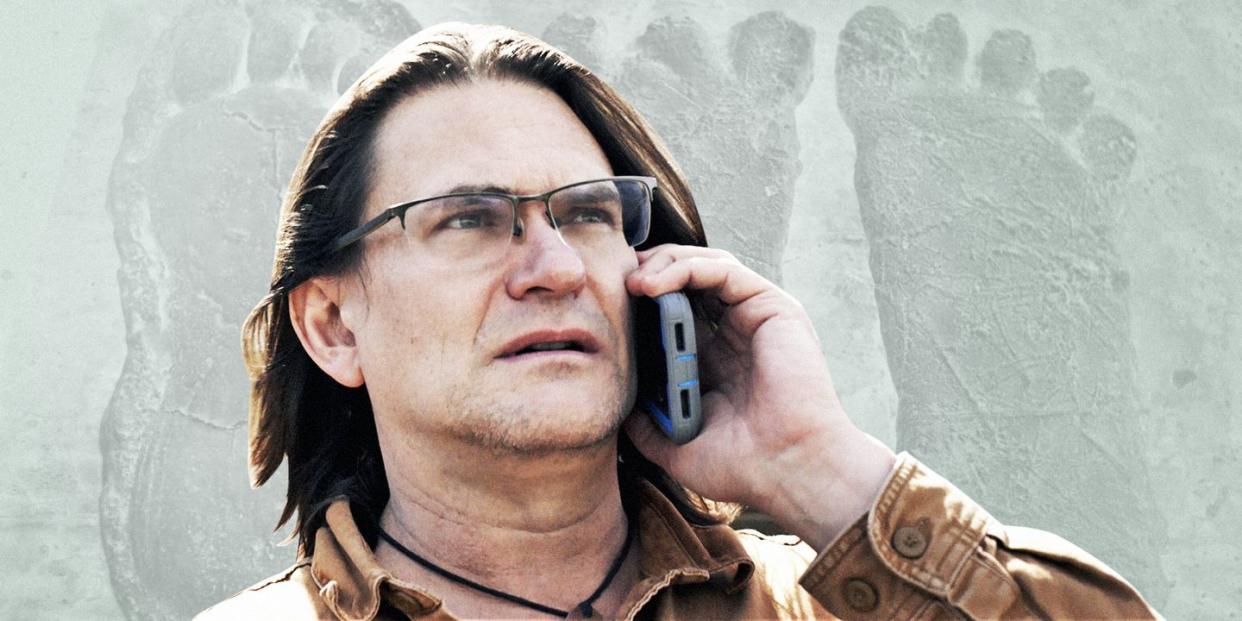

'Sasquatch' Journalist David Holthouse: 'I Got As Close to the Truth As I Can Without Getting Myself Killed'

On one of the final days of shooting Sasquatch in Northern California, journalist David Holthouse was meeting a source on Spy Rock Road. The mountain is one of the most shadowy and sinister places in the weed-growing region—remote, secluded, and notoriously violent. But the source, a weed grower who lived on the mountain, supposedly had information about the 1993 triple homicide that Holthouse was investigating for the documentary. So he went—on his own and without cellphone service.

When he got there, she began telling a story about two guys who were murdered on the property recently. As if it was comedic, she relayed to Holthouse that her dog had dug up one of the men’s boots after he was buried because he had urinated himself before he was shot, and the dog picked up the scent. “She was telling me this story like it's the height of hilarity, right?," Holthouse tells Esquire. "And on the outside, I'm like laughing along with her, on the inside I'm like, ‘I've got to get the fuck off this mountain. Is this where I pushed my luck?’”

On April 20, (yes, intentionally) the three-part docuseries Sasquatch landed on Hulu. The twisting story starts off by retelling a harrowing experience Holthouse had in 1993, when he was 23 and working on a weed farm in the Emerald Triangle. One evening, two erratic men came by the farm, sputtering about happening upon three dead men in the woods, who had been torn apart by Bigfoot. They had seen tracks, they said, and though cannabis plants were scattered everywhere, none appeared to be stolen, so it couldn’t have been a rip-off. The grower on the farm Holthouse was working on eventually calmed them down, they left, and no one spoke of the alleged triple homicide Bigfoot attack afterwards. Holthouse left the farm the following day, but the bizarre encounter haunted him in the years that followed.

More than twenty years later, his friend, documentary director and producer Josh Rofé, had become obsessed with a podcast called ‘The Sasquatch Chronicles’. And so, when Rofé texted Holthouse randomly, asking if he happened to know of any Sasquatch stories that could be turned into a murder mystery documentary, David texted back: "I got one. I'll call you in five."

In Sasquatch, Holthouse returns to the Emerald Triangle for the first time since 1993 to dig into the truth about that strange night, now with decades of dangerous gonzo journalism under his belt. It’s an active investigation that turns dark quickly, uncovering real monsters that lurk in the sketchy, little-known cannabis underworld. David Holthouse spends much of the doc alone with anonymous sources and a hidden camera, putting himself in visceral danger to follow any leads that might uncover the truth. Esquire caught up with him after the documentary’s premiere on Hulu to discuss the reactions of his sources to the series, if police action could come of it, and the scariest moment of filming for him.

Esquire: I was wondering what the reaction's been like from any of the people involved, if you've heard from any of your sources since the doc dropped?

David: Yeah, I have heard from quite a few of the sources. There's a guy in there, Ghost Dance. He loved the series, loved how he came across and was like, "Dude, you really nailed the gonzo world up here." Some of the sources whose identities were obscured have also checked in and said, "Everybody in the weed world up there is talking about this show, and for the most part, people are digging it." And people that I thought might have concerns for their personal safety don't seem to be concerned, so that's been a little surprising. The negative reactions are mostly from people who aren't in the show, but are growers up there who obviously don't appreciate a spotlight being turned on what is, frankly, a pretty dark world. There's some blowback, but not from the growers who did the show.

Do you think that the police can do anything with the information uncovered in the doc?

What I actually think the police may get some traction with is the investigation of the murder of Hugo Olea-Lopez who was killed on a weed farm out by Spy Rock Road. He's not one of the victims in the murder that's at the center of the story, but I think that there are people still up on Spy Rock that know exactly who killed that guy and why. And I think that this kind of publicity may jar loose some information, may shake some tips out of the tree for the cops, that might enable them to finally make some progress on that particular homicide. That's my hope. We met some grieving family members of his and formed a real human connection with them. I would like to see justice done in that case and I hope that this may enable some progress on that front.

How has the culture changed since the last time you were there in '93?

I think that meth is even more of a factor now than it was in the early '90s in the Emerald Triangle. And any time you introduce crystal methamphetamine, violence and a certain, what I call, meth logic, which is a certain sort of surrealist way of thinking and moving through the world, follows. And that has, I think, only ratcheted up the level of paranoia and violence in that part of the world. That was one thing I noticed. Like the weed towns up there, they're just riddled with meth, frankly, and that wasn't the case in 1993. Meth was just starting to hit in the early nineties. And it's just obviously taken hold in a big way since then. And that goes together with weed cultivation like peanut butter and chocolate. It's really in some ways the perfect drug for if you've got to stay up all night for several nights in a row guarding your patch, or if you've got like 50 pounds a weed you have to process in a space of just a few days. Crystal is a good sidekick in that instance.

The other thing that’s changed is legalization. But contrary to misconception, legalization has not resulted in a downtick in violence or a downtick in criminal activity in that region of the world. To the contrary, there's as much competition between the black market growers as there ever was and as much violence as there ever was. And the reason is, the market for black market weed has gotten more compressed, corporations have moved in, and in some regards, taken over the weed game to where they can grow massive quantities and keep their price per pound and production costs low while growing massive amounts. It has flooded the market and driven the price down for weed down, the price is really suppressed. And so black market growers are desperate and desperation translates to violence up there.

Did you go in with any expectations that were challenged? Did anything surprise you?

I was surprised by how much respect I came out of this for people who believe in Bigfoot. And I'm not one of them, but I went in with a preconceived notion that so-called Squatchers are fools. And that wasn't what I found. I found them to be utterly convincing when they were telling me of their encounters with Sasquatch, in some cases very violent, terrifying accounts. I don't know what to make of that. It rocked me back on my heels to find that I believe that they believe that they're telling the truth. And I was surprised by that. I don't know exactly what they saw and I don't know if they have some sort of unresolved trauma that in their subconscious has... what would be the word, materialized, as a Sasquatch encounter. I don't know. But it's definitely something that's worthy of a lot more serious exploration and much less just outright ridicule. I was surprised at my own reaction to that.

Was there anything cathartic for you about going back all these years later to re-examine this strange night for you?

I feel like I got as close to the truth as I can without getting myself killed. And I feel like I know what really happened and why. And so it does feel like checking a big box in that sense. And I carried it around for a quarter century wondering like, "What the fuck," you know? I have an answer to that question now and that feels good. So in that sense, it's cathartic. And it also, I hadn't really spent any time up in that part of the world since that one experience in the early nineties. That was at the very beginning of my career in journalism, fall of '93. I was just starting out. And so to circle back there now with a quarter century of gonzo investigative experience under my belt, it was like checking back in with 23-year-old me and being like, "Dude, look, you actually do know how to go after this story." Because at the time I was like, "There could be a story here," but I had no idea how to go about reporting it. And I hadn't developed the skills and the mindset yet to enable me to mitigate the risk and navigate the underworld up there. I just knew that it was outside my capabilities at that point. So it was good to be able to go back with the capability and experience that enabled me to delve into that underworld and come out with a story, and my skin intact.

You put yourself in harm's way plenty of times in the making of this doc. Josh told me about a couple instances that he was really worried about you. What were some of the craziest moments of filming for you?

I'll tell you the craziest, and there's a piece of this in the show, but not the whole experience. The craziest happened in June of last year. It was like the last investigative trip into the area, and there was this source that lived on the mountain and she absolutely wasn't going to come down off the mountain to meet me. And she had information about this triple homicide in 1993. And she lived on Spy Rock Road, this notorious part of Northern Mendocino county, super violent, dangerous place. And I went up the mountain to her weed farm to meet with her. And on the way up, one of her friends was telling me in the car about all the bodies we were passing, like as we're going further and further up Spy Rock Road, she's like, "Oh yeah, there's a body here. There's a body there, there's a body over there." You know, we're passing so many bodies, and that region has the highest number of missing persons in the United States. People just vanish off the face of the earth here more than anywhere else by far, like by a factor of four. And so it was a harrowing car ride. And then when I got to the farm 30 minutes in, this black market grower, she starts telling me this story about these two guys that had, about a year or two ago, had come up from L.A. to make a dope deal. Somehow it went wrong, and they were murdered on her property and they knew they were going to be murdered before they were shot to death. And one of the guys, as he's waiting to be executed, pissed himself, and they shot him and buried him there on her property. And after they buried him the next day, her pit bull, there's all these pit bulls running around, one went and found one of the guy's bodies and dug up his piss-soaked boot and brought it back and dropped it at her feet like, "Look what I found." And she was telling me this story like it's the height of hilarity, right? And on the outside, I'm like laughing along with her, on the inside I'm like, "I've got to get the fuck off this mountain. Is this where I pushed my luck?" Because my concern was always that I was going to wind up face-to-face with one of the killers and not know who I was talking to. My concern was always that my yearning for information was going to get me killed in the sense that the killer would know I was getting close to the truth and would use that to set me up by having somebody be like, "I've got key information for you, but you got to come up the mountain to get it." So I was always concerned that I was going to walk into a trap, and it was always a calculated risk. And I'm really glad that I had Josh there to pull me back from the edge a few times, because left to my own devices, I probably would have pushed it and I probably would've pushed it too far.

Chasing down real-world monsters is a recurring theme in your work. We talked a bit about the police hopefully having a breakthrough in Hugo Olea-Lopez’s missing persons case, but in the main case of this doc, prosecution isn't really a viable path. I was wondering how you find resolution when your work can't lead to prosecution or justice in the traditional sense.

It’s tricky. I still don't know for sure whether a triple homicide actually occurred in 1993. I think it's far more likely it did than not. If it did, I got various accounts of the motive for those murders. And one of the potential motives was like vigilante justice for a gang rape. And if that's the case, I got no problem with that. I think justice would probably be done. Without knowing for certain the whole truth behind the murders that may or may not have happened, I can't say what justice would even look like.

The number of missing women and especially missing Indigenous women in that area is terrible. It's terrible and it's terrifying, and it just doesn't get the attention that it deserves. So if there's justice to be done, I hope this series will bring to light that pretty horrifying trend of all the people that are going missing up there and have been for decades, and especially all of the women, and even more especially, all of the Indigenous women up there. It's a hidden, suppressed crime trend that deserves more attention from law enforcement and from the greater public.

Absolutely. What was your biggest takeaway from creating the series?

I guess there's a couple. One is that weed is a fairly benign drug substance compared to other hard drugs, but when you look at what goes into producing weed, it's actually just as dangerous in terms of the drug world as coke or meth, in my opinion. The biggest takeaway for me was that the stereotype of old time hippies growing weed on their organic farm up in Northern California, that exists, it's always existed up there. But that's not the dominant criminal subculture up there. The dominant criminal subculture is a very dark and dangerous place. It's biker gangs and cartels and some really, really serious cats doing business up there. And that most people who are smoking weed, even legal weed from dispensaries, have no idea how much blood is fertilizing those plants in a metaphorical sense. That's one takeaway.

The other is that I keep coming back to how convinced some of these people that claim to have seen Sasquatch were. My personal opinion is that maybe this is some unresolved trauma. I think that there is a serious show to be done about people claiming to have encountered cryptozoological creatures, or cryptids. I think there's a show to be done, like a serious examination that's not a sensationalist hunt for Bigfoot. It's really like, what's going on here? What is driving all these people to believably claim that they have seen these creatures? I came out fascinated by that.

What's next for you?

I'm working on a play right now that's about my experiences working undercover in the neo-Nazi movement. And there's something to this idea that's at the heart of Sasquatch about revisiting my own past that I find compelling, and apparently viewers do too. And so there's a couple stories that I reported in the 1990s or the early 2000s that have continued to haunt me over the decades. I would really like to have a second crack at some of these murder mysteries, and hopefully get a chance to reinvestigate them. That would be great.

You Might Also Like