How Rosalía Became Pop’s Most Fearless Superstar

IT’S HOURS AFTER A SUDDEN RAINSTORM one afternoon in September, and Rosalía is standing with her eyes trained on the placid shore of Puerto Rico’s Bahia Beach. She’s still for just a few seconds, but her mind is stuck on the pure chaos of the previous night.

“Dios mio, it was crazy,” she says, with an edge of gleeful disbelief.

More from Rolling Stone

El valiente trayecto de Rosalía hasta alcanzar el cielo del pop

Kanye West Used Porn, Bullying, 'Mind Games' to Control Staff

First off, let’s not call it a concert. For almost two hours straight, she played for a sold-out crowd at the historic Coliseo de Puerto Rico José Miguel Agrelot. Aside from waves of screaming fans, the spectacle Rosalía put on is more akin to performance art than a traditional stadium show, and it’s taken over cities and social media pages with equal force over the past few months. There’s no opener, no costume changes. Rosalía is at the center, her face often slicked with sweat and tears, doing everything all at once — strumming a jet-black guitar, smacking her gum, pounding an ornate piano, ripping her heart wide open. And as her Motomami World Tour has crossed the globe, this has been her life for the past year.

Her show in Puerto Rico was an all-out rager. Assigned seats were meaningless as security guards roamed the floor, trying — and failing — to stop people from spilling into the aisles. The arena seemed like it was going to collapse in on itself when Rosalía shouted to the crowd, “The love of my life is here!” referring to her boyfriend, the Puerto Rican star Rauw Alejandro. After it was all over, she still found the energy to hit an afterparty at a San Juan nightclub with him. A tangle of iPhone cameras captured them dancing to different hits, including Rosalía’s own “Despechá,” late into the night.

Even so, the next morning, when I arrive at her private oceanfront villa in the St. Regis, where a few of her friends are milling around, she’s bright and alert, wearing a navy-blue minidress with a youthful Peter Pan collar. I have a million things I want to ask, yet it’s Rosalía who immediately starts peppering me with questions before I get the chance.

“OK,” she says eagerly, her eyes lighting up with genuine curiosity. “Tell me everything. How did you feel about last night? This was your first time seeing a show, yes? What did you think? I want to know.”

I quickly fill her in, telling her the only other performance of hers I’ve seen was at Austin City Limits, in 2019. Back then, Rosalía was coming off the breakthrough success of El Mal Querer, the intricate concept album she released in 2018. Suddenly, a promising young graduate of Barcelona’s Catalonia College of Music, who’d dedicated most of her life to the punishing art of flamenco, morphed into a boundary-pulverizing avant-fusionist, one known for her encyclopedic range of cultural references, who interpolated Justin Timberlake, exploded into cante jondo, and cited an Occitan novel about a toxic relationship all on the same project (the text — called The Story of Flamenca — actually inspired the entire album, which was her college thesis).

But if listeners were anticipating more baroque flamenco theater after El Mal Querer, Rosalía swerved, leaping into collaborations with reggaeton and hip-hop artists like J Balvin, Travis Scott, and Ozuna over the next couple of years. Some were mesmerized by her chameleonic abilities, seeing her wide-ranging trajectory as a brave and prophetic vision of a world without boundaries. To others, her approach was an unabashed form of appropriation that highlighted her privilege. She was also weird and playful and hard to pin down: Here you had a disciplined musician, intense about her love of high art and classical influences, but well-versed in the internet and down to bullshit around online, posting bored Insta-baddie selfies, twerking on TikTok, sharing photos of her hangs with the Kardashians, and embracing silly social media trends.

No matter how people felt, they were watching her, fixated on her next move. Sure, she could have cranked out a quick follow-up album that kept her momentum going and expanded her pop potential. But Rosalía, who’s taken creative cues from inspirations like Bj?rk, Kate Bush, and Lauryn Hill, made it clear from the beginning that outside noise wasn’t going to dictate her creative process. “I’d never want to put out records with a sense of urgency, or with the pressure of ‘Oh, it’s been X years,’ ” she says. “I don’t think I’m going to be that type of artist. I think I’m always going to make music when I feel like I have something to say.”

For three years, she worked on an album that was constantly evolving. It started as a kind of protest against any expectations placed on her after El Mal Querer, but it also confronted disorienting changes happening in her personal life: For months, the pandemic kept her an ocean away from her family in Barcelona while she recorded in the U.S. At the same time, she was grappling with fame, having gone from an independent artist with no ties to the industry and no clear path forward to a star facing constant attention and heightened scrutiny. “I didn’t grow up like this,” she tells me. “It’s something new for me in my life, and I think because I’m not used to it, I was kind of like, ‘How do I feel about this?’”

Meanwhile, she fell in love. Since 2020, fans had been linking her and Rauw together, analyzing every social media interaction and scouring their pictures for tiny clues: maybe a parking lot they’d both been photographed in, a fraction of Rauw’s hand in the background of an image. The couple did their best to keep their relationship private, despite mounting speculation and even harassment. (As Rauw told Rolling Stone a year ago, they decided to go public after paparazzi cornered them at a restaurant. “I was like, ‘Yo. What are we gonna do?’ And she told me, ‘You know what? I’m tired of this shit.’”)

Finally, in March, she released Motomami, a collision of styles and genres that packed all of the commotion around her into one ballsy, brilliant statement. The tumult she felt was in the eerie excess of “La Combi Versace,” painting a picture of nouveau riche wealth over a hauntingly sparse dembow arrangement; it was in the discordant combination of jazz and reggaeton in her tribute to legends Daddy Yankee and Wisin on “Saoko,” where she raps about her right to transform and contradict herself.

“It’s a chaotic record,” she says with a laugh. “I wanted the record to feel like an emotional roller coaster, which is what I was feeling at that point in my life. I wanted that dynamic, that constant sensation of toma y daca, give and take.”

Motomami was a genuine pop surprise. David Byrne, perhaps seeing a kindred weirdo in her eclecticism, built an entire playlist inspired by a show she did at New York’s Radio City Music Hall. Lorde covered the positively lewd ballad “Hentai” at a concert in New York. Cardi B — who, along with Megan Thee Stallion, had Rosalía make a cameo in the “WAP” video — raved about the record on Twitter (“soooo fireeee,” she told her 22 million followers). Bigger industry praise came more recently: Motomami earned two Grammy nominations and won Album of the Year at the Latin Grammys in November, crystallizing Rosalía’s place as the heady queen of global pop and an uninhibited provocateur, pulling from kitsch camp to sacrosanct traditions without fear of consequence.

“She’s like water,” says Noah Goldstein, the Grammy Award-winning producer and engineer who worked with her on Motomami. “That’s what you want in an artist — for them to be as adaptable as possible, to bend without breaking, and move fluidly. She’s super hands-on, and that fluidity translates to the way she produces.”

I feel like on ‘Motomami,’ I did and said exactly what I wanted to say and do, on my own terms. After this, there’s no turning back.

Even on a beach in Puerto Rico, the gears in Rosalía’s mind are always furiously turning, transcending. In one conversation, she flips between English and Spanish, sometimes grasping for a word in her native Catalan. She references funny TikTok dances before mentioning the musings of a 17th-century French poet and philosopher, trying to get my help in remembering his name (which I would never know).

She’s been living light-years ahead of everyone else, her mind full of concepts she wants to try and goals she wants to achieve and destinations she wants to reach. Right now, there’s one place she wants to go: “Should we see the beach?” she asks, having just realized the villa has private access. Within a few seconds, she takes the lead, and soon the Atlantic washes over her black Balenciaga crocs. Despite everything bouncing around in her head, she genuinely feels grounded right now, even with the next show, the next city, the next big idea looming. “I feel really anchored, more than any other time in my life,” she says. “I’m really trying to just enjoy what’s happening in every moment.”

ROSALíA THROWS HERSELF INTO THE MOMENT every time she’s onstage. The setup of her Motomami show is minimal, with most of the choreography taking place in front of a stark white backdrop. An onstage cameraman, a network of iPhones strategically placed around the stage, and even some of the dancers film different angles of the action, which are projected onto gigantic screens on either side of the stage. Cameras close in as Rosalía wipes off her makeup at one point; later they capture her as she cuts off a lock of her hair and throws it to the audience, literally giving a piece of herself. The result is visceral and uncanny, like realizing you’re in a film with her rather than watching one.

Toward the end of the show, she’s lying on her stomach, inching her way to the edge of the stage, the iPhones so eerily close that you can see the sweat dripping from her pores. “By that point in the show, I’m so messed up,” she says, laughing. It’s a declaration to the audience — an act of protest against the idea that female artists must present themselves in a specific way. The removal of her makeup, the lock of hair — they’re meant to jar people, remind them that beyond just a performance, this is something real. “If someone throws something onstage, if someone screams, it means something’s happening in that moment, and it’s your choice to do something with it,” she says. “You have to be able to let yourself go.”

Sometimes, it gets a little too real. At an early stop on the tour, when she went to cut off one of her braided extensions, she accidentally cut off part of her real hair. She runs her fingers through her scalp, rearranging her hair and laughing at herself while she tries to show me the bluntly chopped strands. “I was a little worried about how I might end up by the end of the tour,” she jokes. “But I’ll keep improvising. I’ll keep trying to make the show feel alive, even if it comes with a little consequence sometimes.”

To her, concept is everything. Songs can’t be disparate pieces; they must be part of a larger story. When she started Motomami, one of the first things that came to her was the name, a portmanteau inspired by motorcycle culture she’d grown up with in her small town of Sant Esteve Sesrovires, known for its car manufacturers and the Chupa Chups lollipop headquarters, on the outskirts of Barcelona. Her mother, who ran a metalworks company, rode motorcycles, and she wanted to convey the strength she’d learned from her and other women in her family, including her older sister Pili, now her stylist and creative director.

There was one thing she was after: “Absolute freedom,” as she puts it. “As an artist, my biggest desire is to be as free as possible,” she says. That’s what Motomami was about. “It was, ‘How far can I push to get as much freedom as possible in many ways, in subjects, in sound, in aesthetic, in everything?’”

She wanted to break out of the assumptions and expectations around her, and the constrictions of the broader pop machine that she’s noticed firsthand.

“All around me, I’m constantly seeing this phenomenon I keep being surprised by, of women and their talent in these predetermined categories: the sexy one, the crazy one, the bossy one, the diva,” she says. “But those categories don’t lead anywhere, they’re just limiting.” She thinks of musical genres the same way: “I want to escape that categorization because it doesn’t help you at all. It doesn’t help your creativity. It’s just something that restricts you, so it doesn’t interest me.”

Still, the freedom she sought wasn’t easy, especially during one of the most confining periods in recent human history. When the pandemic hit, Rosalía stayed in the U.S., working from studios in New York, Los Angeles, and Miami, while her family remained in Spain, which was enforcing a strict lockdown. “It was one of the toughest times in my life,” she says. “I wanted to go back home so bad, but I knew that if I went back, I’d be putting the project at risk. There was a high probability that I wouldn’t finish it.” So she kept grinding, leading a group of producers she admired, including Pharrell Williams, Goldstein, and Michael Uzowuru, and spent grueling hours fine-tuning every detail. Pili would call often, reminding her she kept pushing back release dates. “I would never hit my deadline,” Rosalía admits. “But it’s because I know when the music is finished.”

Small miracles came along the way: Halfway through the process, Rosalía received a gigantic library of old-school reggaeton sounds from Luis Jonuel González Maldonado, the Puerto Rican producer known as Mr. NaisGai, one of Rauw’s friends since elementary school and a close collaborator who worked on his platinum hit “Todo De Ti.” “He explained that it had been passed from generation to generation, so I really felt that that was very special material,” Rosalía says. “There was a before and after in the production after I was given that material. I could finally start to finish certain songs.”

Pharrell watched her work from the beginning. “She thinks without limitation,” he says, describing Motomami’s through line as “songs with teeth,” music that could bite you and leave a mark. “Watching her ups and her downs, her emotions, the way that she so brilliantly gave herself the therapy she needed with this album, it was equally cerebral as it was anthemic and energetic.”

One of the songs he co-produced was “Hentai,” where Rosalía chirps about the pleasures of good sex over a Disney-inspired piano melody, which Uzowuru encouraged her to play herself. She found the drums in Mr. NaisGai’s library and built them into a climax, a double-entendre embedded into the track’s core. “I whipped it until it got stiff/Second place is fucking you/First place is God,” she sings, the album’s most playful, perverse, and liberated moment. “I think there’s too much taboo with certain subjects, and that taboos restrict your freedom,” she says. “Feminine energy, there’s an erotic superiority in femininity. Why not write from there? Why not make a song from that place, where you’re owning your desires?”

Of course, the lyrics made people’s heads explode, specifically after she posted a short snippet on TikTok last January. Its explicitness shocked people used to the solemn imagery from her previous albums. But “Hentai” is Rosalía evolving again, finding new maturity and boldness in her relationships and artistic resolve. “I think before in my other projects, especially [my first album] Los ángeles, I didn’t really allow spirituality or eroticism to be a part of the project because it didn’t really make sense in my life at the time,” she says. “I just try to be open with whatever’s really happening — I think it’s the most honest way to make a record.”

Motomami is the closest anyone has gotten to the exhaustive Rolodex of sounds living in her brain. After hearing a church choir as a child, Rosalía persuaded her parents to let her pursue music. At 13, she started training in flamenco, eventually studying under the revered professor José Miguel Vizcaya. When he began teaching at a selective college program, known for accepting one flamenco student a year, she followed him and absorbed everything the school offered, from classical compositions to jazz standards. In her free time, she’d blast reggaeton with her friends, but she often holed up alone in practice rooms, poring over textbooks. At night, she’d perform at tiny bars across Barcelona and go home, where her mom would blast David Bowie.

She calls Bowie a major influence; on the song “Bulerías,” she also shouts out Lil Kim and Tego Calderon and M.I.A. “My favorite artists, you feel that need to communicate coming from them,” she says. “There’s that need for freedom first, like even if nobody was listening they would still have that need to create. You can tell that for some people that’s not their biggest goal; maybe their focus is more on money or fame. When those priorities aren’t there, there’s a surrender in that.”

Rosalía remembers an artist in Barcelona once told her that more studying, more knowledge, more influences would stifle your creativity. “That’s bullshit,” she says, still in disbelief at the thought. “I heard that when I was 19, and I knew it was bullshit. If you’re going to paint, you need colors, you need brushes, you need a canvas. The more colors you have, the more accurately you can express exactly what you want to. Knowledge never threatens creativity — it’s exactly the opposite.”

But that boundless thinking comes with difficult questions, ones that feel weightier when we’re sitting in Puerto Rico, the cradle of reggaeton and salsa, genres rooted in Afro-Caribbean communities. Motomami debuted to massive praise, yes, but her forays into cultures that aren’t her own also elicited anger. One article about the bachata song “La Fama” noted that bachata is a Black, Dominican-made genre that hasn’t gotten the recognition it deserves on its own, and Rosalía’s take “highlighted the white-washing issue overwhelming Black Latinx music.”

What she does on Motomami is to pack in references like a thesis’ bibliography, singing names out loud on the album. She says she’s eager to draw the influences in her music back to the people who created them. “I hope that with my music, other people can find the amazing artists I’m really excited about,” she says. “[Manolo] Caracol is an amazing flamenco singer, [so is] Camarón [de la Isla], but the same way I’ll name [salsa artist] Willie Colón, or Omega. I find inspiration in so many different places and styles. It’s beautiful, because I feel happy to be able to name where my references come from.”

But while Rosalía is eager to cite her sources, what does it mean that a European woman had some of the biggest bachata and merengue hits of the year? Is the industry lifting up the originators of her sounds with equal reverence? The whole debate is complicated by the fact that Rosalía works with relentless precision and rigor, but once she finishes her songs, she leaves the final interpretation to her audience.

This way of thinking has let her keep industry demands and chart pressures at bay. In July, when she released “Despechá,” it marked the biggest streaming debut of a Spanish-language song by a female artist on Spotify. But that was never the goal. “I can’t control the charts, so I don’t focus on that,” she says. “I see many people that put the focus on that, and I don’t know. I enjoy listening to music [where] I can tell the artists don’t give a fuck.”

SIX WEEKS AFTER WE HANG OUT in Puerto Rico, I meet up with Rosalía again before she performs at a small, private show at the Palladium theater in Times Square. Before I can confirm the address, I know I’ve arrived: A long line of Motomamis and Motopapis wearing mesh, leather, and harnesses coil around the entrance, a sign of how strong the Motomami cult has become.

Inside, Rosalía is standing on the stage in a plain white button-up and black pants, her face pulled into a look of intensity. While sound and lighting techs buzz around her making final adjustments, she’s all focus, tweaking the mix in her in-ear monitors until it’s just right. This is without a doubt the smallest venue she’s performed at all year; it’s probably the smallest she’s performed at since the label showcase where she was first signed. Taking a show as big as the Motomami World Tour and translating it to a room one-eighth of the size of an arena is a huge task, clearly something that’s weighing on her. “There’s an urge when I make music or go on stage that goes beyond how many people are there,” she says. “If there was one person in the crowd, I would perform with the exact same energy.”

After soundcheck, we meet up in the green room, and I expect her to be less on edge. She’s not. “I put on these shows, and I give everything. But before that, I have to get ready, I have to make sure everything is going to run smoothly. I have to answer questions and do things like this,” she says, referring to our interview. The implication is clear: She has a lot of other priorities right now. She doesn’t resent this conversation, exactly — she’s as warm and thoughtful as she’s been in our past meetings — but I can tell her mind is elsewhere.

Rosalía throws everything into her work, and the truth is, she agonized over Motomami. It explains why the moment Argentine rock star Fito Páez named Motomami the Album of the Year at the Latin Grammys this November, she burst out crying — which she didn’t do when El Mal Querer won in 2019. “When I heard Fito say ‘Motomami,’ I felt the weight of how much it took to make this project,” she says. “I felt it so fast, I felt it through my whole body, like if the summation of the last three years had hit me and made me get up and made the tears fall.”

Immediately, she embraced Rauw, who was standing to her right, and Pili, to her left. “I hugged the two people I love the most in this life, because they also know how much I had to fight to finish this album. Starting an album isn’t a big challenge if you have dreams about it, but finishing it … that’s another thing.” The fact that her peers voted for the album meant even more. “I don’t make music thinking about money, I don’t make music thinking about awards, though I appreciate if I get any of those things,” she says. “[I do it] because I know this is the reason I’m here.”

And the album, in the end, was what she needed it to be. “I feel like on Motomami, I did and said exactly what I wanted to say and do, on my own terms,” she says. “After this, there’s no turning back.”

At the Palladium, she figures out how to shrink Motomami down without sacrificing the show’s energy. The entire crowd follows her as she dances on the venue’s hardwood floor; a handful of fans join her onstage while the audience cheers them on. It’s another wild party she’s started, and once the show is over, it moves outside into the pouring rain. People dance late into the night — but by then, Rosalía is somewhere else, already living in the future.

Production Credits

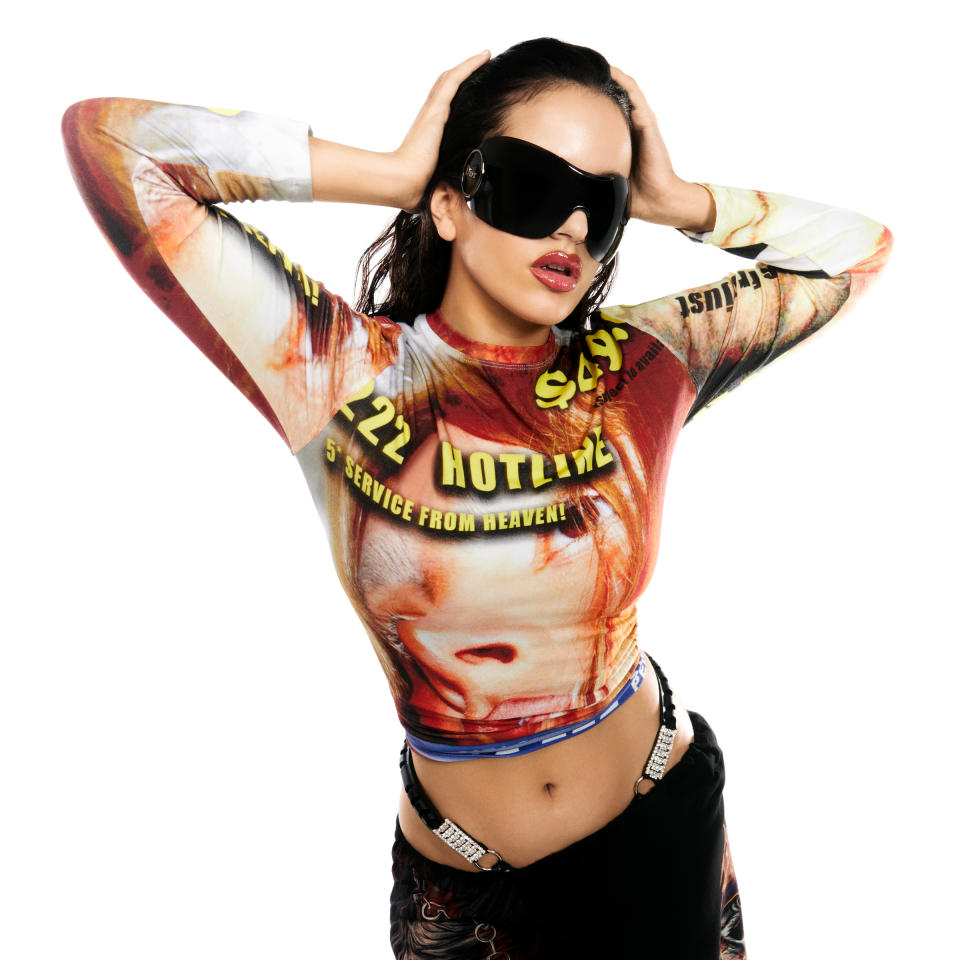

Produced by Clara Doria and Celeste Santo Domingo. Fashion Direction by Alex Badia. Photography Direction by Emma Reeves. Hair by Jesus Guerrero at The Wall Group. Makeup by Raisa Flowers for E.D.M.A. Manicure by Zaira Vega. Market Editor Emily Mercer. Styling by Joaquin Diaz. Set Design by Ignacio Vaello and Laura Roldán for Buendia Estudio. Lighting design by Camilo Diaz Salamanca. Photography Assistance by Ayelen Di Biasi and Juan David Garcia. Makeup Assistance by Eunice Kristen. Styling Assistance by Sofia Perez Millan, Camilla Tombolini, Daiana Ferreira and Maria Pia Armas Wong. Location Bubble Studios. Retouching by Bruno Rezende.

Best of Rolling Stone