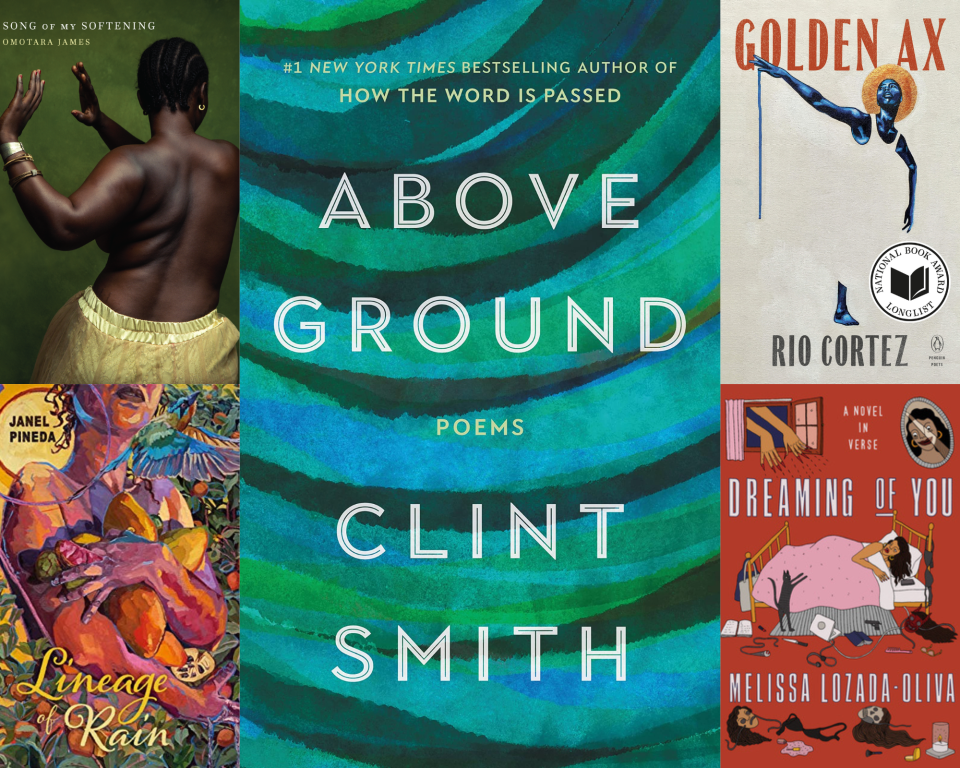

'Poetry offers us a powerful space': Janel Pineda, Clint Smith, on magic of poetry

Purchases you make through our links may earn us and our publishing partners a commission.

Janel Pineda, a Los Angeles-based poet and educator, has little in common with Walt Whitman and William Shakespeare.

But growing up, the 26-year-old'sview of poetry was heavily influenced by those two men, "both of whom were writers who have experiences that I didn't identify with as a working-class Salvadoran girl growing up in LA," says Pineda. Poetry felt more reassuring to the current UCLA Ph.D. candidate because of writers of color and how they "were using poetry to articulate their experiences and their politic."

"It made me feel seen and it made me feel like poetry could be something else aside from what I had been taught," the author of "Lineage of Rain" adds. "Poetry offers us a powerful space in which to imagine the world that we want to see and to more clearly understand the world that we live in."

"Lineage of Rain" at Amazon for $10

"Lineage of Rain" at Bookshop for $9

Cultivating that curiosity starts in the classroom. Yet, it's the same space where we're often taught to look at different forms of art as black or white, right or wrong.

"Sometimes we're taught to read poetry as if it's a code that we have to unlock or that it's a puzzle or a geometric proof with a specific answer," says Clint Smith, author of new poetry collection "Above Ground" and writer for The Atlantic. "I don't think that that's what poems are or should be."

'A chilling effect': What happens to our culture when books are banned

Poetry is what you make it

To Smith, it doesn't matter what a poem was "supposed to be when I wrote it. What matters is what you think it means (because) when you create art and then release it out to the world, it doesn't belong to you anymore."

The beauty of a poem can lie in not knowing. "It's important to challenge myself to read things that I quote-unquote 'don't get,' " says Traci Thomas, host of the podcast and one-stop-shop for everything books, "The Stacks." "I'm obsessed with this idea of, 'Did I get it? Did I get it right?' And it's a really good exercise for me to not know. The poet is not going to come in and be like, 'Correct! A+ for you.' And that's a valuable skill set for me, to be frustrated or to be unsure."

When you do find meaning in it, though, poetry can be restorative, revolutionary and redemptive.

"It can be really empowering to see the poetry in the everyday," Pineda says. "By that, I mean poetry teaches me awareness. It teaches me to slow down and pay attention to the small details of life and by allowing yourself to tap into that sensibility … there's so much, there's a world of possibility readers can access by engaging with the world through a poetic lens."

Pineda and Smith's poetry is also a way for them to reach their younger selves – they're creating the type of poetry they wanted to read.

"There are all sorts of ways to be a poet," Smith says. "But I do always try to write the poems that a younger version of me would want to read. In many ways, that's my North Star."

A 'renaissance' is upon us: Interest in poetry on the rise after year of pandemic, chaos

Reading poetry can feel intimidating, but it's more accessible than you think

As transformative as poetry can be, it can also feel intimidating. But it's more accessible than you think – take it from the poets themselves.

"You can sit down for a couple of hours and take in a poetry collection from cover to cover in a way that a novel might demand more time," Pineda says. "The form of poetry is accessible even just in the time that it would take to read it."

Author Rio Cortez, whose debut poetry collection "Golden Ax" was longlisted for the 2022 National Book Award for poetry, adds poetry often gets "a bad rep for being inaccessible because it doesn't always tell a story in a linear way."

"It relies on its reader to use different tools that we don't always use when we're consuming stories, like your intuition and feeling(s)," she says. "Then some poems are so opaque that it's hard to really glean what they're about at all and they're really just kind of showing language and what language can do."

For Thomas, listening to poets talk about their work helps her as a reader and "when I'm working through their work because it helps it make sense." And for people who are "nervous about poetry or feel intimidated," Thomas wants to remind readers that it's likely "everyone (else) feels that way too."

'Promises of Gold': How José Olivarez illuminates the mundane, makes poetry accessible with his second collection

Summer is the perfect time for poetry

Nothing beats spending time with a good book beachside, in the forest or at a park during the summer months.

"Summer is a good time to have a sad-girl moment with poetry," says Melissa Lozada-Oliva, author of "Dreaming of You: A Novel in Verse." "You're away from friends and maybe family, and I feel like when I'm reading a book of poetry on the beach or something, that's when I'm like, 'Wow.' It's a nice break."

Cortez also loves it for summer reading or "when people have busy lives and they want to share (poems) with their friends or family that moves them … I think it's a great form of writing to share."

Thomas, on the other hand, is a strong believer that a summer read is "any book that you read in the summertime." To her, reading is reading.

"People put so much pressure on their reading, even as adults … about what they should be reading at any given time or any given place and I'm so wholeheartedly against that," she adds. "So few people read in general (and) many people might only read one book a year and if they decide to read that book in the summer then it should be whatever book they really want to read."

But if reading poetry is a muscle that readers want to exercise, "you can read one or two poems throughout the course of the summer … that's what's nice about poetry, too, it can be just a bite-size, little thing." (In 2017, poet Nicole Sealey started the #SealeyChallenge: read a book of poems each day for the month of August.)

We encourage you: Why you should read these 31 banned books now

At its best, poetry should evoke emotion

If there's a line that speaks to you when reading poetry – hold on to that feeling. "You don't have to figure out what the poet meant for it to be because that's what it meant to you, and that's what matters," Smith says.

Cortez and Lozada-Oliva recall the moment poetry marked them growing up. For Cortez, it was the 1993 John Singleton film "Poetic Justice." "It was a big catalyst for me wanting to write poetry," Cortez says.

And Lozada-Oliva remembers reading Sonya Sones' novel in verse "What My Mother Doesn't Know." She says, "I remember being like, 'Wow this is so fun to read and so emotional. Why am I having all these feelings?'"

That was eye-opening for Cortez as a kid. "I understood that language could tell stories and create visual images, but I didn't know it could change the way you feel," she says. "That felt really powerful to me."

But, why?: Banned book attempts hit record high in 2022, nearly double last year, says library org

"Poetry is so fueled by feeling and beauty and I feel people forget that," Lozada-Oliva adds.

It's the tumultuous times we're living in – an ongoing pandemic, ecological disaster and political upheaval – that mobilize young writers to write powerful poetry in order to help others make sense of their world, and their feelings.

"Poetry speaks directly to the language of my soul," Cortez says. "Especially in moments of grief and joy and crisis, I've turned to poetry because there are some universal truths there and it's a way to feel connected to humanity … there's just such a value in every single word."

"Lineage of Rain" at Amazon for $10

"Lineage of Rain" at Bookshop for $9

A must-read interview: 'Woman Without Shame' and poet Sandra Cisneros talks sexual desires and feeling 'empowered in my 60s'

If you're looking for more poets to read:

Rio Crotez's current faves:

Ross Gay

Janel Pineda:

Cynthia Guardado

Donika Kelly

Ada Limón

Melissa Lozada-Oliva:

Franny Choi

Terrance Hayes

Dorothea Lasky

Ariana Reines

Clint Smith:

Hanif Abdurraqib

Elizabeth Acevedo

Eve Ewing

Safia Elhillo

Nate Marshall

Traci Thomas:

E.E. Cummings

Nikki Giovanni

Saeed Jones

Jose Olivarez

Jasmine Mans

Nate Marshall

Clint Smith

'Can’t take these freedoms for granted': Authors of most banned books in the U.S. speak up

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Poets Clint Smith, more break down the genre, its accessibility