'The Sopranos' at 20: How David Chase's mob series revolutionized television

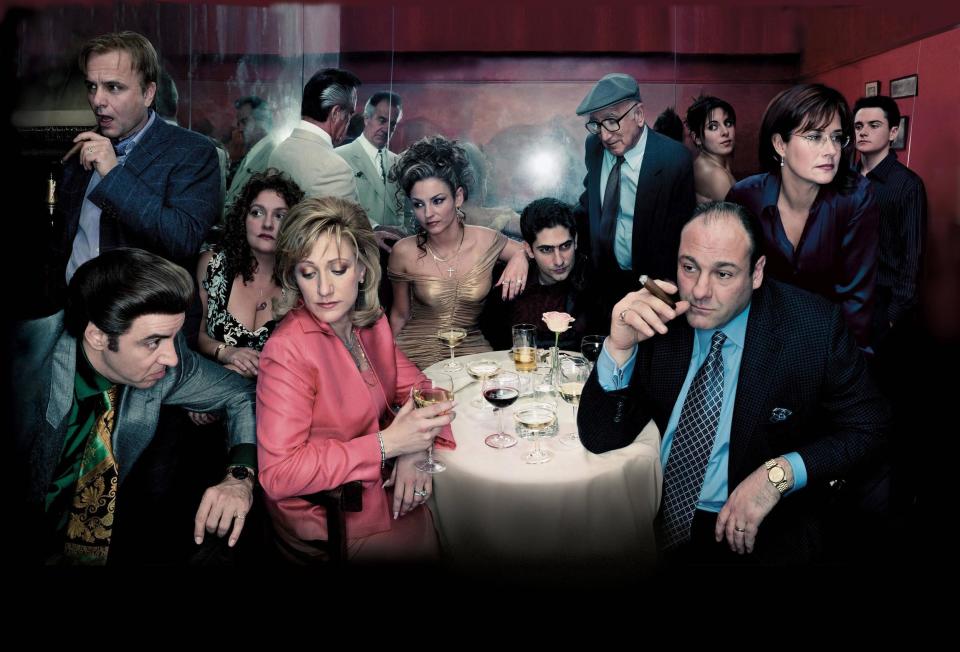

Twenty years ago, The Sopranos made the airwaves safe for antiheroes and auteurist television, and also paved the way for our current #PeakTV era. If you’re a fan of The Shield, Battlestar Galactica, Breaking Bad or Game of Thrones, you owe the show’s creator, David Chase, a debt of gratitude. But we’ve been living in a post-Sopranos world for so long, it’s sometimes difficult to remember what TV looked like before New Jersey’s most famous fictional mob family — Tony, Carmela, Meadow and A.J., played respectively by James Gandolfini, Edie Falco, Jamie-Lynn Sigler and Robert Iler — entered our lives on Jan. 10, 1999. To show how The Sopranos changed television as we know it, let’s turn the dial back to a period when TV sets had dials. (Watch our video history above.)

Once upon a time, episodic television followed a simple formula: The characters at the center of any given show were fundamentally good people forced to confront conflicts that could be resolved over the course of a half-hour or an hour. Depending on the genre, those conflicts ranged from the annoying family members among the Brady or Tanner clans to the lawbreakers that bedeviled generations of TV cowboys and cops, to the troublemaking aliens on Star Trek and The X-Files. Week in and week out, the heroes of these shows would be tested, but they’d never fundamentally change.

The 1990s did bring a few shows that put this traditional formula to the test. David Lynch’s groundbreaking cult series Twin Peaks introduced dream logic into mainstream television — something that The Sopranos picked up on for its own memorable dream sequences. Steven Bochco’s NYPD Blue took a grittier approach to the classic police procedural, with morally compromised cops spouting salty language and occasionally baring their butts. Fox’s brilliant, but short-lived corporate satire Profit featured an out-and-out villain (Adrian Pasdar) as its leading man. And two years before The Sopranos, HBO launched the late, great prison drama Oz, which took place in a maximum security jail where good men were hard to find. (Fun fact: The first two seasons of Oz featured the future Carmela Soprano in a supporting role.)

Despite those precedents, the shows that premiered in the fall of 1998 — including The King of Queens, L.A. Doctors and Providence — mostly followed the old model of TV storytelling. Then 10 days into the new year, the Sunday night premiere of The Sopranos ushered in a new kind of television. Funnily enough, Chase originally conceived of The Sopranos as a feature film, before using the mobster-in-therapy premise as the jumping-off point for a TV show. After being turned down by multiple networks, he got the go-ahead to make a pilot for HBO in 1997. The rest of the first season wasn’t filmed until a year later, which is why the cast — particularly Gandolfini — appear noticeably different between the first and second episodes.

Rewatching The Sopranos premiere today, it’s striking how confidently it breaks all of TV’s established rules. Chase dug deep into his personal life for material; growing up in an Italian-American enclave in New Jersey, he populated The Sopranos with the people — and pop culture — that defined his formative years. Plenty of TV creators have used their own lives for dramatic fodder. What set The Sopranos apart was the brutally honest way that Chase translated the flaws of the people he knew into the characters he created. That includes his own mother, who serves as the model for Tony Soprano’s bitter, vengeful mom, Livia, played by Nancy Marchand, who passed away during the show’s second season.

On the DVD commentary track that accompanies the pilot, Chase highlights both the positive and negative effects of psychotherapy, noting that it’s helped millions of people — himself included — but also that it can become a societal crutch. “I do believe that there’s a lot of excusing of bad behavior,” he notes. “America has become a psychiatric-oriented society — victim stuff and crying.” The Sopranos puts the audience in the uncomfortable position of having to watch its characters behave badly without any excuses or even immediate consequences.

Within the first 10 minutes of the first episode, we see Tony commit his first act of violence, chasing down and then beating up a gambler who owes him money. Later on, his nephew Christopher (Michael Imperioli) scores his first series kill by brutally executing a Czech mobster. And the pilot climaxes with Tony’s crew blowing up the restaurant of childhood pal Artie Bucco (John Ventimiglia) … although they believe that last criminal act is for a good cause, as it prevents a planned mob hit from sullying Bucco’s business.

Before The Sopranos, movies like The Godfather and Goodfellas mythologized Mafia life, and Tony and his associates like to imagine themselves as continuing that romantic tradition of the noble gangster — hence their plan to “protect” Artie’s restaurant. The pilot episode even imitates the visual style of The Godfather at times as a way to indulge the audience’s nostalgia. But Chase isn’t about to indulge the audience’s innate desire to sympathize with our main character. As played by Gandolfini, Tony is an alternately gregarious and terrifying figure.

On the commentary track, Chase points to a scene at the end of the pilot in which his star’s performance crystalizes who Tony is. In the scene, Tony confronts Christopher after the younger man casually suggests that he wants to use his life as the basis for a movie. Watching Gandolfini play that scene, Chase was struck by the way the actor could “turn on a dime from concern to rage, to really scary rage.” The rest of Tony’s family are also deeply flawed: Carmela is prideful, Meadow is spoiled and A.J. is directionless. Where television previously emphasized an idealized version of the American nuclear family, The Sopranos found its richest material in family dysfunction.

You can see the reflection of Tony and Carmela in TV marriages like Walter and Skyler White, Philip and Elizabeth Jennings and Don and Betty Draper. Those shows understand the power in exploring, rather than ignoring, the darker complexities of human nature. Not coincidentally, Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner was a writer on The Sopranos and brought the same level of exacting specificity to his own series. Chase emboldened an entire generation of TV creators to make visual artistry a feature — not a bug — of their storytelling. That impetus has resulted in such memorable moments as Battlestar Galactica’s elegant time jump to one of The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel‘s epic long takes.

Right up until the very end, The Sopranos defied television conventions. The 2007 series finale famously ended in Holsten’s diner, where Tony may or may not be killed over a plate of onion rings. Instead of revealing his ultimate fate, Chase opted for a sharp cut to black that led some to believe their TV service had been disrupted. Often lost in the ongoing debate over whether Tony is alive or dead is the fact that Chase provided an answer, of sorts, in the pilot. In their very first conversation, Tony tells his therapist, Dr. Jennifer Melfi (Lorraine Bracco), “Lately, I’m getting the feeling that I came in at the end. The best is over.” He’s referring to American society, but really, he’s talking about his own life. Tony is at his most powerful before the series begins; everything that happens after is a slow-motion crisis that chips away at the existence he’s constructed for himself and his family. There is no happy ending waiting for him — just more uncertainty.

Gandolfini’s own death in 2013 means that the diner scene will forever be our last glimpse of the adult Tony Soprano, though Chase plans to flash back to his younger days in a planned prequel film, The Many Saints of Newark. But the true legacy of The Sopranos lives on in the television we binge now. As long as Tony Soprano is television’s patron saint, we won’t stop believing in the creative power of Peak TV.

The Sopranos is streaming on HBO Go.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment: