“Prog fans were saying that simple songs are bad songs and that really annoyed me!" Pain Of Salvation on why songs were the focal point of the Road Salt albums

Swedish prog metallers Pain Of Salvation completed their Road Salt project with the release of Road Salt Two in 2011. Prog sat down with mainman Daniel Gildenl?w to fnd out why it was so important he wants let the song be the focal point.

As the progressive rock realm expands in all directions, it becomes increasingly easy to spot the difference between those bands who genuinely embrace notions of experimentation and musical bravery and those who simply regard “prog” as some preordained and unmovable musical style to be co-opted and reproduced ad nauseam.

Not that there’s anything wrong with bands who just want to sound like Pink Floyd, King Crimson or Genesis, of course, but it’s hard not to feel a slight twinge of regret that so few bands want to be as brave or as remorselessly contrary as Sweden’s Pain Of Salvation. Over the course of eight studio albums – the latest two being last year’s magnificent Road Salt One and the brand new Road Salt Two – founder and leader Daniel Gildenl?w has taken his band on an extraordinary journey, and one that truly encapsulates the essence of what, in a perfect world, progressive rock should really be about.

Although once regarded as definitive purveyors of that tricky beast prog metal, Pain Of Salvation have evolved to the point where fans now expect each new record to be an exercise in confounded expectations and blindfolded detours. From the lavish psych-metal explorations of Remedy Lane to the overwrought intricacy of Be and on to the barking mad genres-in-a-blender antagonism of 2007’s highly divisive Scarsick, Gildenl?w has proved himself to be both an inveterate risk-taker and one of modern prog’s most laudable artists. On his two latest works, he has also proved himself to be a master of earthy, Beatles-tinged proto-metal that comes drenched in the warm tones of the analogue age and shrouded in symbolic pot fumes. The Swedes’ latest aesthetic side-step seems to be the latest in a series of disorientating curveballs, but the man behind it all is reluctant to concede to accusations of musical schizophrenia.

“Between Scarsick and Road Salt One, the step is not necessarily as large as you may feel on the receiving end!” Gildenl?w laughs. “The overall sound makes a big difference, of course, but one thing that people tend to not realise is that when we released our first album Entropia back in 1997, it wasn’t the true beginning of the band, even though that became the music and sound that everything since has been compared to. But at that point we’d been playing as Pain Of Salvation since 1991, so that’s six years, and before that we’d played under a few other names, and I formed the band when I was 11 in 1984 and I never quit that band! So when you hear the 1997 Pain Of Salvation, it is a band in the middle of a long journey and there were lots of transitions and changes before that and it just kept going. To me, it’s very important that you keep redefining music for yourself and that you keep travelling. The bands that I have personally enjoyed the most, they display this same state of constant change. You have The Beatles and Queen and Abba and Faith No More… a lot of these bands kept developing and they didn’t become a repetition of just one idea. Those bands made music for themselves and that’s very important to me, when you make any sort of art.”

Even taking that desire to constantly reassess and redefine his music into account, the contrast between Scarsick and the most recent Pain Of Salvation material is pretty remarkable, not least because the earlier album seemed to take the Swedes into territory – thudding rap-metal, of all things! – that was always going to confound and enrage a sizeable portion of their fanbase. Similarly, the Road Salt albums have faced a mixture of confusion, elation and outright hostility from an audience that probably should have learned to expect the unexpected by now.

“If people want one thing, we’re sure to give them the other thing instead, because that’s how we work!” states Gildenl?w. “We always have a slightly rebellious approach to things, I think. On Scarsick, the first three songs have all these rap elements and they’re very different songs from what people were used to from Pain Of Salvation. Overall the album is not that different, but I’ve always said you judge an album by the first three songs and the last song. Those four songs make a huge impact on how the album is perceived. So we very intentionally chose to start off rather harshly, not making it easy for our fans. That’s what we did with Road Salt One, too. The first three songs are really Beatles influenced, and that’s a huge change from the first three on Scarsick, but the second half is not that far from the second half of Scarsick!”

In a sense, both Road Salt One and Two are records that offer a less daunting challenge to the average fan of progressive rock, both ancient and modern, not least because of the way the band have settled so casually and naturally into the role of a nominally old-fashioned hard rock band. It also helps that Gildenl?w is a phenomenal songwriter who truly inhabits the forms he adopts, resulting in a disarming authenticity that swiftly allays any fears that this latest incarnation of the band represents some self-consciously retro conceit. What the albums will not do is placate those who felt betrayed when they shrugged off their prog metal affiliation and embraced a more straightforward compositional outlook.

“I used to go on all the progressive forums online and I remember at the Perpetual Motion conference, they had this discussion about songs with not many chords in them,” he recalls. “People were effectively saying that simple songs are bad songs and that you can’t make a good song that’s simple. And that really annoyed me! These people were claiming that they were superior and had wide and broad minds, in contrast to the narrow-minded mainstream music fans, and yet I could see the exact same symptoms of narrow-mindedness. So I decided to write a song with just three chords and the exact same progression throughout the song.

"I wrote Ashes, which was on The Perfect Element, and it’s built on three of the most common chords that you can think of, just going over and over again. Of course, it was voted the best song of the year at the Perpetual Motion conference the following year! That was a huge victory. I guess no one at the conference ever realised, but for me it was a way of proving something to myself. Every musical style has its own uniforms and norms, prog metal included, and as long as you stick rigidly to those norms, you’re no better than anyone else. It was the exact same narrow-mindedness, just in a different colour."

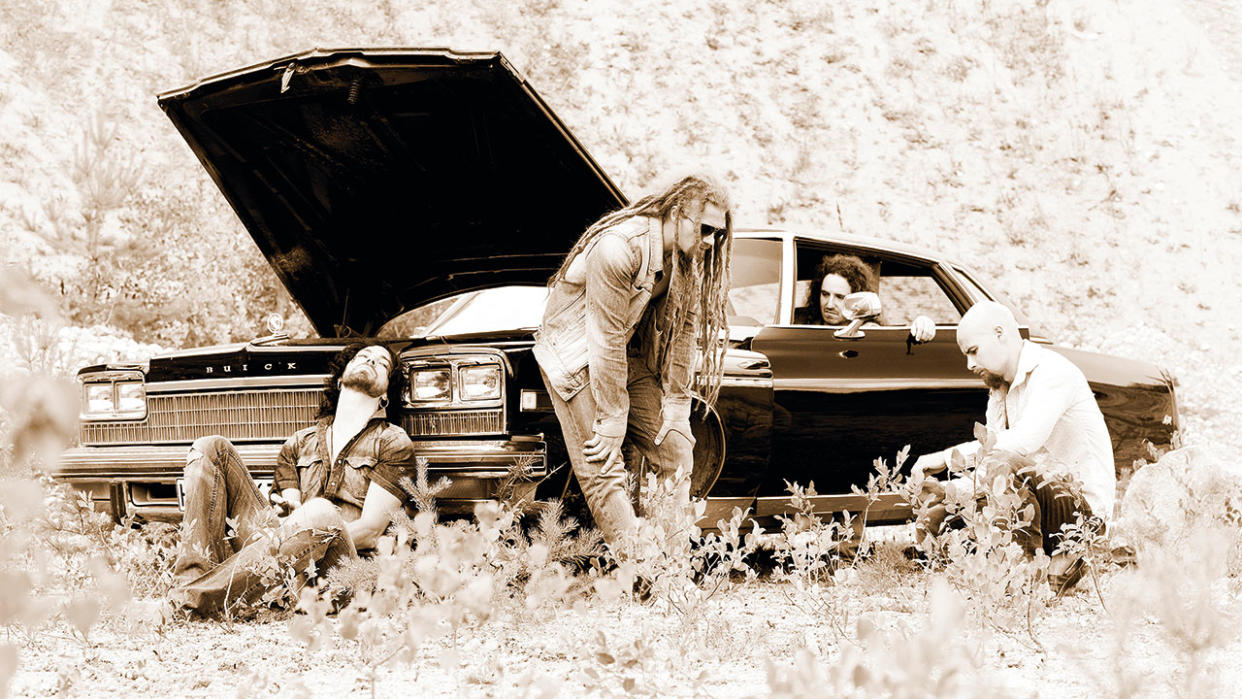

Beautiful albums that hark back to a time when the pursuit of warm, natural tones and unsullied ambience were the mark of a top quality recording, Road Salt One and Two do not represent a wholesale rejection of Pain Of Salvation’s previous efforts by any means, but the enthusiastic saluting of a revered bygone era suggests that Gildenl?w is attempting to recapture an atmosphere and a spirit that were once ubiquitous but that have long been processed, compressed and airbrushed from the majority of rock music, progressive or otherwise.

“What happened was that increasingly I’ve become sick and tired of the modern sound, because I’ve just realised that modern music doesn’t speak to me anymore,” states Gildenl?w. “Nothing moves me, nothing really talks to me, and so I thought: ‘Okay, maybe I’ve developed or matured or something!’ But then when I went back to music that I grew up with, I really felt something again. So I started listening to music that I’d never heard in my whole life and I realised that music from the 70s just reaches me in a completely different way. In the 50s and 60s they were still struggling a lot with getting a great sound and it’s sometimes hard to hear what they play because the sound is so bad, and in the 80s and 90s, it’s hard to hear what musicians are playing because the sound is so good! The 80s and 90s are lost causes to me, from a sound point of view. I find it difficult to listen to any music from that time. Road Salt One and Two are the symptoms of an allergy that I’ve picked up, an allergy to synthetic reverbs, fake room sounds and getting everything to sound impressive while sacrificing musical clarity and that raw, aggressive vibe that just reaches into your guts and twists them. No music from the 80s can do that to me. No slick, nice reverb can twist my guts! This is a stand against the modern sounds that have just become stupid and pointless.”

Originally intended to be three separate albums, Road Salt One and Two eventually mutated into their current form; two closely-related but still contrasting albums that relay a series of tales depicting an assortment of characters who find themselves confronted with “a possibility and a sacrifice”. Like all of Gildenl?w’s concepts, it is a shrewd blend of the intensely personal and poignant and the willfully overblown; a formula that has served the band well over the years.

Given the intensity and multi-layered nature of everything that he does under the POS banner, it seems extraordinary that Gildenl?w is still able to pursue his extra-curricular activities with the likes of Transatlantic, The Flower Kings and Mike Portnoy’s Led Zeppelin tribute Hammer Of The Gods. But then Daniel Gildenl?w is one of those people, common to the prog realm, who seem to leak music from every pore and portal.

“With Pain Of Salvation, every time I go on stage I know that I’m going to run a marathon and I’m gonna be mentally and physically drained afterwards because it takes so much from me,” he notes. “When I go on stage with Transatlantic or

The Flower Kings, it’s a fun day at work, you know? I can relax to a much greater extent. I’m not there as the main focus of the band. I’m a guy who glues stuff together, pretty much, and that makes it interesting. In Pain Of Salvation I’m the one calling the shots at all times and it’s pretty nice to be at the other end of the table every once in a while. It’s a vacation in the most positive of ways, and at the end of every tour that I’ve done with another band, I’ve always been longing to get my teeth back into Pain Of Salvation again.”