How Sean Connery, an Unlikely Choice to Play Bond, Defined 007's Style

It is no little irony that the lasting, iconic style of James Bond, the yardstick against which all Bonds are compared, should first have been personified by Sean Connery. The rough-hewn actor, one-time milkman, and bodybuilder from Edinburgh had not been the producers' first choice for Bond. That was reserved for Roger Moore. But Moore was tied up with a contract filming The Saint for TV and already a star. If not quite the establishment man that Ian Fleming outlined for Bond—private schooled, upper crust stock—in his taut novels, Moore was suave, well-groomed and at least sounded the part. In comparison, Connery was a bit of rough.

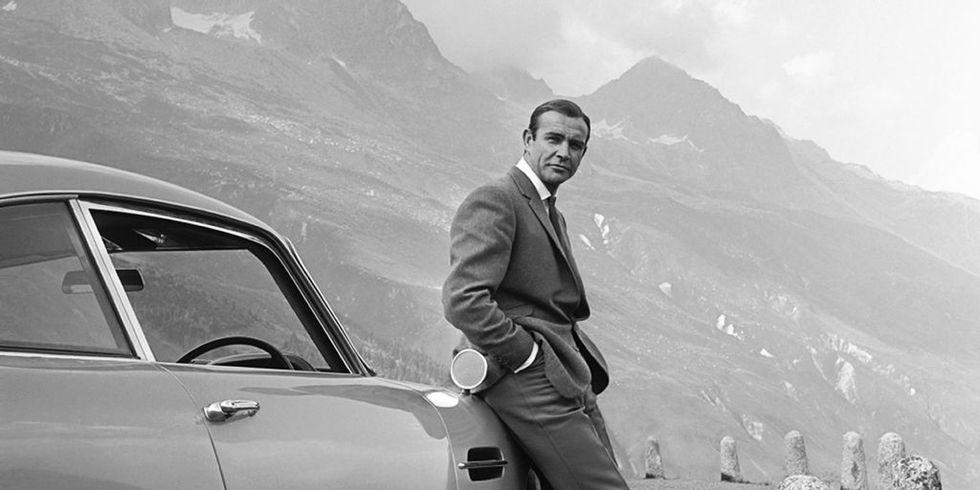

So, the director of the first Fleming novel to hit the screen, Terence Young, set about— Pygmalion like—to polish Connery up, and knock off the rough edges. In 1996, I co-wrote a book on the style of James Bond, titled Dressed to Kill, that tracked the sartorial evolution and impact of 007's fashion. Ian Fleming wrote relatively little about Bond’s style, sketching in only the briefest of descriptions while devoting pages to the overblown outfits of Bond’s foes. A little goes a long way. Terence Young took Connery to Anthony Sinclair, a tailor on London’s Conduit Street at the northern end of Savile Row. Sinclair was Young’s tailor. He specialized in what he called the “Conduit Cut,” a fitted hourglass shape to the jacket that suited fit, military men. It was deliberately at odds with the boxy fashion suits worn by most young men at the dawn of the swinging sixties. Cutting like that stood out as slightly behind the times but reassuringly expensive.

Next Young took him to Turnbull and Asser, his shirtmaker on Jermyn Street several blocks away south of Piccadilly. There, Connery was fitted with the same pale blue cotton poplin shirts and knitted navy silk ties that Young wore day in day out himself. It was Young who gave Bond his turned back “cocktail” cuffs, a sartorial detail that at the time defined a man as both well-to-do yet rather rakish.

Bond’s style was extremely precise, the spare but expensive, handmade wardrobe of a military man, not overtly fashionable but not fuddy-duddy, either. It met and exceeded accepted standards of dress while remaining deliberately unsensational. Fashion in all its preening frivolity was always reserved for Bond’s vain, egotistical nemeses like Goldfinger, Blofeld, or Largo. As a recipe for worry-free style, Connery’s Bond defined and still defines the clean-cut ideal of a wardrobe that transcends fashion and becomes eternal.

If Bond was the establishment man in town, the exotic and tropical locations around the globe were the backdrop for him to get a bit more experimental with his off-duty wardrobe. It didn’t always work. That said, Connery fares better than all succeeding Bonds as his wardrobe for the beach is still as spare and restrained as his working day clothes. Later Bonds fall prey to the gravitational pull of fashion and pay the price. Roger Moore suffers from this and unfairly, I think. It’s not his fault he got the gig in the hedonistic 1970s. But just about the only thing Connery’s Bond gets wrong is in Goldfinger, where he appears in Miami in a sky-blue terry-cloth onesie. Somehow, he gets away with it.

In the end it was a cocktail: Connery’s suave style with his own rough edges poking through that gave Bond his bite. It resonated with the socially and geographically expanding world of the 1960s; Connery was a forerunner of a whole generation of working-class British actors made good—like Michael Caine and Terence Stamp—who personified a rougher and racier sexuality on screen. In clothing terms, Connery’s Bond gave all young man an easily referenced visual encyclopedia of how to dress well without ever overdoing it.

You Might Also Like