‘The Sopranos’ Turns 25: How David Chase’s Series Changed the TV Rules

In the most important scene of the first season of The Sopranos — arguably the most important scene of television of the last 25 years, if not much longer — Mob boss Tony Soprano stalks and murders Febby Petrulio, a former wiseguy who testified against friends of Tony’s and then went into hiding.

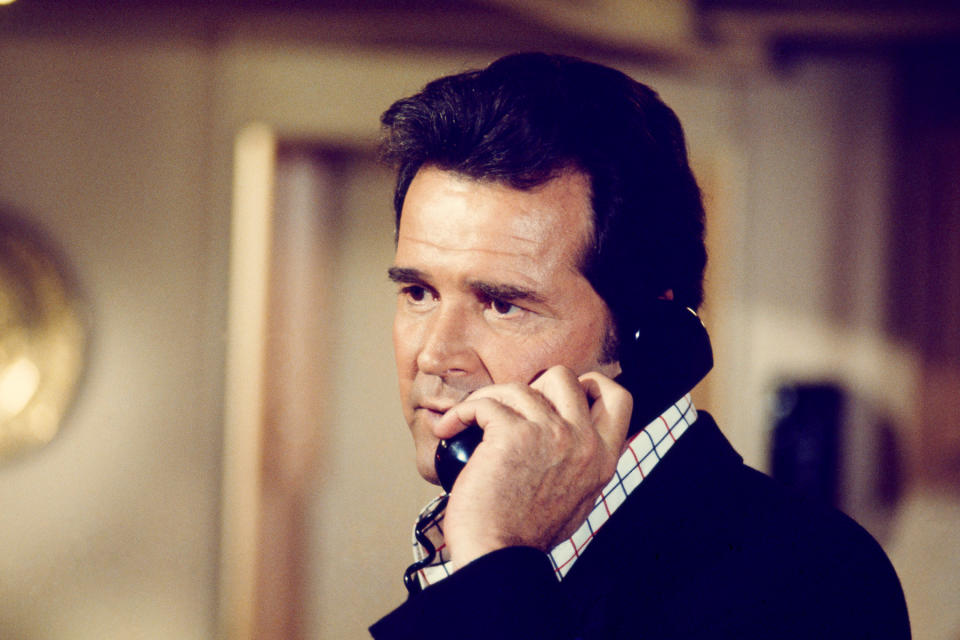

What would have happened, I asked Sopranos creator David Chase recently, if he had pitched the same idea 25 years before that, back when he was a young writer on The Rockford Files, a hit NBC drama starring James Garner as a wisecracking private detective? Jim Rockford had done time in prison, after all; maybe there was a fellow who wronged him badly enough to deserve being garrotted with piano wire? How, I wondered, would the executives at NBC in the mid-Seventies have reacted?

More from Rolling Stone

Here's Where to Stream Golden Globe Award-Winning 'Oppenheimer' Online

HBO Max Is Now 'Max' - Here Are Two Ways to Get the Streaming Service for Free

“Well, they would say, ‘You’re joking,’” Chase suggested. “And if we said no, we weren’t joking, then they would say, ‘Clearly we can’t do that, and certainly Garner isn’t going to want to do that. And when you walk out that door, you’re fired. You need psychiatric help.’ And they would mean it.”

The Rockford Files wasn’t that kind of show, and the world of television in 1974 has so little resemblance to the one that birthed The Sopranos — let alone to how TV looks today thanks to Chase’s work — as to practically be a different medium.

On January 19, it will be 25 years since The Sopranos debuted. A lot of people have said over the last quarter century that the series fundamentally changed television. This is such a big statement that it can be hard to get across exactly what that means. So for this silver anniversary, let’s try it a new way, with Chase himself talking about what life was like for him as a TV writer in the decades leading up to his masterpiece, and how different that job wound up being; and then with creators of four 21st century series that got to be born into the world The Sopranos recreated.

IN THE BEGINNING, THERE WAS REGULAR TELEVISION. AND IT WAS OK.

Rockford was a great job for Chase. Its co-creator, Stephen J. Cannell, was the Seventies equivalent of a prestige TV producer today. It had an all-time TV star in Garner. And it was considered the best of that decade’s wave of detective dramas, even winning the drama series Emmy in 1978. And Cannell, Chase, and their colleagues also understood exactly what was expected of them, and what wasn’t. Even if Chase had the Febby idea in the mid-Seventies, he would never have wasted time mentioning it in the writers room, let alone telling NBC about it. The goal was to make television that was easy to follow, featuring likable characters. You could do that at a very high level, as the Rockford team often did, but it wasn’t usually meant to be art.

There were, of course, exceptions in every era, like The Defenders, The Singing Detective, Hill Street Blues, or Twin Peaks, among others. But that was for the most part how television had operated for decades before, and would for decades after. In the mid-Nineties, Shawn Ryan was a writer on Nash Bridges, a popular, amiable CBS cop show starring Don Johnson and Cheech Marin. “There was a real emphasis on quantity: ‘How much can we make?’” he recalls. “We filmed Nash Bridges in seven business days. So there was a bit of an assembly line aspect.” There was room to tinker with the formula, but not much. “You were trying to do things that felt different, but also felt the same? That it’s in the realm of what the show is, but it’s a slightly different situation.”

And, of course, there were the network notes. Every broadcaster has its own censor department — referred to euphemistically as “broadcast standards and practices” — concerned about what characters could do or say, and what the audience should be allowed to see.

“We got tons of broadcast standards notes [on Rockford], all the time,” says Chase. “It was very cute, because our broadcast standards guy wrote porno. We had to put up with him.”

Still, Chase was lucky, and continued to get to swim in the deeper end of the network swimming pool. In the early Nineties, he worked on a pair of acclaimed Emmy winners: CBS’ quirky small-town Alaska saga Northern Exposure, and I’ll Fly Away, an NBC drama set in the Deep South during the civil rights movement. The experience on the latter in particular helped sour him on a medium he had once loved.

“I didn’t hate television,” he insists. “As a younger person, I watched a lot of TV. As I got to work in it, I hated the meetings. The meetings were awful. What they wanted from the whole thing, what they expected was just disgusting.”

With I’ll Fly Away, Chase and the show’s creators wanted to focus on the civil rights stories, and how awful it was to be Black in that part of the world at that moment in time. NBC executives, though, preferred the series’ warmer, more nostalgic side, particularly scenes where a Black housekeeper was tender with the white children she was taking care of.

“NBC put promos on the air with Louis Armstrong’s ‘What a Wonderful World,’” Chase recalls, still incredulous. “Really? For a Black woman in 1963, in an unnamed Alabama, ‘What a Wonderful World?’ What the fuck are you talking about?!”

“[Network TV] was like writing with handcuffs on,” agrees Terence Winter, who spent the mid-late Nineties writing for gentle comedies and family shows, before joining The Sopranos staff for the second season. ”You couldn’t really tell the stories that felt real. Everything was put through a filter of inoffensiveness, and dumbing down.”

“Those network executives had a knack,” says Chase. “They would cook the vitamins out of anything. By the time you got the string beans, they were flabby, overcooked, tasteless, with no salt. They always cooked the vitamins — and got you to participate in that. And they had flawless instincts for taking out the very thing that made the story worth doing. Whether it was right there right out front, or whether it was oblique. They always knew that, whatever you loved, they weren’t doing it for that reason. They would go after what a writer was excited about. So in I’ll Fly Away, for example, as writers, we were excited about these sociopolitical stories. But they liked, ‘Poor kid and his crazy mother.’ I think they were afraid of that show, also, because of the racial thing. But they bought it and put it on the air in the first place.”

Chase had tried leaving the TV business before, but kept taking jobs, even though his expectations for them were low. “Television is a machine!” he says. “It’s a box. Anything great could come over it, but nothing was coming over it that was any good.”

IT’S NOT TV. IT’S THE SOPRANOS ON HBO.

The idea for The Sopranos began as a potential movie script, because Chase still wanted out of TV and into film. Eventually, though, he found himself pitching it to the same broadcast network executives whom he blamed for cooking the vitamins out of things. At a meeting with CBS, he says then-network boss Leslie Moonves told him, “‘Look, I got no problem with the scamming, the robbing, the murder. But does he have to be depressed and go to a shrink?’” Fox executives claimed to be thrilled with the project, then ghosted him for months; finally, a mid-level exec called him to say, “‘I wanted to tell you, as a human being, that I really liked the script.’ Which basically meant ‘goodbye.’ But I always loved, ‘as a human being.’”

Over the course of trying and failing to sell a very un-broadcast show to broadcasters, a new path opened up: HBO was starting to make its own scripted drama series. And because the pay cable channel didn’t have advertisers, and because it was still so new in that area (only the prison drama Oz preceded Sopranos), executives there largely let Chase do what he wanted. When he had talked about the series elsewhere, industry veterans kept telling him that he would have to shoot the majority of it in Los Angeles, with brief trips to New Jersey each season to film some exterior scenes to create the illusion that everything was happening in the Garden State. Chase knew he had found the right home when, unprompted, HBO’s Chris Albrecht pointed to an early New Jersey reference in the script and asked, “‘Now, you’re really going to shoot there, right?’”

Chase had initially dreamed that HBO wouldn’t order The Sopranos to series, which might allow him to film a second hour on his own and take it to the Cannes Film Festival as a movie. But it turned out the TV business felt a lot less disgusting when he got to tell the kinds of stories he wanted to.

“I had the best job in Hollywood,” he says. “I had complete creative freedom. That’s why it was so good, if you want to say the show was good. Because they left us to our instincts.”

That reflected in the product immediately. “The day I saw the pilot of The Sopranos,” Terence Winter says, “I was practically trembling. It was so good, I couldn’t believe it. I don’t think I’d even finished finished watching it when I called my agent and said, ‘You’ve got to get me on the show.’”

Courtney Kemp, who would go on to create the Power crime franchise for Starz, was in grad school at the time. “I remember watching the pilot with my parents, and seeing [Tony and Christopher] beat the shit out of that dude. I was just thinking, YES! This is fucking awesome! To see somebody who didn’t have to be good.”

Over the course of making 86 episodes, Chase insists there were only two serious arguments with HBO: one about the title, the other about Tony murdering Febby Petrulio. The latter was a line TV shows weren’t supposed to cross, even in the Wild West of turn of the century pay cable. On the rare occasion when a protagonist killed someone in a situation where it wasn’t self-defense, the dead character was inevitably presented as a monster the world was better off without. Febby, on the other hand, was just some schmuck who supplemented his income from a travel agency by acting as a small-time drug dealer on the side. For Tony to strangle this guy in cold blood, entirely to make himself feel good, was shocking. That viewers not only accepted it, but grew to like the series more and more as it went on, all but set a torch to the unofficial rulebook that Chase, Ryan, Winter, and all their predecessors had to go by for the whole history of television up to that point.

Lee Sung Jin, who would go on to create this year’s acclaimed Netflix road rage satire Beef, was still in high school when Sopranos debuted, and didn’t get to watch it until after he finished college. As a serious television fan, he was blown away.

“I did not know television could be like that,” he says. “Sopranos just had it all, in a way that I don’t think a show blended so many different genres before. It’s technically this Mob show, but it was so funny, so dark, but very existential. It really made you reflect on the state of America, quite often. And these poignant themes of marriage, and family. It was like modern Shakespeare to me. I just found myself quoting lines all the time. And at the end of every season, you’re left trying to unpack everything you watched. They left so many things open [to interpretation]. I think we all as writers now try to copy that a lot of, like, Oh, it’s artistic to leave things for people to be thinking about and talking about well after the season is done.”

For Chase, all this freedom “was not a mental adjustment. I was a fish in water. It was so, so exciting — so artistically stimulating, creative, and fun.”

Early in his tenure at the show, Terence Winter was overflowing with pride when Chase asked him to get on a notes call with HBO and write down the concerns of the HBO executives. “I was like, Oh, this is great! It’s a big responsibility he’s trusting me with.” Winter dutifully wrote everything down, hung up the phone, and handed the paper to Chase — who promptly wadded it up into a ball and threw it in the trash, unread. “I thought, That’s how you take notes!”

In general, though, Chase got along famously with his new bosses. He and HBO executive Carolyn Strauss would have spirited disagreements from time to time — most notably regarding the show’s divisive ending — but, ”It was two people actually talking to each other.” And he tended to get his way. He wanted to send Tony’s wife Carmela to Paris for an episode in the sixth season, so she could be confronted with the notion that the world she thinks is everything is in fact so insignificant to the wider planet; HBO was wary of the expense, but agreed. Chase did elaborate dream sequences. He let some stories end anticlimactically because he didn’t want the audience to feel like they could predict what was coming. And he could trust his remarkable ensemble — the late, great, James Gandolfini most of all — to say a lot more with their faces than with dialogue. In one of his favorite scenes, Tony has an emotional breakdown while in the car listening to the song “Oh, Girl” by The Chi-Lites, and it’s left entirely to Gandolfini’s expressions to get across the complicated, at times conflicting, feelings he’s struggling with as the song continues.

How much of the show’s success, Chase asks rhetorically, was due to Gandolfini? “A lot. It’s not too easy to talk about, because it’s all about the emotion [of missing him]. But it’s a tremendous amount. There would have been no show. We wouldn’t be talking today. Another actor, that [scene] would not have gone so deep into your heart, or your brain, or your chest, or whatever. That says it all. And I believe he was sometimes smiling during that. Smiling lovingly while he was crying, or laughing at himself. I don’t know. It’s just too much to even quantify.”

TONY SOPRANO’S MANY CHILDREN

Sopranos obsessiveness quickly swept through the TV business. “When [future Mad Men creator] Matt Weiner got on the show,” Winter recalls, “he said, ‘This is just like my old job. We talk about The Sopranos all day.”

Shawn Ryan was so inspired by the Febby episode that he wrote a Sopranos spec script, where Christopher pulls off a robbery, then has to wrestle with the fact that an innocent civilian died in the process. Then he went even further through the door Chase had opened, writing the script that became The Shield, a gritty drama starring Michael Chiklis as Vic Mackey, an unrepentantly corrupt LAPD detective. At the end of the first episode, Vic murders another cop in cold blood — a decision even more startling in some ways than the Febby one, because at least Tony was a mobster, whereas TV had always presented police officers with reverence in the past.

“I viewed it as an opportunity,” Ryan says. “I had spent nine years trying to be a TV writer. And suddenly, I was being told that being a TV writer could mean more than I had been led to believe. When I started, there was a real stigma: ‘TV writer is a lesser form than film writing. Movies are the ultimate goal, and TV is what you do when you can’t do movies.’ The Sopranos, to me, was the very first thing that started to largely challenge that narrative. I would not have written that script if The Sopranos was not on the air.”

The Shield put previously obscure basic cable channel FX on the map, and in the process started an avalanche of darker, more complex new series that completely altered the face of the TV landscape. Ideas that had once seemed impossible — the pitches Chase never would have bothered with on Rockford Files — were now inspiring bidding wars. Tony Soprano led to Vic Mackey, who led to Don Draper and Breaking Bad antihero Walter White, and to so many more. As a key Sopranos writer, Terence Winter was able to get the wildly expensive period Mob drama Boardwalk Empire on the air a few years after his old show cut to black. (Though as he notes, having Martin Scorsese directing the first episode helped as much as the Sopranos pedigree.) And as each new outlet got into this prestige drama game, the rules kept being rewritten on the fly, in a way that could feel overwhelming even to the people making the shows.

Ryan enjoyed asking his Shield writers, “‘What haven’t we seen on TV before, and how can we do it?’ It was incredibly liberating, but it was also terrifying, because we were always wondering, Is this the episode where we’re going to cross the line and repulse everybody? Frankly, I got put in this unfortunate position where all the writers working for me were coming up with outrageous stuff — you can just imagine the stuff [future Sons of Anarchy creator] Kurt Sutter was pitching — and I had to figure out where the lines were, and what the audience would be OK with.”

There were other limitations to this big change. Most of the early Sopranos descendants were also about aggrieved middle-aged white men; it wouldn’t be until the mid-late 2010s when characters from very different backgrounds, and in different kinds of stories, got to regularly exist in this same creative space.

When Kemp was developing the first Power series — about a drug dealer trying to go legit — ”We used to joke about calling it The Blapranos. I feel like Black audiences, audiences of color, they deserve prestige TV. Why can’t they have it? I definitely felt like, There’s a lot of middle aged white guys who are fucked up. Thank you very much. This is great. But the condition of being a Black man in America, that condition of being told you’re a man, but being told you’re a second-class citizen, is an interesting condition to unpack from a perspective of someone who is not the image that we see every day.”

Beef is about a specifically Asian-American experience, yet when Lee Sung Jin put together a writing staff, among the first things he did was to give everyone copies of the book The Sopranos Sessions(*), because, “I jokingly said that the Beef tone is 35% Sopranos comedy, laughing at the broken psychology of characters, plus 35% White Lotus, propulsion and water cooler moments, plus 30% Ingmar Bergman warm melancholic pathos. So in order to even begin that formula, you have to really understand why Sopranos is funny.”

(*) Co-written by [checks notes] me.

Beef is far from the first 21st century comedy with clear Sopranos DNA, as the public’s fascination with Tony made it easier for TV shows in multiple genres to revolve around less-than-wholesome protagonists. (Though, to be fair, Seinfeld and Curb Your Enthusiasm played a big role in this, too.) “I think Sopranos had to come along and allow studio executives to feel comfortable that it is OK to watch people be horrible,” says Lee, who wrote for several comedies in this vein, notably It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia. “Before Sopranos, what was edgy, and what was funny, the bar was so different.”

“I was always interested in people who could get away with shit,” says Kemp, who before Power wrote for broadcast dramas like The Good Wife. “There is obviously a change from just watching the good guys. My character Ghost, in the first four pages of Power, he’s murdering somebody. I remember distinctly when I pitched it, Marta Fernandez, who was an executive at Starz, she said to me, ‘Well, the problem with you broadcast writers is you like to pull your punches.’ And I was like, ‘Wait a minute, bitch, I will not pull my punch.’ But, of course, The Sopranos opened the door for that.”

It would be wildly reductive to suggest that the only impact Sopranos had on the medium was to make it easier to build shows around killers and other disreputable types. Though few who followed Chase received the total creative freedom he was given, it was nonetheless clear to the industry that if you let people make projects they were passionate about, and if you gave them a wider degree of latitude than was previously the norm(*), they might make something that the audience was passionate about, too. Assembly line product continued to be churned out, but was now being made in parallel to idiosyncratic shows with distinctive voices. Superficially, for instance, Atlanta has very little in common with Sopranos, but Donald Glover has talked about how growing up watching Tony and friends was a major influence on the kind of TV he’s made himself. You can’t trace every great 21st century show’s DNA back to North Caldwell, NJ, but you can trace an awful lot of it.

(*) Again, great television predated Sopranos, and often benefited from similar circumstances. Norman Lear got to make All in the Family the way he wanted to because CBS in the early Seventies was so eager to shed its image as the home of Petticoat Junction and other silly rural comedies. Rod Serling made The Twilight Zone at a time when television was so new, the rulebook wasn’t entirely codified yet. Etc.

“It really was a paradigm shift in terms of what was possible on TV,” says Ryan. “I think it is safe to say that if David Chase hadn’t done The Sopranos, I think the television landscape would have been very different.”

“I think everything that has come after Sopranos owes a lot to David Chase and those writers,” adds Lee. “Every major show that has been an award contender, that is trying to go for art in the television medium, wouldn’t be able to exist. I think it is the most influential show of the modern era.”

There’s been some retrenchment over the last few years, as the sheer amount of television being made — much of it in this expensive, morally ambiguous space — has turned out to be unsustainable.

“Sopranos showed the world what you can do on TV and in a series,” Winter argues, “but I don’t know that it’s gonna last.”

Chase hasn’t watched much post-Sopranos television himself, outside of Boardwalk Empire and Mad Men, due to his connection to their creators. So he doesn’t feel qualified to weigh in on how he feels his work changed the medium, nor how permanent those changes might be. But he does have thoughts on why the series resonated with so many, whether they were watching TV or making it.

“It’s difficult, because I don’t want to sound conceited,” he says, “but I was proud. On some level, it went back to when I was still working in network television. I got interested in this song, ‘Radio, Radio.’ I love Elvis Costello. The lyric was, ‘Some of my friends sit around in the evening and they worry about the times ahead. But everyone else is so overwhelmed by indifference and the promise of an early bed. It’s either shut up or get cut out. They don’t want to hear about it. It’s only inches on the reel-to-reel. But the radio is in the hands of such a lot of fools, tryin’ to anesthetize the way that you feel.’ And there’s another verse: ‘I want to bite the hand that feeds me. I want to bite the hand so badly. I want to make them wish they’d never seen me.’ And I believe I succeeded.”

Best of Rolling Stone