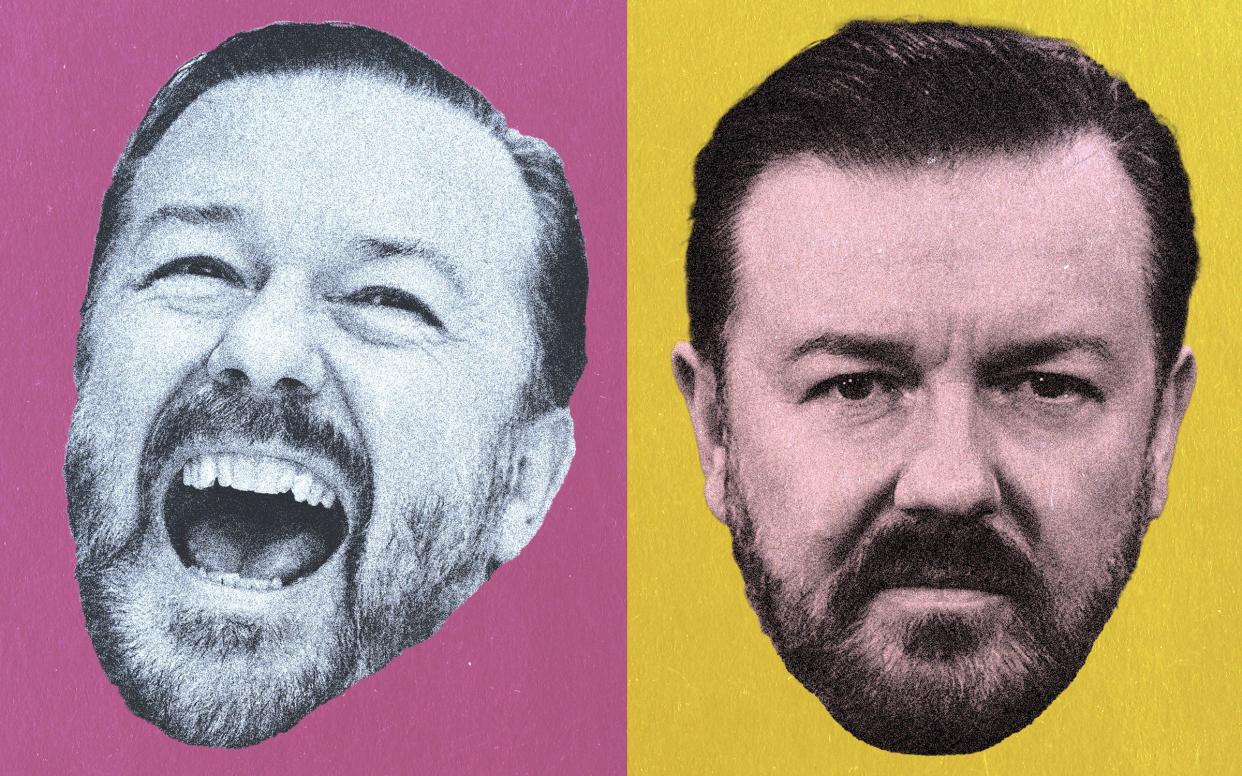

Ricky Gervais has become an anti-woke champion – but is it just his latest act?

He supported Jeremy Corbyn and is a vegan and animal welfare champion who once said: “You can’t take equality ‘too far’.” But, in recent years, Ricky Gervais has built up a legion of Right-wing fans for his insistence on saying “the unsayable” about woke culture.

In a succession of stand-up comedy tours, all later broadcast by Netflix, the creator of The Office has been in equal parts lauded and denounced for jokes about cancel culture, transgender politics and Gen Z snowflakes.

Fellow comedian Robin Ince, who this week claimed he was once bullied so badly by Gervais that it triggered a “stress rash”, has gone so far as to describe his former collaborator as a “pin-up and role model for the alt-Right”. Thanks to his “anti-trans punchlines”, Gervais has become “a useful ally in the culture war”, he said in an essay on his website in 2022. The two men have not spoken since.

But while Gervais’s surge in popularity among the anti-woke has certainly done his bank balance no harm (his most recent Netflix film, Armageddon, is the highest-grossing comedy special of all time), it is by no means clear that he welcomes his new hero status.

This week, for example, Gervais will have been horrified to learn that an Australian man, in court for performing a Nazi salute outside a Jewish museum in Sydney, cited him as an inspiration, quoting from a routine in which Gervais joked about a schoolboy called Adolf raising his arm in Hitler-fashion when his name was called out at registration.

The Australian case neatly captures the paradox of the modern Gervais. To his supporters, Gervais – like Jimmy Carr or Dave Chappelle – is a free speech champion slaying the shibboleths of woke culture. To his detractors, including some fellow comics, the 63-year-old is a heretic whose best days passed after The Office ended and who now “punches down” against disadvantaged minorities solely because he’s an attention-seeker.

Gervais himself rejects the Right-wing label. “I’m an old-fashioned liberal-Leftie, champagne socialist type of guy. A pro-equality, opportunity-for-all, welfare state snowflake,” he wrote on Twitter in 2019. “But, if I ever defend freedom of speech on here, I’m suddenly an alt-Right Nazi. How did that happen?”

How indeed? Gervais came relatively late to stand-up, with his first UK-wide tour in 2003 (well after The Office became a hit), and his pre-existing fame probably meant he was more willing to push the limits of taste and decency than those who slogged across the circuit in their 20s. His five stints hosting the Golden Globes have gone down in Hollywood lore, with Gervais being gratuitously rude and blasting Tinseltown’s elite for their general sanctimony. “You’re in no position to lecture the public about anything,” he said in 2020. “So if you win, come up, accept your little award, thank your agent, and your God and f— off, OK?”

As well as jokes about political correctness, he has also targeted the disabled and the mentally ill and made gags about paedophilia. Unusually for comedy, an industry where an unspoken code holds that you don’t explicitly attack your fellow practitioners, Gervais has come under fire from the likes of Nish Kumar, James Acaster and Stewart Lee. “What he’s doing is not edgy or interesting. He seems to think that it makes him an edgy or interesting comedian, it’s not,” Kumar said in a 2018 routine. “All he is is just the same as every other rich, white dude comedian who gets too successful, runs out of ideas, and so just s---s on the latest minority group.”

Lee continued what has become a rather one-sided feud in an interview with Prospect magazine last week. “It’s disingenuous. You get people saying they can’t say anything. But a lot of them are filling stadiums, winning Grammys, and getting $60 million off Netflix,” he said. “Ricky Gervais would love to be properly ‘cancelled’, I think, but he doesn’t seem able to say anything actually controversial enough to be as controversial as he’d like to be.”

The truth is, both those who adore and loathe Gervais for what he says on stage are missing the point entirely. “I’m nobody’s champion,” he once said. “‘Get a better champion’ is what I’d say to anybody who thinks I’m their champion.”

What appears to preoccupy Gervais more than anything is the right to free speech – and to offend. “There’s nothing you shouldn’t joke about, there’s no subject you shouldn’t joke about. It depends on the actual joke and the target,” he told American talk-show host Stephen Colbert in 2019. “People get offended when they mistake the subject of a joke for the actual target and they’re not necessarily the same.”

Born in Reading to working-class parents (his father was a labourer while his mother did odd jobs and brought up four children) Gervais may reflect that whatever he has done in his career has worked. He owns mansions in Hampstead, north London, and Marlow, Buckinghamshire, and now owns the Dutch Barn Vodka brand.

Armageddon, which debuted on Christmas Day last year, won a Golden Globe. Next week, Gervais kicks off Mortality, a new stand-up set that will also be filmed for Netflix, in London’s West End. People who love to love, or love to hate him, will have plenty to rake over.

“We’re all gonna die. May as well have a laugh about it,” he said. “Mortality looks at the absurdities of life. And death. Bring it on.”