You mean now?” They’d just finished writing this song for Doris Troy, called Ain’t That Cute?. So he gave me ‘Lucy,’ that red Les Paul that he used on a lot of later records, and the one Eric [Clapton] played on While My Guitar Gently Weeps. I plugged in, and I can’t take my eyes off George, because I want to get this right. Then I glanced to my right and there’s Stephen Stills sitting there. What?!

George showed me the chords, and I’m playing very quiet rhythm. He stops the tape and says: “No, I want you to play lead.” Then I started to sweat a little [laughs]. But I ended up playing the lead fills and intro on this song that was a single.

That led to you playing on George’s album All Things Must Pass.

George called a few weeks later and said: “Pete, I’m doing my own album with Phil Spector. Would you come and play some acoustic? Phil wants, like, nineteen of everything.” I was there for a week. We did If Not For You, Behind The Locked Door, My Sweet Lord and a few others. Two weeks later, George calls me and says: “Phil wants more acoustics.”

So that time, it was just me and George sitting on two stools in front of the glass at Abbey Road, and there’s Phil Spector. It was very surreal. It’s one of those moments that I will never, ever forget. Phil loved the way it sounded, so we started adding it to a bunch of tracks. In the end I don’t know how many songs I played on in total. But if you hear an acoustic guitar I’m probably on it.

For all of his eccentricities, do you think Spector really had something special in the studio?

Yes. Firstly, you have to remember that Phil is not used to the artist coming into the control room. Fuck that. You’re going to tell George Harrison, Ringo, Gary Wright and Billy Preston they can’t come in to listen? No, that’s not the way we work over here. So Phil looked petrified when we’d all come in the control room [laughs]. He was complaining about his stomach ulcers all the time.

But say there are five acoustics and seven other players. In the headphones it just sounded like what it was. But when we walked into the control room to hear the playback, it was like there were twenty thousand people on the track! It was instant, a phenomenal turnaround.

Every tape machine was rolling, every echo chamber was turned on. It was the [Spector’s legendary] Wall Of Sound. And I have to say, I love the new mixes they did on All Things Must Pass last year. There’s more vocal. But there’s something about Phil’s original mixes that was magical.

Another successful album you played on was Harry Nilson’s Nilsson Schmilsson. What was your take on him?

He was another one of these phenomenal artists who kind of took me under his wing. George said to Harry: “You should use Peter on your album.” So I get a call from Harry. He had a heart of gold. He was petrified of performing, but loved the studio. He had a lot of insecurities too, and of course that led to his later period where he was self-destructive. But everyone loved Harry. He was funny, very bright, and quick to say how much he liked something. It was a pleasure to work with people who appreciated what you did.

And in 1973 you played on Jerry Lee Lewis’s album The Session. Given his reputation, was that intimidating?

Not for the reason you’d think. There was Albert Lee, Rory Gallagher and me. It was produced by Steve Rowland, who produced The Herd. That’s why I got the call. So we’re all sitting outside in the anteroom, and you’d hear: “Okay, guitarist number three, come in!” Each one of us did a track with him, then all three of us played together on a track. Basically, it was Albert’s band Head, Hands & Feet as the backing band. Jerry Lee was very cordial, very appreciative of us being there.

It was nerve-racking for me in a different way, because I remember watching Albert Lee at a club from the front row and thinking: “Oh my god, I’ll never be that good.” I felt the same about Rory. It was very intimidating to be with those two, but I held my own. I think I enjoyed it more afterwards [laughs].

The same year, you also played on Jobriath’s self-titled album, the fabled glam-rock disaster. What are your memories of being in the studio with him?

It was around the time I was doing Frampton’s Camel at Electric Lady with Eddie Kramer. Eddie was the producer on the Jobriath album. I just remember Jobriath being really nice, with these odd, slightly complex songs. I was enjoying being a session guy, where people were throwing stuff at me that I had to really think about, bringing my style to whatever was in front of me.

That was the thing. I was the kind of session guy that you didn’t hire to say: “Okay, I want you to play like Eric Clapton.” The engineers and producers who hired me knew that I would bring Peter Frampton’s style to the record. That’s what they wanted. I’m not very good at mimicking other people. Except for The Shadows. I can still play all of those songs note for note.

Frampton’s Camel was one of four solo albums you released in rapid succession in the early seventies, leading up to Frampton Comes Alive!. It seems like your label, A&M, really gave you room to grow and develop your sound.

It was my discovery period. I was learning how to sing properly. I was becoming more relaxed and creative, getting better as a songwriter. When Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss started A&M, they said: “If we’re going to form a label, let’s make it like United Artists.” The reason that all the actors formed United Artists was to get away from all the bullshit of other people’s egos.

Herb said: “Let’s sign artists that we like, and let them do their thing.” That was their criteria. Simple as that. It was the fifth album for me that finally clicked. Frampton [his fourth solo record, in ’75] sold pretty well, but it wasn’t until Comes Alive! that things broke open.

That’s an understatement. For about eighteen months, beginning in early 1976, Peter Frampton was the biggest rock star on the planet. How did it happen? First, through years of non-stop touring, opening shows for everyone from Black Sabbath to The Kinks to ZZ Top, he had built a loyal following.

Second, the set list-of romantic hits such as Show Me The Way and Baby, I Love Your Way and guitar-shredding jams like I Wanna Go To The Sun and Do You Feel Like We Do? that made up Frampton Comes Alive! perfectly framed his strengths: the controlled fire of his lead playing, his unpretentious, soulful voice, his accessible songwriting, the talk-box. It was all there in one appealing package.

And then there was his band – keyboard player Bob Mayo, drummer John Siomos, bassist Stanley Sheldon – who were one of the tightest, most versatile of the era. Frampton is quick to point out that his breakthrough wouldn’t have happened without the emotional chemistry he had with them. “It was the best band I’d ever had. That lineup came together in 1975, so it was a new band, but it gelled so quickly that it took us to a WNL – whole ’nother level,” he says with a smile.

When did you realise that Frampton Comes Alive! was going to change your life?

1976 was going to be the first headline tour for me. I’d been in the middle position for years, being a great support act. I sold tickets, but I was still playing with other bands. As the album was coming out, I went away to the Bahamas for ten days. Before I left, my agent Frank Barsalona said: “Guess what? You’ve sold out a show at Cobo Arena in Detroit.” I couldn’t believe it.

Ten days later we’ve sold out three nights at Cobo. That’s when I thought: “Wow, what’s going on here?” Comes Alive! was just starting to get played at radio at that point, and it just kind of took off immediately. As for why it turned into what it did, I still don’t know.

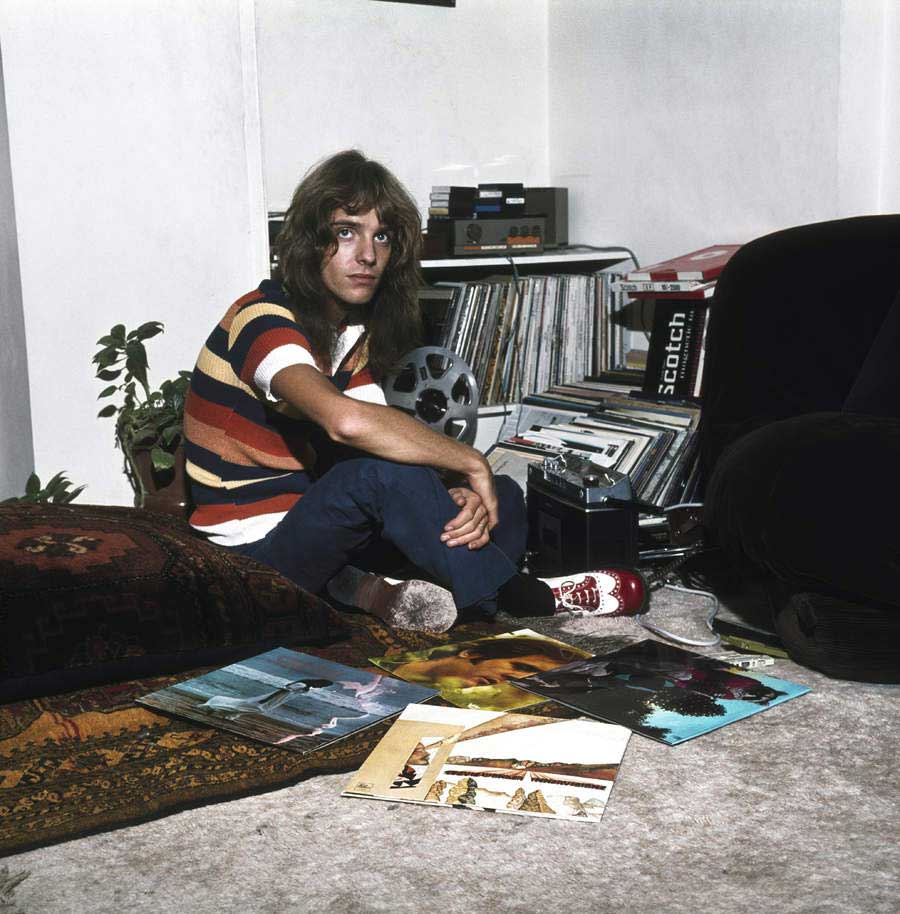

What did you do with your first million-dollar royalty cheque?

Ever since I was twelve I’ve been a gadget freak, an audio freak. Across the street from A&M in LA there was a studio supply place, and the bank was next door to A&M. So I deposited the cheque, then walked across the street and for the very first time in my life I was able to say: “I’ll have four of those, please, I’ll have two of those…” I bought all these mics and outboard gear and a multi-track tape player – the innards of my very first studio. It probably wasn’t fifty thousand dollars in total. But that was the first thing I did with the money.

It’s interesting in your memoir, at the moment Comes Alive! hits Number One on every chart, your reaction is a mix of shock, excitement and worry. You mention the little guy on your shoulder saying, “How are you going to follow this?”

I’ve used the word ‘surreal’ before, but that level of success took some getting used to. There was one week where we sold a million copies. The little guy on my shoulder appeared when I got the call that we were Number One. I was really excited at first, but the album stayed there for so long that I got the second call from Dee Anthony and he said: “Are you sitting down? You’ve just broken Carole King’s Tapestry record – you’re now the biggest-selling album of all time.”

That’s when I got scared. Because I now realise I have to follow up a live record that is not just a hit, but the biggest record of all time. I had help in the substance abuse area around that time, because everyone was abusing themselves then. I didn’t have to, but I did, and that was partly the reason – because I was scared stiff.

And the follow-up, I’m In You, happened too fast.

I absolutely did not want to record I’m In You. I knew that you’re only as good as your last record. I wish I had taken my time. But I had to sift through everyone’s agenda. I’m twenty-six years old. My brain hasn’t finished growing yet. And I started making bad decisions, by going along with what everybody thought. “You’ve got the biggest album ever, so you want to follow this up as quickly as you can because otherwise people will forget you!” “People aren’t going to forget me…” “You don’t know that.”

I always quote the Eagles story here. You’d think with their long career they’d have twenty-seven studio records and four live albums and several ‘greatest hits’. They’ve only had eight albums. They don’t go near the studio until they’ve got incredible songs. I could’ve waited three or four years. Other artists have. But the other side of the coin was Jerry Moss saying: “The longer you wait, the harder it’s going to be.” That’s true too. But it wasn’t to be.

At the same time, there was the infamous photo of you shirtless by Francesco Scavullo that appeared on the cover of Rolling Stone. It was really damaging, wasn’t it?

Yes it was. I had a fifty-fifty male/female audience up until I’m In You was released. Throughout the year, as Rolling Stone, then more magazines, came out with me on the cover with my shirt off [grimaces], at my shows the guys went to the back of the hall and the girlfriends came to the front.

So now I’m hated by the guys and loved by the women. I’m back in the same position I was in The Herd. And it was so frustrating, because I couldn’t control the way I looked. There’s an assumption: “Oh, you got there because of your looks.” And I’m thinking: “Hold on, I really didn’t. I fought my way up as a guitar player.”

Bill Wyman was my first believer and discovered me when I was fourteen, as a guitar player. George Harrison appreciated me as a guitar player. David Bowie appreciated me as a guitar player. They all knew; people in the business knew. But everyone’s looking at these magazine covers and thinking: “Poor Pete.” It’s not what I wanted at all.

Speaking of Bill Wyman, you were in the running to become a Rolling Stone after Mick Taylor left. Do you ever fantasise about how that would have played out?

Every day [laughs]. No, not really. It was Charlie [Watts] and Bill who put my name forward, because I was closer to them than to the others. But then when we were doing I’m In You, Mick Jagger was in Studio A at Electric Lady and I was in Studio B. I think he was mixing a Stones live album.

One day, I bump into him and say: “Okay, I’ve got to ask. I heard it on the radio, and Bill said that he submitted my name. Was I one of the top five people in the running?” And Mick said: “Yes, you were.” I said: “So what happened?” And he said: “Well look where you are now. We knew you were just about to break.” That was a great excuse.

The talk-box is such a big part of your signature sound. Why did it appeal to you?

Let me give you the background first. When I was a kid, we had a station called Radio Luxembourg, and there was a DJ called Kid Jensen, who went from seven to midnight. So when I’d go to bed, I’d take my little transistor radio and tune in. Their call numbers were 208, and the station ID would go: [sings in robot voice] “Fabulous two-oh-eight.” It was this cool, ‘computerised’ sound. And I’d think: “How do they do that?”

Many years go by. I’m with George Harrison in Abbey Road, and I meet Pete Drake, this fabulous steel guitar player from Nashville. He’s played with Dylan on Nashville Skyline, and George has brought him over. And Pete showed me this talk-box. When the pedal steel started singing to me, I thought: “Eureka! Fabulous two-oh-eight.” There it is. A completed circle.

I said: “Where do I get one?” Pete said: “Well I made this one myself.” After that, Pete lent his talk-box to Joe Walsh, who used it on Rocky Mountain Way. Then Joe asked his audio engineer Bob Heil: “Hey Bob, I’ve got this talk-box from Pete Drake but it’s not loud enough. Can you make me one that’s louder?”

I knew Bob, and he gave one to my girlfriend to give me for Christmas. I locked myself away for a couple of weeks and learned how to talk with it. I thought: “Wouldn’t it be great if I could say hello to the audience through this talk-box?”

How was it the first time you used it on stage?

I probably did it first in 1974 on that tour, on Do You Feel. It was insane. It felt like the whole audience moved a foot forward towards the stage. It was a jolt, where you felt them saying: “What is that sound?!” The more I would talk, and ask them questions, it just kept getting crazier. The ultimate moment was me just saying: “Do you feel?” “Oh my god, yes, yes, waaaaaaahh, we do!”

It exceeded my wildest dreams. Then we introduced it into Show Me The Way, and the rest, as they say, is history. This moment coincides pop-culture wise with Star Wars, and our fascination with cyborgs and robots. Maybe it was as simple as people thinking: “It’s Peter Frampton as a robot.”

We had this guy who built this replica of R2-D2. For our encore, this life-sized robot with my guitar lung over its shoulder would come out and give me the guitar. The audience went nuts. Then we got a cease-and-desist letter from [Star Wars creator] George Lucas [laughs].

Something in your book that made me chuckle was your confession that ironing clothes was part of your pre-show ritual.

Yes. I think it was that Zen thing of a repetitive activity relaxing your mind. Also, I had read that Eric Clapton would iron before a show, so Ithought I’d try it. I’m fairly fastidious about having no wrinkles in shirts, so it would always be the shirt I was ironing. I guess you couldn’t touch an iron to satin pants… [Laughs] Now, now, now, that was a long time ago, we shan’t talk of satin pants.

The Sgt. Pepper movie, in 1978, was an infamous disaster. What do you recall most about it?

On my first day on set, I remember feeling: “I’m making the biggest mistake of my life doing this.” I’d said yes against my better judgement. But George Martin was producing the music, and Robert Stigwood, who put the movie together, was on a winning streak with Grease and Saturday Night Fever. Also, he promised me that Paul McCartney was going to be in it. I thought: “If a Beatle’s doing it, then I will too.”

Then I saw Wings play at Wembley, and I remember Linda said: “Paul, Peter’s going to be in that movie.” And I said: “You are too, right?” “No, no, I’m not in it.” And I thought: “Uhoh.”

Three or four months in to the shoot, I think all of us were thinking individually that this thing is a disaster. But no one spoke up. At the start, no one thought we could lose. We’ve got the Bee Gees, Peter Frampton and Alice Cooper. How can it fail? Well, it would be good if there was a script. It was such a stupid storyline. If we were making a movie for five-to-seven-year-olds, we made it.

There’s a clip on YouTube from around the same time of you acting on the show Black Sheep Squadron with Robert Conrad.

Did you have aspirations to continue acting? Yes and no. My daughter still wants me to be on an episode of Law & Order SVU. I could play the old guy on the street with the cup, saying: “Just put the money in here,” while dribbling, but who, it turns out, is the witness they really need [laughs].

In 1978 I got a three-picture deal with Orion. I remember sitting around the conference table with all the execs, and they were saying: “We have some ideas of what we’d like you to do…” This was before Sgt. Pepper came out. When it came out, I said to Dee, my manager: “When do we get our first script from Orion?” “Um, I’ve got some bad news. We don’t have a deal any more.”

Anyway, around that time, I saw Robert Conrad at a famous restaurant in LA. I’m a huge fan, and Isaid: “If you ever need a walk-on on one of your shows…” Ten days later I get the script. A Little Piece Of England, it was called. And my character was on every page. I was like the guest star. I wasn’t very good on the first day of shooting, because I was nervous. But I improved. I learned my lines and everybody’s lines. I wanted to be on it. Barry Gibb asked me why I did the show, and I said: “Because we just spent six months making this shitty movie [Sgt. Pepper], and I haven’t said a damned word.”

My only line in Sgt. Pepper was reading a telegram – and they put George Burns’s voice in my mouth. I wanted to find out what it was like acting. I was going to have fun and be on a programme with my favourite actor. I had more fun in that week than I did in six months on Sgt. Pepper.

To add injury to insult, the weekend that Sgt. Pepper opened, Frampton was in a bad car accident while on holiday in the Bahamas. During the month he spent recovering in hospital, he took stock of his career. In his memoir he says: “I had time to examine my relationship with Dee Anthony, and start asking: “Where are my publishing royalties? Where are my record royalties?’” He hired a lawyer and started extracting himself from his contracts.

Like a lot of 70s rockers, Frampton soon found himself adrift in the 80s glossy landscape of synthpop, drum machines and slo-mo MTV videos. “It was my lowest period,” he says. And then after his Premonition album in 1986 he received a life-saving call from an old friend.

After struggling to recapture your groove in the eighties, your old schoolmate David Bowie called you out of the blue. What did that mean to you and your career?

It meant everything to me. David was a man who reinvented himself every five seconds. And rightly so. He had an incredible sense of self and of public and of image. He was the whole ball of wax. And we had history – from playing guitars together on the art block stairs at Bromley Tech, to Humble Pie having David as our special guest on the 1969 tour of England. His Space Oddity was number one, and we were number four with Natural Born Bugie. So it was a pretty good tour.

We’re still buddies throughout all this, and of course David was very close with my parents. He invited all of us to see him in The Elephant Man on Broadway. So I get a call in 1986. I’d just got off tour with Stevie Nicks. David said: “Look, I’ve just heard your last record, Premonition, and I love your playing on it. Could you come and do some of that for me?” And I said: “Um, okay.”

So I went to Switzerland and played on Never Let Me Down. While I’m there, he asks: “Would you ever think about going on tour with me?” It was like a sigh of relief. I’m going to play with David finally after all these years. I was so excited, not really realising what it would do for my lack of credibility. My credibility was in the toilet in the eighties. As we would play shows, people were remarking on how great it was that all of a sudden I’m a guitar player again. There was this solo spot at the end of Loving The Alien where I could go off and solo for four minutes.

The gift that David gave me was just wonderful. He knew what I was going through and that I’d lost my cred. He singlehandedly gave it back to me. And I could never thank him enough. He could’ve had any guitarist, but he chose me.

Did he have any pre-show rituals?

Dave would have a hairdresser and make-up person, because that’s what he did. He wanted to look a certain way. I think those moments were his time for preparing for the show. Sitting in that chair, while people are doing things to him, he’s all tunnel-vision, just inside himself, concentrating on everything he needs to do in the set. Meanwhile, I would be limbering up on guitar, and he’d shout across the room: “Oh, that sounds good, Pete!”

Playing live with him you were basically covering several iconic guitarists: Mick Ronson, Robert Fripp, Stevie Ray Vaughan… Was that daunting?

I knew most of Dave’s songs, of course. Everyone does. Basically, I would go back and listen to what those guitarists did on the records, then I would hint at it so that it wasn’t too different. Signal what people remember, then go off into my own area, as if I had played on the original track, whether it was “Heroes” or Scary Monsters. Like I said when we were talking about session work, it’s my style that comes through. I’m not a guy who can say: “Now I’m going to be Adrian Belew”, “Now I’m going to be Robert Fripp.”

There’s a video on YouTube of you and Bowie walking around Madrid looking for somewhere to get a beer. The camaraderie is obvious. Did you flash back to school days and have certain favourite inside jokes?

Hmm, inside jokes, probably, but I can’t remember exactly. But I can tell you that David would always quote my dad. Because my father Owen was a bit like a surrogate father to him. David was a great mimic and a great actor, so he liked to speak in these different voices. We both had the same sense of humour too, because we grew up on The Goons first and then Monty Python. And we also both liked a drink at that point, so we could be quite dangerous together [laughs].

I love the song The Bigger They Come that you wrote with Steve Marriott in 1990 for the proposed Humble Pie reunion album. What happened with that project?

When we got back together in England, we wrote a song the first day. I said: “Do you want to take this further?” He said: “All right, mate.” So I invited him to LA, where I was living at the time. So he came and got a place in Santa Monica. I had a makeshift studio in North Hollywood, and we would be there every day. I said: “There’s only one way I can do this, Steve. We have to work sober.” I wasn’t drinking much at all by that point. He said: “All right, mate.”

We worked for about two weeks. We had a bass player and a drummer and we were jamming. It was going great. We wrote I Won’t Let You Down, The Bigger They Come, Scratch My Back… Then I noticed he was starting to slur a little. He had a Perrier bottle, and I realised it was white wine in it. I just said: “I can’t do that, Steve. It’s not good for me, and it’s not good for our relationship.”

We had a business meeting set up to talk about a record deal, but Steve never made it to the meeting, saying he got lost driving in from Santa Monica. I think he was always scared of big success, always scared to be pushed out there. If we’d made the record, we didn’t plan to call it Humble Pie, we wanted to call it Marriott-Frampton. But the label people all wanted it to be called Humble Pie. The name recognition thing. But we said no, that was in the past. But with the drinking, finally I just said: “Steve, I’m sorry, this is not going to work for me.” And that was it, really. He said: “All right, mate, I understand.”

He did call me one more time before he went home to England, but he was incoherent. That just made it worse for me. It was very sad. I thought that he would go home and he’d think about it, then call me to say: “Let’s give it another chance.” And I believe he would have. But of course the day he got home, he fell asleep with a cigarette in his hand. And the rest is history, unfortunately.

In the mid-90s, Frampton joined Ringo’s All-Starr Band, touring alongside friends including Jack Bruce and Joe Walsh. In 1998 he released Frampton Comes Alive II. Lightning didn’t strike twice, but his humble aim was to keep reminding listeners what he did best. “I’m a live performer,” he says.

The new century started with Frampton acting as a musical consultant, player and songwriter on Almost Famous, the blockbuster film written and directed by his longtime friend, former Rolling Stone writer Cameron Crowe.

You were an important part of Almost Famous. As well as writing songs and playing on the soundtrack, your job was making sure the band, Stillwater, looked authentic. You also had to teach guitar to actor Billy Crudup.

I felt like I had so much information to bring to the movie, because I’d been through it all. I opened for Black Sabbath, just like Stillwater. Rock movies hardly ever look right, you know? So I think Cameron wanted to make sure every detail was there, right down to what mics were right for the period.

I enjoyed all the gadget part of it, but my main job was to make Billy Crudup look realistic. He had to be a mix of Jimmy Page and Paul Kossoff; they would watch movies of Led Zeppelin and Free. That’s what it was based on. It’s me and Mike McCready from Pearl Jam playing on the tracks. So I would learn the parts and show Billy what to do.

He was like a sponge. Whatever information you gave him, he remembered. All the actors were like that. Cam asked me: “How will we know when Billy has it perfect?” And I said: “He’ll have his fingers in the right place at the right time and he’ll put his head back and he’ll close his eyes.” That’s the moment we waited for.

And you got to direct a scene.

John Toll, the Academy Award-winning cinematographer, comes up behind me and puts this huge pair of headphones with the microphone on it on my head and says: “You know the music better than I do. You’re going to be calling the cameras.” I said: “What?!” So I actually got to control four big Panavision cameras while we were shooting the concert scene. There I was going: “Okay, drum fill in three-two-one, go!”

I enjoyed it so much. And then Billy was doing his guitar solo, and he got everything right: fingers on the neck, head thrown back, eyes closed. “Oh my god, we got it!” Cam and I were high-fiving.

Have you been approached about doing a film about your life?

We are in the process of making a documentary. Covid messed with us, obviously. We stopped, and now we’re waiting for the final funding to be able to continue. There was a rush on music documentaries and it kind of slowed down. I haven’t been approached to do a biopic. I think it’s a story that’s been told before. But I might be wrong. If they ever do, I hope that Cameron would direct it. He knows me so well.

Do you have any favourite ways that you’ve been portrayed in pop culture?

I think my appearance on the TV show Madam Secretary was such a nice thing. It all started because Téa Leoni’s character was wearing a Frampton T-shirt on the show. I got a written slap from Tim Daly, her husband on the show and in real life, because I said jokingly to Téa: “Thanks for wearing me to bed” [laughs]. But we’re all dear friends.

Then there was The Simpsons. The casting director called and said: “Would you like to be in an episode of The Simpsons?” I said: “Have you got the right number?” Because my career was nowhere at that point. She said: “We’ve got Smashing Pumpkins, Sonic Youth, and you’re headlining a Lollapalooza concert.” I said: “But I wouldn’t be headlining a Lollapalooza concert.” And there was silence.

Then I said: “Oh, I get it. You want me to be the old, crusty rock’n’roller who’s been there, done that, hates everybody?” She said: “You’ve got it.” It was so fun. They let me ad-lib, and what a treat to have them animate me.

In 2007, Frampton’s rock guitar rave-up record Fingerprints won him his first-ever Grammy Award, for Best Pop Instrumental Album. “It was so great to be recognised for something that had no connection to Frampton Comes Alive!,” he says. “It changed people’s perception of me back to how it was in Humble Pie and my early solo days.”

Along with that came a cosmic boomerang moment: the return of Frampton’s iconic guitar, a 1954 Gibson Les Paul ‘Black Beauty’ that was thought to be destroyed. Back in 1980, when Frampton was touring South America, a cargo plane carrying his band’s gear from Venezuela to Panama exploded on the runway. All of the instruments, including Frampton’s prize Les Paul, were lost. Or so he believed. He’s now nicknamed the guitar The Phoenix.

Tell us about the 1954 Les Paul, and how you were reunited with it thirty years after that horrible accident.

The guy that was guarding the remains of the plane that burned up on the runway in 1980 forgot to tell my road manager that he’d already taken the guitars off and sold three or four of them. So my guitars were floating around Caracas, in various different musicians’ hands. For fifteen years the guy who ended up with the Black Beauty was playing it in clubs. Then it got a little hot. People started saying: “Hey, that guitar looks an awful lot like Peter Frampton’s.” So this guy stuck it in the closet and forgot about it.

New generation comes along, and his teenage son says: “Dad, that guitar in the closet doesn’t play well. Can I take it somewhere to get it fixed so I can play it?” “Okay.” Not realising what he was doing, the kid took it to this luthier. He opened the case and the luthier’s eyes almost popped out of his head. He knew exactly what it was. He said to the kid: “Yeah, leave it with me overnight and I’ll fix it up.”

Meanwhile, he called a luthier friend in Holland, sent pictures, and they quickly verified that it was my guitar. I got an email and there were the photos. That was 2010. Thirty years after it had been thought lost. Meanwhile, the kid comes back in the following day, and the luthier says: “You know what this guitar is, don’t you?” The kid shoved it back in the case and ran off.

Two years went by. Then the kid finally comes back and says: “I want five thousand dollars and a new Gibson, then you can give this back to Frampton.” They tell me, but no one wants to bring it to me, because they think I’m going to have them arrested in Miami for stolen merchandise. I said: “No, no, no.”

Finally, the luthier has a friend who’s the minister of tourism for Curacao. So Curacao buy the guitar for five grand, which I paid back. They brought it to Nashville and presented it to me in a little formal ceremony. Like a cultural exchange. There’s a mini-documentary about it all on YouTube.

In 2017, after falling twice on stage, Frampton was diagnosed with inclusion body myositis (IBM), a painless but progressive degenerative disorder that weakens the legs, arms, wrists and fingers. He announced his condition before embarking on a farewell tour in 2019, which the pandemic then interrupted halfway through and the rest of the shows were postponed.

So three years and further postponements later, Frampton is playing what will be his final live shows. For all the anxiety he admits to having about it, he still comes across very upbeat. “I think of my parents,” he says. “During the Second World War my mum went through the Blitz, my dad went through every major battle in Europe and Africa, and they survived. That’s why I’m able to pick myself up.

You’ve already completed more than half of your farewell tour, with the final dates coming this autumn in the UK and Europe. How has it been so far?

The American-Canadian portion was the most moving tour I’ve ever done. It’s very emotional for me saying goodbye to anybody, let alone ten thousand people a night. They wouldn’t let me leave the stage. In the end I had to say I’m not going to say goodbye, and I just waved. As I turned my back every night I’d well up. All of a sudden, in every city we played, every fan that ever was there in the seventies was back again.

It was like the old days. Everything had come back around again. The crowds were unbelievably appreciative and warm. Different audience every night, but same emotion. I can’t thank people enough for what they’ve given me. I’m a live performer above all, so that’s the most moving thing for me. I don’t know what to expect in the UK and the EU, but I’m hoping it’s going to be along the same lines, because we had a blast.

How are you managing with your IBM?

Well… my legs are not good, and I’ve decided I am going to sit down on these upcoming tour dates in Europe. I can’t stand. That would be dangerous for me now, because I get so carried away when I’m playing that I’m liable to fall over [laughs]. It’s starting to affect my hands, but not enough yet, so I can still play a good lick. But I’ll be honest, I’m anxious about it. I haven’t played over there in so long, and I have progressed in my disease.

You played your first gig in more than a year, at Buddy Holly’s 85th Birthday Celebration. How did it go?

Well, I sat down for the first time ever on stage. And… it felt very comfortable [laughs]. Better than leaning on a piano. It was me, Steve Cropper, Albert Lee, Duane Eddy, a few others. We each did one Buddy song. The reason it meant so much to me is that the very first song I learned on guitar was Peggy Sue. I was probably nine years old. That would’ve been 1959. Peggy Sue came out in 1957. So it took England by storm. Buddy Holly was as big, if not bigger, in England than he was in America.

So we did Peggy Sue, then we did Lines On My Face and Do You Feel. I told some stories and cracked a couple of jokes. It was fantastic. The warmth from the audience was just like the final tour. In your memoir, you say of your career: “There’s never been a master plan.”

If you could go back, would you change anything?

Only two things: I would’ve waited to make an album after Comes Alive!, and never put out I’m In You. Breakin’ All The Rules would’ve been a much better follow-up record. And I wouldn’t have done the Sgt. Pepper movie.

Any final words?

What did my mum used to say? “What is to be, will be sure to come true.” I don’t know what it means, but I’ve always lived by that [laughs].

This interview originally appeared in Classic Rock 306, published in September 2022.