She Faked Her Chimp’s Death. Then Things Went Apeshit

Tonia Haddix is nearly in tears.

It’s been only a few days since officials showed up to the exotic-animal broker’s Missouri home on June 2, after PETA received a tip that Tonka, a Hollywood movie-star chimp in his thirties that Haddix claimed had died in May 2021, was, in fact, alive.

More from Rolling Stone

As Escalating Violence Hits Atlanta's Music Industry, a Shaken Hip-Hop Community Seeks Solutions

A True-Crime Star Lost His Podcast Over Misconduct Allegations. Then, More Women Came Forward

New Reward Offered for Lady Gaga Dog Walker Shooting Suspect Accidentally Released from Jail

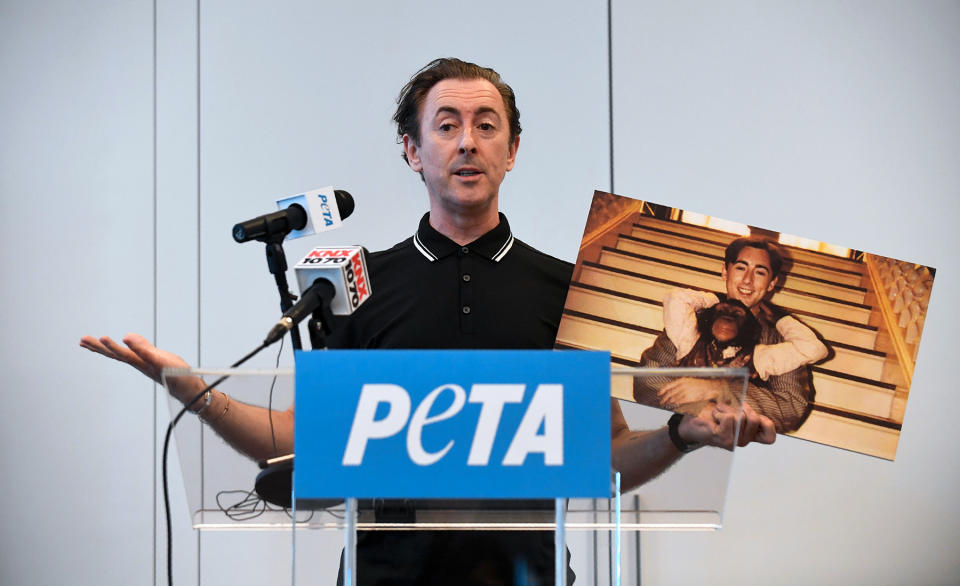

The 52-year-old had blatantly lied to PETA, a judge, and multiple media outlets, saying that Tonka, who starred in George of the Jungle and Buddy alongside Alan Cumming, had died of heart failure. In reality, she had been stashing the chimp in her basement to avoid giving up Tonka with her six other chimps that the judge ruled were being kept in unsafe conditions.

It’s been an emotional ride for Haddix, who speaks with Rolling Stone a day after authorities took away Tonka and four years after her extensive legal battle with PETA began. “Tonka is the love of my life,” she says. “He really, truly is. I love him like a son.”

The insanity of the saga — an acting chimp, an elaborate hoax, a messy lawsuit, $20,000 in reward money, and the brief involvement of the attorney for Kyle Rittenhouse and multiple alleged Capitol rioters — naturally made national headlines. It all seemed like a fever dream, reminiscent of Tiger King — with the added mystery of who exactly turned in Haddix, which eventually pointed back to a documentary crew who had been filming Haddix for the past year.

And at the center of it all was Tonka, whom Haddix claimed was in such bad shape from congestive heart failure that her vet had recommended euthanizing the chimp to spare him any more suffering.

Willing to go to any length to protect him, Haddix says she only wanted what was best for the chimp and to be by his side when he died. As she admits, she wound up lying under oath, roping in friends to hide and watch after him, attempting to find ways to fake DNA-test results, and claiming she offered federal marshals bricks of $10,000 in cash to pretend they saw nothing when they arrived at her home with an emergency court order. Now, she faces up to five years in prison if she’s hit with criminal perjury charges. (“I don’t care what they do to me,” Haddix says of possible prison time. “I just care about that kid.”)

But in perhaps the strangest twist, according to PETA, Haddix was considering euthanizing Tonka when, PETA claims, there is no evidence to suggest he had even been close to death. (Haddix insists Tonka was close to death and denies that she was immediately going to euthanize him.) As Brittany Peet, PETA’s deputy general counsel for captive-animal law enforcement, tells Rolling Stone, “virtually everything that comes out of Tonia Haddix’s mouth is a lie.”

Whitney Curtis for Rolling Stone

As bizarre as owning a pet chimpanzee might sound, at least 15,000 primates exist as pets throughout the country, according to the Animal Welfare Institute. Where they can be owned differs state to state, with more than half outright banning or severely restricting the private ownership of exotic animals. (Missouri has relatively lax laws concerning animal ownership.)

Still, keeping chimpanzees as pets is a highly contested issue. Due to chimps’ extreme intelligence, immense strength, a tendency to become violent as they reach adolescence, a critical need for socialization with other chimps and spacious enclosures, virtually all primate experts agree that they should never be kept as pets.

Keeping chimps in unstimulating environments and apart from other apes not only poses a safety threat to humans, but also to the animals themselves, causing them extreme distress. Out of concern for the animals’ welfare, PETA was so adamant on removing chimps from Haddix’s care back in 2019, and why it continued the search for Tonka even after Haddix claimed the chimp had suddenly died.

For more than a year, Haddix kept the boldfaced lie going — a remarkable feat for someone who claims they are actually a terrible liar. “Anyone that knows me will tell you I’m the most open book that they come by,” she says. “It was hard for me. I think that’s probably my downfall, because I’m not a good liar. If [someone I knew] asked me the question [about Tonka], I would tip my eyes. I mean, come on, everybody knew.”

Candid to a fault and with an eccentric personality — “anybody that has an exotic has to have some kind of screw loose,” Haddix acknowledges — the former nurse describes herself as born to be a caretaker. (She recalls drop-feeding her beloved capuchin monkey Carter for every meal until his death last year.)

The mother-of-two is a self-professed “girl’s girl” who cries easily, even over a small monkey’s broken arm. She likes a good meme, with her Facebook page filled with cheeky chimp pictures and MAGA humor. Surprisingly, Haddix says she’s not necessarily a big animal lover, with her affinity specifically aimed at dogs and primates. (Although, she adds, she does like wallabies.)

“I don’t care what they do to me. I just care about that kid” – Tonia Haddix

Her other Achilles’ heel, she says, is being too trusting of others. It’s partially the reason, she says, she opened up her life to Dwayne Cunningham, who, according to his Facebook page, is a former Ringling Bros. circus clown and animal-sanctuary worker, and is an animal lover, who Haddix claims approached her around last June with a pitch for a documentary that she was told would support the private ownership of exotic animals. (Cunningham did not reply to repeated attempts for comment.)

Reluctant to work with any type of documentary crew, and even warned against the idea by close friends, Haddix says Cunningham won her trust because he was “a big animal person.” “That’s why I trusted him, because he would even come out early just so he can help bottle-feed some of our baby hoofstock,” she says.

Haddix brought Cunningham and his team into her world, claiming that the crew knew Tonka was alive the entire time. Rolling Stone reviewed a February text message between Haddix and a number saved as “Dwayne,” with the latter writing, “We’d like to interview some animal people you know about you defeating PETA and if that gives them any Hope for the future,” a reference Haddix understood to be about successfully hiding Tonka from PETA at the time. In another text conversation with Cunningham, Haddix appears to talk about trying to find an expert willing to fake animal DNA-test results.

They communicated frequently, with Cunningham sending her chimp memes and Haddix complaining about PETA. In late May, Cunningham called Haddix and spoke to her at length about Tonka’s alleged worsening health. Haddix subsequently agreed for the crew to visit her in early June.

That conversation wound up being the tip that PETA got later that month that revealed Tonka was alive: A 28-minute recording of a May 22 call between Haddix and Cunningham about the documentary. (Texts reviewed by Rolling Stone show a number saved as “Dwayne” setting up a call with Haddix for that exact date.) The recording confirmed the animal-rights group’s hunch all along, which it had tried to uncover by putting out a $20,000 reward in April with Cumming for any information about Tonka’s whereabouts. (No one has claimed the reward, PETA said.)

According to a 10-page transcript of the call reviewed by Rolling Stone, Haddix spoke with Cunningham about Tonka’s supposed congestive heart failure and told him her vet would be examining the ape on June 2, possibly euthanizing him if his condition wasn’t improving.

“I mean, he’s going to make me stand firm on the appointment because he don’t think I’m being fair to Tonka,” Haddix is quoted as saying.

“So, he would come there and give him the injection?” Cunningham asked.

“Yeah, he’s supposed to be sending me some [valium] and stuff over so I could give it to him before he comes,” Haddix replied. “So, he’ll be relaxed.”

“Yeah. Maybe we could interview your son and be around then at the same time,” Cunningham later said. “Let me run it by everybody, but that would work.”

“Because that’s the end of the legacy,” Haddix added.

“I should be able to do that for Tonka,” Haddix said at another point in the call. “But I just don’t know if I can. I’ll be honest with you: I don’t know that I can let him go. And that’s the sad part is because I’m being selfish, and I know it. You guys don’t know how much I love him.”

Haddix claims Tonka was “spoiled rotten” with a 60-inch TV, an iPad-like device, and occasional McDonald’s Happy Meals.

It would be another two days after federal marshals arrived at her home before Haddix realized that PETA’s tip had come from someone aware of her call with Cunningham. She tells Rolling Stone that she didn’t know that he had been recording their conversation.

“I’m beating myself up because if I put Tonka in jeopardy just because I was doing a documentary thinking it was going to be for the betterment of private ownership, then look at what I did,” Haddix says.

Haddix claims that Cunningham denied to her that he had turned her in, but allegedly admitted to her that the film crew had recorded him while on the call. Still, she says, he claimed to not know who would have submitted the recording to PETA.

Haddix had more questions, including who Cunningham was working with. She says after asking repeatedly, Cunningham finally told her the production company was “Voice of America, Pro Animal Ownership Group,” as confirmed by a text message reviewed by Rolling Stone. But Haddix says she remembers one slip-up by a member of the film crew that pointed to someone she wanted nothing to do with.

Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images

While Haddix claims Cunningham was transparent about there being financial backing for the film — flights, hotels, and camera- and sound-equipment rentals are all costly expenses requiring deep pockets — he was allegedly cagey about exactly who was funding the project. “He did say they did have some financial backing, some people that were animal people,” Haddix says. “He did always allow me to know that it was supposed to be a bigger, grander scheme of things, but he always assured me that [the documentary] was pro-private ownership because they all felt the same way.”

Recalling the one slight blunder by a member of the film crew, Haddix tells Rolling Stone someone allegedly made mention of an “Eric” having some questions. “That threw up a red flag for me,” she says. “I said, ‘Wait, is that Eric Goode? And he’s like, ‘Oh, no,’ but he wouldn’t tell me his last name.”

The “Eric Goode” who Haddix feared was involved in the project is the same Goode who co-directed Tiger King, the batshit Netflix series about Joe Exotic that became a sensation in early 2020, spawning a scripted Peacock series, a catchy parody of Megan Thee Stallion’s “Savage,” and landing the woman at its center, Carole Baskin, on Dancing with the Stars.

Despite Haddix claiming the film crew member denied Goode’s involvement in the documentary, Rolling Stone obtained LLC filings for a company called Voice of America that names Goode as the manager. It happens to bear the first part of the company name that Cunningham said was working on Haddix’s documentary — Voice of America Pro Animal Ownership Group. Formed in September 2021, the firm is listed as a film-production company and shares an address with Goode’s other production company, Goode Films. (Goode did not respond to requests for comment.)

Out of the three film-crew members who Haddix identified as being involved with the project, two have direct ties with Goode’s Turtle Conservancy, including one who was credited as a camera assistant on Tiger King. (When reached by phone, two film-crew members confirmed to Rolling Stone they had worked on the project, but distanced themselves by saying they were working in a freelance capacity or had barely met Haddix.)

A Goode Films source who was privy to information about the documentary’s production confirmed to Rolling Stone that Goode’s team was behind the project. The source claims they were aware that concerns had been raised by the crew about feeling “disturbed” by the state of Tonka’s care. The source also alleges there were discussions among the production team over being “uncomfortable” with the ethics of Haddix being in the dark about who was behind the documentary. Believing the information was purposely withheld, Haddix says she would have never participated in the documentary if she knew Goode was involved.

Goode was previously accused of misleading documentary participants by Baskin and her husband, Howard Baskin, who claimed Goode and his production partner deceived them into participating in Tiger King. They claimed they believed the documentary would be the Blackfish-version of “exposing the bad guys” of the big-cat community. (Goode previously denied that Baskin was duped, telling the Los Angeles Times in 2020, “[Baskin] knew that this was not just about [big cats] … she certainly wasn’t coerced.)

In a statement to Rolling Stone, Howard Baskin writes that he found it an “outrageous lie” that Goode and his partner had claimed they were “forthright” with Tiger King’s participants. “I heard that and wanted to send them a dictionary with the ‘forthright’ page tabbed,” he writes. “In my opinion, [they’re] people who are simply missing whatever gene in the DNA is responsible for giving us any moral values or integrity. Totally missing.”

There’s no clear-cut code of ethics for documentarians to abide by, explains Stacey Woelfel, a professor at the Missouri School of Journalism and director of its documentary program. But there are general expectations. “If there’s anything that comes close to a code of ethics, it’s that you should create trust and treat your characters and participants with respect,” he explains. “The other half of that is you should treat the audience with respect.”

Award-winning documentarian Dan Birman, president of Birman Productions and a documentary professor at University of Southern California Annenberg, adds it’s a filmmaker’s “responsibility to be as transparent as humanly possible.”

Feeling misled, and now wary of the documentary’s direction, Haddix speculates that, if indeed someone in the crew had turned her in to PETA, it was possibly done to amp up the project’s drama. She has vowed to make sure the project never comes out. “I’m gonna stop that production,” Haddix says. “It’s not gonna happen … it would be under false pretenses. There will be none.”

Whitney Curtis for Rolling Stone

Tonka’s home in Haddix’s basement now sits empty. Painted in bright primary colors, his enclosure was surrounded by brick walls and a glass window that opened up to the rest of the basement.

Haddix claims he was “spoiled rotten” with a 60-inch TV, an iPad-like device, and occasional McDonald’s Happy Meals. She even bought Tonka a new hammock and swing, which Haddix says he showed little interest in.

He didn’t have many visitors besides Haddix and a handful of trusted close friends — outsiders couldn’t be trusted, she says. Those who were privy to Haddix’s secret, attended parties she threw for Tonka, such as a St. Patrick’s Day bash, where Tonka was seen in Facebook photos wearing a festive hat and leprechaun headband. For Easter, he drank soda and was given a basket filled with M&Ms and other candies.

But human contact was limited, and by Haddix’s own admission, she wouldn’t get in the cage with Tonka in case he got “upset.” In the past three decades, there have been more than 450 incidents of privately-owned primates injuring or killing people, according to PETA. “As they age out of being these cute, cuddly infants, they reach sexual maturity and can become highly aggressive, very unpredictable — essentially being the wild animals they’re meant to be,” explains Kate Dylewsky, a senior policy adviser at the Animal Welfare Institute.

“To deal with this, private owners will often keep them in cages, tethered [and] confined,” Dylewsky adds. “It’s really an awful life for animals that have such sophisticated existences in the wild.”

As a result of the animal’s distress due to isolation and unstimulating environments, “you’re going to end up with chimps that are depressed [and] go into mental disparity, where they have to entertain themselves constantly throughout the day,” says Ali Crumpacker, executive director of Project Chimps.

“That can create all sorts of psychoses, where [they] pull out their hair because they’re so in need of stimuli. They’re actually causing pain to their own body to just have something exciting going on in their day.”

Haddix not only didn’t provide Tonka with a proper living environment, PETA’s Peet says, but by faking his death, she also prevented him from joining his partner, Tammy, and the rest of his chimp family at the sanctuary they were sent to. (Tonka was sent to Save the Chimps sanctuary, while the other six primates were sent to the Center for Great Apes.)

“What [Haddix] did to Tonka had nothing to do with Tonka,” Peet says. “It was pure selfishness … she denied Tonka not only the companionship of other chimpanzees, but she took him away from his family,” Peet adds, also citing the lack of nutrition and exercise Tonka was receiving.

But Haddix sees things differently. Citing her bond with Tonka, who she frequently refers to as her “child,” Haddix says going without human interaction will kill him. “If anybody knows Tonka, Tonka is not a normal chimpanzee,” she says. “He doesn’t act like another chimpanzee; he loves people.”

Ultimately, under Missouri state law, Haddix says she was completely within her rights to own Tonka and whatever animals she believes she can properly care for. “Tonka was my chimp legally, and even though a judge did not agree with that, I did not agree with her,” Haddix says. “I felt I had to [fake his death] to protect him, because I didn’t feel like we got our fair day in court. If you can’t beat the system, you got to go by what you think is the right thing to do.”

Differing state laws is why the Animal Welfare Institute, PETA, and other animal-rights organizations have thrown support behind the Captive Primate Safety Act, which would make it illegal at the federal level to buy or transport primates across state lines — significantly clamping down on people obtaining primates as pets.

Until the bill is passed or state laws change, some citizens are legally allowed to own their chimps, no matter how unethical or harmful experts might deem the practice. It’s turned animal-rights groups into watchdogs to ensure the animals are being well-cared for. If there’s an inkling of mistreatment, poor living conditions, or certain animal-act violations, the owners could be forced to relinquish their exotic pets.

“I had to [fake his death] to protect him, because I didn’t feel like we got our fair day in court” – Tonia Haddix

That’s exactly how Haddix ended up clashing against PETA, although the nonprofit was first suing Tonka’s original owner, Connie Casey, hoping to see her chimps relocated to an accredited sanctuary.

Casey and her ex-husband, Mike, owned and operated the now-defunct Chimparty, later tidily renamed the Missouri Primate Foundation. Located in Festus, Missouri — about 30 miles south of St. Louis — Casey had put her animals to work, renting out young chimps for birthday parties, photo shoots, and even movies. One of Casey’s chimps, Connor, was pictured on several Hallmark cards, according to PETA.

Casey’s facility was reportedly one of the largest breeders of chimpanzees in the country, fetching up to $50,000 for a young chimp. By 2009, Casey claimed she had sold up to 20 chimps. “For decades, this despicable outfit was ground zero for chimpanzees who were bred and sold as props and pets,” Peet said in a 2016 statement announcing the group’s intention to sue Casey.

PETA’s suit against Casey was based on what it alleged in court documents as the “unlawful and inhumane conditions” at the Missouri Primate Foundation. The compound was a lightning rod for violations, according to PETA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Between 2011 and 2016, the USDA found numerous sanitary violations on the premises, according to court records reviewed by Rolling Stone.

“Debris, flies and roaches remained common throughout the facility, there was excessive food waste and trash in the enclosures, feces buildup on barrels in the enclosures and encrusted on the chimpanzees’ feet,” PETA claimed in a 2017 legal filing against Casey, noting she had 16 chimps under her care in 2016.

Casey’s foundation also deprived her chimpanzees of crucial social interaction by keeping them isolated from one another, the USDA claimed, according to filings in PETA’s suit against Casey. The organization found the facility was not an adequate environment for the chimps, causing some of the animals to “show signs of being in psychological distress through behavior and appearance,” according to the PETA lawsuit.

In 2009, one of the chimps born at Missouri Primate Foundation made national news. Connecticut couple Sandra and Jerome “Jerry” Herold purchased their chimp, Travis, from Casey for $50,000 when he was days old in 1995. Travis would sleep in bed with them, learned how to ride a bike, and was treated to steak and lobster tails at restaurants.

Then on Feb. 16, 2009, Travis snapped, horrifically attacking Herold’s longtime friend Charla Nash, ripping Nash’s nose, eyelids, lips, and hands from her body. The case made national news, and Casey attempted to paint the tragedy as an isolated incident. (“The Travis situation was a very unusual and horrible thing to happen,” she told documentarian Louis Theroux in 2011.)

But to Jason Coats, it wasn’t a one-off. He tells Rolling Stone how he felt forced to defend himself in 2001 when he shot and fatally wounded Travis’ mother, Suzy, who had escaped from Casey’s compound along with two other chimps.

Coats claimed Suzy was beginning to charge toward him when he shot the chimp three times. Although Coats and his friends testified in court that the chimps were out of control, Casey gave a drastically different version of events, claiming Suzy had been sitting peacefully.

Coats was arrested and later found guilty of animal abuse and property damage, and was a registered felon for 20 years. (His record was expunged only last year.) Coats believes that had the incident happened today, he wouldn’t have gone to jail, and has since become proactive in advocating against the private ownership of chimps. “There’s no reason that any of these animals should be anywhere near a residential area or a home with children,” he says.

Courtesy of Save the Chimps

Casey was in the thick of her lawsuit with PETA when Haddix arrived, hoping to buy a baby chimp from her. Befriending the elderly woman, Haddix says she thought she could help Casey wriggle out of the lawsuit by simply taking her chimpanzees off her hands. Moving into a mobile home on Casey’s compound, Haddix and Casey declared in court documents that Haddix became the legal owner of the chimps and took over their care in late 2018.

PETA argued that nothing had materially changed, with the living conditions at Casey’s facility remaining grossly inadequate for the chimps, as they added Haddix to the lawsuit.

After dozens of back-and-forth court filings, with subpoenas, declarations, and motions to compel discovery from Haddix, PETA and Haddix came to an agreement. According to a September 2020 consent decree, Haddix would give four chimps to the Center for Great Apes in Wauchula, Florida. In return, she would be allowed to keep three chimps, including Tonka. However, Haddix needed to overhaul the facility within six months, including installing or constructing an outdoor Primadome-structured enclosure for the apes. If she failed to comply with all stipulations of the decree, Haddix would have to turn over the three chimps to a sanctuary.

By January 2021, PETA alleged in court docs that Haddix had “defaulted on her obligations on four separate occasions” and had “evidence that indicates that the information she previously provided during her cure periods is, at least in part, false and fraudulent.”

In June 2021, after a judge found Haddix in contempt of court for violating the consent decree, he ordered all seven animals, including the three chimps Haddix was originally allowed to keep, to be sent to the Center for Great Apes.

A day after the judge’s order, Haddix began to claim to local news outlets that Tonka had died from heart failure on May 30. (In reality, she now says, she secreted Tonka away to a friend’s house, where he remained until fall 2021, when she moved him into her new home.)

When PETA’s attorney Jared Goodman emailed Haddix for more details about Tonka’s death, Haddix was curt. “I don’t appreciate you questioning my integrity,” she responded, according to court records. “You have repeatedly pushed and have insulted my morals. If you don’t like my answers or don’t feel I have done everything I can for these chimps, then you truly need to get your four awarded chimps and leave me [the] hell alone.”

In July, Haddix was forced to give up the six chimps, who were transported to the animal sanctuary, as PETA continued to push for specifics and proof of Tonka’s death.

Haddix ended up hiring attorney John Pierce, who represented Kenosha, Wisconsin, protest shooter Kyle Rittenhouse and several alleged Jan. 6 Capitol rioters. (Haddix fired Pierce in November. Pierce did not respond to a request for comment from Rolling Stone.)

“It was pure selfishness … [Haddix] denied Tonka not only the companionship of other chimpanzees, but she took him away from his family,” PETA’s Brittany Peet

In emails submitted as court evidence, Jerry Aswegan, Haddix’s husband, detailed how he allegedly disposed of Tonka’s body, claiming he had burned the chimp’s body for roughly four hours at 170 degrees. “Needless to say, it did the job,” he wrote. (In addition to Haddix, the judge has also referred Aswegan to the DA’s office for possible criminal perjury charges.) PETA called bullshit, claiming in court papers that the low temperature and short amount of time wouldn’t even properly roast a turkey. In another court filing, Aswegan countered it was simply a typo and he meant 1,700 degrees.

After several more attempts to get Haddix to produce adequate documentation and information about Tonka’s supposed death, Judge Catherine Perry issued an order last December that PETA needed to provide evidence that “Tonka is still living and/or that Haddix is otherwise in contempt of court.” The case was essentially at a stalemate. Trying to dig up information on Tonka’s whereabouts, PETA put out appeals for information and teamed up with Cumming. Finally, nearly a year after Haddix claimed Tonka died, PETA announced that it had received the recorded-phone-call tip, which led to Tonka’s discovery.

Even when officials arrived at her home, Haddix says, she was still figuring out how to keep Tonka, slipping out her back door to make some phone calls. Haddix says a marshal spotted her and confiscated her cellphone. “Trust me, I was trying to strategically plan on how I could get [Tonka] out of here,” she tells Rolling Stone. “I’ll be honest, if I could have got him out of here in between then, I would have because I would have got [him in a trailer], and I would’ve loaded him and we would have been gone.”

She also says she wasn’t above offering officials cash to turn a blind eye. “I said, ‘Please guys, I’ll give you $10,000 each. I’ve got plenty of cash in this house,’” she claims she told marshals. “I said, ‘I will give you a brick of $10,000 if you guys will just turn around and walk out and just tell them you did not find a chimpanzee here.’”

Whitney Curtis for Rolling Stone

Haddix is uncertain where things will go from here. Her first order of business is dealing with the prospect of jail time if Missouri’s Eastern District U.S. Attorney’s Office pursues criminal charges against her. But she has no regrets and her focus remains on Tonka. “I just know that I don’t want him to suffer at my expense,” she says.

This deep love of Tonka caused Haddix to struggle with her vet Casey Talbot’s advice to put him down because the chimp was allegedly in dire health conditions. (Haddix says the vet told her he was in congestive heart failure and had only weeks to live.)

“Tonka has been in bad health for quite some time,” Haddix alleges. “He had a massive stroke, he’s had congestive heart failure, he’s been on several medications, and basically has had vet care to evaluate him frequently.”

“And the last vet visit, the vet recommended that he be euthanized,” she claims.

But PETA offers a radically different assessment of Tonka’s health to Rolling Stone. After its own veterinarians did an assessment of Tonka after his rescue — which included blood work, an ultrasound, and an EKG — PETA says there was no suggestion that Tonka was suffering from congestive heart failure. (Peet has cast doubt on Talbot’s credentials for caring for primates, claiming to Rolling Stone that the vet mostly works with farm and domestic animals, and had no formal training on the medical care of primates. A representative for the medical program Talbot attended confirmed to Rolling Stone it does not offer any courses regarding the care of large primates.)

“While Tonka needs dental work and is substantially overweight, the examination did not show signs of congestive heart failure, which his former owner claimed he had for the last year,” Valerie A. Kirk, Save the Chimps’ director of veterinary services, says in a statement provided by PETA. “He shows no need for the heavy doses of medications that she was reportedly giving him or the euthanasia she was reportedly considering.”

Although Haddix told Rolling Stone multiple times that she would readily produce Tonka’s medical records or have her vet speak with Rolling Stone, the documents never materialized and the vet didn’t return a request for comment.

“I don’t think we’ll ever know what really happened, but the important thing is that Tonka is now safe, and we’re so excited to see what the rest of his life will bring,” Peet says. “I’m thankful that he finally has the chance to be peaceful. It’s tragic, but beautiful because that’s exactly what chimpanzees should have, is choice and control over their lives.”

Tonka now resides at the Save the Chimps sanctuary in Fort Pierce, Florida. (Haddix tells Rolling Stone it was the last place she wanted Tonka to end up, referencing a 2020 report that revealed the sanctuary had 12 Animal Welfare Act violations between 2015 and 2020, including three citations for medical care. After the report, Save the Chimps announced a change in “leadership and structure,” adding a human-resources director to the team.)

The 150-acre compound, which was founded in 1997, is the world’s largest privately funded chimp sanctuary, according to the nonprofit, with more than 200 chimps currently living on the grounds, divided into communities across a dozen three-acre islands. Like Tonka, his new neighbors have all come to the facility after being rescued from various research labs, the pet trade, and the entertainment industry.

With a relatively clean bill of health, Tonka can expect to live another 20 to 30 years, Peet says. There’s also a chance he could be reunited with his chimp family from the Missouri Primate Foundation — his partner, Tammy, as well as Candy, Crystal, Connor, Kerry, and Mikayla — at their sanctuary, if his adjustment period goes well and space opens up.

For now, the chimp is enjoying his time snacking on oranges and pomegranate seeds and swinging in his hammock, according to PETA and Save the Chimps. He has adapted well, greeting and excitedly interacting with other nearby chimps — something Haddix had claimed he would shun in favor of a preference for humans.

Most of his days are spent outside, with South Florida’s subtropical climate filling in for his natural habitat. When there are downpours, the other chimpanzees flee for cover. But Tonka stays put, letting the rain hit his skin.

Best of Rolling Stone