Promise That You Will Sing About Me: The Artist’s Burden in Desperate Times

Art by Suede Jury

By Jon Tanners

An artist’s duty, as far as I’m concerned, is to reflect the times. I think that is true of our painters, sculptors, poets, musicians…as far as I’m concerned it’s their choice. But I choose to reflect the times and the situations in which I find myself. That to me is my duty, and at this crucial time in our lives when everything is so desperate, when every day is a matter of survival, I don’t think you can help but be involved.

Dope on the corner, look at the coroner

Daughter is dead, mother is mournin’ her

Strayed bullets, AK bullets

Resuscitation was waiting patiently but they couldn’t

Bring her back, who got the footage?

Channel 9, cameras is looking

It’s hard to channel your energy when you know you’re crooked

Banana clip, split his banana pudding

I’m like Tre, that’s Cuba Gooding

I know I’m good at

Dying of thirst, dying of thirst, dying of thirst

— Kendrick Lamar, “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst”

On the morning of Friday, July 8, I cried listening to ScHoolboy Q’s “Ride Out.” Midway through a long drive, the menacing bass consumed me like a wave.

It was the culmination of a wretched week—a week of violence that unnerved, numbed, angered, and confused in alternating measures, a week that once again saw cops killing black men and, in a new turn, saw the retaliatory killing of cops.

The song swarmed my car, its ominous sonic weight a more effective commentary on the week than a song specifically addressing events of the preceding days. With music’s intangible coloring, it captures a testimony of distressed experience, the paranoia of a life lived ever on the edge transmuted into crushing music. Q snarls: “Bruh, this ain’t the eighties, mane/Niggas shootin’ everything, everything.”

Though Q is rapping specifically about the modern climate of gang conflict, this promise of wanton, senseless violence hangs over Q’s stunning new album Blank Face LP like the pall that currently cloaks America—the bitter assurance that each week will bring a new procession of slain names.

It is easy to recoil in horror at fresh bloodshed. The week of July 4 delivered plenty. Policemen erased the lives of Alton Sterling and Philando Castile in Baton Rouge, Louisiana and St. Paul, Minnesota, their names made hollow memorials as hashtags. Sterling and Castile’s deaths spurred the killings of officers Lorne Ahrens, Michael Smith, Michael Krol, Patrick Zamarripa, and Brent Thompson during a peaceful Black Lives Matter protest in Dallas, Texas, and the subsequent killings of officers Montrell Jackson, Matthew Gerald, and Brad Garafola in Baton Rouge. The death toll promises to rise as long as black men and women continue to die on the other end of officers’ guns—continue to die unjustly, period.

July 2016 should be remembered as one America’s darker months, but this violence is not new. The litany of the slain is not new. The death of Michael Brown in 2014 may be seen as the inciting incident for two years of heightened tension between black Americans and police officers. Even that moment was but a new public face on issues of systemic racism and violence with roots hundreds of years deep.

An artist’s voice is a great gift and a necessary one in a time, as Nina Simone so painfully put it, when ‘every day is a matter of survival.’

As the world burns for every cellphone camera to see, avoiding involvement in dialogue is a perilous choice. We need our artists to testify—it is a burden that accompanies the privilege of having a platform. An artist’s voice is a great gift and a necessary one in a time, as Nina Simone so painfully put it, when “every day is a matter of survival.”

The morning after the Dallas shootings, I saw my friend Michael Uzowuru—a Los Angeles-based producer/artist who’s worked with Earl Sweatshirt, Vince Staples, Frank Ocean, Anderson Paak, Vic Mensa—writing poignantly about the week of violence on Facebook, a place not typically known for nuanced, vital thought, though now a common ground for verbal prostration in the face of grief and absurdity.

“My first thought is ‘again’ and sadly I’m not surprised,” he said in a subsequent email correspondence. “I’m numb, but in agony, and that’s the deepest form of pain I’ve ever felt. it’s crippling to say the least, so at times it’s beyond difficult to even muster the courage to speak up.”

“This is what makes it so difficult for me to decide what the artist’s duty is in this time, especially for black artists or any artist who identifies with whoever’s being oppressed or harmed,” he continued. “It really differs from artist to artist and I think the best thing any artist can do, first and foremost, is take care of themselves, because their existence is a statement in and of itself.”

How can one be carefree in a country that so consistently disdains black life—disdains the life of any of its citizens?

Q’s fourth album plays as modern deliverance on Simone’s edict, echoing Uzowuru’s understanding that being alive can be politically meaningful. Blank Face LP is autobiography as protest, documentation implying a call to action, an often angry, violent window into a world many have never seen (and some actively choose not to see). Even in celebration, an air of mourning and fatalism hangs around it.

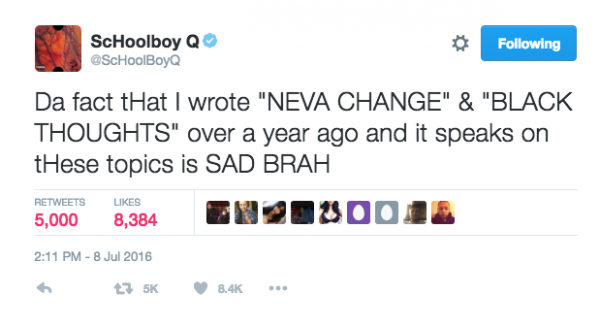

Blank Face LP feels both prescient and reactive. It is haunting that it arrived at the close of one of America’s darker recent weeks, a seeming gift of horrific second sight. And yet it is the sure product of a painful past, as Q himself noted on Twitter.

A common thread in the weeks since the storm: This violence is not new. The cameras are new. The infinite news loop is new. The need to film each interaction with police as a matter of evidence and survival is new. The atrocities on autoplay are new. The violence has existed; the scars date back hundreds of years.

Q’s latest work updates classic gangsta rap sounds and symbols with a certain dystopian darkness, observing dangerous life through the pitch black tint of a world filming its own attempted suicide.

Albums like Blank Face LP can be a tool for igniting discourse and increasing awareness—an apparatus aiding the survival Simone discussed.

“A lot of people may not see [the world] from your perspective, so when you tell it, it gives that listener a chance to see it in that way,” says Desi Mo, a Long Beach rapper and Vince Staples collaborator, via phone. “If you’re not out protesting, the way that you’re presenting this information to somebody who’s listening can make them go out and do it, can make them reconsider the way they’re living their own life.”

It seems as though no tragedy is enough to get us to wake up and change, so how can a song move men and women where atrocities have not?

Yet in a time when each night wracks sleep with fear of the next day’s news, it makes the urge to bear witness and create art feel futile, a whimper into the void. It seems as though no tragedy is enough to get us to wake up and change, so how can a song move men and women where atrocities have not? L.A.’s Boogie spoke to this paradox of the urge to speak in the grip of helplessness on “Hypocrite.”

I don’t even wanna get asked ‘bout it

It’s hard enough for me to rap ‘bout it

Without me thinking I’m a hypocrite

I should be out here in the shit, not trying to make a track ‘bout it

Boogie’s confusion is as important as any clear prescription. It is an honest response to an era dredging up the same despicable questions and leaving few easy answers, aside from the should-be truisms that innocent black people must stop being killed by police officers and that increased violence will not end our problems lest that end be in complete annihilation.

Boogie’s response is also indicative of the sort of music we need right now: honest and brave, specific and personal, potent without being pedantic or condescending. It bears the same power as Q’s street journalism and grim humor, the ability to provide a window into a world and ignite discussion for those on the periphery.

On the Black Hippy remix of his rising single “THat Part,” Q shows one logical end of Boogie’s confusion, an eruption of fatalistic rage:

Gangbangin’ like we stand for somethin’

When Alton Sterling gettin’ killed for nothin’

Two cowards in the car, they’re just there to film

Sayin’ #BlackLivesMatter should’ve died with him

Wrong nigga in your hood, you gon’ ride on him

White nigga with a badge, you gon’ let that slide?

Tell me how they sent that footage off and slept that night

I feel bad that my daughter gotta live this life

I’ll die for my daughter, gotta fight this fight

Q’s new verse gives voice to bewilderment and anger, justifiably boiling over in the face of unending injustice. The call for retaliatory violence is a dangerous one, but understandable when video records of innocent people being killed seem powerless to prevent future killings.

In the face of mounting horrors, testimony is important, especially when it arrives in increasing concentration and encourages others to testify–to tell their stories and share perspectives that might otherwise get pushed by the wayside. Rage, ignorance, and cynicism are not acceptable excuses for silence.

While we may not have reached a critical mass yet, the last few years have seen a promising swell in impactful biographic and observational music: YG’s My Krazy Life and Still Brazy, Vince Staples’ Summertime ’06, Anderson Paak’s Malibu, Boogie’s The Reach, Kamaiyah’s A Good Night In The Ghetto, Kodak Black’s Lil Big Pac, Earl Sweatshirt’s I Don’t Like Shit, I Don’t Go Outside, Run The Jewels’ self-titled second album, among others. Outside the strict boundaries of hip-hop, Beyonce, D’Angelo, Dev Hynes, Solange, Anohni, Shamir, Tunde Olaniran, and Kevin Abstract have all made moving musical statements by mining experience—their own and that of others.

Music finds political power in this exploration of human truths—through plumbing the depths of specific emotion to identify commonly shared feelings and create a language for navigating this world.

If artists happen to be cogent political and social thinkers beyond their music like Killer Mike, Frank Ocean, or Tom Morello, all the better, but they need not be the ones changing policy. To paraphrase Tupac, our artists don’t have to change the world, but we need them to inspire those who will.

“Our perks, our outlet, and our platform all accounts for our privilege, and I think that allows us as artists to still be very effective when it comes to shaping cultural movements and commenting on current events,” says Uzowuru. “Comments on current events can be used as discourse and I truly believe discourse leads to the cultural movements that are so needed.”

For many, the desire to be outspoken can be crippled by the inertia of despair, the sense that one action—a song, a tweet, a conversation—will have no impact. Small contributions eventually form larger movements and have the power to push thought forward, even if only on a grassroots level.

“I think even upcoming artists, their music is so influential,” says Desi Mo. “Even if you say something small—you don’t have to make a whole record about the situation—but I think an artist showing that they care, even a little bit about the situation, I think it has the power to make other people care about it.”

Testifying is an act easier said than done, but now is a time for courageousness, even in the face of mounting obstacles.

If ever there is a time for our artists to be present, it is now. Be present in clarity or confusion, in anger, in mourning, in celebration of what beauty life does hold or in despair that human beings continue to treat each other so terribly. Testifying is an act easier said than done, but now is a time for courageousness, even in the face of mounting obstacles. To be absent is to be silent as a battle rages between progressivism and regression, humaneness and hate, people pleading for peace and violent nihilists—life versus untimely death. We see this vile, brutish possibility rearing its head: In Trump’s virulent, bigoted speeches and the ugliness they inspire, echoing America’s dark past and the climate of vulnerable Weimar Germany. In the increasing division of our major political parties. In the unceasing escalation of violence—in the United States, in France, and in countries like Bangladesh that continually receive short shrift in the rotation of tragedy paraded around by major news outlets.

“There is no one way to be political,” says Zuri Marley, Blood Orange collaborator and granddaughter of Bob Marley. “You can care. You can give a shit. Show up. That’s my current mantra. Show up for yourself, which in turn allows you to show up for other people.”

More from Pigeons & Planes