Rising country stars strengthen the genre's unprecedentedly authentic hip-hop ties

Please don't stop me, because you haven't heard this one before.

A blues man, soul crooner, gospel singer and redneck rocker walk into a country bar.

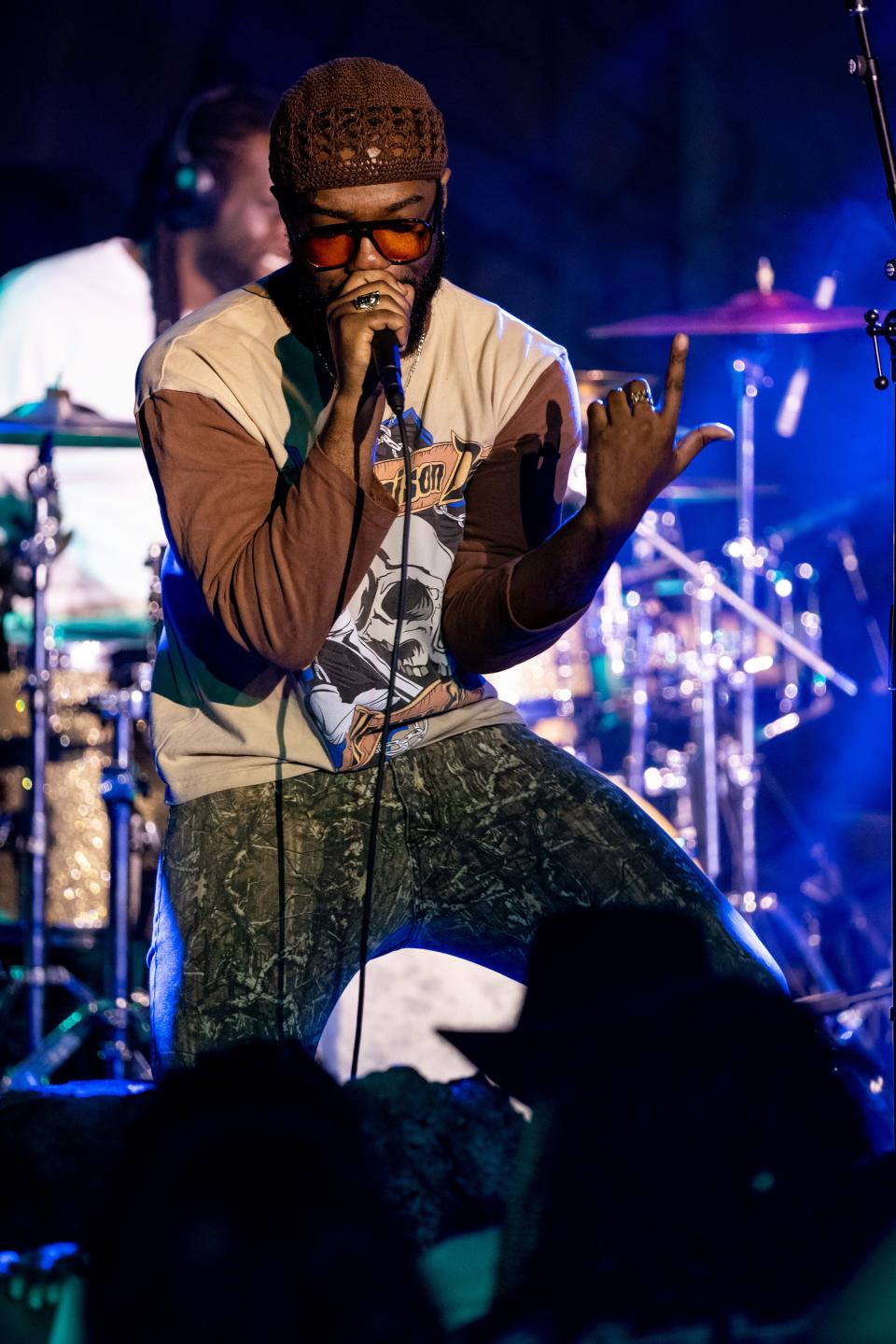

After three hours of performances at downtown Nashville's EXIT/IN on Friday evening, Blanco Brown, Willie Jones, Renee Blair and RVSHVD highlighted that, among many things, that legendary rapper Lil Wayne is peerlessly connected to George Jones, Hank Williams and Johhny Cash as one of the great guitar-driven balladeers in the history of music.

Their charismatic performances also proved something further.

To merely state that country music has a race problem is wrong. Instead, country music's perpetuation of its astonishing cultural blindness -- to the point of fanbase oversaturation and the removal of authentic integrity from the genre's most significantly popular variant -- is worse.

Country music, remember, is a century-old genre whose insistence on a deeply-rooted unbroken circle of history is fundamental to its perpetuity.

For example, country music maintains connectivity to bluegrass music via an eight-decade-old ancestral tie from Bill Monroe to Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs and Ralph Stanley, extending through to Ricky Skaggs, Marty Stuart and Keith Whitley, deeper yet to Dierks Bentley and Billy Strings.

Thus, the idea that country music's tie to authentic, top-tier, pop-ready hip-hop culture starts with Nelly and meanders past Atlanta trap OG T.I. and second-wave pop-crossover New Orleans bounce artist Lil Wayne directly to essentially the gifted and crowd-pleasing cover-band openers for rap DJs at Georgia college bars like Jason Aldean and Luke Bryan feels wildly off.

At EXIT/IN, an event that saw Jones headline, RVSHVD supporting, Blair opening and Brown appearing as a guest performer, did more than any single event in recent memory to rectify a two-decade-old blind spot in how a genre obsessed with ancestry and storytelling authentically tells its most popular stories.

"It's vibes, man. There's something in the water," says Jones to The Tennessean before hitting the stage for an hour-long set.

He's a native of Shreveport, Louisiana. Of course, Shreveport's a major city -- but for the purposes of modern country music, it occupies space directly between Lainey Wilson's hometown of Baskin, Louisiana, Ashley McBryde's roots in Waldron, Arkansas, Charley Crockett's beloved Dallas and Janis Joplin's legendary home in Port Arthur, Texas.

Imagine one artist able to flexibly maneuver through the gumbo of core inspirations driving that artistic quartet.

Jones' latest single, "For My Dawgs," pairs with Brown and RVSHVD.

Alongside his 2021 summer anthem "Down By The Riverside" and 2022's "Slow Cookin'," it continues in his swirling creative evolution.

"The beat, the melody, and the lyrics of the chorus were always a smacker to me," he states via a press release. Brown adds that the record has a "congenial" feeling.

"Our fans lived through a time where -- though it wasn't in the mainstream yet -- everyone listened to Jason Aldean and T.I. at the same time," adds RVSHVD.

"Go into any locker room in America. Trust me; they're listening to a song that sounds like ["For My Dawgs"]."

Athletes in country music include ex-baseball pitchers Brian Kelley and Morgan Wallen and high school football stars Sam Hunt and Cole Swindell.

The lineage is profound but also deserves equity and rectification.

St. Louis native Renee Blair's been in Nashville for 15 years. As much as she's inspired by the musical leanings of her rusted pickup truck-driving and hole-digger father, it's her parents' sacrifice to send her to a wealthy private Catholic grade school as a child during the era where fellow St. Louis resident Nelly achieved nine top-ten Billboard Hot 100 chart singles in under a half-decade proved massively inspirational.

"High school parties were as much about Alan Jackson's "Chattahoochee" as they were about celebrating Lil Wayne's musical catalog," Blair adds.

Evolving country music's female-driven party vibes into a space where Shania Twain and Carrie Underwood's rock-tinged stylings are inclusive of what Blair refers to as her "Hillbetty" movement (featuring her new single "Holy Cowboy") is as significant as it is hilarious and honest.

Blair's creation involves using bluesy guitar licks and hip-hop drum loops to inspire "bachelorette parties of dental hygienists and first-grade teachers from Omaha" to feel perfectly okay with being "bad, dangerous, edgy and wild as hell," -- which may cause the time of their life to involve belching loudly, in an unexpectedly deeper than usual manner, then rushing to vomit in a honky-tonk bathroom -- not that Blair would have first-hand knowledge of that behavior, of course.

Three chords and the truth, indeed.

When asked about perhaps her greatest contribution to the conversation of late, Blair demurs.

She's a credited co-writer -- alongside HARDY and her husband, Jordan Schmidt -- on HARDY and Lainey Wilson's No. 1 country single "wait in the truck."

"I joined the writing process late," she says. "[HARDY and Schmidt] wanted a girl on the 'have mercy on me' chorus. I put so much effort into recalling all of the Aretha Franklin and Whitney Houston gospel influences I could when I stacked the vocals on my part in that song."

Her unique passion has elevated the hit song's impact.

As for RVSHVD, he was born Clint Rashad Johnson in Willacoochee, Georgia.

The town of roughly 1,000 people is an hour from Valdosta State University. Like many towns in the area, it is intriguingly very traditionally rural but also features an almost equal racial split between a population where one in three residents live in poverty.

Johnson and Blair cackle when Blair highlights that many people either don't realize or conveniently forget that the "hot s**t" that Nelly is describing "Country Grammar"'s childhood patty-cake rhyme chorus are the bullets flying from a 12-gauge shotgun he's "cocked ready to let go" while sitting in the passenger seat of a luxury SUV.

"All of my stories are true," says RVSHVD. "Black and white kids have it hard out here. There are as many guys hustling in Ford Crown Victorias as there are in Ford F-150s. It's all the same grind."

Fascinatingly, in a January 2023 Tennessean feature, country star Brantley Gilbert counts time playing in RVSHVD's backyard at Valdosta State alongside gigs at Georgia Southern University, the University of Georgia's various campuses statewide, the Universities of North and West Georgia as providing the grit that has allowed his 15-year Music City career to sustain itself.

About those gigs, another artist familiar with the territory -- 26-time Billboard country chart-topper Luke Bryan -- jokingly adds in a November 2022 Tennessean feature, "Have you ever been in a college bar and heard Nitty Gritty Dirt Band's 'Fishing In The Dark' and then seen Ludacris, Outkast, and Three Six Mafia fill a dance floor?"

Apropos of that history, it makes total sense that RVSHVD's set is highlighted by covers of Brooks and Dunn's "Red Dirt Road" and Johnny Cash's "Folsom Prison Blues" as much as original songs like "Dirt Road" ("a little country and a little street / and it's hot as hell, but we still roll with heat").

Quietly, the pinnacle of Blanco Brown's musical catalog doesn't limit itself to achieving a No. 1 hit country singles with "The Git Up" and Parmalee collaboration "Just The Way."

Within the past 20 years, the proud native of West Atlanta's Bankhead neighborhood has achieved a career as an artist, collaborator, engineer and producer that has intersected with Outkast, the Dungeon Family, Jeezy, 2 Chainz and more.

Thus, he represents the most logical cultural connector between rap music's core Southern roots and country music's history. Because the genre's connective ties between the genres have been fundamentally flawed for so long, his existence in the space is ultra-important.

He cites Goodie Mob's 1995 folksy, funky hit "Cell Therapy," Outkast choosing to include a countrified harmonica breakdown in their 1998 single "Rosa Parks" and Field Mob's bluesy 2002 single "Sick Of Being Lonely" as needing to be revived in conversations about modern country's hip-hop influences being limited to Nelly's 2000-released debut single "Country Grammar."

"If the music makes you want to party, it's a party song -- if the music makes you want to cry, it's a sad song," Blair says.

"We're making experimental music that sounds like nothing that's ever hit the radio before," continues Brown. "The feelings and intentions that drive this music are unprecedented."

When asked the most significant value of nights like Friday evening at the EXIT/IN, Blair offers an irreverent answer, perhaps aware that country music's future is already well into being revolutionized.

"Life's too short to argue about genres."

This article originally appeared on Nashville Tennessean: Rising country stars strengthen the genre's unprecedentedly authentic hip-hop ties