“He’s playing songs he didn’t even like!” Roger Hodgson’s Supertramp beef with Rick Davies

On leaving Supertramp in 1983, Roger Hodgson made a deal: he’d keep his songs, Rick Davies would keep the name. But by 2010 the deal had been broken. That year, Hodgson told Prog he felt betrayed, and said it had scuppered the chances of a 21st-century reunion – even though he’d offered to return.

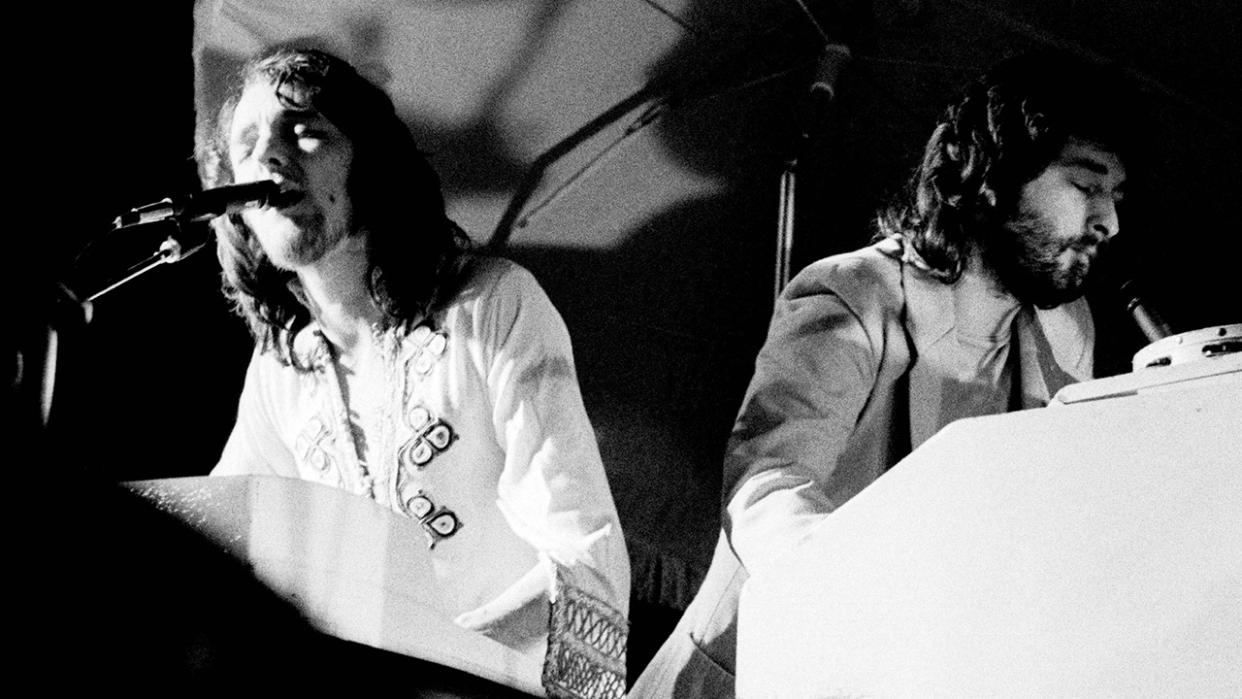

When Supertramp played at the 02 Arena in October 2010, there was one member of the band conspicuous by his absence: Roger Hodgson. Considering that, for many, his distinctive tenor voice and the songs that he wrote for the prog-pop group – Dreamer, Give A Little Bit, The Logical Song, Breakfast In America, Take The Long Way Home and It’s Raining Again – are what made Supertramp so special, it was a bit like going to see The Beatles without John Lennon or Paul McCartney. Sure, you still had present and correct the band’s other songwriter, Rick Davies – the George Harrison of the piece, responsible for such classics as Bloody Well Right, Goodbye Stranger and Gone Hollywood – and there were the ’Tramp’s twin Ringos, John Helliwell and Bob Siebenberg, on, respectively, saxophone and drums. But their mainman, their driving force, was missing, even though many of his songs were being sung. And he wasn’t very happy about it.

Why? Because the agreement made between Hodgson and Davies in 1983 after the ...Famous Last Words... album, when the former decided to quit Supertramp, was that Davies would keep the band name while he, Hodgson, would keep the songs he wrote for the band for his solo purposes. For the Davies-led version of Supertramp, Hodgson’s compositions would, it was decreed, be out of bounds.

It was a verbal contract – one apparently witnessed by the other members of Supertramp – that Davies stuck to for five years; but since the late 80s he has irregularly toured under the guise of Supertramp for concerts that substantially comprise Hodgson material.

Asked whether it was difficult watching the band – whose stratospheric success, including the 20-million-selling Breakfast In America, were in large part due to his input – carry on without him after he left, he replies: “Well, it wasn’t difficult initially because Rick upheld his agreement, which was that Supertramp would become a vehicle for him and his music and I would start a career with my songs and my voice. That’s the only reason I agreed to give him the name.

“The difficult part came when he broke that agreement and started playing my songs five years later. That hurt very deeply. I felt betrayed.” It was this betrayal, Hodgson explains, that has got in the way of a reunion with Davies over the years. “If he hadn’t done that,” he says, “it’s very likely that we’d have done something together at some point.”

Have they been in contact? “Many times. I’ve spoken to him, and even with what’s happened we’ve talked about working together, but it seems to go from bad to worse.”

The 02 show was, for Hodgson, the straw that broke the camel’s back. “He advertised the whole tour with my songs and played seven of them, which was basically him saying, ‘Fuck you, Hodgson, I’m going to do what I want.’ And that doesn’t feel good.”

What is Davies’ response on the occasions that he has broached the subject with him? “He’s very sheepish and says he’s basically getting a lot of pressure from everyone to do the songs. I can understand the pressure because me and my songs were such a huge part of Supertramp.”

We kept the writing credits as Hodgson-Davies, which wasn’t the smartest move on my part because most of my songs were the hits

Hodgson the Beatlemaniac acknowledges that he and Davies the blues buff got on like a house on fire and had just the right chemistry when they met at the auditions to join Supertramp way back in 1969. The former was a 19-year-old ex-public schoolboy and the latter an older, more bluff working-class type; nevertheless, there were, Hodgson reflects, similarities. “We were both loners,” he decides. “We were close in the early days, but as time went on, we grew apart.”

In a way, it was the songs that pushed the two writers apart; that and their different attitudes towards success and the momentum that was required to sustain it. “We were like Lennon and McCartney in that we wrote separately, even though we kept the writing credits as Hodgson-Davies; which wasn’t the smartest move on my part, because most of my songs were the hits,” says Hodgson, who had amassed about 30-35 tunes while still at home as a teenager in Oxford.

Supertramp’s first two albums – the self-titled debut (1970) and Indelibly Stamped (1971) – bombed commercially, so it wasn’t an issue; but by the time of 1974’s breakthrough set Crime Of The Century, it perhaps started to rankle that Hodgson was pulling more weight than anyone else.

“I could see the potential of the band,” he says, adding that he found an ally in engineer and unofficial sixth member Russel Pope. “Like me, he’d been affected by The Beatles and seen how they had changed our lives and helped changed the world. We were interested to see how Supertramp could do the same. He and I were driven and had a similar passion for that.

“We weren’t just in the band to be successful and make some money; we wanted to make a contribution and do something really special. I really think I was the main driving force in the band, and Russel was my able partner. We were just relentless; we wouldn’t let it go until we’d taken it as far as we could in every direction – in the studio or live on stage.”

Even when I was writing songs about my spiritual quest, the band never really asked what they were about

Hodgson has always felt apart from the rest of Supertramp. Whether it was during their early heyday with Crime... (and the less successful follow-up, 1975’s Crisis? What Crisis?), their mid-period US breakthrough with 1977’s Even In The Quietest Moments... and their commercial pomp with 1979’s Breakfast In America, he felt “lonely and alienated.”

It was he alone who went vegetarian when he was 21, and “the rest of the band thought I was nuts,” and he who began to pursue a more spiritual existence after the band decamped to the US for the recording of Quietest Moments... and Breakfast. “I was the only one with any interest in spiritual answers,” he argues. “Even when I was writing songs about my spiritual quest, such as Babajil, the band never really asked what they were about, so it was lonely in that sense.”

He was also the one who felt most at home on the West Coast (apart, of course, from the surfing Californian drummer Siebenberg). “I thought I’d died and gone to Heaven,” he recalls. “There were health food stores on every corner, yoga facilities and meditation classes... Everything I’d been yearning for, I found. It was also a way for me to escape my English roots. I needed to redefine myself. It was like a breath of fresh air.”

Hodgson considers that he has “always been out of step with the times,” and although he baulks at the idea of himself as an unreconstructed hippie, he does admit that “the late 60s and early 70s had a big impact on me – I rode the wave of it. There was a huge shift in consciousness. Our imaginations were set free.”

Surprisingly – not least because of the way the band ended – he believes that “one of the special things about Supertramp was that we all tolerated each other even though we were all very different.” At their height there was a “wonderful feeling in the organisation that people would remark on. We were a very good-feeling band. No one was crazy, no one was out of control; we weren’t on the rampage like a lot of bands, and we basically toured the world putting out a lot of good energy. It was like a travelling community, or a large family.”

He said, ‘I just want to make music with dignity’ …what he’s been doing is anything but making music with dignity

Unfortunately, halfway through touring Breakfast... around the world, “the fun went out of it” and the family began to fall apart. “That’s when people started thinking independently,” says Hodgson, who struggled to “reconcile the business aspect of the music with the original passion that went into it.” He also wanted to devote more time to his two young children and the wife whom he’d met on a commune in the States, so he moved up to Northern California and “built a home for my family – I left the band and didn’t tour for 16 years.”

Between his departure from Supertramp in 1983 and the turn of the century, Hodgson released three studio albums: 1984’s well-received In The Eye Of The Storm, 1987’s Hai Hai and 2000’s Open The Door. It was around the release of Hai Hai that he broke his wrists in a fall at his home, which put paid to any touring plans he may have had. Besides, within a year, Davies’ use of his songs for the ongoing Supertramp added to a growing dissatisfaction with the industry, and he was happy to keep away.

To this day he remembers the promise Davies made to him in 1983 – and it still hurts. “He said, ‘I realise the band isn’t going to be as successful in the future, but I just want to make music with dignity.’ Those were his exact words. And what he’s been doing these last three or four tours is anything but making music with dignity in my book. It’s sad that the artist in him has sold out.”

Doesn’t Hodgson, with his spiritual beliefs, accept that the remaining members should be allowed to play his songs for the sake of the fans? Not necessarily. “That’s a pie-in-the-sky spirituality that’s not based in reality at all,” he says. “I understand totally that when fans think of Supertramp they think of The Logical Song and Breakfast In America. But it’s not a question of spirituality, it’s a question of right or wrong.

“If we hadn’t had that agreement and parted company in the way we did, we wouldn’t be having this conversation. I wouldn’t mind, but [Davies] is playing songs he didn’t even like at the time!”

In spite of it all, Hodgson insists he would have appeared at the recent reunion shows; it was Davies who rejected him. “I sent a message to him saying, ‘Obviously thousands of fans would love to see the two of us onstage together and I would be willing to show up and do a few special shows with you as and when my schedule permits’ – because I was on tour, too – but the offer was rebuffed in no uncertain terms. He gave a very strange reason: it would only benefit me, not him. I couldn’t understand that.”

Was he afraid that you would steal the limelight? “I think that’s it.”

I’ve put my heart and passion into sharing my songs. I’m having more fun now even than I did with Supertramp

While we wait for hell to freeze over, Hodgson is having the time of his life, touring his songs with a great backing band, and pondering the recording of the numerous compositions he’s amassed over the last decade – 60 at last count. Mainly, he’s relishing the effect his music has on fans.

“I’ve been touring for the last six or seven years, and I’ve put my heart and passion into sharing my songs,” he says. “I’m having more fun now even than I did with Supertramp. The fans are coming to my shows and loving them.”

Does he consider it ironic or that music borne out of emotional turbulence and internecine tension should generate such good feelings? “I don’t think that matters,” he says. “Artists are not perfect beings, although their art represents the best part of them. It’s the art bit that’s important to me.”