Robert Hunter on Grateful Dead’s Early Days, Wild Tours, ‘Sacred’ Songs

Fifty years ago this May, Robert Hunter popped into a pizza parlor in Menlo Park, California, to see his friend Jerry Garcia play in his new electric band, the Warlocks. “They were good, just dandy,” recalls Hunter, sitting in the living room of his San Rafael, California, home. “It was hard to believe Jerry in a rock & roll band, I’ve got to say. He was a folk musician. But then to become a rock & roll band, him and Bill and Weir and Pigpen—it was amusing. It just seemed unlikely, and it was also a time of odd band names.”

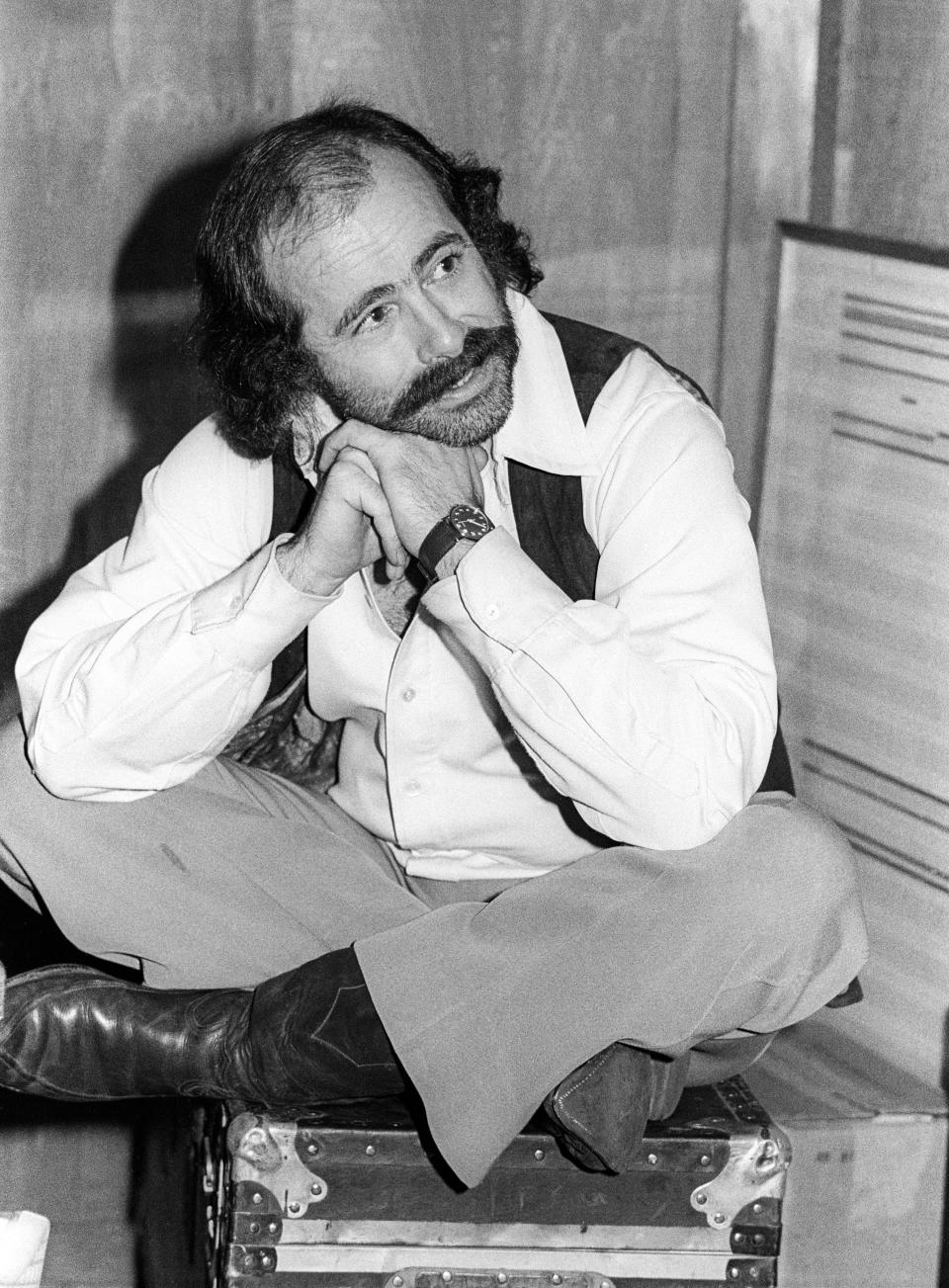

This July, the “core four” of the band that the Warlocks became, the Grateful Dead — Bob Weir, Phil Lesh, Bill Kreutzmann and Mickey Hart — will reunite for shows in Chicago to commemorate the Dead’s 50th anniversary, joined by Phish singer-guitarist Trey Anastasio. But if there were a core fifth surviving member, it would be Hunter, the Dead’s longtime primary lyricist. Garcia’s guitar, Lesh’s massive bass, and the dual Kreutzmann-Hart drums defined the sound of the Dead. But Hunter’s words — heard in “Uncle John’s Band,” “Ripple,” “Eyes of the World,” “Dire Wolf,” “Standing on the Moon,” “Touch of Grey,” “Dark Star,” “Box of Rain,” and so many other milestones in the Dead’s catalog — were the band’s poetic, story-telling soul, often matching the untamed, exploratory nature of the Dead themselves. “You’d see Hunter standing over in the corner,” recalls Hart of the time Hunter joined up with them. “He had this little dance he’d do. He had one foot off the ground and he’d be writing in his notebooks. He was communing with the music. And all of a sudden, we had songs.”

More from Rolling Stone

The songs Hunter wrote with Garcia (and, occasionally, Lesh and Weir) have lived on, covered by Willie Nelson, Patti Smith, Tom Petty, Los Lobos, Elvis Costello, even Sublime. “Hunter tapped into his generation the same way Dylan did,” says Mike Campbell of the Heartbreakers, a longtime Dead fan. “People will look back and say, ‘That’s American culture represented in music.’ He captured the hippie freedom, the mentality of the little guy against the corporation. A lot of the songs are about gambling, card playing and riverboat guys who’ll cut your throat if you look the wrong way.” Perry Farrell, who covered “Ripple” with Jane’s Addiction, calls Hunter “a poet on the level of Kierkegaard,” and Scott Devendorf of the National says, “Hunter’s lyrics say the right things in a few words, like ‘dry your eyes on the wind.’ His lyrics tell a story, and he can turn a phrase in ways that aren’t obvious.” In what could seem like final validation, Hunter and Garcia will be inducted in June into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, the respected industry institution whose previous inductees range from Stephen Foster, Irving Berlin, and Woody Guthrie to John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and Bob Dylan.

For Hunter, the work has continued since Garcia’s death. He’s written songs with Costello, Bruce Hornsby, roots country savior Jim Lauderdale, and his former Dead band mates for their post-Garcia projects. Hunter is even one of the very rare lyricists Dylan has turned to for collaboration: The two co-wrote most of the songs on Dylan’s 2009 album Together Through Life. “He’s got a way with words and I do too,” Dylan told Rolling Stone at the time. “We both write a different type of song than what passes today for songwriting.”

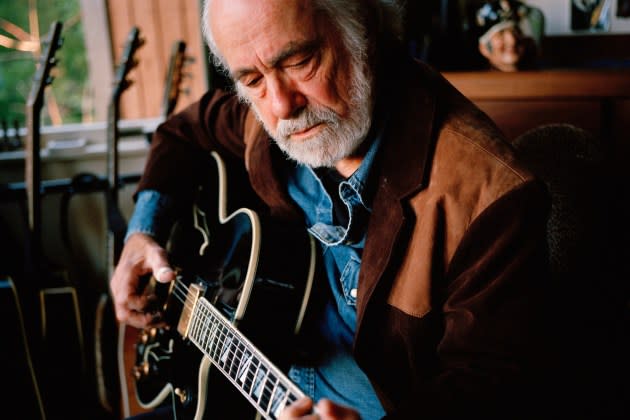

By his own admission, Hunter has long been an irascible character even in the world of the Dead, rarely doing interviews and maintaining a low public profile. “I was basically a maverick and a rebel’s rebel even amongst the Dead,” he says. “That’s how I grew up. Always the new kid in school. Everybody wants to challenge you all the time.” But three years ago, he came close to dying thanks to a spinal abscess and the discovery of bladder cancer. After recuperating, Hunter hit the road for short tours in 2013 and 2014, an experience that revitalized him and reconnected him with adoring Deadheads. Playing solo acoustic, his guitar approximating Garcia’s chords and his voice often revving up to booming sea-shanty power, Hunter was received rapturously by fans who hadn’t seen him onstage in roughly 10 years. “I didn’t expect that good of a welcome,” Hunter says now, “and it was a lot more fun than I would’ve thought.”

With that, Hunter, 73, feels the time has come to talk about the band that delighted, inspired and vexed over three decades. Over the course of two interview sessions at his home, Hunter, dressed in a denim shirt and slacks, settled into a plush chair in his living room and gave RS a rare peak into his work, life and relationship with Garcia and the Dead. In part one, he covers the Dead’s rise, sharing stories about the band’s chance formation, beloved tunes and wild tours; you can read part two here.

“I’m being pretty darn frank in this interview, aren’t I?” he says at one point with a grin. “The great ‘me’ pontificates on what the great band should have been doing according to my brilliant lights! You can quote that!”

Let’s start at the beginning: Legend has it that you met Garcia in Palo Alto on 1961 at a local production of Damn Yankees.

He was 18 and I was 19, and we had somewhat similar experiences in a certain sort of way—he lost his father to death and I lost my father to a divorce. Before I moved off to Connecticut in the 12th grade, I was dating Diane Huntsburger. She was doing lights for the show, and Jerry was her boyfriend and he was there that night. She remained a good friend, so she said to go to Damn Yankees and introduced me to Jerry and I say, “Hey, how’s it going.” He didn’t seem very enthusiastic–as if all he wanted was to meet some of his girlfriend’s old boyfriends [laughs].

But the next time I met him was at St. Michael’s Alley, a coffeehouse, just a couple nights later, I think. I went in to see if there was any kind of crowd to hang out with. I didn’t really know anybody in town at this point. [Garcia and his friends] said, “Hey, you got a car?” And I said, “Uh, yeah,” and they said, “Would you like to go see Animal Farm tomorrow? It’s supposed to be in Berkeley or something,” and I said yeah, sure. The next day they’re banging on my door, him and Alan Trist. We didn’t see Animal Farm, but somehow we managed to drive in my old car, which I got for $50, a 1940 Chrysler. I didn’t know what we did do! We might have had enough gas to get there. We were all broke!

How did you complement each other from the beginning when you met?

A couple of nights after I met Jerry, we went over to this party. There was one guitar there and I start playing it, which is what I usually would do, and Jerry asked if he could have the guitar. And never gave it back [laughs] We got another guitar somehow or another to do the gigs with. We had guitar and folk music in common. I’d been in the folk music club at the University of Connecticut, so I had my folk music and guitar playing, and Jerry, same, same, so we hit it off. To me, Jerry just had a really interesting mind, you know; he was just phenomenal, fun to talk to. All day long, he’d just sit there with this action [picks up guitar and plays fingerpicking folk figure]. He never stopped playing guitar.

What was the first song you wrote — was it “Black Cat”?

That’s right! I’ll sing it to you. [Grabs his guitar] I don’t think it’s ever been sung: “Tell you a story about my old man’s cat/Cat whose hide was uncommonly black…” [Sings entire song with a huge grin] Jerry and I didn’t have anything else to do and we just wrote the song, and neither of us ever thought about it again. Our first group was Bob and Jerry, and our first gig was at Stanford. We got $5 for both of us. We kept it for a couple of days until we needed cigarettes, and then that was that.

You also played in early bluegrass groups with Jerry.

[Nods] And then I didn’t get into the Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions [the pre-Dead jug band], although I was offered. Jerry came over and said, “Would you like to play jug in the band?” But I couldn’t get a tone out of it. I suppose if I had accepted that jug, I would’ve changed the whole trajectory. That wasn’t my direction of travel. I think writing for the Dead was the best thing I could’ve done. In fact I remember at a certain point thinking, “What was I thinking about being a novelist? This is where it’s at.”

And legend has it you were the first in the gang to try LSD, thanks to a testing program at a VA hospital.

I used to do psychology experiments — you could get $10 or $15 for doing them, and this was one of them, only this paid better. I had a romping good time. They wanted to find out was whether it increased my ability to be hypnotized. Just a couple of years back I found out it was military or the CIA or something, that they were trying to find its value as a weapon. For me they would’ve found out absolutely nothing. I told Jerry, but there was no way to get ahold of any of this stuff; it wasn’t on the streets yet or anything. It wasn’t until I’d say a good two years later when Jerry took it and he and Sarah [Ruppenthal, Garcia’s first wife] came over to my house. They were on acid and said, “What do we do now?” I said, “Go home, put on a Ravi Shankar record, just listen to the music.” It worked. That was good advice, no?

At one point in the mid ’60s, you also reportedly looked into a new organization called Scientology.

For a short time. This was a brand new thing at the time. This fellow came down and was telling us fantastic things, like you get could get out of your body. All of that sounded great. But let’s just say Scientology and I were not a very good match. I was pretty independent minded. Jerry came to one of the meetings. And he truly didn’t care for it. We did these confronting drills and stared into each other’s eyes for long periods of time and tried not to think without trying and not blink. [Chuckles] I gave it the good old college try but then moved into other forms of spiritual endeavors and yoga. I was a seeker at the time and this was one of the places I sought and it wasn’t a good fit. In the end the Grateful Dead fit. I thought there was a possible holy perspective to the Grateful Dead, that what we were doing was almost sacred.

What do you mean by sacred?

The spirit of the times. It was happening in the Ashbury district at the time, although it didn’t last very long before everybody just descended on Haight Street. But there was a time I felt this was the way the world would be going in a spiritual way, and we were an important part of that. I didn’t feel we were a pop music band. I wanted to write a whole different sort of music. Jerry and I had differences on that. He would say, “Goddamn it, man, we’re a dance band! Stop doing stuff like ‘Eagle Mall’!” He was right: the Dead were a psychedelic dance band. Jerry had written “boogie” on his pedal steel guitar, so he wouldn’t forget to boogie.

Were you there during that famous night in 1965 at Phil’s when they found the name “Grateful Dead”?

No, no! I would’ve talked ’em out of it. Definitely. It was outrageous is what it was, one of those things when you’re sittin’ around stoned that sounds like an incredibly good idea. However, time has its way with things, and now it seems like one of the finest choices possible.

Let’s talk about how you became the Dead’s primary lyricist in 1967.

I got pretty deeply into speed and meth and came close to messin’ myself up. The scene I was in, I had to get out of that scene entirely, because as long as it was around I would be tempted, so I went off to New Mexico. And while I was there I had been writing some songs, mostly before I left Palo Alto. I had written “St. Stephen” and “China Cat Sunflower,” and I sent those — and “Alligator” — off to Jerry, and he uncharacteristically wrote back [laughs]. He said they were going to use the songs and why didn’t I come out and be their lyricist? Which I did.

And there’s the famous story of you listening to the band rehearse and coming up with some of “Dark Star” as they played.

Right, because they were rehearsing it right away. They were playing and I wrote down a verse for it and it worked. Then a couple of weeks later, I was sitting in the Panhandle [in San Francisco] and writing out a second verse, and this guy came up and said, “Hey, you want a hit?” I don’t remember if I took it or not, but I said, “I’m writing the second verse for the song called ‘Dark Star’ for the Grateful Dead — remember that.” I had a prescience about the whole thing at that point. Once I started believing in that band, I thought, we’re going to go the distance.

Did you often write when you were high?

Sometimes you got high and sometimes you didn’t. Sometimes you took speed and sometimes you smoked pot. I actually wrote one song drunk, “Dupree’s Diamond Blues.” [Chuckles] And God knows how I wrote “China Cat Sunflower.” I was working on that for months, adding verses and drafting this, that and the other thing. I find that writing on pot, I throw an amazing amount of stuff away that looked groovy to me while I’m stoned and doesn’t look groovy afterwards. If I want to be productive it’s best to be straight. Now, a cup of coffee is going to get me going, and that’s about it.

How would you write songs with Garcia?

Jerry didn’t like sitting down by himself and writing songs. He said, “I would rather toss cards in a hat than write songs,” and this was very true. There were situations where he would come over and have melodies and we’d see what we could get out of that. More often I would give him a stack of songs and he’d say, “Oh, God, Hunter! Not again!” He’d throw away what he didn’t like. I’d like to have some of the stuff he tossed out! I don’t know where it went. I wrote once about “cue balls made of Styrofoam” — that line from “Mississippi Half-Step Uptown Toodeloo.” Jerry took objection to the word Styrofoam. He said, “This is so uncharacteristic of your work, to put something as time dated” — or whatever that word would be — “as Styrofoam into it.” I’ve never sung that song without regretting I put that line in. Jerry also didn’t like songs that had political themes to them, and in retrospect I think this was wise, because a lot of the stuff with political themes from those days sounds pretty callow these days.

What would surprise us to learn about you and Jerry hanging out in the old days?

Jerry and I used to watch Porter Wagoner’s show. Then afterwards we’d watch Sesame Street, which had just come on. It was mind-boggling. There was nothing ever like that on television before.

What do you recall of that legendary 40-minute instrumental tape the Dead gave you that became “Uncle John’s Band”?

Oh, it wasn’t that long. But yeah, it was the music for it, and I had it on tape and played it over and over. I think I started out with “Goddamn, Uncle John’s mad,” and like that, which turned into “Uncle John’s band.” But it was my feeling about what the Dead was and could be. It was very much a song for us and about us, in the most hopeful sense.

How about “Ripple”?

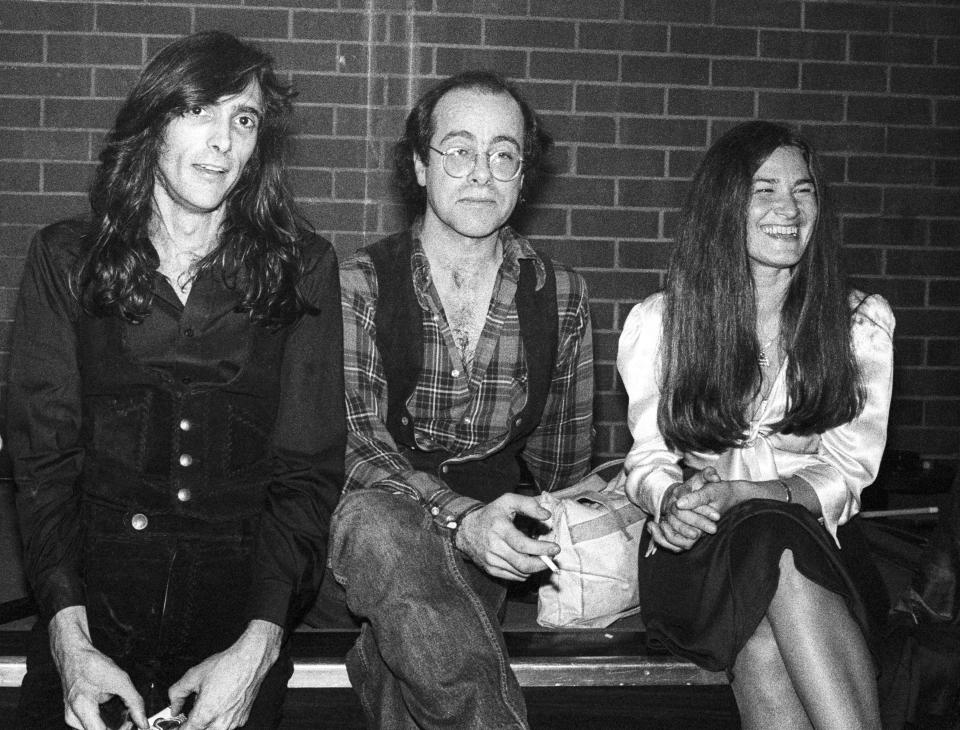

We were in Canada on that train trip [the Festival Express, 1970] and one morning the train stopped and Jerry was sitting out on the tracks not too far off, in the sunrise, setting “Ripple” to music. That’s a good memory. That was one of the happy times, going on that train trip. Janis [Joplin] was the queen of that trip. One of my greatest memories is having breakfast with her on the train. She was having Southern Comfort and scotch, and she asked me if I heard that song by Kristofferson, “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down,” and she sang it in my ear. Can you imagine?

“Truckin'” also was completed on the road with the Dead, wasn’t it?

Yeah, I think it was in Florida, and I had been writing it for some time. I think I finished it there — it was not a song I just dashed off. And then I gave it to them. They were all sitting around the swimming pool, the guitars there, and they did a good job on it. I wrote all the lyric. “Sometimes the light’s all shinin’ on me” — I think that’s Phil. It took me a couple of months to write and it maybe took ’em about half an hour to put it together.

Did you know Phil’s dad was seriously ill when you wrote the lyrics for “Box of Rain”?

Yeah, a song for Phil’s dad. It wasn’t about dying in particular; it’s about being alive. I wrote “Playing in the Band” to the sound of the pump on Mickey’s ranch. We put chords on that rhythm. The rhythm was provided by nature. “Fire on the Mountain” was right around the same time, also at Mickey’s ranch. There was a fire on the mountain and it looked like it was going to endanger the ranch. So what did I do about it? I sat there and wrote a song about it while the smoke was pouring out. A good starting point.

When it comes to working with the band, do you have a favorite era?

Well, I think the most fun was down in L.A. doing Anthem of the Sun, which was way back in the beginning for me — just hangin’ around being great friends and all that kind of stuff. Weir’s famous quote to the producer, Dave Hassinger, at that time: “We’re looking for the sound of thick air!” [Laughs] I was there when that was said.

How about a favorite lyric or line you wrote?

“Let it be known there is a fountain that was not made by the hands of men” [from “Ripple”]. That’s pretty much my favorite line I ever wrote, that’s ever popped into my head. And I believe it, you know?

To prepare for your recent tours, you’ve said you listened back to Dead albums again. What was that like for you?

Some of the versions sound better almost than I can believe, and Jerry’s guitar playing and his knowledge of the modes and stuff is overwhelming. And sometimes, somebody in the band is just singing flat [laughs]! Which, as a lyricist, tends to ruin a song for me. Sometimes it’s phenomenal, though. “Casey Jones” didn’t start out as a song, it just suddenly popped into my mind: “driving that train, high on cocaine, Casey Jones, you better watch your speed.” I just wrote that down and I went on to whatever else I was doing, and some time later I came across it and thought, “That’s the germ of a pretty good song.” The remixes on some of those albums sound so brilliant you can’t believe it, you know. They sound like what they should’ve sounded like back then.

Best of Rolling Stone