Q&A: Adia Victoria on PBS' 'Southern Storytellers' series, the blues, Nashville's growth

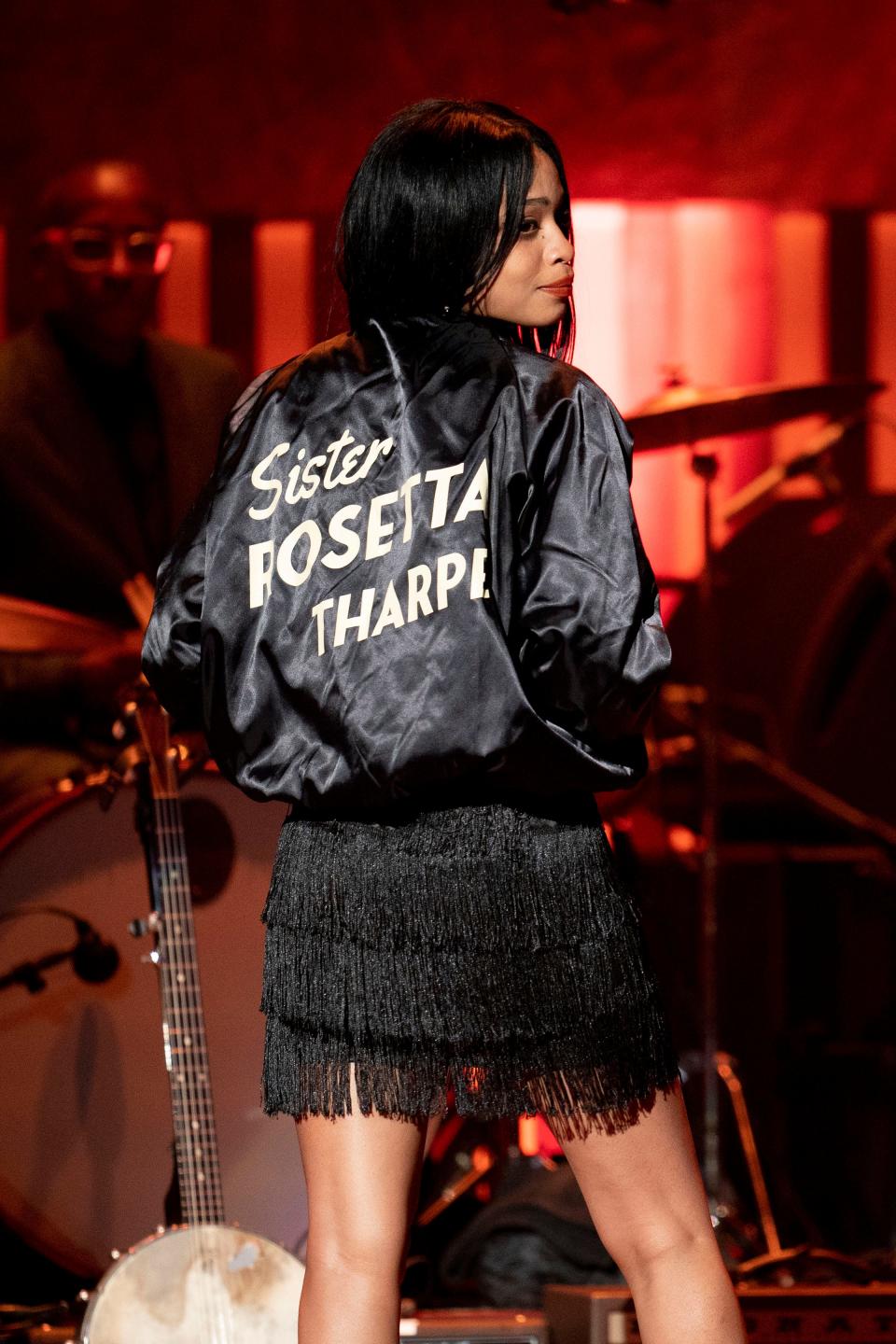

Nashville-based musician Adia Victoria's birthright and acclaim as an African-American and South Carolina-born performer of the blues makes her potentially the most ideal contributor to PBS and Peabody Award-winning filmmaker Craig Renaud's partnership for the new three-part documentary series "Southern Storytellers."

The series airs weekly, July 18-August 1, on PBS, from 9-10 p.m. ET / 8-9 p.m. CT.

Victoria notes that every aspect of her life and art -- from the music she's made for the past decade to her brother's recipe for ribs -- have been directly influenced by her Southern upbringing. Via the documentary, her October 2022 wedding to fellow musician Mason Hickman -- another moment intrinsic to how she views her connection to the American South -- is captured.

"The people highlighted in ["Southern Storytellers"] deserve to tell stories that don't look and sound like stories typically celebrated and centered as a part of the Southern narrative," Victoria said.

The miniseries covers stories from a 3,000-mile oval stretching as far north and east as Vietnamese-American performer Thao Nguyen's roots in Falls Church, Virginia, south to Tarriona "Tank" Ball's (of Tank and The Bangas) New Orleans home and as far west as Lyle Lovett's Houston.

"'Southern Storytellers' comes from our desire, as native Southerners, to show the South in an authentic light," said Courtney Pledger, executive director and CEO of Arkansas PBS.

Also included in the series are music artists Jason Isbell and Amanda Shires, songwriter/actors Mary Steenburgen and Billy Bob Thornton, and poets Jericho Brown and Natasha Trethewey. Their ability to "reveal a vivid patchwork of diverse American stories that celebrate the resilience and joy of Southern people" are worth highlighting, Pledger said.

A recent conversation with the ever-frank Victoria, was revelatory in regards to the strength of empowered and fearless Black voices in this -- or any -- era.

Question: Americana as a sub-genre can be said to be experiencing its 25th anniversary soon, and country music is a century-old and more popular than ever. How do these notions impact the value of recontextualizing the value of the South and its stories in modern conversations? Is the South fundamentally a different place now compared to 25 and 100 years ago? Why does that matter?

Adia Victoria: The South is a more revealed place than it's ever been. Because we're all looking at power dynamics and systems with a more critical eye, the ability to blanket over the region's more complex, complicated, troubling and unsavory aspects with baseball, beer, guns, Jesus and religion isn't cutting it anymore. People are no longer willing to accept anything at surface value. "Southern Storytellers" is important because [now, more than ever] we must identify what and who contributes to modern Southern culture -- "giving it its flavor and groove," so to speak.

Question: While watching your segment in the documentary, you joke about how your book collection has grown so voluminous that you don't have enough shelving to contain it all. Being that you're so well-read -- and one listen to your musical catalog shows that influence -- what is the value of Southern folklore to your artistry?

Victoria: Folklore endures. That's its greatest power. It's relevant to whatever place, situation, or time it's rediscovered because, since human beings have a very limited skill set of how we react to circumstances, we don't change. Using folklore to cut myself down to size and scale to remain centered when I feel like I'm experiencing something "unprecedented" or I feel alienated from my surroundings, those words snatch me back into realizing that I'm just the latest in a lineage of people who continue to experience the human condition.

Question: One of the most powerful scenes in all of "Southern Storytellers" is the planting of a magnolia tree in your front yard at your wedding. Why did you choose to include this moment?

Victoria: For Mason and I, having us and our guests plant a magnolia tree at our wedding ceremony was symbolic of our love as not just a nuclear thing we keep behind our home's walls. Instead, it's a communal thing made possible by everyone in attendance -- they water us, sustain us and keep us rooted and grounded in our humanity.

I also have a well-documented adoration of magnolia trees -- they're emblematic of spending my childhood in South Carolina climbing them and imagining my future under them -- but it's also free landscaping, too (laughs).

Question: We'd be remiss if we didn't discuss the blues in this conversation. There's a resurgence of a particular rock n' roll variant that plays well with the blues and its traditions. As a Black person who claims heritage in that tradition, what are your thoughts about the blues and its relevance and employment in this musical era?

Victoria: My life -- and the way that I move through it -- is a blues song. The genre, its traditions and my ability to continue using the blues to acclaim my subjectivity are the most valuable heirlooms passed down to me as a Southern Black woman. The appropriations of the blues that have and continue to happen over the past 50 years symbolize colonizers getting too comfortable and familiar with [the blues]. Replication of Jimi Hendrix and Robert Johnson's guitar licks and solos does make you proficient and copying styles -- it does not equate with being a "blues person."

The blues occupies a sacred, cultural place in my body that comes from other Southern Black folk's blood, sweat and tears, refining a sound and style for centuries. White people are audacious to believe there should be any ease in claiming [the blues]. They claim it because they have -- in many ways -- removed Black autonomy from artistic genius.

Stating that Robert Johnson learned the blues from the devil at the crossroads thieves him of the same autonomy that we give, say, Beethoven when discussing how he learned to master his craft through dedicated labor.

Question: You also take the time to prepare a meal while being filmed by the "Southern Storytellers" documentary crew. It feels like the most authentic look into your most honest self. Why was this included?

Victoria: Instead of having pictures of how I grew up, I have my family's recipes that are familiar to my childhood -- and they aren't written down. For many Black people, cooking requires a [intuitive] knowledge and sense of food preparation entirely based on the joy we're emotively trying to drat from an ingredient. The element of self-trust required in that type of work [is derived from] the idea of scarcity and necessity being the mother of invention in Black life ever since we were slaves given leftovers and scraps to turn into well-prepared food that sustained our bodies and souls.

My grandmother's corn, okra and tomatoes, Aunt Pinky's macaroni and cheese and my brother's ribs are the family snapshots that resonate most with me that I treasure. Instead of looking at photos posed in studios [observing] the way Black Southern folk eat and pass recipes between generations is the best way to think about how Black Southerners are together in communion with our elders and current and future generations.

Question: You have lived in and currently live near the city of Nashville proper. What are your thoughts about Nashville as the quintessential modern -- both Southern and American -- city in 2023? How does this documentary series reflect how people can and should think about cities like Nashville moving forward?

Victoria: Nashville is an interesting case study of the ways of capitalism and colonization. By necessity, since Christopher Columbus got lost on his boat and ended up in America instead of India, capitalists and colonizers have needed to consume, conquer, devour and extract from that which they admire and value. Systems that require infinite growth often become cancerous, grotesque and warped versions of themselves.

I'm worried that Nashville's lost so much of the texture of its traditions that it has become its most efficient, expanding, expedient, homogenized and wealthy version of itself. The city's working class could become so marginalized [compared to its non-working-class growth sectors] that they will not share the growth the city is experiencing.

Therefore, documentaries like "Southern Storytellers" allow for burying our treasured [classic] traditions in the ground so that decades or centuries after [this era], someone can find it and know that what the surface of [a city like Nashville] represents is only just that -- and that beneath it all, the actual treasures of dynamic, precious, recoverable and unresolved stories exist like gems hidden in the ground.

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Q&A: Adia Victoria on PBS' 'Southern Storytellers' series, the blues, Nashville's growth