R. Kelly's year of reckoning: 'He's never going to breathe fresh air again'

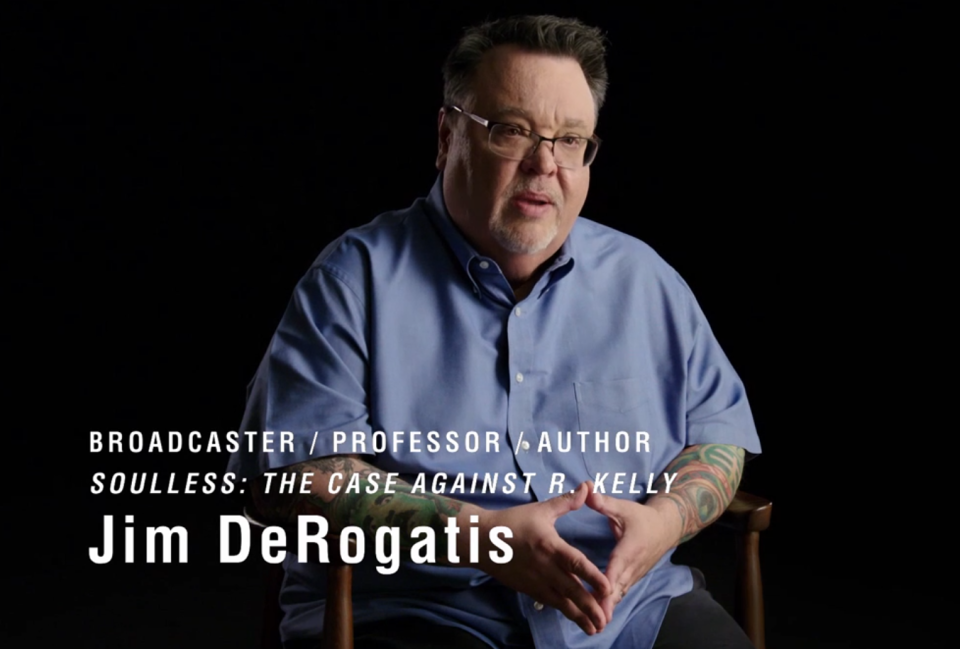

In the first week of 2019, the music world was rocked by Surviving R. Kelly, Dream Hampton’s six-episode Lifetime documentary detailing horrific sexual abuse accusations against disgraced R&B superstar R. Kelly. (Kelly has denied all allegations.) Two weeks after the docuseries aired, amid public outcry, Sony Music dropped Kelly from its roster without comment. A few months later came the publication of the book Soulless: The Case Against R. Kelly by Jim DeRogatis, a veteran music journalist-turned-investigative reporter who’d been chronicling the Kelly saga for nearly two decades. And by the end of 2019, Kelly was behind bars, awaiting trial on multiple charges and potentially facing more than 100 years in prison.

DeRogatis’s involvement in the Kelly case dates back to the start of the millennium, when as a Chicago Sun-Times pop critic he received an anonymous fax the night before Thanksgiving 2000, alerting him about an ongoing investigation of Kelly by the Chicago Police Department’s sex-crimes unit. DeRogatis and fellow Sun-Times reporter Abdon Pallasch began investigating the story, and a year later, they received another, much more shocking anonymous dispatch: a videotape featuring Kelly engaging in a sexual act with an allegedly underage girl. Then in 2002, when Kelly was arrested and indicted on 21 counts of manufacturing child pornography, DeRogatis was there to cover the case — and was even ordered to testify about the sex tape in the trial.

When Kelly was acquitted of all 21 of those charges in 2008, many industry insiders and fans alike seemed willing to forgive, forget, and quickly move on. But DeRogatis continued with what by now had become a personal crusade. In 2013 — the year that the author calls “the year of indie outreach,” when Kelly released the sexually explicit Black Panties album, played the Pitchfork and Coachella festivals, and even joined Lady Gaga for risqué “Do What You Want” duets on Saturday Night Live and the American Music Awards — DeRogatis spoke with the Village Voice about what he had witnessed while covering Kelly’s “stomach-churning” child pornography trial. That article went viral, but Kelly’s professional success continued into 2014 and beyond. In 2017, DeRogatis’s explosive exposé for BuzzFeed about what he described as Kelly’s “sex cult” also made waves, but again, the resultant outrage quickly fizzled out.

On Jan. 2, Lifetime will premiere Surviving R. Kelly, Part II: The Reckoning, which details the aftermath of Part I — such as the slut-shaming, doxxing, accusations of lying, and death threats endured by the survivors who were interviewed for the series. Additionally, it includes shocking new allegations (including a claim by one woman that she had a suicide pact with Kelly) and heartbreaking new testimony about Kelly’s alleged sexual misconduct from his former hair-braider and confidant, Lanita Carter. DeRogatis also appears as “the world’s foremost scholar of R. Kelly interviews,” and courthouse press conference footage of him lashing out at Kelly attorney Steve Greenberg, as seen at the 8:23 mark below, is featured in a memorable segment.

As of this writing, Kelly remains in federal custody in Chicago; in April 2020, he is scheduled to stand trial on 13 federal charges related to child pornography and obstruction of justice. In addition, he faces 26 other state and federal counts related to criminal sexual abuse, sexual exploitation of a child, and racketeering. It will be interesting to see if the singer is finally brought to justice in the new year, and if the music business will finally have its true #MeToo moment. DeRogatis recently spoke at length with Yahoo Entertainment for a year-end interview about the state of R. Kelly in 2019, the increasingly difficult concept of separating art from its problematic artist, “cancel culture,” the backlash against the Kelly survivors that spoke out, and why it’s so important to listen to those women — and to women in general.

Yahoo Entertainment: It has been theorized that in 2019, the music world had its #MeToo reckoning, with Surviving R. Kelly and Soulless as well as with Michael Jackson and Leaving Neverland. But others say that nothing is really going to change. Michael is obviously long gone, but where do you think we stand with R. Kelly now?

Jim DeRogatis: Well, the thing that people who have devoted our lives to popular music are going to have to grapple with for the rest of our lives, in general, is this question: Is there something about this art form [music] in particular that has made it an ideal preying ground for some of the worst predators in the history of entertainment? Because let's face it, men have been treating women exceedingly badly in popular music from well before Frank Sinatra to way after Ryan Adams. But Kelly in particular — and I think that this still hasn't sunk in for a lot of people — he’s the worst predator in the history of popular music. He sits in jail now facing two federal sets of charges, with trials upcoming: a trial in Illinois and trial in Minnesota, plus Lord knows whatever else. Charges are still being added. It was only a couple of weeks ago that the Aaliyah charge was added to the federal indictment. He's looking at, by my count, 115 years in prison on 42 felony counts. Ain't nobody has had that amount of criminal activity, or some of the particulars. Nobody in the history of pop music has been charged with racketeering like a mob boss or the head of a drug cartel. So this is singular.

And how is this contributing to the national #MeToo conversation, would you say?

Well, as a critic, as a pop-culture zeitgeist observer, and the very fact that you asked the question, says you're seeing the same thing: I don't think the Kelly case has had nearly the same impact as Harvey Weinstein or Jeffrey Epstein.

And why do you think that is?

Oh, I know why. It comes from having talked to a 100 women for my book, 48 women whose lives were ruined by that man. And they say nobody matters less in our society than young black girls. So we have this double-whammy of nobody considering young black girls to be victims, and a predominant superstar in the black community. Aside from what I call in the book “the year of indie outreach” — Pitchfork, Bonnaroo, Coachella, the hipsters embracing Kelly as super-sexualized kitsch in 2013 — he has primarily been a black superstar. Bill Cosby was everybody's befuddled, lovable dad. Michael Jackson was everybody's biggest pop star of all time. Kelly's a black superstar. I don't even think he crossed the boundaries, with notable exceptions like “I Believe I Can Fly,” like a Marvin Gaye or a Donny Hathaway did. Kelly is a black superstar, and I think that that's part of it, because his victims were mostly black — and all women of color. I think that is significant.

You know, I'm a big boy. I'm a journalist. Thick skin, right? So I'm not talking about the hate I've gotten, although there's been plenty of it. But the women who were brave enough to do the hardest thing any woman can do, which is to rip out her soul and talk about her sexual abuse at the hands of a rich, powerful, famous, and beloved man… the hate that they are getting for having done, both with me and through Surviving R. Kelly with Dream Hampton, is unconscionable. So, related to what I said before, one of the questions that's really eating away at me is, is there something about R. Kelly music that not only ignores, not only condones, but perhaps even champions this kind of predatory behavior? I mean, at one point, Carey Kelly, one of Kelly's two half-brothers, said to me, "You got to realize, Jim, that the s*** he's talking about, he's talking to mother***ers on their level." He meant that R. Kelly is [singing] to other predators.

But do you think 2020 is the year when R. Kelly is finally brought to justice — meaning literally, in a court of law?

Well, no. I think that this is going to drag on for years. The two federal cases are exceedingly complicated. From the Eastern District of New York and Brooklyn and Chicago, they have not been consolidated. There's a complicated case of four victims the state of Illinois brought, and there's a case the state of Minnesota brought with one victim. I think it's going to be years as this winds its way through trial. So far, he is too stupid to take a plea. I don't think he ever will. So this will drag on for years, until fewer and fewer and fewer people care. But he's never going to breathe fresh air again. He's never getting out of jail. He's been denied bond on federal cases and the Illinois case, and haven't even been arraigned yet on the Minnesota case. The horrible details and the little fascinating, weird sidelights, all of that will eke out over months and then years, and he'll never be free again. Fewer and fewer people will care. Then 48 women whose names I know will continue to say what those I've spoken to have said, which is, all of this is too little, too late.

I must say, I am surprised about how it seems like the initial shock from both Surviving R. Kelly and Leaving Neverland has already subsided, after dominating the news cycle earlier this year. I even wonder if people will even care when Surviving R. Kelly, Part II comes out.

It might not make a difference. I think now we're at the death of outrage. It's like nothing gets us upset anymore, as long as we have our goddamn cell phone. Whatever media device, just plug in. Here we are now, entertain us. So, there's two things at play. There's the fact that a lot of people have never taken music very seriously beyond “this gives me pleasure right now.” Then there's those of music fans who do take it seriously, who are conflicted and are thinking about this. But things also change. I mean, I never thought I'd see gay marriage legalized, and I never thought I would see society make pariahs out of anybody who continues to smoke — just to cite two social examples. So maybe one day, we’ll be sitting around saying, “Can you believe there was ever a question that people felt they shouldn't listen to R. Kelly?” He may be written out of the books. Or, all this may be forgotten.

But please note that in the wake of all the federal indictments, Kelly’s Spotify numbers went through the roof. So more people than ever are listening to him. I don't think that's played out. [Sony may have dropped Kelly, but continues to distribute and market his catalog.] You're asking the wrong guy. I mean, I've been shouting about this since November 2000. Beats the f*** out of me.

On that note, should R. Kelly’s music be cancelled? Should his songs be banned from the clubs, from radio? What if a DJ spins “Ignition” or another one of his hits in the club? What if a wedding band plays a Kelly cover at a reception? How should we react?

I think one of the greatest thinkers on the nature of art, Oscar Wilde, was himself exceedingly conflicted about this [idea of art vs. artist]. Oscar Wilde, on the one hand, said that there is no such thing as a moral or immoral book. It is merely good or bad. But on the other hand, Oscar Wilde said some part of the moral core of a man is present in whatever art he creates. So some part of the evil of Michael Jackson that pursued underage boys is in his music. Some part of the evil of Kelly is in his music. That having been said, this is the debate in academia, largely being led by black men, condemning “cancel culture”: You shouldn't “cancel” Michael Jackson. You shouldn't “cancel” R. Kelly. But I don't see it as cancellation. They're trying to put it in terms of censorship. I see it as a consumer choice. What the #MuteRKelly women or [activists] Oronike Odeleye and Kenyette Tisha Barnes started was a movement saying: “Do not give your dollars to a man who preys on our daughters.”

So, I think there's no right or wrong in art, and I certainly am adamantly opposed to any censorship. But I do think if art matters, and it certainly matters to me, you should be aware of the context. If you are aware that no one in the history of popular music has ever faced criminal sexual abuse chargers as radical as R. Kelly, yet you can still take pleasure from “Ignition,” I can't condemn you. But I also can't condemn the person at the wedding who may also step forward and say, "Would you take this off the turntable, Mr. DJ?,” or walk out of the room.

But I don't think you're wrong if you can still bear to listen to “Ignition,” because such is the unique power of music — that it is now your song, and it’s as much yours as it's that son of a bitch's. Music gets in our soul. If “Ignition” has played at every backyard barbecue you've ever been to, if “I Believe I Can Fly” was your kid's kindergarten graduation song, if “Step in the Name of Love” was played at your wedding, then you own that song as much as that evil mother***er does. I'm not telling you to write those songs out of your history. You own them now. But I am saying you've got to know what this monster did to the black community. … With R. Kelly the bulk of his entire catalog is him singing about a sexuality which has now, I believe, been proven beyond shadow of a doubt for him is about preying on underage girls. The songs that aren't about that are about “Lord, forgive me for my sins” — which he's never named, but we now know what those sins actually were.

R. Kelly seemed to have a certain type of victim…

Yeah. Demetrius Smith, his road manager, he told me that night after night after night, there'd be 20 stunning women in the back room at Kelly's concerts, all half-naked and all about 22 years old, willing to do anything for him, with him. But night after night after night, there’d be a shy, acne-plagued teen, 14, 15, 16, in the corner, staring at her shoes, too shy to talk to anybody. And night after night after night, that was who R. Kelly went after. He knew the girls who would break down easiest. He had this sort of sixth sense, as many predators do. He knew who the victim was: people that may have problem situations at home, people who have poverty, people who were eager to sing.

Related to that last point, maybe young girls who thought he could make them the “next Aaliyah.” Which is sadly ironic, obviously.

That's one of the biggest tragedies. Tiffany Hawkins, victim No. 1, had a voice like an angel. From the south side of Chicago, she and her two best friends — also incredibly talented singers, 15 years old — traveled for work, and they saw Paris, Rome, Amsterdam, London, singing behind their best friend, Aaliyah. Every single one of those 15-year-olds he preyed upon, I think a good 40 of his 48 victims, were aspiring singers with incredible talent. And none of them ever made music. He never allowed any of them to make music. He preyed on their desire to make music, and to become the next Aaliyah, and then he killed that dream.

But, just to play devil’s advocate, there are many people who blame those girls, or the girls’ supposedly careerist parents, for letting their American Idol-like dreams of stardom cloud their judgment. Like, “Why did you go to his studio?” Or “Why did you let your kid go on tour with him?” That sort of thing.

I completely understand what you're saying. But again, think about race. Did we ever say of JonBenét Ramsey's parents, “How dare you let your toddler dress up like a sexpot?” I don’t know if we would similarly question the legions of white mommies and daddies out there who are willing to do anything to get their daughter in a Broadway show, to get their daughter a shot at pop stardom, to get their daughter on some runway in a fashion show. I think poverty in the black community plays into all of this.

Again, not to excuse R. Kelly’s behavior in any way, but I did think it was interesting that a lot of people in your book, instead of saying Kelly needed to be locked up, they’d say things like “He’s sick” or “He needs help” or “He needs therapy.” There's a lot more awareness and empathy for mental health issues than there was in the ‘90s or early 2000s. So I'm wondering if you agree with that, and if you think if he’d had that kind of intervention at some point in his life, maybe these tragedies could have been prevented? Maybe he never would have done these things?

This is a question that takes me far out of my depth as a music journalist and a music critic, but I'll turn to what I learned from experts that I talked to. They say that the vast majority of childhood abuse victims go the path of becoming advocates and champions of abuse victims in the future. The way that they cope it, to process it, is to try to protect others. A small percentage become abusers themselves. Now, I empathize with the weird, torturous upbringing and abuse that Kelly suffered from men and women in his childhood. I detail that at great length. [Both R. Kelly and his half-brother Carey have claimed they were repeatedly sexually abused as children.] But then I realize the number of wakeup calls. The Aaliyah thing blowing up, which he dodged until three weeks ago when it's subject to a federal indictment. The first lawsuit by Tiffany Hawkins. The second and third by Tracy Sampson and Patrice Jones, and then Montina Woods. Then the indictment for making child pornography, and then the trial [in 2002].

During the [2002] trial, he was seeing the top black psychiatrist in Chicago, being treated for his abuse and his trauma, and taking testosterone-killing drugs — essentially becoming de-gendered, neutered, with drugs throughout the trial. But the minute the trial was over, all of that was out the window. In fact, before it was over, during the trial, he began pursuing 15-year-old Jerhonda Pace, who is now subject to federal and state indictment as one of 12 new victims. So what I am trying to say is, how many times did he have the opportunity to turn his life around, and he just could not or would not stop? Therefore, I think empathy ends at a point. He had every break that dozens of people who've had similar horrifying trauma in their lives have never gotten.

On the subject of these crimes being prevented: At some point during your investigation, how many people who've worked with Kelly have come to you saying that they feel bad that they were complicit — that they either witnessed something, or knew something, or suspected something, and just turned a blind eye?

Dozens. Dozens. Dozens. Recording engineers, tape operators, record company publicists, radio promotion people, concert industry people, musicians — some of them quite famous, some of them studio musicians. Dozens of people.

Is there an overarching theme as to why these people did nothing?

I think it was always a power imbalance. These were people who were struggling to get ahead, to make ends meet, who stayed on board because they couldn't afford not to, until — and there was a different tipping point for every single person — finally they couldn't abide by what they saw any longer. Again, it's a question of power. One of the things that's fascinating to me about the Epstein story is ain't no f***ing way Prince Andrew didn't have a clue. And it’s hard to believe Alan Dershowitz or Bill Clinton or Donald Trump didn't have a clue as to what was going on [with Jeffrey Epstein]. It is impossible to believe that Clive Calder, the multi-multi-multi-millionaire founder of [Kelly’s label] Jive Records, was unaware of what Kelly was doing. So it's really hard to take the tape operator, who was going through hell in these 20-hour sessions, to task, when the head of the record company probably could have stopped it.

Why do you think it took so long even to get to this point with R. Kelly?

I think the reason Surviving connected, and Neverland connected as well, is America finally got to hear from these victims. For two decades, I was sitting one-on-one with young women, who often took years before they decided to go on the record and speak to me. I was having that experience, and Surviving gave America some semblance of that experience. Woman after woman after woman — they can't all be lying, right? But once again, I can only say in response to your question what they've all said to me: It's too little, too late. Just think that if he'd been convicted, Jerhonda would not have been heard, Azriel Clary would not have been heard, Joy Savage would not have been heard, Asante McGee would not have been heard, Kitty Jones would not have been heard, Halle Calhoun would not have been heard. Because those things wouldn’t have happened. It's like, wow — if Kelly had stopped when Tiffany Hawkins tried to stop him with the first lawsuit, the victim list would have been five of her best friends, who he preyed on at 15, and Aaliyah. And it would have ended there. But it didn't end. It never did. So there's no satisfaction. It’s just a horrible, tragic f***ing story, about music, this art form that I love, being used to ruin lives instead of lift us up.

As you mentioned before, this all goes well beyond any one artist, beyond R. Kelly or Michael Jackson or whoever. And you say that, historically, there’s been something intrinsically misogynist about popular music. But you’re a music superfan and a music historian, first and foremost. You’ve touched on this a bit already, but where do you stand on the whole separating-the-art-from-the artist debate in general?

There's a book by a group of British academic women called Under My Thumb: Music That Hates Women and the Women Who Love It. It deals with everything from the Rolling Stones to Eminem. And I wonder if — unlike film, unlike theater, unlike visual art — is there something inherent in music that lets us embrace the taboo, the evil? Forget about R. Kelly, forget about Michael Jackson. Have you listened to “Brown Sugar” lately? The Stones are 70 years old, on tour charging $650 for halfway-decent seats, and they're still singing this song about the fantasies in the heads of slave owners. They’re still singing “Midnight Rambler,” fantasizing about being a sexual predator, rapist, serial killer, the Boston Strangler.

So for me, where my own personal dividing line is, is if the art is about the misdeeds, I can't condone it or listen to it or consume it. Fully 98 percent of the Rolling Stones’ catalog can still give me pleasure, but I can't listen to “Brown Sugar,” and I can't listen to “Midnight Rambler.” I can listen to all Michael Jackson and still take pleasure from it, up to but not including the last two albums. The last two albums are full of those songs like “All the Lost Children,” where Jackson is putting himself as a savior of children, or “D.S.,” where he's taking on by slightly altered name the prosecutor in Santa Barbara County who tried him, where he's saying, “Media, you tried to crucify me like you crucified the Lord.” No, I am not down with that.

Yes, but many people would say some songs, like the Stones ones for instance, have to be considered within the context of when they came out. “It was a different time” or whatever.

I don't think there's one answer here. I think every single one of us as individuals has to consider where the lines are. I don't think there is any wrong or right in art. I think there is only the obligation of us to think about it. So perhaps the reconsideration of some Zeppelin songs, of some Motley Crue songs, whoever’s songs, is long overdue. And that conversation is being had. I'm not going to condemn someone for continuing to listen and laugh at Eminem's many songs fantasizing about murdering his wife Kim, but I can't listen to them. They turned my stomach when I first heard them. “Find'em, F***'em, and Flee” and “To Kill a Ho” on the second N.W.A album turned my stomach when I first heard them in 1991. I think it took me a couple of years before I really realized what “Brown Sugar” was about, and now, at least since 1990, I have not been able to listen to that song. I don't want to impose a moral litmus test on art. But I will not give a pass.

So everything that you just said, when people are saying you got to put it in context, I say [to those artists], “F*** you and bulls***. Your ‘context’ at the time was you were a scumbag. You did not respect women, and portrayed it in song, and I don't want to hear it.” Because at the same time that s*** is happening, we have Joan Jett. At the same time Led Zeppelin is happening, we have Heart. We have always had the sex-positive, female-positive alternative. Nirvana's Nevermind had not yet come out when we saw Dr. Anita Hill torn apart in full view of the world and Clarence Thomas put on the Supreme Court, and here we are today, after the conversation has started, with Dr. Blasey Ford getting torn apart in full view of the world and Brett Kavanaugh put on the Supreme Court. But I still think of Cobain saying towards the end of his life in his journals, “The future of music belongs to women.”

And I think the music that will stand is the stuff that was about liberation for all of us and empowerment for all of us, and the celebration of all of our desire to be respected as individuals and for our unique individuality. I think that as I look at it now, the favorite art that I have — whether it's Wire, Savages, Public Enemy, Nirvana, or George Clinton and Funkadelic — is really about the celebration of the life force and this battle against nihilism. Nihilism to me includes sexism and any of the “isms” that people of power will use to put everybody with conscience down.

The R. Kelly story has taken up almost a third of your life, and more than half of your professional life. What is the thing about this case that sticks with you the most, that haunts you the most?

There are bits and pieces of everyone's story. Lizzette Martinez being half a country from home in Chicago, left alone to miscarry at 17 in a hotel room — this Miami girl, a beautiful singer, who never sang again. Or Jerhonda, being such a fan that she was attending the trial, and then finding out what he really was [when he pursued and abused her as well]. All of those stories haunt me.

But I think my book opens really with Tiffany Hawkins. If her name had not been in a fax that I got on the Wednesday before Thanksgiving 2000, I would have never started down this path of telling this story. Then having had the privilege of finally meeting her in January 2019, when Surviving R. Kelly had just aired — I remembered that on Dec. 21, 2000, I had put her name in a daily newspaper, because we were reporting what had happened to her [in 1991]. She had refused to talk [in 2000], and her parents refused to talk. I said to her [in 2019], "That must have been a s***ty day for you," and she said, "No. I was glad you did it. It had to be done. Thank you." That's really overwhelming to me. But then also to think that this girl with the voice of an angel singing in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Rome, and then never singing again... I once asked her, "Tiffany, can you even listen to music?" And she told me, "No. I can't take any joy from music anymore." The book ends that way. To me, it's an investigative story. It's a story about journalism. It's a story about culture. It's a story about #MeToo. But I'm a f***ing music-lover at the end of the day. So that line really sticks with me.

Obviously you did not bring down R. Kelly singlehandedly, but your reporting had a hand in it. What do you think your specific contribution was to the cause?

Well, for a fat, clueless guy from New Jersey, who is hardly the epitome of “woke,” or wasn't for many years, all I can say is: I listened. I listened to hundreds of black women who said, "No one's listening to me. I've been hurt. Can I tell you my story?" So the credit is on those women. If I deserve credit, it's just for the fact that I listened and told the stories. The stories have stood. Not a word has been corrected, clarified, retracted, or subject to lawsuit. I think the 42 felony counts and four indictments is pretty good vindication for a journalist, right? But it's about the women. If women hadn't trusted me to tell their story, and I don't think I have superpowers as a journalist in that regard.

I just think I shut up and listened and cared, and didn't give up. Because it would have been really easy to give up after the first story in December 2000, where nothing happened and in fact I was called a “racist” for trying to take down a successful black man, according to many in the Chicago black community. But again, that ain't nothing compared to the hate that these brave, extraordinary women get. Yes, some of them are flawed, and some of them have contradictions in their stories. That's called being a human being, OK? That is also rape culture vilifying them. Anyway, I think I have a voice. And I've tried to use that megaphone to amplify people who weren't being listened to.

I did an event in New York with Jamilah Lemieux, who I respect enormously as a culture critic, and Tarana Burke, who started #MeToo 16 years ago. And I'm thinking that sitting with [Burke] today has got to be what it was like to sit with Martin Luther King or Malcolm X in 1965. This is a worldwide civil rights reassessment that the entire history of humankind is overdue, and goddammit, bring it on. And to whatever extent I am a footnote for me listening to women and telling their stories, I'm happy to have done that.

(This conversation has been edited for clarity.)

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment:

'Surviving R. Kelly' filmmaker celebrates the singer's arrest: 'It's a wrap'

Where do we stand on Michael Jackson after 'Leaving Neverland'?

Follow Lyndsey on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Amazon, Tumblr, Spotify.