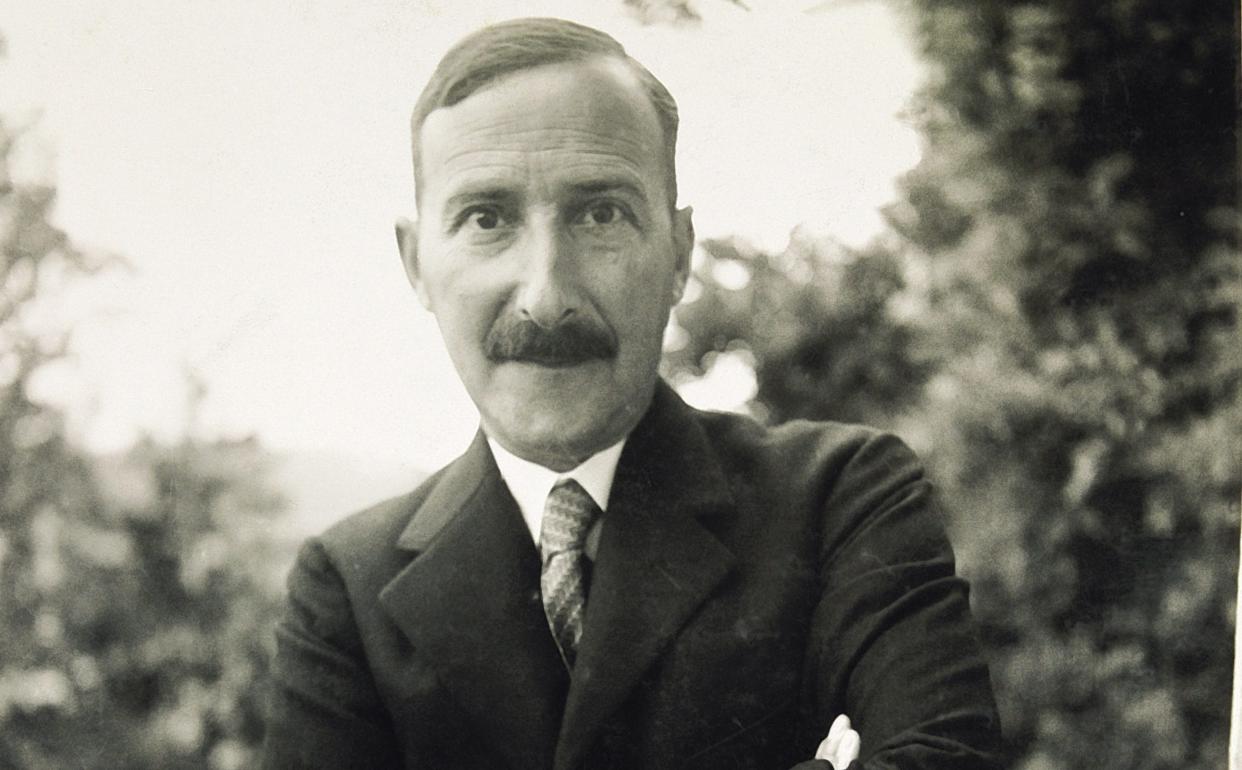

‘Sexual passion frightens me’: the tragic, romantic life of Stefan Zweig

In 1912 the Austrian Jewish writer Stefan Zweig received a letter from an unknown woman in her late 20s. She was an admirer, she said, but omitted to mention a husband and two children. “I am not writing in the expectation of a reply,” she concluded, “though it would give me great pleasure.” After the war, and a divorce, she became Friderike Zweig.

In 1922 Zweig, perhaps inspired by his wife’s forwardness, published what would become his most famous story. Letter from an Unknown Woman, later filmed by Max Ophüls as a Hollywood tearjerker starring Joan Fontaine, tells of a young woman who sends a fascinating letter to a famous Viennese author. As a child, she explains, she was his doting neighbour. Without revealing her identity, as an adult she tempted the author into a night of bliss. But when they meet again a year on he has no memory of her, and now she is going to end her life.

If the story had an aroma of autobiography, more strikingly still it contained a prophecy. Zweig married a much younger woman in 1939. Three years later, with no prospect of Hitler’s defeat, he and his second wife Lotte would kill themselves. He was 60, she was 34.

Their joint suicide in the Brazilian hill town of Petrópolis now feels like a remote tragedy beyond memory. But there is one person still alive who knew the Zweigs well. Lotte’s niece Eva Altmann will be at Hampstead Theatre when Christopher Hampton’s new adaptation of Letter from an Unknown Woman opens. I know this because Eva, a small woman with a watchful birdlike presence, is my second cousin once removed.

“Lotte wasn’t a passionate person,” she tells me, “but it was a very close and a very warm relationship.” The Altmanns were refugees from Germany. Lotte met Zweig through a Jewish aid organisation when he advertised for a secretary. They soon fell in love.

Eva remembers Zweig’s flat close to the British Museum as “rather dark and slightly gloomy”. Whenever she visited she would become an infant under-secretary. “Lotte typed everything but she always had carbon copies and they had to be sorted and collated and that was the job I was given whenever I was around.”

She recalls being taken to Covent Garden by Zweig to see Don Giovanni, and being shown treasured items from his collection of autograph manuscripts, including Mozart’s catalogue of his own works. Three days after the declaration of war, Zweig and Lotte married and moved to Bath. Eva, then 10, and another young cousin joined them.

“The rule was that at meal times we had to speak French,” Eva says. “I think it had a double function. It was quite an effective way of keeping us quiet. But language was very important to him and he expected other people to be able to speak other languages too.” She still has the charming letter to “Dear Evula” in which Zweig glides between English and French, Italian and German.

It was through learning German at school in the mid-1960s that Hampton came across Zweig. “I started to seek out more stuff that he’d written,” he says. “Then I went to see the film and was very very marked by it. About 25 years ago I watched it again and suggested to Andrew Lloyd Webber [with whom he adapted Sunset Boulevard] that it might be a good subject for a musical, and he decided it wouldn’t.”

The story lingered in his mind until Theater in der Josefstadt in Vienna, which had staged Les Liaisons Dangereuses in 2007, proposed that he adapt Zweig’s The Royal Game. He counter-proposed Letter from an Unknown Woman.

“It is about an obsession,” he says, “and I always think people with obsessions are very interesting onstage, which is why I felt it would adapt well.” Directed by Hampton, it closed after only one preview in March 2020, but made a successful return after lockdown.

The Hampstead production is the latest development in the Zweig revival. The most translated author in the world before the war, after it his reputation plummeted in the UK until 1998 when Pushkin Books began publishing his biographies, his fiction, and The World of Yesterday, the nostalgic memoir he completed the day before his death.

“I think Stefan Zweig’s great sin was that he was too popular,” says Hampton. “It’s quite analogous to Somerset Maugham who was so wildly popular that people assumed he must be second-rate. He was extremely generous to other writers. Joseph Roth never failed to pay him back by being rude about him in cafes. Thomas Mann is particularly condescending about him. The fact that he was a writer on their level never crossed their minds.”

Mann continued defaming both Zweigs after their suicide. “He can’t have killed himself out of grief, let alone desperation,” he railed. “The fair sex must have something to do with it.”

Eva, evacuated to the US, was 12 when she heard the news. “I don’t think I was terribly surprised,” she says. “I think you’ve got to put yourself into the war situation. People were dying right, left and centre. I never really took in how young Lotte was till much later. But she wouldn’t have wanted to go on living without him.”

Her parents took on the burden of running the Zweig estate, but after they died in a car accident in Switzerland in 1954, the responsibility fell on Eva in her mid-20s. She still has the books Zweig left behind in Bath, but the manuscript collection was passed to the British Library in 1986. Did she consider returning the entire collection to Vienna? “I wouldn’t have dreamt of it,” she said. “They forced him out. Quite a lot of the country supported the Nazis. They welcomed them when they marched in.”

Hampton sees Visit from an Unknown Woman, as he has retitled the story, as the completion of a stage trilogy about Fascism’s emergence – “when society went from saying it can’t possibly happen to suddenly being in the middle of it.” The first in 2009 was an adaptation of ?d?n von Horváth’s novel Youth Without God, written when he could no longer get his plays on in the 1930s. In 2017 came A German Life, starring Maggie Smith as Goebbels’s secretary.

Zweig is not quite a newcomer to the English stage. He features in Collaboration, Ronald Harwood’s 2008 play set during the rise of the Nazis when Zweig wrote the libretto for Richard Strauss’s opera Die schweigsame Frau. At the time, I remember Eva saying it helped her to see it as fiction that, absurdly, the actress playing her aunt was blonde.

Hampton’s big decision is to make Zweig a character in his own story. In 1948 Ophüls, who was a German exile, transplanted his film from the 1920s back to the era of Hapsburg swagger. In Hampton’s version it’s 1934. The unnamed writer, not identifiably Jewish in the story, is now called Stefan and clearly heading into exile.

“I’ve always assumed that the story has an autobiographical root to it,” he explains. “The idea of having forgotten someone you had a sexual relationship with is so ungraspable that it must have come from personal experience.”

Zweig’s diary certainly hint at sexual incontinence. “I shudder at my own virtuosity,” he once wrote. “I get into conversation… with a woman, a sculptress, and the next thing she knows she is in my rooms at four o’clock in the morning and sharing my bed.”

Lotte was sharing Zweig’s bed after four o’clock in the afternoon when a maid and her husband pushed at the door to reveal an older supine man wearing a jaunty moustache and a punctilious tie and a young woman in a cotton dress. She was rolled over on her side and her body was still warm.

Visit from an Unknown Woman runs at Hampstead Theatre until July 27; hampsteadtheatre.com