"On the Space Oddity album we had no idea what we were doing. So we tried something different, something harder": the making of David Bowie's The Man Who Sold The World

B y March 1970, Major Tom was becoming something of an albatross to his 23-year old earthly counterpart David Bowie. The success of his single Space Oddity, which reached No.5 in the UK and sold nearly 150,000 copies, had pushed up fees for Bowie’s live shows and made him flush for the first time in his six-year career. But the song’s connection to the Apollo Moon landing had coloured it with a novelty status that he was finding it difficult to get past. His latest single, The Prettiest Star, written for his new bride Angie and featuring Marc Bolan on lead guitar, sold only 800 copies and didn’t even make the charts.

Bowie had other troubles on his mind too. He was grieving for his father, who had died a few months earlier at the age of 56. His management contract with Ken Pitt had soured to the point where he wanted out. There was also the delicate matter of his schizophrenic half-brother Terry, who’d been living with his parents. After Bowie’s dad passed away, his mother, unable to cope with Terry, committed him to Cane Hill Asylum. Bowie visited him regularly, but felt increasingly guilty over not being able to do more to help.

Looking back in a 1971 Phonograph interview, Bowie summed up his state of mind at that time: “I really felt so depressed, so aimless, and this torrential feeling of: ‘What’s it all for anyway?’ A lot of it went through that period.”

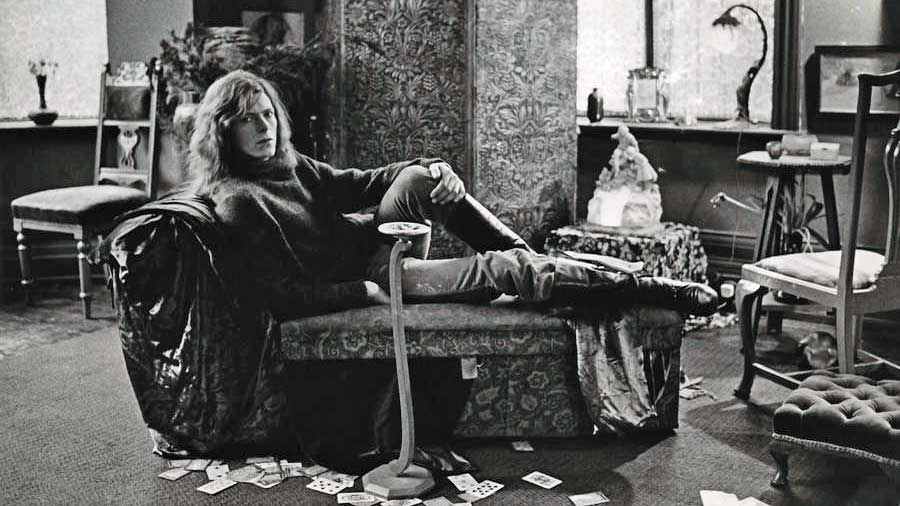

So it made sense to stay cocooned with Angie in their flat at Haddon Hall, a shambling old Victorian house in Beckenham. Sharing the rent was Bowie’s producer pal Tony Visconti, and his girlfriend. The record that became The Man Who Sold The World began with their late-night conversations about the idea of moving away from singles toward albums.

“We wanted to make an art-rock album,” Visconti said in Dylan Jones’s book David Bowie: A Life. “On the Space Oddity album we had no idea what we were doing. It was all over the map. So we tried something different, something harder. We just threw caution to the wind. It had to be seen by our peers as a work of art rather than just a pop album, as David and I were into the idea of a concept album. The single went out of favour for a while because the likes of Led Zeppelin and Yes were making albums that were outselling singles for the first time We wanted to be seen as a great album group.”

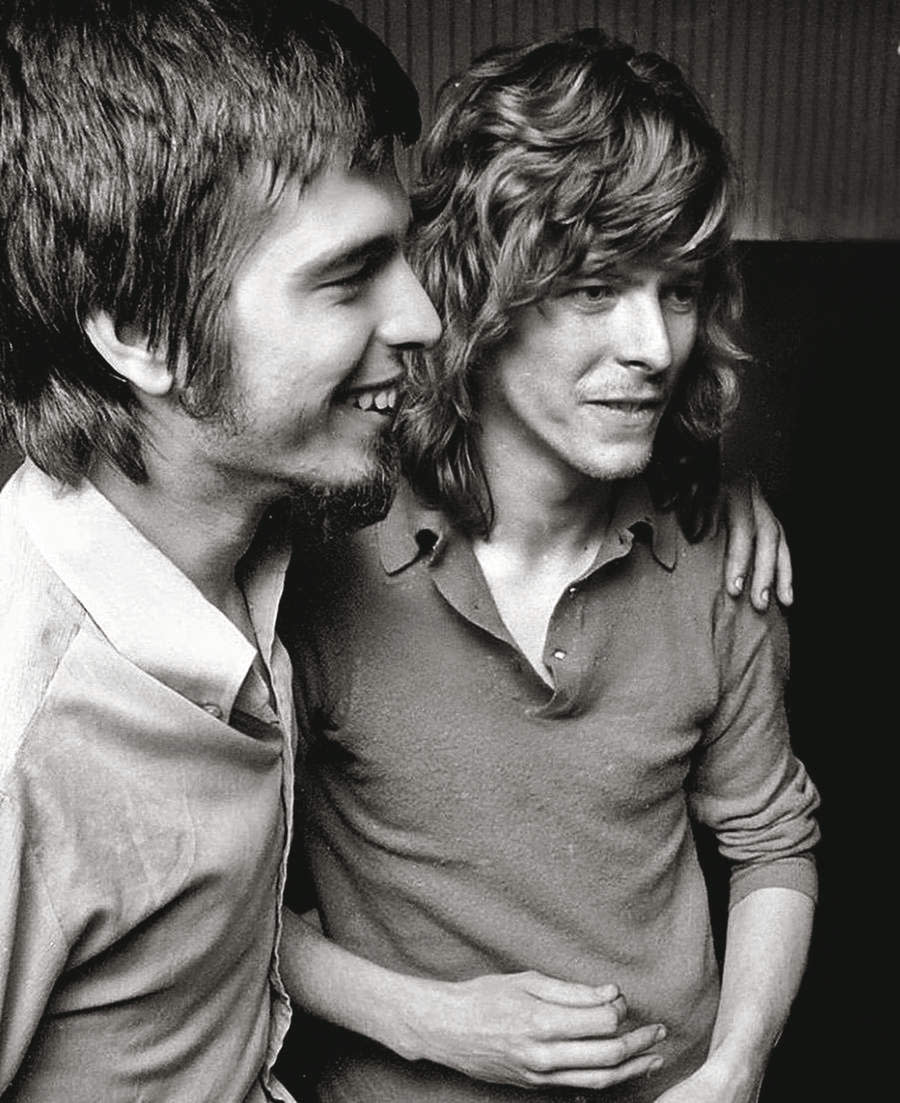

With Visconti on bass, Bowie’s new band began to come together that spring with the arrival of two musicians from Hull – guitarist Mick Ronson and drummer Woody Woodmansey. Ronson had met Visconti on a session for Michael Chapman’s album Fully Qualified Survivor, a now-forgotten record that, thanks to Ronson’s touch, has pre-echoes of Hunky Dory. Ronson attended a Bowie show and afterwards returned with him to Haddon Hall for a late night jam.

In Beside Bowie, the 2017 documentary about Ronson, Bowie recalled: “I started playing some of my songs on my twelve-string and he plugged in his Gibson. Even though he was playing at a very low volume, the energy and grit cut through the room and he immediately established himself as a very well-defined player.”

“Mick was like Jeff Beck, Eric Clapton and Jimi Hendrix all rolled up in one person,” Visconti told Performing Songwriter. “He had it all, and his technique was phenomenal, as were his sensibilities. He knew the right notes to play, the right way to play a song. Give him a song for ten minutes and he was there.”

That idea was tested two days later, when Ronson, with no rehearsal, did his first gig with Bowie, on the BBC In Concert series. “It was incredibly exciting,” Visconti said in David Bowie: The Golden Years. “Because we knew that Mick was going to work out – he had something we needed.”

With his enthusiastic demeanor and deep musical vocabulary, Ronson was a perfect foil for Bowie. After he moved into Haddon Hall, the two became inseparable, and would sit for hours across from each other, working out chord progressions and designing the riffs that would inspire the songs on The Man Who Sold The World.

Ronson also quickly became frustrated with Bowie’s then-drummer, John Chamberlain, and suggested a replacement. That replacement, Mick ‘Woody’ Woodmansey, recalled his first impression of Bowie as a musician who was being an artist 24/7: “Although he really hadn’t got it figured out at that time, I looked on him as an artist in preparation. He had all these ideas but he hadn’t really sorted out a direction. And he didn’t really know rock’n’roll music at that time. Which is where the band came in.”

The other major player who entered Bowie’s life that spring was Tony Defries. In April, Bowie had his fateful first meeting with the bushy-haired, cigar-smoking 26-year-old litigation clerk and would-be show business agent. His role model was Elvis’s manager Colonel Tom Parker, and Defries was convinced he’d found his Elvis. He seemed to intuit all Bowie’s career angst, and made big promises: he’d get Bowie out of his management contract with Ken Pitt; he’d get him onto a better label; he’d make him “bigger than everybody”. All Bowie had to do was be creative and write songs. He’d take care of the rest.

Three years later, Bowie told BBC Radio 1: “He said: ‘I’m going to make you a star!’ ‘Oh yeah?’ And he did… so they say. I’ve read about it. That’s when Tony Defries entered my life – and me wallet!”

Many legal battles loomed ahead, and it would be 1982 before Bowie would fully extract himself from the management contract with Defries that he said was “the worst decision of my life”.

Meanwhile, back at Haddon Hall in spring 1970, the new group started rehearsing in the wine cellar. Visconti said in The Golden Years: “We cleaned it up and put up eight crates on the wall as soundproofing. To this day I don’t think those crates ever worked. We got a lot of complaints from the neighbours, as we spent weeks down there. We made this album our job, and by the time we got into the studio we were very well-rehearsed. It was just a matter of putting all the tracks down and recording it.”

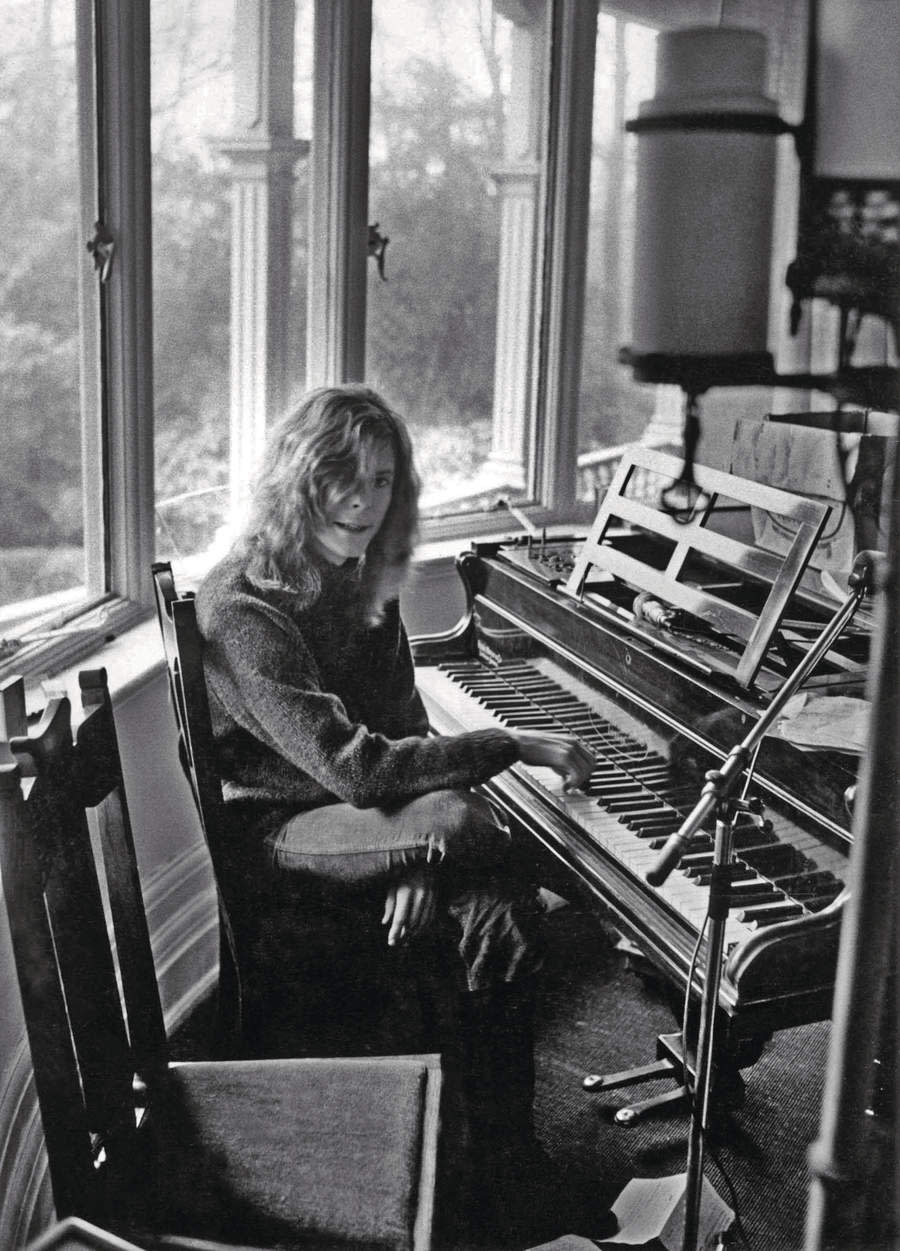

But upon entering the studio, Bowie was procrastinating about finishing melodies and lyrics for the instrumentals that the band were assembling. Visconti recalled: “Mick, Woody and myself would be making up backing tracks, having got a brief from David – it was an E chord for 16 bars, then an A chord for four bars – and we were just banging out these backing tracks, and David would come into the studio and say whether he liked it or not.”

Royal Academy-trained pianist Ralph Mace was brought in to play a Moog synthesiser. “It was creation in the studio,” Mace said in Peter and Leni Gillman’s Alias David Bowie. “They began with a basic idea from one instrument or one vocal line. They would start adding and would change according to their whims. David bounced ideas off people. There was a lot of creative interplay.”

But for all the collaboration, only Bowie’s name would appear on the songwriting credits. “It’s hard to say how much you do when you write a song with someone else,” Visconti said. “And even though we weren’t credited as writers, Mick and I were getting the chord changes together. The Width Of A Circle was the only track that was written, and that was only the first part of the song. The second part was written in the studio, and Mick and I definitely wrote all that, and David just threw all his words and melody on top.”

It’s not clear why Bowie didn’t assert control more. It could be that he wasn’t yet confident enough to assert himself, thinking it best to let the more experienced musicians run the show. Engineer Ken Scott, who would be in the producer’s chair for Bowie’s next three breakthrough albums, said in a YouTube interview: “Tony and Mick did take over. How much it was David not wanting to have anything to do with it, and how much was Tony taking over, I don’t know. But I think it was more Tony’s ideas on the album than David’s.”

Or it could have simply been that Bowie was formulating the working method that would give his coming decade of albums such spontaneity and character. On The Man Who Sold The World, the songs are almost more interesting for what they hint at than what they are: The Width Of A Circle, with its eight-minute ramble through tempo and mood shifts, is a precursor to Station To Station; She Shook Me Cold foreshadows Ziggy’s glam sexuality; Saviour Machine is a queasy dystopian preview of Diamond Dogs; All The Madmen and The Supermen move deep into the lyrical themes of alienation and loneliness that Bowie explored throughout his career.

For much of the album, the songs seem to wander away from the singer, turning into extended jams. Then suddenly, on the last two songs, everything snaps into focus.

It was the final day of mixing, and Bowie still hadn’t come up with words for the second-to-last track. With Visconti waiting impatiently at the console, Bowie hunkered down in the studio lobby and scratched out what became the title track and the best one on the album.

Bowie later referred to the song as “trance-like”, saying: “My state of mind when I was writing it was as near to a mystical state as a nineteen-year-old can get into. It was at a time when I was sort of studying Buddhism.”

Visconti referred to this as “writing on microphone”. He said in David Bowie: A Life: “David would start singing spontaneously. It was really wonderful. When he was hot, he was hot. But for me the whole thing was not so good. I had two big conflicts: getting this done technically, which I was struggling with, and also managing to get a good performance out of David. I had a record company screaming for final mixes, not even sure that they wanted this album. As far as they were concerned, this was the last they had to do with David Bowie and I wasn’t delivering the goods.”

The Man Who Sold The World was released on November 4, 1970 in the US, and April 10 the following year in the UK. Rolling Stone described it “intriguing and chilling”. Phonograph Record praised it for “trying to define some new province of modern music”.

In support of the album, Bowie did a brief tour of US college radio stations, showing up in his Mr. Fish dress, confounding and charming DJs. But since Olav Wyper, his champion at the label, had departed, Mercury did little to promote the record. By early 1971, Tony Defries was already busy engineering Bowie’s move to RCA Victor.

The pushy manager’s increasingly hands-on presence in Bowie’s life ended up forcing Visconti out of the picture and on towards his fruitful partnership with Marc Bolan and T.Rex.

“David was assigning his power to other people,” Visconti said in The Golden Years. “When he meets someone, and he falls in love, forget it. The person’s the one until he’s severely hurt. I said to David: ‘If you go with Tony Defries, I’m not going to go with you.’”

The album enjoyed a brief resurgence in 1974 after Lulu had a UK No.3 hit with her cover of the title track. Produced by Bowie and Mick Ronson, and featuring the Spiders From Mars as a backing band, it veered even further towards the Berlin cabaret feel that was hinted at in the original.

“I didn’t think The Man Who Sold The World was the best song for my voice, but it was such a strong song in itself,” Lulu told author Marc Spitz. “Bowie kept telling me to smoke more cigarettes, to give my voice a certain quality.”

In 2020, Tony Visconti returned to the original tapes of The Man Who Sold The World to create a 50th-anniversary stereo remix. To distinguish it from the usual remasters, it was given its intended title, Metrobolist, and used the sleeve illustration from the alternative US 1970 release. But even with the fresh take, The Man Who Sold The World still occupies a strange place in Bowie’s discography. Rarely listed as a favourite or in a top-five, it’s a preview of the conceptual, harmonically adventurous artist who would find much fuller flower on the two albums he would make just around the bend, and an entrance way to the unparalleled string of masterpieces to follow over the decade – from Aladdin Sane to Scary Monsters.

David Bowie once described his artistic vision to me as it bloomed in the early 1970s: “What my true style was is that I loved the idea of putting Little Richard with Jacques Brel, and the Velvet Underground backing them. What would that sound like? It really seemed that what I was good at doing and what I enjoyed was being able to hybridise these different kinds of music. As if to say: ‘Wow, this is no longer rock’n’roll. This is an art form. This is something really exciting!’”