“This was the Prime Minister we were dealing with, and we were very naughty boys:" a story of The Move, acid, axes and a 55-year-old political scandal

Alexandra Palace, April 29, 1967. The dawn of the Summer of Love. It’s the afternoon of the infamous 14-Hour Technicolor Dream – London’s answer to the American Merry Pranksters-inspired Acid Tests. Roy Wood, guitarist and main songwriter with British pop band The Move, has just done a soundcheck, and is walking off stage when he bumps into a familiar face.

“I was strolling down the big hall, making my way back to the dressing rooms,” Wood recalls. “The place was virtually empty, when who should be coming towards me but John Lennon with another bloke. John was wearing his short Afghan coat with the little badges on it. I thought, bloody hell, this is unreal. I’d never met him, never come across any of The Beatles at that stage, but he was one of my favourite people. As he approached me he suddenly stopped and, like a soldier, he saluted me. So I saluted him back, and he walks on. Then he turns around and says: ‘Nice one, man.’ Cheers, John. Ta very much. I was delighted that he knew who I was.”

Lennon, accompanied by Indica Gallery owner John Dunbar, hadn’t come to see Roy, of course. He’d come to see an obscure Japanese performance artist called Yoko Ono (not yet his girlfriend), who would perform on a bill that included headliners Pink Floyd.

Fresh from a session for the song Magical Mystery Tour, Lennon had dropped a tab of acid that very morning. Roy Wood hadn’t. He had other things buzzing round his mind. The Move’s second single (the follow-up to Night Of Fear), the breezy, psychedelic Flowers In The Rain, was about to establish the Birmingham band nationally. Meanwhile, the master tapes of 10 songs destined for their debut album had recently been stolen from their agent’s car on Denmark Street (aka Tin Pan Alley) by a construction worker called Fred Higgins. At least that’s what The Move’s flamboyant manager, Tony Secunda, told the music papers.

The Move were Secunda’s plaything, to an extent. Much more so than his previous act, the relatively straightforward Moody Blues. The 26-year-old, public school-educated Secunda was cut from similar cloth to Brain Epstein, Andrew Loog Oldham and Kit Lambert, respectively the managers of The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and The Who – except that his tailor seemed to specialise in suits for self-styled hard-nuts. Secunda was actually a most genial chap – when he wasn’t decking concert-hall managers who refused to pay up, or putting the frighteners on anyone who crossed his path, tricks he’d learnt as a former Merchant Navy man and wrestling promoter.

Once he’d heard The Move, after they turned up at his offices unannounced – following David Bowie’s recommendation that they get out of Brum and hit the Smoke – he immediately saw their rowdy potential. He got them into sharp gangster threads, with heavy Crombie coats, dark leather gloves and walking canes so that they resembled a gang of gentleman thugs. He pulled fantastic stunts with the press. Like arranging for the band to sign a supposed Deram recording contract written in elaborate script on the back of topless glamour model Liz Wilson. But he cared deeply about his charges. “Without a doubt it was The Beatles, the Stones and The Move, in England… in that order,” he’d say – neatly consigning The Who, Small Faces and The Kinks to the status of also-rans.

Move drummer Bev Bevan (later with ELO) recalls: “He had such incredible self-confidence, we were swept off our feet. We were green lads from Birmingham, and he took us shopping in Carnaby Street and immediately changed our image.

“A stunt with a fake H-bomb was very funny. We went through the streets of Manchester hoping to get arrested. We were tramping up and down for two hours with this wretched bomb and nobody took a blind bit of notice. Eventually a copper told us to move on. A photographer took a picture and the papers said we’d been arrested making an anti-Vietnam protest.”

Secunda says he christened his charges The Move because the name had a simple ring, like The Who. Others say Wood came up with the name because the band members had all moved out of other groups. What is certain is that Secunda got them regular gigs at the Marquee club in London, encouraging them to drop their fluffy bouffants and college-boy scarves.

With former Danny King And The Mayfairs man Tevor Burton also brought in on guitar, The Move had a contemporary Mod look and plenty of sex appeal – Burton and bassist Ace Kefford being popular with the ladies – but their sound was in need of modernising. Secunda persuaded them to replace a live set based on the rock’n’roll and R&B covers, and to embrace a far more musically original and theatrical approach.

Wood: “I was 17 when The Move started to get it together. Once we’d been told to write our own songs it was weird, because there was nobody to follow. We made it up as we went along, although we liked a lot of the new American music. But when I was writing on my own I didn’t follow a trend and I didn’t care about fashion. That was the secret.”

In 1966, they started playing Thurday nights at the Marquee “taking over from The Who. We used to get pretty much the same audience every week, so we couldn’t repeat the same show and we learnt a lot. I had a spot during the middle of the set, the others would walk off and leave me alone. That’s where I started inventing instruments, to amuse myself, really.

"I came up with the riff for I Can Hear The Grass Grow during that solo slot. I put together a five-string guitar with bass strings and sitar strings and fed it through a pedal [and his trusty Binson Echorecs]. This was before Jimmy Page and Pink Floyd were doing that stuff. I also invented the ‘banjar’ – a banjo/sitar with the skin off the front. I was listening to a lot of Chinese music then. Oh yeah, I was also the first person to play a guitar with a violin bow. Jimmy Page came along one night and saw me doing that."

Having been very shy as a lad, Roy Wood was beginning to flourish. He adopted increasingly bizarre stage costumes, culminating in a full Crusader’s outfit. And, at Secunda’s suggestion, he dusted off the notebooks full of songs he’d written as a younger teenager (some of these can be heard freshened up on his 2011 two-CD collection, Music Book.)

“The early songs I wrote at school or college or when I was in Mike Sheridan’s Lot were never really taken seriously. I didn’t think people were interested in ’em. I was writing fairy stories for adults, things with a nasty twist. I didn’t have a clue what do with them so I saved them in folders, and then started producing them for lyrics when I was encouraged to do so in the Move. It was quite useful,” he says with typical self-effacement, “because they gave us a head start.”

Some of these songs seemed to be set in a mythical mental institution and had a macabre, Lennon-esque appeal. Disturbance (the B-side of Night Of Fear) was a case in point, with Secunda providing hideous screaming, while even the apparently benign I Can Hear The Grass Grow, or the jaunty Here We Go Round The Lemon Tree were tinged with lunacy.

Because of their musical ability the Move slotted into the new psychedelia so easily that it would be tempting to assume they were permanently stoned, but, with the exception of Trevor Burton and Chris ‘Ace’ Kefford, the band’s original bassist, they tended to steer clear of the Swinging 60s set. Ironically Kefford wasn’t too enamoured with Wood’s trippy tunes. “I always wanted the Move to be more Who-like,” he said “but Roy’s songs were more fairyland-like.” Or, as American producer Joe Boyd observed: “Beer drinkers’ psychedelia”.

While the Move soaked up the Carnaby Street couture, they still gave off the aura of the type of hippies who’d happily smash you over the head with a bar stool. Carl Wayne in particular was always telling people that “psychedelia is a con, it’s a fad. It’s a load of shit. We’re not psychedelic, we’re entertainers.” He took acid once, and had such a bad trip he was soon pining for his ale and cigs.

During the summer of ’66 the Move became front-page news when they embarked on an orgy of destruction at their gigs. During their Marquee season Secunda had no difficulty in persuading Wayne to wield a four-foot woodcutter’s axe on a bank of TV sets. Wood: “We didn’t have to do it but it was publicity, it put bums on seats. At the end of every set Carl would start smashing up the tellies and we’d all throw our instruments into the pile and rubbish ’em. It was very theatrical… On the last night of the Marquee season Bev Bevan threw his whole bloody drum kit on top of the guitars and smashed my Fender to smithereens. I was in tears when I came off.”

(Presumably Roy gave Bev a good hiding later? “No, I didn’t. He’s a big bloke, is Bev.”)

On their penultimate Marquee night that November, Wayne axed the stage itself, while club manager John Gee – weeping, by all accounts – begged him to stop. Instead, Wayne poured lighter fuel on the boards. As the flames licked, Gee ran on stage, whereupon Wayne ripped the distraught manager’s wig off and chucked it on the pyre. The audience rioted, the police were called, and Wardour Street was cordoned off; The Move, though, had made their getaway.

Similar riots ensued at the Speakeasy and at the Marquee’s annual Jazz and Blues Festival in Windsor on 30 July, the day England won the World Cup. “It came to a head on New Year’s Eve,” Wood recalls. “We played the Psychedelicamania show at the Roundhouse with The Who and Pink Floyd.” This legendary concert was billed as the event where ‘It’s all happening, man! Double Giant Freak-Out Ball. Come and watch the pretty lights.’

While the Move’s ahead-of-its-time light show and backcurtain films lulled the hippies, Carl Wayne upped his ante. “He didn’t just stop at TVs,” laughs Wood. “We had a 1956 Chevy on stage for him to break up. I was a bit embarrassed by it all, to be honest, but it had its moments.”

“Poor old Roy,” says Wayne. “He’s the most gentle of creatures, a really sweet fella, and for him to be stuck with the Move’s image was farcical. He didn’t approve of all that destruction, but I loved it and so did the audiences.”

Wood’s reasoning was more pragmatic: “Trouble was that it got us such a bad reputation it became an excuse for a lot of crooked promoters to withhold our fee. They’d say that people had been hurt by the flying glass, or that we’d gone and smashed up the dressing rooms. We never did that.”

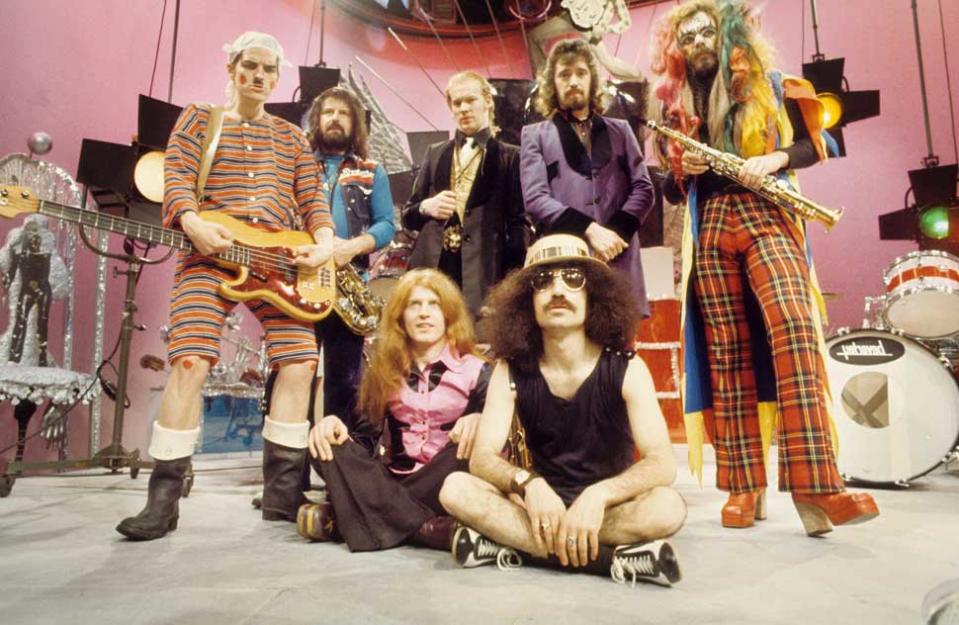

In 1967 the Move toured this mayhem in Europe, then returned for a college tour during which they took apart the London School of Economics. Then Secunda came up with another stunt: the infamous Harold Wilson Postcard case. In order to promote I Can Hear The Grass Grow, the Move’s third single and first for the Regal Zonophone label, the record was sent out to the press with a postcard containing a cartoon by artist Neil Smith which showed the then Labour PM frolicking naked in bed with his secretary Marcia Williams.

Now, The Move were already persona non grata with the establishment since Wayne chopped up a large effigy of Wilson during a benefit called Free The Pirates sponsored by Radio Caroline at the Alexandra Palace, a protest against the government’s silencing of the offshore pirate radio stations.

On the day of the single’s release, and completely unbeknownst to the Move themselves, Secunda posted off his 2,000 postcards, which had cost him £10, one of which fell on the mat of an aghast Colonel Wigg, Paymaster General and all-round security rottweiller for the Government.

The following week Wilson complained about the postcard (which was printed in the satirical magazine Private Eye) to the Conservative MP Quintin Hogg and instructed him in his role as Queen’s Counsel to give the scruffy oiks a damn good legal kicking. “It was a nightmare,” says Wood. “We were hauled into the Old Bailey and an injunction was passed. Three of us – me, Ace and Trevor – were still under 21 so we were classified as ‘infants’.” Secunda was summoned to Hogg’s chambers and given “a right fucking roasting”, but he was still unrepentant, since the band were on front pages of newspapers in Britain, Europe and America.”

The underground press sided with the band, and Private Eye turned them into a cause célèbre – after all, rumours of an affair between Wilson and his secretary were already rife in that publication. Tony Blackburn, fresh off the pirate radio ships, even played Flowers In The Rain as the very first single on Radio 1 to launch the BBC’s new, dedicated pop service. Predictably, the subsequently disgraced DJ Jonathan King slated the band in his column in Disc, which he regretted when Wayne cornered him on the set of Top Of The Pops and stuck one on him.

With Flowers In The Rain sailing up the UK chart, an agreement was reached out of court which forced the Move, and Wood in particular, since he’d written the song, to donate all their royalties to charities of Wilson’s choice, and to issue a grovelling apology.

Wood was, and remains, incensed. “To this day I don’t get a penny for that song – 43 years later! We’ve been getting the crap longer than the Great Train Robbers. I was, to say the least, pissed off at Secunda. I’m hoping for the day when I might as well be open about it again and get the publicity going. When I hang up me boots I want to leave something for me daughter Holly, because why shouldn’t she have it rather than that lot? When Carl was alive he tried to reopen the case. Rick Wakeman’s manager tried as well. They told him to get on his bike. Wilson’s representatives are still at it. You have to tread carefully or you could wake up with a crowd round yer.

“It was like a Mafia establishment thing,” he says. “We went to the Old Bailey but they didn’t allow us to take the stand.” The Court Usher described the group, who arrived in a red Rolls-Royce, as “wearing the gayest garb ever seen in this court, M’lud’. And then it got worse. “Apart from being hounded by the press, we suddenly noticed we were being followed by a big black car with the windows blacked out,” Wood says. “Two very heavy blokes from MI5 visited Secunda, scared the shit out of him. I wasn’t aware of phone bugging or physical threats myself, but they did enough. We’d be loading up our van after a gig and their car would be parked opposite. They made it quite plain they were watching us. That went on for several weeks.”

The effect was catastrophic. “There was a real danger that they’d try to make an example of us,” says Bev Bevan. The powers-that-be had their fingers burned by the Rolling Stones drug case and the ensuing public reaction. They’d closed down the pirates and suffered the backlash. Now they had the chance to finally win one…” Even Wayne admitted that they “were very scared. We just did what we were told. This was the Prime Minister we were dealing with, and we were very naughty boys.”

With Flowers In The Rain peaking at No.2, in April ’67, the Move embarked on the most prestigious package tour of the year, joining the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Pink Floyd, the Nice, Eire Apparent, Outer Limits and Amen Corner, travelling on a fleet of buses. “I used to get stoned just walking to me seat,” laughs Bevan. For Ace Kefford and Trevor Burton this was as good as it could possibly get. Burton: “There was a lot of shit going down on the bus. All the girls and dozens of musicians – you can imagine. I got on great with Jimi and the Experience, to the extent that I shared a house with Noel Redding in Wandsworth for 18 months. With that, and hanging out with Traffic, I knew I didn’t want to be a pop star much longer.”

During the tour, Kefford and Burton got themselves fixed up with permanent wave Afros. “Ace’s wife was a hairdresser,” Burton recalls. “It was just a mad moment. I kept it for a year and then me hair started falling out in large chunks.” The two babies in the band also got heavily into liquid LSD.

“It was still legal then,” Burton says. “We’d get it in a dropper bottle and put it on sugar lumps. You never knew what the dosage was. It didn’t do Ace any good though. He was crazy anyway, and that triggered his [then undiagnosed] bipolarism and he went off the rails. Only Ace and me took drugs in the Move; we were like kids a sweet shop. Our other thing was amphetamine. When you’re gigging six nights a week you don’t mind a little help…”

That package tour was Secunda’s last significant involvement with the Move. Rather than follow up Flowers… with the mooted choice of Cherry Blossom Clinic (a song about a psychiatric hospital), the band returned in the New Year with their most abandoned singled yet, the magnificent Fire Brigade – ditching flower power for black leather and motorcycles – and finally released their debut album, Move, with psychedelic cover designed by Dutch artists The Fool, who basically rejigged artwork The Beatles had rejected for Sgt. Pepper. “The album was a disappointment,” says drummer Bev Bevan. “Too many singles and B-sides, so it didn’t sell well. We did all the underground scene clubs with Cream, Small Faces, Joe Cocker, Floyd and The Who but it didn’t do us much good. We should have buggered off to America with Hendrix, which we could have done, but Secunda never saw the bigger picture.”

The derailed Kefford quit after the album’s release, and while the Move were recording their Live At The Marquee Club EP. The group had also tired of Secunda’s stunts and sacked him in Spring 1968. “We just tore up his contract because we were scared” said Wayne. Enter impressario Don Arden, an agent with a fearsome reputation. Arden’s presence in the wings may have hastened Kefford’s departure “but all that home-made LSD had really screwed him up. Trevor stayed in great nick somehow. Considering what he got up to with Traffic and Paul Kossoff, he should have been dead.”

Having nothing else on the chart in 1968, The Move began to look like an anachronism. Bevan: “Our loyalty to the English audience cost us. And Woody was finding it harder to write hit songs to order. There was a lot of pressure on him. When we did come back in 1970 with the Shazam album, a great heavy record, it was too late. The original band was way past its best.”

The Move MkII, with Burton on bass, did have a No.1 hit – the dark Blackberry Way, produced by Jimmy Miller. Wood and his old mate Jeff Lynne demo’d the song over Christmas at Lynne’s parents’ house. “I love it now, but I didn’t appreciate it then so I quit,” says Burton. “It was more like the Roy Wood Band than the Move, and I’d had enough of them. We had different lifestyles. I was living in London or Berkshire and they were driving home to Birmingham after every gig.

“A big problem was also the absence of money. Apart from live money I never saw anything apart from one solitary cheque for £1,000. That’s all I ever got – until this day. Everyone ripped us off, Secunda and his partner Denny Cordell particularly. Cordell was a great guy and an absolute arsehole. He’d be your mate, then tell you that friendship and business didn’t mix, which was great news for him.”

Burton’s decision to leave didn’t come as a surprise to the others. “They just said good luck.” In came 24-year-old Rick Price from Birmingham band Sight & Sound. “Roy collared me in a car park and said he had a proposition,” Price recalls. “I thought it was a drug deal. I knew the Move because I was a huge fan, but the rumour was they’d offered the job to Hank Marvin from the Shadows and that Jeff Lynne had turned it down.

“Don Arden sold his management stake to Peter Walsh, who managed bands like Marmalade and the Tremeloes, and he put us on a shed tour in Ireland and at cabaret clubs like Batley Variety. Carl didn’t mind that because he said: ‘It’s good money.’ He didn’t want to be in an underground band any more. Roy hated it, though, so we’d always play the hipper places as well. It was a very weird existence. There was certainly no sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. It was all tea and biscuits after the gig.”

In October ’69 the Move made it to America, but to say they toured would be stretching it. They played just three cities: LA at the Whiskey, San Francisco’s Fillmore West, and the Grande Ballroom in Detroit opening for the Stooges. According to Price, “we should have gone to America when Blackberry Way was out, but that tour was delayed.”

In true Spinal Tap style the band invited themselves to the offices of their US label, A&M. “We sat in this bloke’s office twiddling our thumbs,” says Price, “and he didn’t have a clue who we were. Eventually he pulled out a bunch of singles, dusted them off, and right at the bottom of the pile was ours. He just said: ‘Oh, that’s who you are.’ They really were taking the piss.”

A dispirited Move returned to the UK cabaret circuit just as the first wave of British heavy metal came thundering out of Birmingham and the Black Country – a movement the Move had instigated but would never get the credit for – followed closely by glam rock, whose outrageous costumes and theatrical make-up were as much Roy Wood’s invention as they were David Bowie’s.

Like Shazam, the band’s final albums, Looking On and the epic Message From The Country, failed to chart, but with Jeff Lynne’s arrival, Wayne’s departure and Price’s discovery that he’d been dropped without apology, the Move story was about to take ever more peculiar detours – via Electric Light Orchestras and Wizzards. Those are stories for another day.

In 2010, at home in his converted Derbyshire countryside pub, the great Roy Wood was as diffident as ever. His opening remark had been: “I’m a bit brain damaged but I’ll be alright one day,” but his Music Book project – “stuff I’m not embarrassed to play to me mates” – reaffirmed his talent. “Would I re-form the old band? I don’t want to be a nostalgia act on a package tour. My only regret is that I didn’t have the technology to make our records sound better. I’m obsessed with sound. Most people don’t know who I am any more. Even round here I’ll go out and play a gig and I’m the bloke who did that Christmas single who wears the red glasses; they don’t know about the Move. I’m just one of the locals…

“I’m certainly not a recluse, I just don’t want to be a rock star. I want to be seen as a decent man and musician and a songwriter. I wouldn’t mind a hit single again. Not to get on Top Of The Pops, but just so my rock’n’roll band could get more work. I should put out more music online… but I dunno about the old stuff. You lose the desire. I wouldn’t say I wasn’t interested in doing it again… I am in a way. But it’s hard, mate.”

The original version of this feature appeared in Classic Rock 152, published in December 2010. Rick Price died in 2022.