How Rap’s Elder Statesmen Took Over Podcasting, TV, and Everything Else

A chart mainstay and ferocious rhymer from the late-Nineties into the aughts, Queens rapper N.O.R.E. has since built a hugely visible (and lucrative) second career as a podcast host on Revolt’s Drink Champs, where he and DJ EFN swap stories and libations with the biggest names in rap. Their 2021 episode with Kanye West earned more than 12 million views on YouTube alone, dominating cultural discourse. This year, they’ve talked to MCs like Rick Ross, City Girls, and Kodak Black, as well as Bill Bellamy, Lyor Cohen, and Derek Jeter, broadening their focus beyond hip-hop culture.

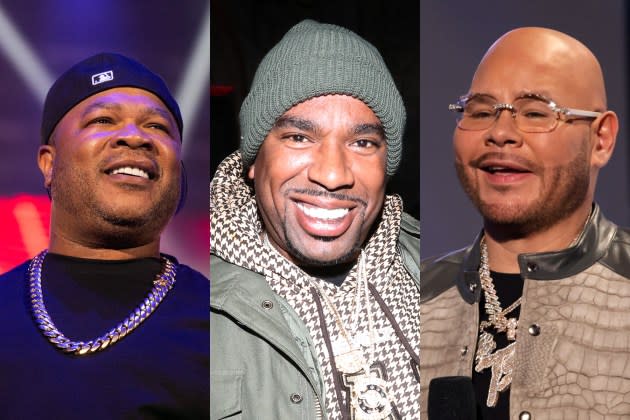

N.O.R.E. is hardly the only legacy rap act to find success as a media personality, either. He’s part of a class that includes Joe Budden, Fat Joe, Xzibit, Remy Ma, and Trick Daddy, who have all found fame hosting podcasts, TV series, and everything in between, routinely creating viral moments. One of the dominant storylines around Drake’s album For All the Dogs, for example, was his war of words with Budden, whose criticism of the LP prompted the biggest rapper in the world to respond at length on social media.

More from Rolling Stone

N.O.R.E. first found success on traditional airwaves with Militainment Crazy Raw Radio on XM Radio. Over Zoom, he explained that the only reason MCR ended and Drink Champs was born was because the then-newly formed Sirius XM insisted the series broadcast from New York. “Who’s to say? If Sirius and XM never merged, Drink Champs might’ve never existed,” he says.

For Fat Joe, the decision to get into the rap-media game came in 2013, when he wound up serving several months in prison for tax evasion. “When I went to jail, I realized that I had to take life seriously and diversify,” Fat Joe says. “And so when I came out, I opened some sneaker stores and clothing stores, and just got into a whole bunch of different kinds of business.”

Joe has become a major player in the media space, receiving a pilot order for an interview show on Starz last September, as well as guest-hosting The Wendy Williams Show alongside longtime collaborator Remy Ma in 2021, and several more times last year. Joe’s capitalized on his love of basketball by becoming Streetball commissioner for the sports streaming platform ClashTV. (Ma has maybe the most outside-the-box gig, as the narrator of VH1’s docuseries My True Crime Story.) In classic Joe fashion, he likens his generation’s transition to what we’ve seen from erstwhile NBA stars. “It’s no different than Isaiah Thomas, Shaquille O’Neal. These are legends in the basketball game, and now we watch them on TNT every day,” he says. “It’s a natural progression of hip-hop to get the guys that have been doing it, and the girls that have been doing it to cover it now.”

The basketball metaphor is particularly relevant for Mase and Cam’Ron, who reportedly signed an eight-figure deal for their sports-centric talk show It Is What It Is. The program is another instance of New York MCs finding success by letting their bombastic personalities shine, and it continually spawns viral moments that break out of the sports and hip-hop social media bubbles.

Unsurprisingly, many of the rappers who have found success in other lanes of entertainment also have experience acting. The most common alternative creative lane for MCs, film and TV roles have been massive for artists like Queen Latifah, Ice Cube, and Snoop Dogg. But Hollywood doesn’t give artists the same room for personal expression as podcasts and talk shows. In the past, rappers have often had to choose between reductive roles as street toughs (Dr. Dre in Training Day), acting in underseen indie flicks (Freddie Gibbs in Down With the King), or assembling their own projects outside of the traditional industry system, which makes finding a wider audience challenging (how many die-hard Lil Wayne fans have seen the 2000 Cash Money film Baller Blockin’?). N.O.R.E.’s film career never rivaled Snoop’s or Xzibit’s, but he credits that reinvention, as well as a mid-2000s pivot to Spanish-language hip-hop, with making him creatively malleable.

“I like to say [podcasting] is my third career, because I feel like reggaeton and the movies for a little while were probably my second career,” N.O.R.E. explains. “I don’t want to say it’s easy, because it’s not easy, but there are things about it that are way easier than being a rapper.

Hip-hop is often said to be a young person’s game, and as the genre hits its 50th anniversary, more artists than ever are grappling with how to stay successful when the popular sound moves at the speed of the internet. In his most recent, widely-discussed interview, André 3000, 48, said that it “sometimes feels inauthentic” for him to rap at this stage of his life, citing what he sees as a lack of compelling subject matter. (Some A-list artists have stressed that they feel differently than the Outkast member, including fellow 40-plus-club member Lil Wayne, who said, “I feel like I have everything to talk about [in my music].”) Besides releasing his flute album, André is one of the rappers who has turned to film, appearing in a variety of critically acclaimed indie movies, including High Life, Showing Up, and White Noise.

Xzibit, who pioneered transitioning from a rap career to television with Pimp My Ride in 2004, describes how the attitude around rappers going on TV and acting in commercials has changed in the past 20 years. “You were considered selling out when you did Pepsi commercials like MC Hammer. It was frowned upon. But now, it’s like you’re dying to be on a reality show. You’re dying to be on Love & Hip Hop,” he explains. “The new artists want to be seen for everything and accepted for everything, except the music sometimes.”

Xzibit has lived several lives beyond his musical career — in addition to Pimp My Ride, he played the heavy in Werner Herzog’s Bad Lieutenant and shined in a lead role in the 2017 indie comedy Sun Dogs. Now, he’s joining N.O.R.E. in the podcast sector with Lasagna Ganja, a cannabis series that he co-hosts alongside Tammy Pettigrew. Prior to launching the show, he had been involved in the marijuana industry with Napalm Cannabis, a company named after his 2012 album that was mired in controversy due to napalm’s use in the Vietnam War.

Though artists like Xzibit, Fat Joe, and Cam’Ron all have their share of platinum and gold plaques, they’re not the kinds of musicians who reap the rewards of the streaming economy. Their most iconic work is decades old, less likely to be included in high-traffic playlists, and the money from pure music sales seems like an inconsistent bet. Much like professional sports, music can be a cutthroat industry, one that doesn’t encourage frugality, and can leave the stars of yesteryear in bad straits. Trick Daddy has been transparent about his financial struggles, and peers like the late DMX and former G-Unit star Young Buck have faced similar issues as their reign atop the charts came to a close.

Nostalgia has become its own cottage industry within rock music. However, hip-hop’s history of battling discrimination, exploitative contracts, and ill-intended stereotypes means that we’re still a ways away from that level of pop-culture saturation and the opportunities it brings for legacy acts. Rap remains an industry driven largely by new talent, but the A-listers of the 2000s are showing that success in hip-hop can be spun into all sorts of opportunities that make your identity as an MC an asset.

“[We’re] showing [younger artists] that there’s life after your twenties and thirties, and you could do it successfully,” Joe says. ”Prior to us, nobody was really doing it like this. So this era has been a breakout era for many things as far as equity, entrepreneurship, and ownership.”

Best of Rolling Stone