‘Robot Dreams’ Review: Pablo Berger’s Lovely But Opaque Animated Buddy Movie

Effectively a dialogue-free oddity like his black-and-white breakthrough Blancanieves, comic-sad fable Robot Dreams, an adaptation of a graphic novel by Sara Varon, represents Spanish director Pablo Berger’s first foray into 2D animation.

Set in a recognizably scruffy cartoon version of 1980s New York, the main characters are a lonely dog and a robot he builds for companionship, living lives of quiet desperation among a teeming metropolitan menagerie of bipedal animals. (Think old Looney Tunes shorts, or BoJack Horseman but without any fully human characters or zingers.) Acquired by Neon just before its premiere in Cannes, this often charming but patchy and sometimes slightly confusing work is likely to find a niche audience in New York itself and perhaps beyond. But its wistful, melancholy tone won’t make it easy to market, especially as it doesn’t feel like it’s for either young children or for the slightly older crowd who are into racier, more potty-mouthed cartoonery like BoJack, Rick and Morty and the like.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

All the same, it’s hard not to get a little warm and fuzzy over a movie that features not one but two joyous rollerskating or dance sequences set to Earth, Wind & Fire’s dancefloor-filling classic “September,” and a moody jazz interpretation as well that plays elsewhere in the film. Indeed, the use of music and sound design is very thoughtful throughout, capturing the way music by street performers makes life in the city feel like a musical all the time while the murmur of traffic and general hubbub creates its own atonal backing track. Although the graphic style is very much in the “clear line” tradition of old school comic books, the backgrounds brim with little in jokes and well observed details that evoke Manhattan’s Lower East Side when it was still grungy, full of graffiti, trash and a sense of danger.

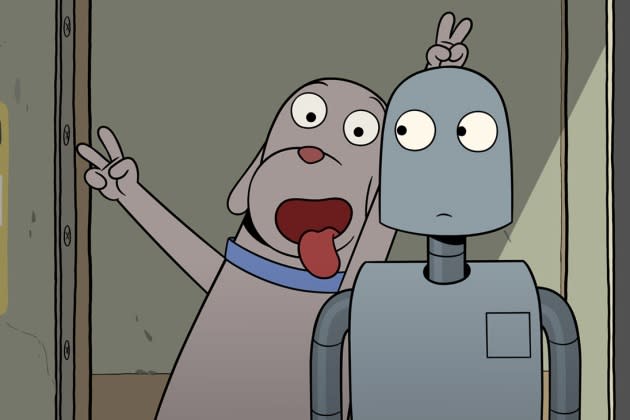

In a small studio apartment on E. 13th Street, Dog Varon lives alone, watching TV and living off microwaved macaroni meals. It’s not clear what the poor mutt does for a living, but he can somehow afford to buy a build-it-yourself robot that comes in a kit. As he’s watched by a gaggle of curious pigeons on his window sill (the iridescence of their feathers is pleasingly represented by just a couple of straight lines of color around their necks), Dog assembles Robot, an AI-driven bot who doesn’t chat but likes going for walks with Dog.

They take in the sights of the city together, which includes eating sidewalk hot dogs and Central Park, where they first rollerskate to “September,” their theme song for the rest of the movie. Some viewers may feel a little confused by what their handholding means (Robot squeezes too tight at first but soon learns): Are they sweethearts or just buddies? Who knows, but maybe it doesn’t need a name.

Anyhoo, one day in, presumably, late September or a month that doesn’t have an EW&F song about it, Dog and Robot ride the subway all the way out to the beach and have fun perambulating the boardwalk and splashing in the waves. But when they fall asleep on the sand and wake up after sunset, Robot’s joints have rusted over and he can’t move. Dog tries his best to help but isn’t strong enough to move his friend’s metal bulk. With Robot’s encouragement, he goes back to Manhattan to sleep and collects tools to help Robot, only to find that the boardwalk and beach are now closed until June and he can’t get in no matter how hard he tries.

It’s at this point that the film effectively splits into two separate narratives, with Dog going on with his life as before with just a note on his fridge to remind him to pick up Robot when the beach opens in June. Stuck in the sand, Robot starts having dreams or fantasies of escaping and reuniting with his dear friend Dog, hence the title, but he always wakes up and feels the pain when he realizes nothing has changed. A bird builds a nest next to him and he feels deep love for the chicks, but over the winter the sand just grows higher up around him.

Thankfully, the narrative trajectory doesn’t land in full-on tragedy, despite the early signs seeming to point that way. But it’s not a happy ending either. Given that the relationship between the two main characters is so sketchily defined, what Berger is trying to say with the conclusion is quite opaque. Are we to read this as an allegory of lost love or just the pang you get when you’ve lost touch with someone and now it’s too late to make up again?

Whatever the case, there’s definitely feeling there that speaks without words, and perhaps every viewer is free to interpret whichever way feels right. There’s eight million stories in this naked city.

Best of The Hollywood Reporter

Solve the daily Crossword