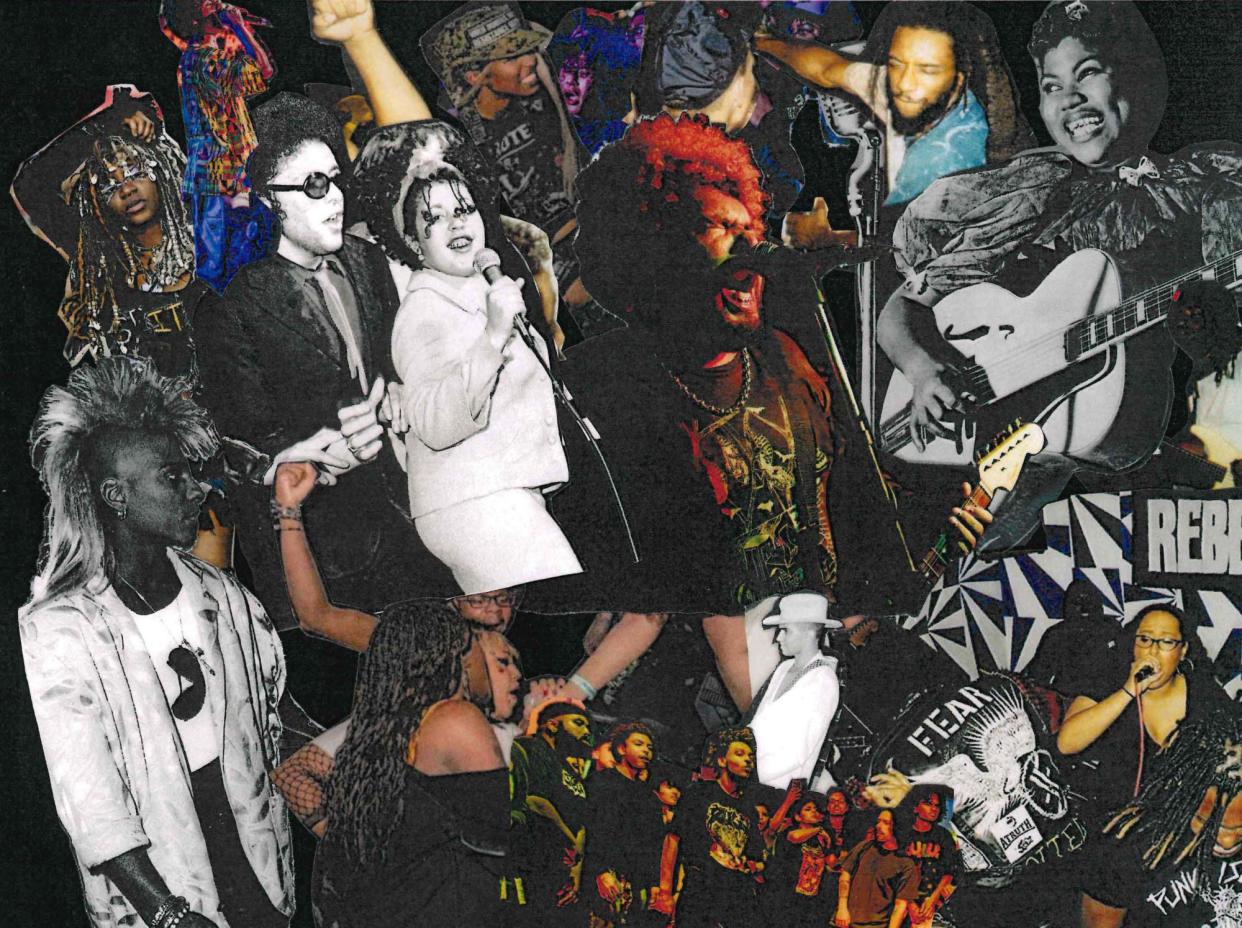

The rockers putting their Blackness at the fore of hardcore and punk

Pierce Jordan’s guttural scream filled the halls of Philadelphia’s First Unitarian Church one night last October. He was surrounded on stage by other Black hardcore musicians plucking guitars, flailing their arms to the beat of the drums and diving into the crowd below. The air was heavy with body heat as attendees broke into a mosh pit and slammed into one another.

As the frontman of the hardcore band Soul Glo, Jordan is part of a growing movement of rockers who are bringing Black culture and aesthetics to the forefront of a scene that has long centered whiteness. The band occasionally raps over heavy guitar riffing, “because we like rap music, but it’s also because it’s part of [Black] tradition”, Jordan said.

Related: Black artistry is woven into the fabric of country music. It belongs to everyone | Rhiannon Giddens

At a Nepali restaurant in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he wore a pink sweater, a chunky gold necklace and gold grills over his teeth. “I’ve never seen anybody who’s Black in a punk band with gold teeth,” Jordan said. (While definitions vary, hardcore is a music genre and subculture that is usually slower than punk with more breaks where the tempo slows down. Some other features include do-it-yourself ethics, characterized by self-sufficiency and a rejection of mainstream culture.)

Soul Glo also nods to Black culture in the cover art of its most recent album, Diaspora Problems, which Rolling Stone named metal album of 2022. The black-and-white photo of an altar features an Afro pick, along with a copy of the late writer Audre Lorde’s book I Am Your Sister. Jordan said Lorde, whose writing tackles themes of Black feminist thought, has influenced his creativity. That cross-cultural pollination is common among Black hardcore musicians today, many of whom said they incorporate Black art from other genres and mediums into their work.

Even though hardcore was pioneered in the 1970s in part by Black musicians such as Bad Brains, the genre has mostly been dominated by white bands. But a new era of rockers has emerged in the past decade, and the Black hardcore scene has gained traction through festivals such as the Break Free Fest in Philadelphia and the recent releases of the books The Secret History of Black Punk: Record Zero, an illustrated archive of overlooked luminaries, and Black Punk Now, an anthology of nonfiction, illustrations and comics around Black punks. Longtime musicians are mentoring the younger generation and educating them on the Black roots of the genre. And perhaps now more than ever before, artists are using their style and lyrics to highlight their Blackness in hardcore.

“I’ve been calling it the Black punk renaissance for about a decade now,” said Flora Lucini, vocalist of the Afro-progressive hardcore band Maafa. On 23 March, Lucini will host the first Black Punk Now Fest, featuring her band and others from the African diaspora, in Brooklyn, New York. “My generation [millennial] and younger have injected this new breath of life into hardcore and punk.”

‘You’re standing in a home my ancestors built’

The origins of Black hardcore are tied to spirituality, a recalling of ancestral roots and freedom of expression.

In The Secret History of Black Punk: Record Zero, the author and illustrator Raeghan Buchanan attributes the beginning of rock-and-roll music to the Black musician Sister Rosetta Tharpe in the mid-20th century. With a background in gospel music, Tharpe mixed the call and response found in church services with her unique style of plucking the electric guitar. She recorded what many historians consider the first rock song, Strange Things Happening Every Day, in 1944.

The book highlights other Black pioneers of punk such as the bands Death, Pure Hell and ESG, as well as Poly Styrene of the British band X-Ray Spex and Pat Smear of the Germs. Buchanan wrote that many of these musicians faced racism in a white male-dominated music industry that wanted them to conform to what they considered traditional Black genres, such as rap or funk.

But hardcore and punk are also reflections of Black American musical traditions. “How can I be a guest in your house when you’re standing in a home my ancestors built?” Lucini said, referring to the predominantly white hardcore scene.

The traditional hardcore breakdown, where the tempo slows into a simple rhythm, for instance, is influenced by hip-hop. Punk’s music patterns derive from gospel music. And circle pits, a form of hardcore dancing where people mosh in a circular formation, is similar to traditional African dance styles. The five-note pentatonic musical scale, which is commonly used in hardcore music, she added, originates from the Mali empire, which existed from the 13th to 17th centuries in west Africa.

“Every iteration of hardcore has been propelled forward by the innovations, creations and ideas of Black music and culture,” said Lucini. The style and aesthetics known to hardcore and punk music also can be traced back to Black influences. For instance, the gauged ears seen on many hardcore show attendees have been practiced in Africa for thousands of years.

Lucini, who’s based in Brooklyn, formed Maafa “to embrace the Blackness behind that music” by incorporating instruments such as the djembe and conga along with a different African rhythm in each song.

Growing up as a Black queer teen in Washington DC, Lucini looked to hardcore music to help process the discrimination she experienced from the outside world and the respectability politics from within her community that told her to talk and dress a certain way.

For Black youth in the scene, “hardcore was about working out your frustration of living in housing projects, being harassed by police, watching your friends die of overdose … and feeling like you’re not going anywhere because you have racist white teachers in all-Black underserved schools,” said Lucini. “Hardcore gave us a space to aggressively work out emotions that white punk wasn’t allowing us to do.” Today, she educates young Black female musicians on how to navigate the business side of the industry, such as the ins-and-outs of copyright and publishing rights, and she informs them of Black contributions to the genre.

In the 2003 documentary Afro-Punk by director and novelist James Spooner, which featured Black punks throughout the nation, Brooklyn-based musician Tamar-kali said that her choices about her appearance are her “relating to traditionally African aesthetic, but it was through punk originally that I had those senses reawakened”.

Spooner said that today, he’s “seeing bands that are putting their Blackness on the forefront”. When he first started going to hardcore shows in the 1990s, he said that musicians discussed animal and women’s rights, but never broached the topic of racism. He attributed a change in the past decade to the rise of Black-led festivals, beginning with Afro-Punk, which he co-founded in 2005. “Going to those shows, you’re entering a Black space, so if you are not Black … you have to meet them where they are,” he said.

Paving the way for a new generation

The Black musicians reclaiming the genre with their own shows and festivals hope it will pave the way for a new generation of rockers who feel at home in the hardcore scene.

Scout Cartagena, the 30-year-old founder of Philadelphia’s Break Free Fest, created the hardcore and punk festival centered on Black people and people of color in 2017 to highlight underrepresented musicians.

At the annual festivals, speakers discuss issues relevant to the local community, such as ending cash bail. One year, Mike Africa Jr from the Philadelphia-based communal organization Move discussed his family’s fight for Black liberation and the 1985 police bombing of the movement’s house where 11 people were killed.

Related: A century on from Rhapsody in Blue, debates about cultural ‘theft’ rage still | Kenan Malik

Cartagena makes the festival accessible for Black and other historically marginalized communities by offering free entry to those who can’t afford it. During the festival’s first year, she helped teach Black children to circle pit while they watched the all-Black band Minority Threat.

“We are a family when you come to Break Free Fest,” Cartagena said.

Craving a sense of belonging in the hardcore scene, many rockers have incorporated into their lyrics and aesthetics the theme of Black liberation, which Zulu frontman Anaiah Rasheed Muhammad defined as “pure freedom … for all Africans and Black people around the world”. The cover art of the Los Angeles-based band’s latest album, A New Tomorrow, by the artist Savannah Imani Wade serves as a memorial for abducted west Africans who died during the Middle Passage, with people in kente cloth dancing under a tree.

“I make it a point to show people that they can embrace that side of their [Black African] lineage and still be considered hardcore,” Muhammad said. Zulu’s song Music to Driveby seamlessly blends growling vocals with a sampling from the soul musician Curtis Mayfield.

But the recent rise of the Black hardcore scene has been met with backlash, including online harassment and Black musicians being removed from show lineups, said Lucini. When Zulu printed T-shirts that read Abolish White Hardcore to draw attention to the white-dominated space, hardcore fans accused them of being racist.

Muhammad, 27, is unfazed by the accusations. “There’s no such thing as reverse racism,” he said. “Anyone that said it was racist does not know what racism really is.”

Jordan from Soul Glo sees the backlash in the gatekeeping of hardcore music, where promoters use coded language to define who fits into the genre. “It has had a massive impact on [diversity] because it makes people feel like they can’t exist as their full selves without being judged,” Jordan said.

He hopes that hardcore musicians of the future will acknowledge the contributions of Black music and culture to the genre. For his part, he shares the stage with musicians outside the genre, such as hip-hop duo Armand Hammer.

“That’s how we’ll be free – if we know our history, we know our traditions and we find security in ourselves from that,” Jordan said. “And we can learn that from Audre Lorde.”

default