Rosanne Cash Shares Her Long Road Back to Performing in New Book by Renée Fleming (Exclusive)

'Music and Mind' explores how the melodies we love can be healing for both body and soul

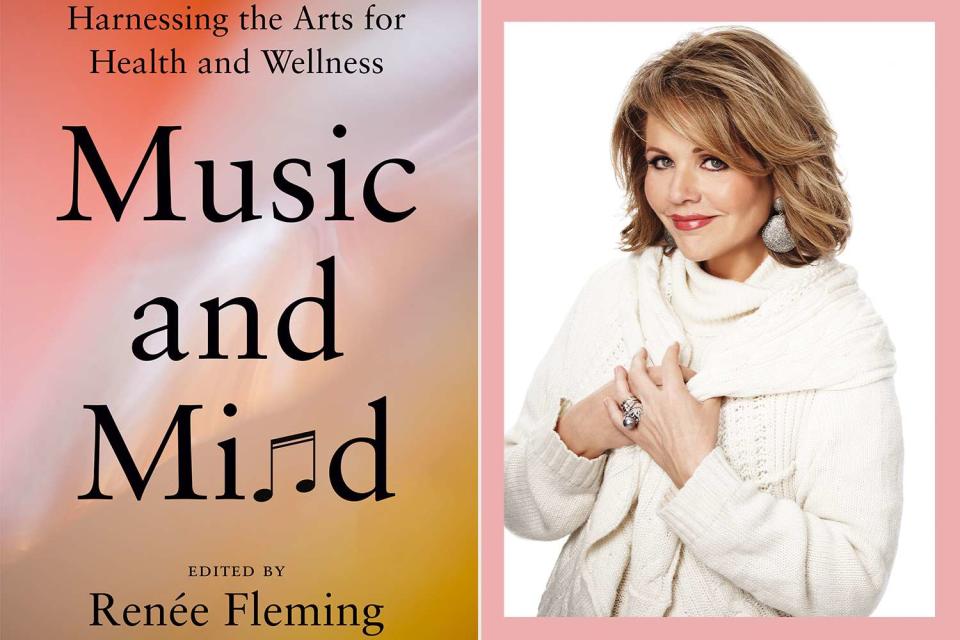

Penguin Random House; Timothy White

Music and MindMany people already know how healing music can be, but in her new book, Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health, renowned soprano and advocate for health and the arts Renée Fleming is breaking down how it works.

This curated collection of essays from scientists, artists, arts therapists, educators and healthcare providers explores the impact of music and the arts on health and the human experience, according to the book's description.

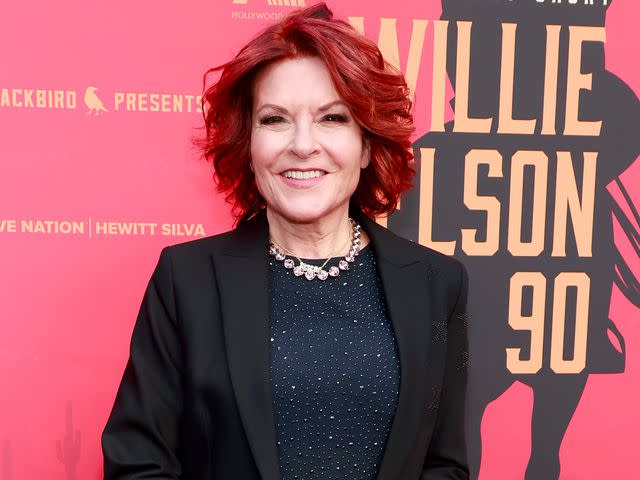

Below, in an exclusive excerpt shared with PEOPLE, Grammy Award–winning singer-songwriter Rosanne Cash shares her story of music, debilitating illness and the road back to performing.

Penguin Random House

'Music and Mind' by Renée Fleming

Around 1977 I started noticing that certain frequencies—particularly around 200 hertz—really bothered me. During sound checks for my concerts, I held my hands over my ears if that frequency went rogue and was ringing out in the overtones coming from a guitar, or bass, or the house sound. Low rumbles also disturbed me.

Then, very high frequencies started to grate on me in the studio, onstage, on the street. I was getting to the point that my range of sonic tolerance had become very narrow. The problem seemed to be affecting my left ear; it was as if that ear were having a constant anxiety attack, while my right one was doing just fine.

I loved yoga. I’d done it for 15 years, and was doing strenuous power yoga three or four times a week, but I had recently begun to find myself in pain all the time. To deal with the pain I became a spa junkie. In every town we played, if I had a spare moment, I found a massage therapist or a chiropractor who could see me.

I started having more frequent migraines, some that lasted days. I saw neurologists, one who attributed them to hormones, one who diagnosed them as “atypical migraines” and observed that my cerebellum was “hanging a little low,” and another who said I had too much stress in my life.

I gave birth to my son, Jake, in 1999, and after the epidural I received during labor, the headaches got even worse. I had a migraine-level one that lasted for months. I tried everything to get relief— meds, meditation, massage. Nothing worked.

Performing was getting harder and harder. Often I would sit in my dressing room staring in the mirror at a puffy, haggard face I barely recognized. The fatigue was pervasive, and I had lost enthusiasm for nearly everything. I just managed pain and exhaustion all day, every day.

One morning I was trying to stretch and discovered I couldn’t move. I started to cry and went to my husband John and said, “I can’t go on.”

Emma McIntyre/Getty

Rosanne Cash in 2023I came across a neurologist at Cornell in New York City—Dr. Norman Latov. He confirmed I had Lyme disease but also ordered a series of MRIs and various nerve?conduction tests. “You have a condition called Chiari malformation,” he said to me, noting it would need surgery. My cerebellum was very low in my skull, pressing into my brain stem, and the crowding was causing not only the pain, but it was affecting the autonomic reflexes of the body, like swallowing, breathing and balance. I was not in good shape.

I started consulting with neurosurgeons around the country by phone. One of the doctors I consulted pointed to my scan and said, “You see that thin trickle of white going from your spine to your head? That’s cerebrospinal fluid. It’s nearly blocked, and it’s what keeps you alive.”

I found a surgeon in New York City, Guy McKhann II, and set a date for the procedure. My sister came from Portland, and my daughter Chelsea came from Nashville. On the day of the surgery we got up early, and the babysitter arrived to take care of my eight-year-old son. I took a selfie in my kitchen— a “before” photo. I look at that photo now and am shocked at how bad I looked— wasted, exhausted and in terrible pain.

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE's free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer , from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

After six days in the hospital, I went home with morphine, steroids, a drug for nerve pain and various other potions and chemicals. I had a show booked for March, and hoped three and a half months would be enough time to recover.

My face and body were terribly swollen. I couldn’t bear to listen to music with voices. Lyrics were complicated and annoying. I was drawn to Samuel Barber, Arvo P?rt, an Chopin’s nocturnes. Looking back now, I understand that I wanted to hear melancholy compositions that tapped into my acute, aching sense of the passage of time. I felt I had lost years of vigor, joy and intimacy.

I didn’t like how I looked. I couldn’t easily climb a flight of stairs or take a walk more than a few blocks. I had a credit card–size piece of skull missing in the back of my head, filled in by what was basically Gore?Tex, and a partially removed top vertebra. I felt myself putting little pieces of a puzzle together— of memory and spatial recognition, sound and rhythm, fear and frustration, time and space.

It has taken me decades to realize that my life as a performer has been an extended, painstaking project to free myself of shame. It makes counterintuitive sense that people who suffer from shame, who have an impulse, conscious or not, to heal it and who are intensely shy and private, become performers. It’s true for me, and it’s true for many, many performers I know. It’s how we heal ourselves, as well as how we find a community of those who resonate with the inner unrest and suffering and the soul’s desire to shake off destructive limitations and expand into our potential.

John and I did do the concert that I had kept booked for March 2008. After I left the stage I sat in my dressing room shaking violently, feeling that I might come out of my body with anxiety and pain and there was a buzz in my head that was so loud I thought it must be audible to those around me. My nervous system crashed. I canceled everything else on the books until October.

Lying on the sofa a few days later, drifting in and out of sleep, an image formed in my head of me with two dear friends—Elvis Costello and Kris Kristofferson. I pictured us collaborating on something. The idea stuck, and the image kept coming back. I emailed them asking if they wanted to write something together.

We gathered at the now-defunct New York Noise recording studio downtown on Gansevoort Street with John as producer, guitarist and keyboard player, engineer Rick DePofi, bass player Zev Katz and drummer Joe Bonadio. The song was very easy to perform, and it was a comfortable, fluid recording experience.

Related: Johnny Cash's Daughter Rosanne Shares Throwback Photo of Late Singer with King Charles: 'Too Good'

While in the studio I showed Kris and Elvis the first verse of another song I had written and asked if they wanted to each write a verse. We recorded that song on the same day. I felt shaky and as if my head were in a vise, but the whole process lifted me up and gave me just a tiny peek into a possible future of recovery and inspiration.

There was one concert date on my calendar that was virtually impossible for me to remove, in October, in Bochum, Germany. October came, and my progress was not what I had hoped.

When I got to the hotel, where my bag was waiting, I stood in the middle of the room and turned slowly in a circle, trying to see through the haze behind my eyes, trying to establish myself in reality, trying to understand my life.

Later I walked into the rehearsal room and Joe Henry and Billy Bragg were there, smiling, rock and roll elegant/scruffy, happy to see me, ready to play. The first song we were going to rehearse was Bob Dylan’s “Girl from the North Country.” I lifted my head a little, and the first notes brought tears to my eyes. There was something in this world that could rouse me, something that lightened the darkness. I felt hope. That was the beginning of recovery. It was a rhythm, a melody, two gentle friends. I wrote a song for them called “Rabbit Hole”:

I just want a road that bends

a love that wins

an honest friend.

I just want a night of peace

blessed relief

I want to make you see

that you, in your crumpled splendor

when you sing to the farthest rafter

with your big life full of love and laughter

you pull me up from the rabbit hole.

Much later I participated in a conversation and performance with my friend, Dr. Dan Levitin, at a conference about music and the brain. I told him about my weird left ear, and how I had been so worried that I would lose my sensitivity and understanding of music during the brain surgery, but that after those initial couple of years of fried nerves, searing pain and hopelessness, that my sensitivity had actually increased in the most beautiful, breathtaking way, that my left ear calmed down and opened up like a blossom, that I stood at a crucial fork in my life and that music and love had guided me onto the path that fit my chosen destiny.

Shame subsided. I can’t say it’s gone, but I have compassion for myself. The girl I was went through hell, she came back, and she sings to the farthest rafter, with a big life full of love and laughter.

From MUSIC AND MIND by Reneé Fleming, published by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. “Rabbit Hole” copyright ? 2023 by Rosanne Cash.

Music and Mind: Harnessing the Arts for Health by Fleming is available now, wherever books are sold.

For more People news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on People.