“You pick five interesting guys, lock them in a room together… and if they make an album without actually killing each other first, it will at least be an interesting album”: How King Crimson made Larks’ Tongues in Aspic

In 1973, King Crimson released their fifth album, Larks’ Tongues In Aspic. It marked the beginning of a new era for the band, with a revised line-up but and a more dynamic sound. In 2023 Prog looked back on the making of a record that remains unique.

By April 1972 King Crimson were in serious disarray. The group who had caused such a stir in 1969 with their live shows and their debut album – the epochal progressive rock statement In The Court Of The Crimson King – had gone through three line-up changes for each of their three subsequent and sporadically brilliant studio albums: In The Wake Of Poseidon, Lizard and Islands. But what had once looked like the most promising band of the early 70s now appeared to be the most unstable. King Crimson had, it seemed, essentially ceased to exist.

Guitarist Robert Fripp’s uneasy artistic relationship with lyricist and co-founder Peter Sinfield had ended. Fripp explained to Richard Williams of Melody Maker that he “didn’t feel that by continuing to work together we could improve on what we had already done.” And the line-up that had recorded Islands and toured the US in 1971 was falling apart. Another US tour had been booked and they flew out in January to fulfil their contractual obligations, but on their return in April the break-up was made official.

No one but the most gifted seer could have predicted then that within a year a new version of the group would release an album, Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, which would not only be the equal of their debut, but one of the most audacious, inventive and imaginative albums in the whole of 70s progressive rock.

Even before the break-up, disgruntled Melody Maker reader Fred Foster had written in to the paper complaining that the most recent line-up “had no more right to the name KC than Emerson, Lake & Palmer and McDonald and Giles.” He added: “To simply give the new group a new name would clear the confusion by showing that Crimson is dead.”

Mr Foster was closer to the truth than he’d realised. Unbeknown to the public, Fripp had started playing in a trio with violinist and keyboardist David Cross, who he’d seen play with Waves – and who had been trying to get a deal with EG, the company that managed Crimson – and percussionist Jamie Muir. Fripp’s initial idea was to record a raga-style improvised album and the trio had played together at Muir’s house in Highbury, London.

“That was all fantastic,” Cross tells Prog, “but I didn’t join a pre-existing band called King Crimson. It never had a name beyond ‘Indian-style improvisation album.’ Robert probably wouldn’t have had the support of his manager if he had done something like that. Then something shifted, whereby he put the two things together.”

The original line-up of King Crimson had split up in December 1969, less than three months after the release of their debut album. In 2012, Fripp told this writer, “It was heart-breaking; but there was still something there to be pursued and I knew that whatever we did in the next two years – this was Peter and myself – would be wrong. But we had to do it to get to the other side.”

The “other side” that Fripp spoke of was the fifth incarnation of King Crimson. It was heralded in July 1972 by the surprise announcement that drummer Bill Bruford had quit Yes to join the group. But it was of no surprise to Bruford, who had been a fan since their earliest days.

“I played fairly easy to get,” Bruford now admits to Prog. “I kind of stuck myself in front of Robert and said, ‘I’m here.’ Yes and King Crimson had played together on the same bill [in the US in 1972], but for several months it was, ‘Not yet, Bill,’ and then eventually it was, ‘Okay, Bill, let’s do this,’ as if I had been a tomato ripening upon the vine ready to burst forth with goodness.

I was a romantic, and saw the positive gloss over potential pitfalls… I thought Robert could provide a space where I could grow and learn, and I was right

“I was thrilled to be part of it, although I’m not sure I really knew what I was getting myself into. I didn’t know Robert very well. I just jumped in and hoped for the best. I don’t mind doing that, but of course it can go wildly wrong.”

The Melody Maker gossip column The Raver from August 5, 1972 included this entry: “Bill Bruford quitting Yes was strange timing... Gigs with KC don’t exactly last, at least on present form.” Did Bruford share those sentiments in any way? “I didn’t,” he says. “I was a romantic, and saw the positive gloss over potential pitfalls. I was aware that I had done my best in Yes; it was time for a change. I thought Robert could provide a space where I could grow and learn, and I was right.”

Fripp called on another well-known player and an old friend from Bournemouth: bass guitarist and vocalist John Wetton. Bruford had seen him on TV with Family and recognised him as one of the “bass players of the moment.” Wetton had previously enquired about joining King Crimson in 1971, but bass guitarist and vocalist Boz Burrell had just been drafted in, so he joined Family instead.

“I saw the first King Crimson at The Marquee and the London College Of Printing in 1969,” Wetton told this writer in 1997. “I thought they were outstanding in that they were so different from anything else, but you knew it was quality.”

The unique element in the new line-up – as he would have been in any group – was Jamie Muir. He had recorded little aside from the self-titled album by Music Improvisation Company in 1970 with guitarist Derek Bailey and saxophonist Evan Parker, and had played in a more rock context with Pete Brown And The Battered Ornaments, Boris and Assagai, where he met keyboard player Alan Gowen. He and Gowen teamed up with guitarist Allan Holdsworth in the short-lived Sunship, and Muir was then recommended to Fripp by journalist Richard Williams.

Although Muir had been drawn to improvised music for its intricacy and detail, he felt that from a distance it tended to assume a similar kind of shape. In an interview with Aymeric Leroy in 2000 Muir said that he had wanted “to make myself more predictable” with Sunship.

He gave me one of my first and best drum lessons. At one point he stopped the proceedings and said, ‘What you’re playing is crap’

But by the time he had become a member of King Crimson in the summer of 1972, it was debatable if that statement held up. Muir had amassed an enormous percussion setup. Looking like some strange art installation, it included a standard drum kit, rattles, bird calls, car horns, chimes, bells, gongs, metal sheets, tuned drums, plastic bottles, and other hitables too numerous to detail. And at a time when to be weird was cool, press shots of Muir leaning towards the camera grinning through a waxed moustache while playing a bowed saw piqued the interest.

Rehearsals with the full line-up got underway in September 1972 at Richmond Athletic Ground clubhouse. Bruford and Wetton clicked immediately as a powerful rhythm section. The bassist recalled its potency: “What Bill and I provided was a kind of R&B rhythm section to what the ‘aerial instruments’ – Robert and David – would provide over the top, although it might have been in 13/8. We had a good grounding in Motown and jazz and blues. If you had a standard stodgy English rhythm section it wouldn’t have worked, but we played around with the beat. It was very funky in a way.”

Bruford agrees entirely. “I think John and I were very simpatico,” he says. “We used to play Herbie Hancock records – Crossings had just been released that summer – and figure out how they worked, and built this powerful unit. Robert would sometimes refer to it as ‘the flying brick wall’ – you know, ‘play with it or duck.’ Highly unflattering! But we definitely had some muscle. We weren’t a wimpy group at all.”

Muir told David Teledu from Ptolemaic Terrascope in 1991 that “Bill Bruford and I got on very well together musically, it seemed to me. He was a solid, tight, thinking studio type and I was very much into doing imaginative odd things.” But while rehearsing at Richmond, Muir gave his fellow drummer a public dressing down that practically reduced him to tears.

“Jamie was older than me and a powerful guy,” Bruford recalls. “First of all, his instrumental arsenal was about five times the size of mine and occupied most of the rehearsal space. He gave me one of my first and best drum lessons. At one point he stopped the proceedings and said, ‘What you’re playing is crap.’ And I thought what I was doing was quite good, because I had the fastest paradiddle in Sevenoaks, Kent, and being the young man that I was, I was determined to deploy it at every possible opportunity. And Muir quite quickly had seen right through that. He said, ‘What you don’t understand is that the music doesn’t exist to serve you. You exist to serve the music.’

“It was all a bit fraught, to start with,” Bruford continues. “I think part of Robert putting the band together was a bit like Miles Davis – you pick five interesting guys, lock them in a room together, and try to extract a collision of experiences from them. And if they make an album without actually killing each other first, it will at least be an interesting album.”

I was expecting there to be a lot of fiddling around and head-scratching. But they accepted what I’d written almost as if they were happy to have something they could use

Was there a rapport between the musicians? “I think there was, yes,” says Cross.” I don’t remember there being any issues. John and Bill were both kind, generous people.” He then describes how the material was worked up. “It was a democratic process: Robert had compositions, and he had fantastic ideas, and so did other people. We were lucky to get a long writing and rehearsal period – six weeks, I think. And the whole point was being yourself in that context. Sometimes we struggled with that, and sometimes it was easy, but that was what was on the table.”

King Crimson had always sought a balance between finely crafted songs and hair-raising instrumentals, and lyrics were needed for the new material. Guitarist and songwriter Richard Palmer-James had known John Wetton from school in Bournemouth, where he had briefly met Fripp, and in the late 60s they had played in the bands Tetrad and Ginger Man. He had gone on to become a founder member of Supertramp, playing guitar and writing the lyrics for their self-titled 1970 debut album.

“John played me hours of tapes from the rehearsal studio,” Palmer-James recalls. “We’d been listening to Frank Zappa’s Hot Rats with ‘Sugarcane’ Harris, and John was so thrilled to be playing with a violinist who could improvise.”

Wetton made a “vague postulation” that his friend might try to write some lyrics for King Crimson, and in the autumn of 1972, Palmer-James, who was then living in Germany, received a surprise package in the post. “It was a cassette with very rough demos of John on the piano,” he recalls. “And these first two songs were Easy Money and Book Of Saturday.

“The way I’ve always written lyrics is that I need to first have a melody line, practically for every syllable,” says Palmer-James. He set to work, but given what had happened between Fripp and Sinfield, did he receive any guidance or stipulations? “I was expecting there to be a lot of fiddling around and head-scratching,” he replies. “But they accepted what I’d written almost as if they were happy to have something they could use.”

If one person went out on a limb, the rest would support him. That was the only rule we had

It’s rarely mentioned that, with the inclusion of Moonchild, In The Court Of The Crimson King – progressive rock’s first fully realised major statement – is actually 25 per cent free improvisation. It’s an approach that’s been rarely used in conjunction with rock music, where improvisation is usually jamming, soloing at length over a riff or chord sequence. “I wasn’t much of a fan of that. Neither was Robert,” says Bruford. “And nobody wanted to be in a second-rate kind of blues group. So blues pentatonic scales were avoided in favour of a more European voice.”

When the new line-up began playing live in the autumn of 1972, their sets consisted of predominantly new material and improvisations that could last for up to half an hour. They would frequently encompass meditative, abstract passages and full-throttle groove excursions.

Violinists in rock were a rare breed at the time and Plymouth-born Cross was doubly unusual in that he was also adept at improvising. As a dance band pianist and a church organist, his father had been obliged to improvise. “He was a great improviser,” Cross says. “It was clear to me from an early age that that was part of what you did in music.”

“The reason why we were different was that we were prepared to jump off the cliff,” Wetton recalled. “Half the set was improvised and we’d receive, minutes before going on, what the set would be. We had marker points where one person would start and the rest would follow, otherwise it’s chaos. So if one person went out on a limb, the rest would support him. That was the only rule we had. Or I could start singing a song and we would go into a formal piece. Eight out of 10 times it worked great. We were telepathic, totally tuned in. It was an adventure every time and very exciting.”

On his first exposure to the new line-up, Ian MacDonald of New Musical Express was uncharacteristically gushing. He wrote: “Britain’s most enigmatic combo... produced at least half an hour of the most miraculous rock I’ve ever heard.” He also praised their collective dynamics: “Crimson aren’t so much about sound and physical impact as about improvised form, simultaneity and ESP.”

Melody Maker’s Richard Williams was also impressed: “There is nothing more exciting than hearing a new band that single-handedly and out of the blue opens up completely new musical territory.” In Melody Maker The Raver recommended readers to “look out for loony percussionist Jamie Muir and John Wetton’s world-class bass.”

Close To The Edge had more edits, more talk, more disagreement.… Larks’ Tongues. was a bit slicker, less talking, more agreement and quicker

If that sounded a tad disrespectful, Muir was clearly relishing his move from the serious world of free improv into the rock spotlight. He would prowl around his enormous percussion kit – wearing a jacket that appeared to be made from animal pelts which would have looked dapper in the Neolithic era – and when it all got too intense he might bite on a blood capsule.

The new album was to be called Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, the title thought up by Muir when asked to describe the music. “It may or may not be an actual dish available at your neighbourhood delicatessen,” Fripp has stated. “But what it means to me is something precious which is stuck, but visible. Something precious, which is encased in form.”

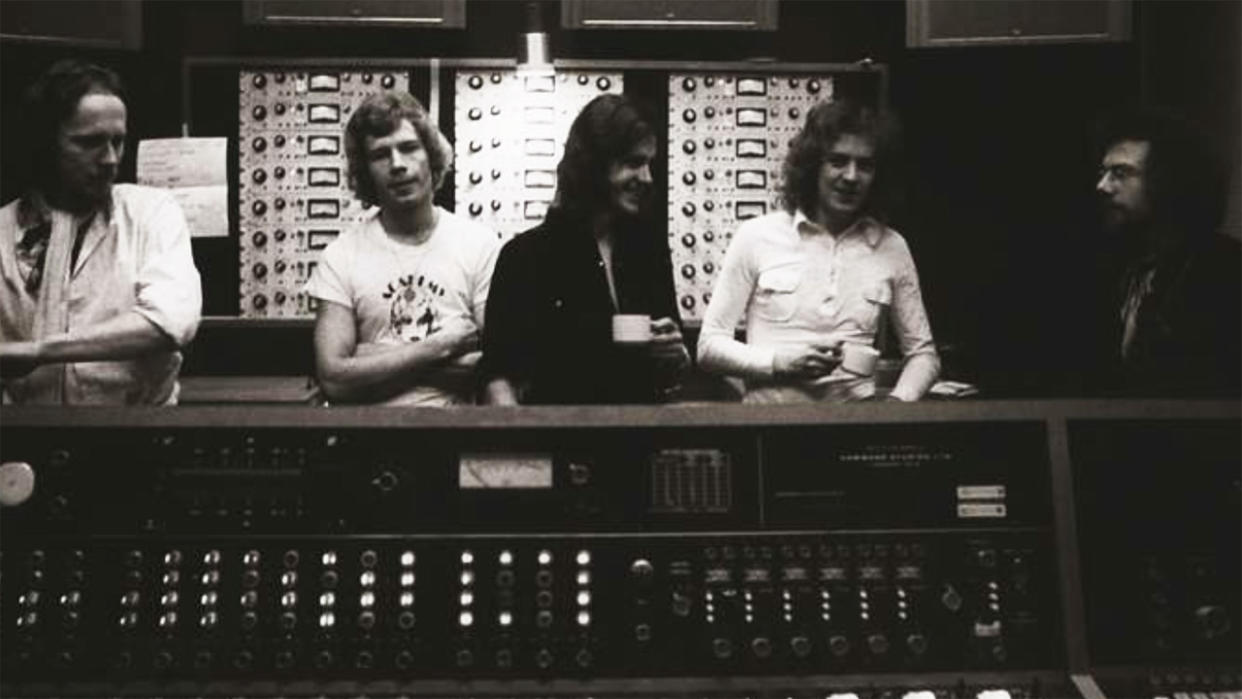

Most of the material had been played live but a lot more work had to be done in the recording sessions, which began at Command Studios, a suite of former BBC studios in Piccadilly, London in January 1973. “It was in poor shape and things kept going wrong all the time, but we squeezed in,” says Bruford. “Muir took 75 per cent of the space and everything of his was mic’d up; I was squished in a corner somewhere.”

For Bruford it was a very different experience from his last stint in the studio, the lengthy process required to record Close To The Edge with Yes. “Close To The Edge had more edits, more talk, more disagreement. On the whole Larks’ Tongues was a bit slicker, less talking, more agreement and quicker,” he says.

Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, Part One opens the album. Fripp had first presented it in part to the Islands line-up in 1971, but claims it “wasn’t recognised” by the musicians. When taken to Command, the key structural elements of the piece were in place, but it was still a work-in-progress. In its 14-minute recorded form, it became a dazzling, episodic suite.

The opening section was immediately disorienting. What was going on? It was the first and perhaps only appearance in progressive rock of the mbira, an African thumb piano, played by Muir, with a counterpoint glockenspiel line. This gives way to a shimmering curtain of metallic sounds and then, after three minutes, into an ominous staccato violin passage. This built up into an enormous drum roll that introduced a dramatic six-chord riff, an example of the “monstrous power” the percussionist had felt the band were capable of producing.

David and Jamie play a small tune that they got together on the spot. And I’ve always seen that, in a way, as the lark’s tongue in the aspic

The second time around this build-up includes what sound like two-note brass lines, which are actually Muir’s car horns. Then, in Bruford’s words, there’s “a fast-moving 7/8 passage”, with himself and Muir striking sparks off each other against Fripp’s angular and convoluted guitar-picking. After that came a new improvised section with Wetton on wah-wah bass, Fripp’s frantic chord work, and Muir running across his percussion setup at breathtaking speed.

In the Larks’ Tongues In Aspic (The Complete Recordings) 2012 box set, there’s a CD of studio run-throughs. At the start, Muir can be heard asking the engineer Nick Ryan, “Nick, is it possible to have the baking tin louder in my cans?” It’s unlikely that Ryan would have ever received such a request before. Muir’s kit, Bruford notes, was “prepared” by chains being placed across the tom-toms and baking trays attached to the bass drum. “He instantly turned it into a metallic beast, clattery and indistinct,” he says. “And it always sounded to me like traffic chaos. The section with Jamie going nuts was terrific. I remember it going down and I’m getting a little chill up my spine thinking of it now. It’s exciting stuff.”

What follows is the intermezzo or “water section,” as Muir referred to it: a subdued duet between Cross’ violin and his own zither played with hammered dulcimer mallets, delicately and at great speed, yielding harp-like glissandi. Bruford picks out a particular detail in this section: “David and Jamie play a small tune that they got together on the spot. And I’ve always seen that, in a way, as the lark’s tongue in the aspic. A little jewel, a perfect moment of stillness right in the middle of all this mayhem.”

“The album is absolutely precious in terms of the space between notes and the quiet passages, and I was very proud of what I managed to achieve within it,” says Cross. His violin solo reminds Bruford of the English pastoralia of Ralph Vaughan Williams – The Lark’s Tongue Ascending, if you will – and there are also motifs reminiscent in mood of 20th-century Hungarian composer Béla Bartók’s string quartets. Was he a direct influence? “Yes, very much,” Cross confirms, “particularly his string quartets. I listened to them as a teenager alongside Rubber Soul. I was fascinated by the scales that he used, and also the rhythms.”

The ominous staccato theme from the start of the piece re-emerges, this time played by Fripp on guitar over which Cross plays a “running violin line.” And there is a discernible vocal presence in the background. “It was a recording of a radio programme Jamie brought in, which featured a judge passing a death sentence,” says Cross. “The words I remember are, ‘You will be taken from this place and hanged by the neck until you are dead’, and the word ‘dead’ coincided with the first note of the final section.”

Another drum roll starts, but rather than ushering in more massive power chords, it turns into a melodic coda, with Wetton’s bass to the fore, over a babel of barely intelligible voices. These are Bruford, Muir and Cross reading out passages from magazines.

All the lyrics I wrote… It’s like a holographic picture of an affair or a sexual encounter, before, during, and afterwards

There was nothing like Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, Part One at the time and 50 years on it still sounds unique. After this mini epic comes three further songs. The concise, subdued Book Of Saturday offers light relief. It’s played in trio format with Wetton’s warm baritone backed by delicious interplay between Fripp and Cross, including an overdub of backwards guitar. Palmer-James’ lyrics, which detail a relationship, include the striking lines: ‘As the cavalry of despair/ Takes a stand in the lady’s hair.’

“I visited them in Command Studios when they were recording the album,” says Palmer-James. “As a sort of conversational gambit I said I was worried that that line was over the top. And Fripp said, ‘No, it’s one of my favourites; I love it.’

“All the lyrics I wrote for King Crimson were quite specific,” he continues. “It’s like a holographic picture of an affair or a sexual encounter, before, during, and afterwards. So they’re the elements of hoping that it’s going to work, enjoying it while it’s working and regretting that it doesn’t work, all wrapped up in this mêlée of words.”

Exiles harks back to King Crimson’s earliest days both style-wise and specifically, as it uses a theme from an unreleased composition, Mantra, which was played by the first line-up. But it’s lighter, fresher and less grandiose than the Mellotron ballads of yore. Bruford concentrates on a crisp snare figure and Fripp plays acoustic and electric guitar. Cross came up with the main violin theme in an early rehearsal and plays uncredited flute and Wetton some uncredited piano.

“It has a wonderful melody,” says Palmer-James. His poignant lyrics were written when he’d moved to Germany and was looking back nostalgically on the Bournemouth he’d left behind, with the lines, sung by Wetton, ‘My home was a place by the sand/Cliffs, and a military band/Blew an air of normality.’ During the introduction, Muir evokes currents of wind and water from, of all things, tape-manipulated recordings of glass rods rubbed with an oily cloth. There are also sounds like distant seagull cries, before the Mellotron looms up out of the sea mist. “I wish that I’d asked John, when I had the chance, about Jamie’s scene-setting on Exiles. I think he must have told him that it’s about Bournemouth,” says Palmer-James.

Musically, Easy Money is a Fripp and Wetton composition and, according to Palmer-James, is, “A tale of a guy and his moll, as they used to say, and she has a talent for choosing winners at the races, which he makes shameless use of – he doesn’t seem to mind getting ripped off by this character. It’s sort of burlesque.”

I played Larks’ Two for Bill and John right at the beginning and they didn’t hear it. I re-presented it at rehearsals… they picked up on it and ran with it

It’s also the album’s rockiest track, a prime example of Bruford and Wetton’s subtle funkiness, with Muir sloshing his hands in buckets of mud to accentuate the tolling rhythm of the introduction. He scrunches up paper and at one point dramatically unrolls a reel of tape. Fripp plays some corrosive guitar with a dry, buzzing tone.

It ends with the sound of a Laughing Bag toy and then we are suddenly out into the windswept expanse of The Talking Drum, with Muir whirling a bullroarer, a sound akin to a giant mosquito. This begins a 14-plus-minute section of instrumental music that neatly balances the album’s structure. Muir plays a speedy free-form hand drum solo before settling on a rhythm, but is soon drowned out by Bruford and Wetton locking into a 4/4 rhythm with a bass line that see-saws around two chords with Cross extemporising and Fripp’s guitar buzzing malevolently as it builds in intensity. Bruford has a confession to make. “The Talking Drum is terrific, very exciting, but unfortunately it slows up on the album – unforgivable! That’s quite a problem with young drummers. As they get louder they tend to get slower, which is my fault entirely. Sorry, guys. I didn’t realise that at the time!”

Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, Part Two is neither like Part One nor like anything else in rock music at the time. “I played Larks’ Two for Bill and John right at the beginning and they didn’t hear it,” says Fripp told this writer in 2022, “and it wasn’t until I re-presented it at rehearsals at Richmond in the Athletic Club, that they picked up on it and ran with it.”

It was the first incarnation of Fripp’s stark, riff-based compositions constructed from motifs that typically involve a small number of chords in insistent, rhythmically intricate combinations. Many progressive rock bands in the 70s were influenced by – or appropriated – romantic classical music, but the opening riff here sounds like the jagged cellos in The Augurs Of Spring section of Stravinsky’s The Rite Of Spring.

“I always thought that Robert was more inclined to say that it was Bartók who inspired him,” Cross recalls. “As a violin player, I play it much more like Stravinsky, so I tend to hear those accents as quite sharp, quite strong, with lots of attack. But listening to the record, they’re not played like that by John and Robert. It’s a bit smoother and more subtle than I used to hear it.”

Towards the end of the composition, Cross’ violin solo rears up spectacularly out of that formal grid pattern. “What the 1973 David is saying to me is that’s the only way I could get heard against the strength of that very powerful heavy riff,” Cross says. “I was interested in using slides, so as the rest are playing very clear notes, you’ve got something where they’ll hear what you’re playing. Lots of slides and attack, and short notes.”

If your version of rock music is sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, or three chords and the truth, there isn’t an awful lot of that on Larks’ Tongues In Aspic

And as the track and the album reaches its conclusion Muir signs off with a thrilling percussive onslaught as if he is trying to derail the piece’s inexorable formal logic by sheer force. “That’s exactly what’s going on there,” says Cross. “And that’s the battle. Can we have complete freedom or do we have to follow the rules?”

The striking cover image for Larks’ Tongues In Aspic was chosen by Fripp: “The sun and moon cover is from a series of tantric symbols,” he says. “I believe the artist was Peter Douglas of Tantra Designs. The symbol itself addresses the union of opposites.”

It’s also a visual key to something that Bruford hears in the music. “The King Crimson on this album could somehow straddle and counterbalance musical opposites,” he says. “It could be one thing one moment, and another in another moment: a pastoral idyll over here and then traffic chaos over there.

“Myself and John, I think, were balanced by David and Robert,” he muses. “On the whole, we were the muscular side of the group, and perhaps they were the more esoteric. And you had the juxtaposition of Muir’s kind of folkloric instruments with the electric barbarity of the post-Stravinsky heavy riffage. Balancing these things – the band seemed to be able to do that on a dime, which was really nice. And nobody constructed that; it was just something we were able to do, I think, really well.”

Bruford also identifies both the album’s “wide textural range” of instrumental combinations and its wide dynamic range. “The idea of getting from tiny, tiny ‘ppp’ to ‘fff’ in two or three minutes is very exciting and a lot of that went on, but it didn’t help much with the record company.”

He recalls being in Los Angeles in a limo with a senior vice president of Atlantic Records. The company was releasing the album in the States, but he knew little about the group. “The voice on the car radio announced, ‘Here it is, the great new album from King Crimson.’ They played Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, Part One and the first three minutes were quieter than the road noise coming from the wheels of the car. He looked at me, thinking, ‘Is this what Atlantic Records has just bought?’ And I’m thinking, ‘Oh, God, please come on to the riff, something that sounds like rock music.’ Of course, if your version of rock music is sex, drugs and rock’n’roll, or three chords and the truth, there isn’t an awful lot of that on Larks’ Tongues In Aspic.”

The diversity of styles was such that you really had to pay attention… We didn’t know what we had to listen for so we had to listen to everything with really quite extraordinary results

Even listening at home its dynamic range sounds exaggerated at times. Cross recalls that the whole band were involved in the production and mixing of the record. “I think it was a very brave decision, but I think it was wrong – I’ve got to attribute this to Robert now, because there’s something wrong with it,” he jokes. “I certainly supported the decision at the time, but now I think the beginning of Part One is too quiet; the violin solo, the intermezzo is too quiet; the vocal on Easy Money when it comes in is too quiet.”

Fripp has his reservations about the album for different reasons: “Larks’ Tongues In Aspic came close to being a defining album, but the sound wasn’t good, because it was made at Command Studios and the band hadn’t had enough experience playing it in,” he says. “So it was a very strong beginning, but it didn’t have the satisfaction for me of either In The Court... or Red, because it didn’t sound as good. It wasn’t as fully realised.”

“I don’t think they liked the sound of the finished product,” says Palmer-James. “But I think it’s got something special. It’s rather dry, but that seems to fit the overall vibe.”

Athough the album remains a fan favourite, it received a mixed bag of reviews. Richard Williams of Melody Maker saw it ultimately as a failure and read its balancing of opposites within a wide stylistic remit as an “acceptance of compromise” and that while it had some “excellent moments,” he felt that Fripp had chosen “to tread water and settle for the merely adequate.” In NME, Ian MacDonald qualified his enthusiasm by wondering if the listener would, “See the album as the group do – a sequence of vivid contrasts of design and sound-quality – or, like me, hear a still slightly uneasy meeting of two extremes.”

The album peaked at No.20 in the UK and at No.61 in the US. Tour dates had been booked but even before it was released the enigmatic Muir had left. Despite his crucial role in the group he was frustrated by the way his approach to improvisation came across with a rock band both live and in the studio. And even more importantly, he was following his Buddhist calling. “I went up to a Tibetan monastery in Scotland,” he told Ptolemaic Terrascope. “I didn’t feel too happy about letting people down, but this was something I had to do or else it would have been a source of deep regret for the rest of my life.”

The four-piece line-up went on to make two more remarkable albums – the more astringent Starless And Bible Black and the carbon-dark near metal of Red, although Cross left before the latter was completed.

It has secrets that can be revealed, depending on how you change as a human being… how I hear it now is not at all how I heard it the day after we recorded it

And, again, only the most gifted seer could have possibly predicted that Fripp would choose to disband this extraordinary group 18 months after Larks’ Tongues In Aspic and just before Red was released. And also that King Crimson’s story would pick up again many times and continue to the present day. As it stands the group have ceased live activities but have not officially broken up.

Listening back to the album recently, Cross was struck by the sensitivity of the playing and “the taste and care over the phrasing.” He also discerned “a rare kind of listening” in the musicians. “When you’re familiar with a style, you get to listen out for certain things, but with Larks’ Tongues the diversity of styles was such that you really had to pay attention all the time. We didn’t know what we had to listen for so we had to listen to everything with really quite extraordinary results.”

“What I really like about the album is you can approach it on all kinds of different levels,” says Bruford. “I was looking at some reviews online and fell across this: ‘One of the greatest prog albums ever. It sparks, then it’s spooky, then it rocks hard, then it’s mellow. Then it’s funky, then it’s epic and finally it crashes and blows up.’ I think that’s lovely and you could approach it in that way or go seriously deep if you want to, as with musicologist Andrew Keeling’s book [Musical Guide To Larks’ Tongues In Aspic By King Crimson].

“It has secrets that can be revealed, depending on how you change as a human being,” he continues. “So how I hear it now is not at all how I heard it the day after we recorded it. Now I’m deeper into the album, and I hear, ‘Ah, that’s what he was talking about’; and ‘That’s why he played that’; and ‘Oh, that’s what we mean about opposites,’ and so on. Has it got plenty of meat to come back to in 50 years’ time? I think that’s the key to a good album.”