The Riot Grrrl Who Named Nirvana’s Biggest Song Tells All

Kathleen Hanna has never been one to mince words, so why would she start now?

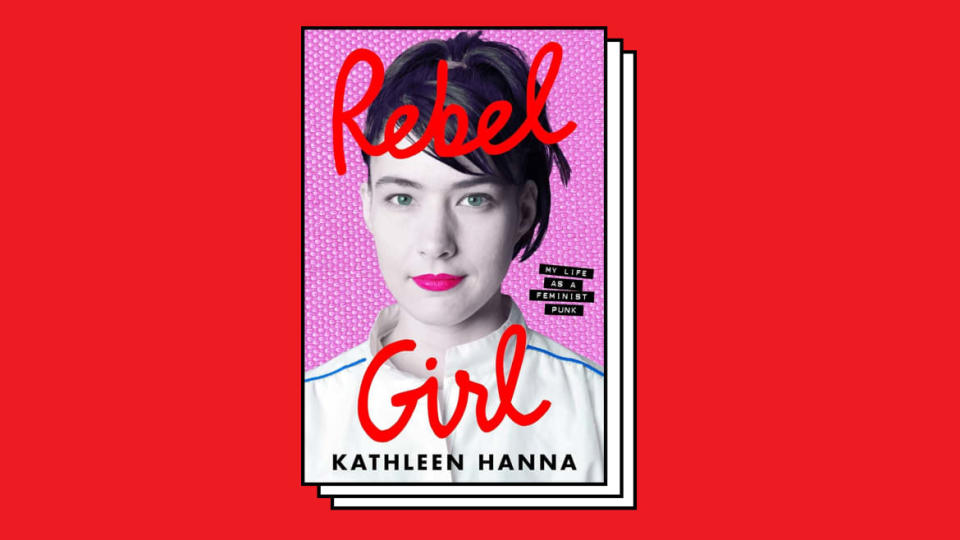

The punk-rock trailblazer’s memoir, Rebel Girl: My Life as a Feminist Punk, arrives on Tuesday and finds Hanna writing both searingly about men who abused her, and humorously about everything from clueless record execs to her friend Kurt Cobain. Along the way, she traces her life from her difficult childhood growing up with a sadistic and alcoholic father, to her ’90s notoriety as the front woman of Bikini Kill, the punk outfit that spearheaded the third-wave feminist movement known as Riot grrrl. The 55-year-old artist also gives rare insight into her diagnosis of late-stage Lyme disease that sidelined her for years, as well as her marriage to a Beastie Boy.

Below, read about some of the book’s best bits, from the stories of how she coined the phrases “girl power” and “smells like Teen Spirit” to that infamous confrontation with Courtney Love.

Her sister’s scary overdose taught her about the dark side of fame.

When Hanna’s older sister was in junior high, she accidentally overdosed on jimsonweed, a poisonous plant that, if taken in high doses, can be deadly. Her sister was in a weeks-long coma, during which Hanna discovered what being “famous in a bad way” was like, as her peers needled her and spread rumors about her sister having died (she didn’t).

“Looking back on it now, I realize I got a lot of unwanted media training during that time,” Hanna wrote. “I learned that people love to attach themselves to fame even if it involves disaster, and that journalists are not always accurate.”

Getting an abortion when she was a teenager involved a cross-country flight and an essay-writing “contest” of sorts.

Hanna got pregnant when she was in high school, but the ex who’d impregnated her, Trent, refused to help her pay for an abortion. Not wanting her mom to find out about her pregnancy, Hanna got a plane ticket to Virginia, where her sister lived, and got a job at McDonalds to make the money she’d need for the procedure.

“I was nearing the end of my first trimester, which meant I had to get an abortion right away or it would be illegal,” Hanna writes. “I knew if I had a baby it might have a lot of problems, since I’d smoked so much pot and done so much acid.”

Once at the clinic with the money she needed, Hanna had to write an essay about why she was mature enough to make the decision to get an abortion on her own, since she was under 18 at the time.

“I came in scared about having an abortion and now I was writing an essay begging for one… I wrote that I wanted to take responsibility for my own mistake by not bringing an unwanted person into the world who I couldn’t care for. There was no need to bring shame on my family; it was all my fault. It was like an essay contest where the prize is you don’t have to have a baby. I sounded pathetic and sad and stoic, which I guess worked because I WON AN ABORTION.”

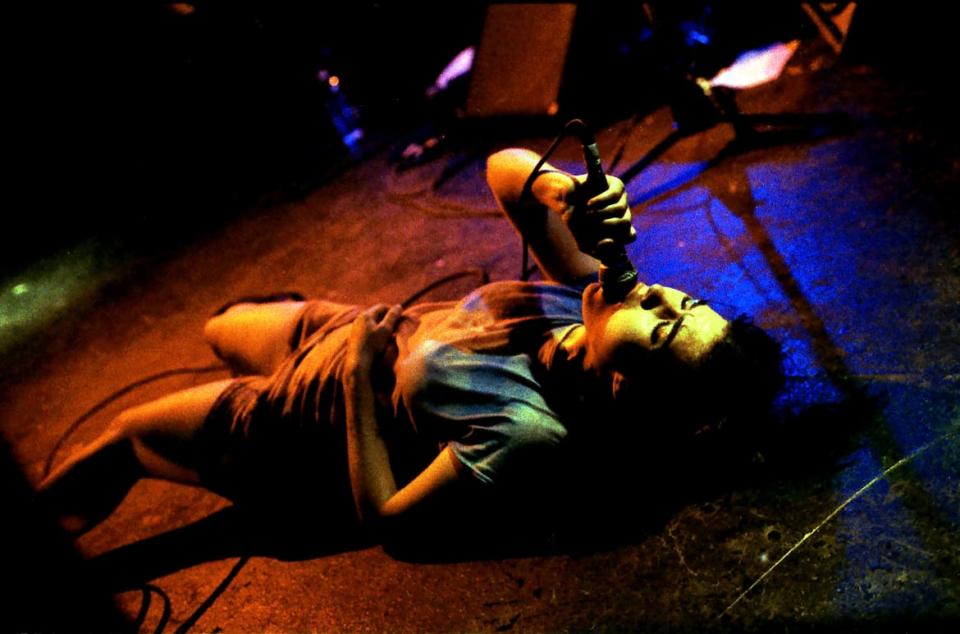

Kathleen Hanna lies on her back on stage as she performs in Bikini Kill at the Las Palmas Theatre in Hollywood on November 18, 1994 in Los Angeles.

She writes humorously about getting a job at a strip club to pay for school.

To pay for her tuition at Evergreen State College in Olympia, Washington, Hanna got a job at a strip club and started dancing to the only two cassettes she owned at the time: Tracy Chapman’s self-titled debut album and Janet Jackson’s Control.

“I stood in front of a full-length mirror in my friend’s rented room and practiced bouncing my butt up and down while being reminded ‘It’s Janet... Ms. Jackson if you’re nasty.’ When I got bored of that cassette, I tried dancing to ‘Mountain o’ Things’ and ‘Fast Car,’ but it was pretty impossible to do butt jiggles to Tracy Chapman songs.”

“But,” Hanna adds later, “it was all worth it when I walked into the Evergreen office at the start of my junior year and paid my tuition with a lunchbox full of twenty-dollar bills.”

She writes glowingly of her friendship with Kurt Cobain.

Hanna befriended the eventual Nirvana frontman through the Washington punk scene and through her Bikini Kill bandmate Tobi Vail, who dated Cobain for a time.

“I wasn’t attracted to Kurt, but he definitely glowed. Like he had sounds bouncing off his skin,” Hanna writes.

Cobain also stood up for Hanna against a nasty ex-boyfriend named Luke, who would frequently show up at her apartment unannounced after they broke up, seemingly to intimidate her.

“Kurt’s apartment became my escape hatch over time. The bubble I wrapped myself in to get away from Luke. Kurt used to joke that we were brother and sister and the Brawny paper towel guy was our dad. We would smoke pot while watching his turtle walk around his tiny living room. He was the first feminist man I ever met who never thought being an ally meant you couldn’t defend a woman in bold strokes because she was supposed to do it all for herself. He never even flinched.”

Kurt Cobain’s Daughter Shares Moving Tribute to Her ‘Transcendent’ Dad

Yes, she came up with the phrase “Smells like teen spirit.”

One night at Cobain’s apartment, Hanna recalls, the two “went on a rampage, drunkenly destroying everything.”

“I scribbled endless shit above his bed with the Sharpie from my back pocket: ‘Kurt is the keeper of the kennel... Kurt smells like Teen Spirit,’” she continues. “Earlier in the day, Tobi and I had been at the local supermarket looking at deodorants, and we both laughed hysterically when we saw one called Teen Spirit. What the fuck does teen spirit smell like? we wondered. Capitalism apparently knew no bounds.”

A few months later, Cobain called her asking if he could use the line “smells like Teen Spirit” in a song (the one that, of course, would go on to become Nirvana’s most iconic hit).

“I just said, ‘Sure,’ thinking it was no big deal,” Hanna writes.

She and her Bikini Kill bandmates did, however, decline Cobain’s invitation to appear in the “Smells Like Teen Spirit” music video as anarchist cheerleaders.

“I responded with a HARD NO, because I wanted our band to be judged by the misogynist ‘meritocracy’ of the time, not through the lens of association with an all-male band,” Hanna writes. “Tobi, Kathi, and I talked about it and decided to decline.”

To her horror, she once had to strip to “Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

People in the punk scene eventually found out about the strip club where Hanna worked as a dancer, and she recalls one embarrassing night when “a well-known scenester” named Shelby and her boyfriend showed up to the club. The dancers had to dance to whatever song someone put on the jukebox, Hanna recalled, and a certain someone cued up the Nirvana hit she had helped name.

“When ‘Smells Like Teen Spirit’ started to play, I twirled along to Dave’s drum intro with a fake smile plastered on my face, hiding a sense of humiliation too deep to describe,” Hanna remembers. “Shelby and her boyfriend were laughing. I’m sure it was hi-larious. I was taking my clothes off to a song I’d written the title to. Kurt was on his way to being a multimillionaire while I was jiggling my ass in a broke-down strip club. Hahaha.”

Bikini Kill started performing in their pajamas to send a message about sexism.

Around 1992, Hanna recalls, the mainstream media was writing a lot about Bikini Kill—but not always in a flattering or even accurate way.

“Spin wrote that I bared my breasts at every show (not true), and most articles claimed we hated men because we were not like normal girls and had suffered an extreme amount of abuse. Journalists, even women, would write about our bodies and our clothes but never our songs.”

To combat that, the band decided to send a sartorially powerful message from the stage.

“Tobi decided that going forward, we should just tour in our pajamas so everyone would leave us the fuck alone, and it worked,” Hanna writes. “Guys still yelled at me onstage, but at least I could go into a pharmacy by myself and no pervs would follow me around. I was in my pajamas in broad daylight carrying a handbag and was definitely not to be fucked with. My life felt so surreal by then that refusing to wear daytime clothes seemed like the only sane response.”

Hanna notes that the band performed in their PJs at a show in New York City that she’d invited Joan Jett to, after hearing the iconic rocker was a Bikini Kill fan. After the show, Jett told Hanna that she wanted to produce a record for the band.

“She didn’t even ask about the pajama thing. It was like she already knew.”

Bikini Kill had no patience for major label execs like Jimmy Iovine.

As Bikini Kill started getting more popular, their manager suggested they meet with major labels in L.A. Even though Hanna writes that no one in the band wanted to sign, they decided to have some meetings “as a joke.”

“When Kenny set them up, he told the labels that we had one request: the band would like to review the company’s sexual harassment policy,” Hanna writes, adding that they met with Lenny Waronker at Capitol Records, Jimmy Iovine at Interscope, and Mo Ostin at Warner Bros., and “not one of them had a sexual harassment policy ready for us when we arrived.”

The Interscope meeting, in particular, didn’t go well: “To show us how edgy Interscope was, Jimmy Iovine showed us a Marilyn Manson video that hadn’t come out yet. ‘You guys could do an edgy video like that!’ he said. ‘Could I hang you from a meat hook?’ I asked. Iovine pretended he hadn’t heard me and continued his spiel about how great his label was. Needless to say, we did not sign with Interscope.”

After Cobain died, she had a lot of regrets about their relationship—and a lot of anger toward the media.

In the last few years of Cobain’s life, he and Hanna didn’t see each other a lot; by then, he’d gotten married to Courtney Love, who Hanna notes had “been putting Bikini Kill down in the press for a while, so it felt like seeing him with her around was a bad idea.”

But she eventually decided to pay Cobain a visit in Seattle on a weekend when she knew Love wouldn’t be there.

“I hadn’t seen Kurt in ages, and I wasn’t sure he’d want to see me now. But I knew he was still doing heroin and wanted to at least let him know I cared about him and was there if he ever needed help, before it was too late,” Hanna writes. As she was packing up her car, though, she “chickened out.” “I thought: We aren’t close anymore. He has a whole new life. He’s in one of the most famous bands in the world! He probably doesn’t wanna see me.”

After Cobain’s death on April 5, 1994—he was found dead by suicide three days later—Hanna recalls feeling “physically ill” seeing photos of him everywhere she went.

“I felt like he had died at least partially because he was sick of being exploited and treated like an object, and now that he was gone people were lining up to make money off his suffering. His death made me more secure in my strategy of eschewing fame whenever possible and working toward things that actually mattered. I was having a hard time dealing with the minuscule amount of fame I had; I couldn’t imagine how he had lasted as long as he did. But more than anything I was sad. Sad about the heroin, about the gun, about his not having the happiness he deserved. Sad we would never be old together, sitting on a porch talking about when we were stupid young musicians who thought we could change the world.”

Most of all, though, she regretted not having paid him that visit.

“Why hadn’t I had the courage to go see him? To tell him I loved him and to reassure him that I in no way thought he was a bad person for signing to a major label? I was a fucking coward. Scared of Courtney. Scared of him rejecting me when he never had before.”

Punk Rock-Feminist Pioneer Kathleen Hanna On Her SXSW Doc & More

She gives her detailed account of her fight with Courtney Love.

In a chapter simply titled “The Courtney Thing,” Hanna writes about her infamous confrontation with Love at Lollapalooza in 1995. Her friend Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth told her she was “worried that Courtney Love might start shit with me. Courtney had gotten physical with Kurt’s former friends before, and Kim thought I might be next.”

“I needed a plan in case I did, so Kim and I came up with the sentence ‘I would be happy to debate you at the college of your choice.’ I figured if she yelled at me, I would just repeat it like a force field,” Hanna writes, adding that she’d never met Love until that point, but the Hole frontwoman had “gone to great lengths to insult me in interviews.”

As Hanna was watching Sonic Youth’s performance from backstage, someone started throwing candy at her head—and Hanna realized it was Love, now walking toward her.

“Courtney got in my face and started hissing like a cat and reaching out like she was going to claw me… She held her lit cigarette up to my face and traced my features with it, like she was going to put it out on my face. Then she dropped a sweater in front of me and bent down to grab it. As she stood up she coldcocked me in the face. I fell down, put my hand up to my cheek, and felt blood. From the ground I yelled, ‘I will debate you at the college of your choice!’ She yelled back something like, ‘You can’t even read, and I’m way more feminist than you!’”

“I’ll never know why she did it,” Hanna goes on. “Maybe because ‘trauma begets trauma.’ Maybe she was on drugs and mourning Kurt’s death; maybe it was the fact that Tobi had dated Kurt while he was writing Nevermind, and it was widely speculated that Tobi was the inspiration for much of that record. Maybe Courtney was embarrassed because I’d seen her using my stage banter as an empty schtick. Whatever set her off, it was ironic that a woman attacked me for no reason and then claimed she was a smarter, better feminist than I was.”

Months later, Hanna ran into Nirvana bassist Krist Novoselic in Los Angeles, and he gave her some much-needed reassurance. “‘Kurt would have been really upset to hear that someone hit you in the face. He loved you, I know he did,’” Hanna recalls the bassist telling her. “His kindness felt oversized and generous and was exactly what I needed.”

Kathleen Hanna and husband Adam Horovitz attend "The Punk Singer" screening at Liberty Hall in the Ace Hotel on November 24, 2013 in New York City.

She fell in love with Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz while he was still married.

Hanna recalls a glorious summer that Bikini Kill spent touring around Australia as part of Summersault, a huge traveling festival that also featured acts like Foo Fighters, Beck, and most importantly for her, the Beastie Boys.

She grew especially close with Beastie rapper Adam Horovitz, who she describes as “the person I thought of from the moment I woke up until the second I fell asleep. He was the center of my every fantasy. Unfortunately, he was also married. I knew his marriage was on the rocks, but because he was ‘taken,’ we never even held hands. I was scared I was the only one who thought we were falling in love.”

When Beastie Boys eventually left Summersault to embark on their own tour in Asia while Bikini Kill remained Down Under, Hanna recalls keeping up her blossoming relationship with Horovitz in extremely ’90s fashion.

“For the rest of our tour, Adam and I faxed letters and drawings back and forth to each other’s hotels every day… By the time I got back to Olympia, I was madly in love with him, and we’d still never even held hands.”

She shares what she really thinks about the Spice Girls co-opting the phrase she coined.

By 1997, British pop phenoms the Spice Girls were everywhere, shouting out their very Riot grrrl-esque catchphrase: “Girl power!”

“One of the Spice Girls said something like ‘Wearing high heels and being sexy is girl power feminism.’ … The Spice Girls were not very nuanced or forward-thinking. Ginger Spice called Margaret Thatcher ‘the first Spice Girl; the pioneer of our ideology.’ Yikes,” Hanna writes of the girl group.

“I also found it annoying that they were making tons of money while I was barely making rent. But knowing that Darlene Love was paid an embarrassingly small fee for singing lead vocals on the iconic hit ‘He’s a Rebel’—for which she didn’t get credit, much less royalties—reassured me that my plight was not that serious.”

Bernie Taupin Tells All: Elton, Lennon, and ‘Candle in the Wind’s’ Real Muse

She battled a mysterious illness for many years before finding out what it was.

Many of the memoir’s later chapters center around Hanna’s battle with a mysterious illness that gave her debilitating pain, insomnia, difficulty speaking, seizures, and other scary symptoms. She was diagnosed with everything from MS to Crohn’s disease, but in September of 2010, after being sick for five years, she finally got the correct diagnosis: Lyme disease.

“I’d evidently had it since I was a child. That was the reason for my high fevers and why I missed almost a year of high school. Because it wasn’t treated, it’d never gone away and had affected my muscles, my blood, and my brain.”

Her health problems had even sped up her decision to marry Horovitz, with whom she tied the knot on Jan. 1, 2006, in a super-low-key ceremony.

“The theme of my wedding was ‘Just another beautiful day,’ because despite being sick a lot, every day I spent with Adam was beautiful in one way or another,” Hanna writes. “...But that wasn’t why we got married. We got married because my health insurance ran out and I needed to get on his. Even though it wasn’t a romantic reason, our wedding was still the best. It was just us, two friends, and a reverend named Suzanne who we found on the internet.”

She defends her relationship with Horovitz against fans who think ill of the Beastie Boys.

“While I was ill, I got sent a YouTube link to a band that wrote a song making fun of my marriage. It was a terrible song by an even worse band about how I used to be a feminist until I married a Beastie Boy and became a total jerk,” Hanna writes. “It hurt my feelings a little, because I was a jerk long before I met Adam, and I hated the dehumanizing idea that marrying him was ‘off brand’ for me.”

“I knew that Adam’s band’s sexist lyrics from the eighties—’Girls do my laundry,’ etc.—were great fodder for people to say I was a bad feminist for marrying him,” she goes on. “But I also knew he’d changed and grown since then. He and his bandmates had addressed their sexism by writing lyrics that reflected their support of women and talked openly about their mistakes in interviews.”

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.