The spectacular rise and tragic fall of Paul Kossoff

It was the air stewardess’ scream that told them something was very wrong. The ‘red-eye’ from Los Angeles to New York had just landed at JFK Airport. Until a few minutes ago, the blues-rock group Back Street Crawler and their crew had been asleep, scattered throughout the half-empty plane. Roused from a collective torpor, they blinked and stared as the stewardess ran down the aisle. “I looked at where Paul Kossoff had been sitting and the seat was empty,” says former tour manager John Taylor. “But the flight was only 30 per cent sold out, we’d all moved around, so I didn’t think anything of it.”

Before long, a group of NYPD officers had trooped on to the aircraft. By then, everybody knew the awful truth. The lifeless body of ex-Free, now Back Street Crawler guitarist Paul Kossoff had been discovered slumped in the bathroom. At some point during the flight, Kossoff had visited the toilet – and never come back. It was March 19 1976, and one of rock’s greatest guitar players was dead. He was just 25 years old.

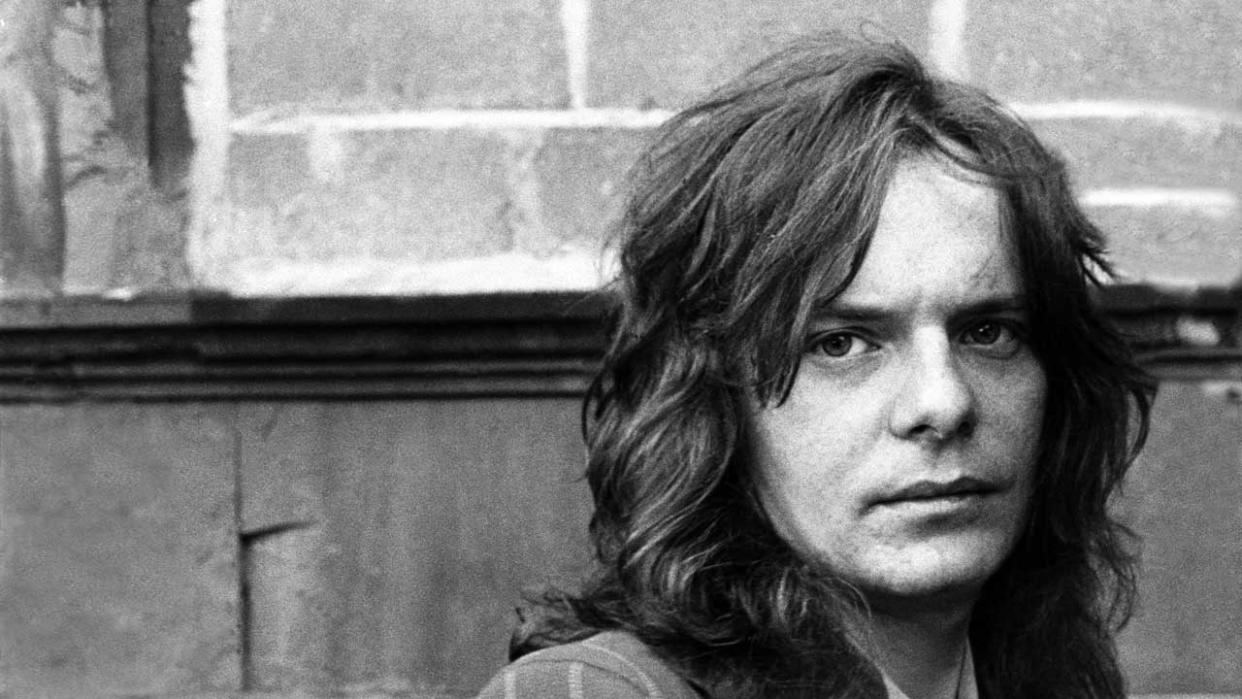

Forty years after his death, Kossoff’s music remains frozen in time. Albums such as Free’s Fire And Water and the hits Wishing Well and All Right Now have arguably grown better with age. From AC/DC to The Black Crowes, from Lynyrd Skynyrd to Rival Sons, each generation brings another group beholden to Free’s bare-boned approach. At the heart of their appeal is Paul Rodgers’ voice and Paul Kossoff’s spare, soulful guitar playing. Eric Clapton, Peter Green, Brian May and Joe Bonamassa are just some of those who’ve paid homage to Kossoff and his sound.

The story of Paul Francis Kossoff is a Shakespearean tragedy, with the guitarist as its gifted, damaged hero. Fame, money, drugs and some unresolvable inner torment all played a part in his downfall. Sadly, all the praise in the world couldn’t keep Paul Kossoff alive.

Paul was born on September 14, 1950 in Hampstead, north London, to parents David and Jennie. David Kossoff was the son of Russian-Jewish immigrants and a radio, film and TV actor. By the late 50s, he’d become a household name playing the Cockney patriarch Alf Larkin in the TV sitcom The Larkins. In the 60s, his popular radio show heard him reworking traditional Bible stories for a modern audience.

Growing up, their second son Paul showed a wit and precocity beyond his years. But he also had a taste for what his father called “dangerous pursuits… the risky rather than the peaceful”.

Paul attended his first concert, Tommy Steele at the London Palladium, aged eight. Shortly after, his parents brought him his first guitar, and enrolled him for classical guitar lessons. Paul struggled academically, but his strong, squat fingers made light work of forming shapes and chords. Before long, he was playing in a school group and upsetting the neighbours by rehearsing in the Kossoff’s garage.

Paul’s sometimes disruptive behaviour and poor academic record meant he was expelled from school, and gave up his education for good aged 15. Instead, he went on the road, as a trainee stage manager on one of his father’s touring productions. Then came the night in December 1965 when he saw Eric Clapton with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in concert. “I didn’t know who he was or what had gone down, but here’s all these people yelling, ‘God! God!’ He really caught my attention.”

Kossoff was soon hooked on Clapton, Peter Green and ‘the three Kings’ – Albert, Freddie and BB – and working in Selmer’s music shop on London’s Charing Cross Road. Here he served the then-unknown Jimi Hendrix and watched spellbound as Hendrix flipped a guitar upside down and played it left-handed. “I loved him to death,” he said, in a statement more prescient than anyone could have imagined.

Within a year, Kossoff had joined the north London blues group Black Cat Bones and impressed them with a confidence and stagecraft that belied his 5ft 3in stature. And in the meantime, 17-year-old Simon Kirke was a drummer in search of a gig. Kirke had grown up in Shropshire, but moved to London in 1965. He saw Black Cat Bones backing New Orleans pianist Champion Jack Dupree at a pub in south London, and joined them soon after.

Kirke wasn’t sure about the band, but loved the guitarist: “He was a little bloke with a mane of long hair.” What impressed him most was that Kossoff wasn’t trying to compete with lightning-fingered players such as Clapton. It was almost as much about the notes he didn’t play as the ones he did.

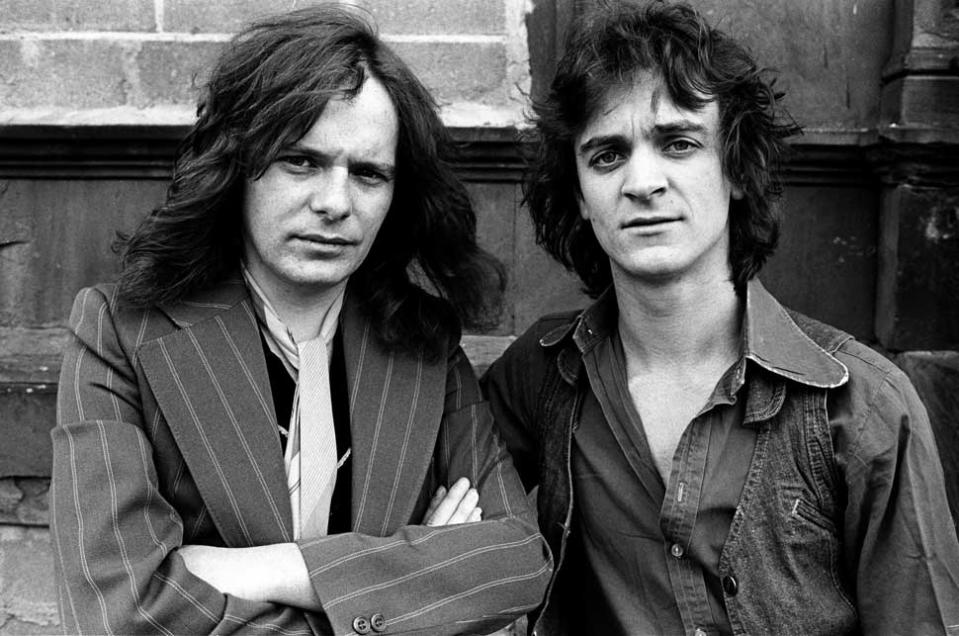

Shortly afterwards, another aspiring group, The Wildflowers, moved from their native Teeside and into a house near the Kossoffs in Golders Green. Their singer was Middlesbrough docker’s son Paul Rodgers. “Kossoff came round to the house,” recalls Rodgers now. “We jammed and I liked his style – both in his playing, his look and his humour.”

When The Wildflowers broke up, Rodgers remained in London and joined another group, Brown Sugar. Kossoff jammed with them at a blues club in Finsbury Park. “We did Stormy Monday Blues, Three O’Clock In The Morning by BB King – brought the place down,” said Rodgers. Kossoff asked Rodgers to join Black Cat Bones. But the singer refused: “I knew I wanted to start a new group instead.”

In 1968, every musician in Britain knew Alexis Korner. Earlier in the decade, Korner’s ensemble Blues Incorporated had beena valuable training ground for several future Rolling Stones. In March ’68, chief Bluesbreaker John Mayall told Korner he was looking for a new bass player to join the band. Korner suggested his daughter Sappho’s boyfriend, a 15-year-old, part-English, Barbadian and Guyanese musician named Andy Fraser.

Fraser lasted six weeks with Mayall before getting fired. But when Paul Kossoff told Korner he was looking for a bass guitarist, Korner knew just the boy.

The band that would soon become Free jammed together for the first time on April 19 1968 at the Nag’s Head in Battersea. Andy Fraser’s first impression of Kossoff was that he looked like a “little lion cub.”

The chemistry between the four was instantaneous. But within that was the rapport between Kossoff and Rodgers. “My playing was still very primitive at this time, but it had something in common with the way he sang,” said Kossoff.

“There was an instant spark,” concurred Rodgers. “He was as intense and emotional about the music as I was.”

Three days later, Black Cat Bones joined Champion Jack Dupree at CBS studios to play on his album, When You Feel The Feeling You Was Feeling. Paul Rodgers watched from the sidelines. Black Cat Bones knew what was coming. Their drummer and guitarist were moving on.

Soon after the Nag’s Head jam session, the new band were backing Alexis Korner in blues clubs around London and the Home Counties. Their name, ‘Free’, reflected the foursome’s stripped-down approach in the post-Sgt. Pepper era they found themselves in. “You must remember, in those days, it was all sort of arty-farty in Britain,” said Simon Kirke. “We were a blues band, so we decided on Free, which we thought was something a bit more nebulous.”

Korner recommended Free to Island Records’ boss Chris Blackwell. Island’s diverse roster included underground rock heroes Traffic and Spooky Tooth, and reggae acts Jimmy Cliff and Millie Small. In June, Blackwell saw Free opening for Albert King at the Marquee and was impressed. Shortly after, he sent Island’s management team to watch them showcase in a club in London’s Leicester Square.

“It was in a room not much bigger than my lounge,” says Free’s ex-manager John Glover now. “Paul Rodgers was about three feet from my face. It was very full-on and I found it a bit aggressive.”

Glover told Blackwell he wasn’t convinced. The following day he was called into Blackwell’s office. “And there were the four of Free sat on the sofa. Chris said, ‘This is John. He didn’t like what he saw yesterday, but he is going to be the guy looking after you.’ It was not the best start.”

Although he’d just turned 16, Andy Fraser had appointed himself Free’s leader at their first meeting. “Andy made all the decisions,” confirms Glover. “But Paul Rodgers also wanted to make decisions. Those two pretty much ran the band.” In contrast, Simon Kirke “didn’t say a lot unless he was upset about something”, and Paul Kossoff was “very, very gentle”.

In Glover’s opinion, “music was Koss’ life.” The rest of it – the business and the band politics – was an unwelcome distraction. And he certainly wasn’t a drug casualty. As the only one with a licence, Kossoff drove the band’s Transit, clocking up hundreds of miles week after week. “You have to be together to do that,” insists Rodgers. “Paul was a very together guy, a soulful, intelligent guy.” Off stage, he was quick-witted, a sharp mimic and, many believe, could have been a good actor.

He was also, already, an in-demand guitarist. Earlier that summer, blues producer Mike Vernon asked Kossoff to play on New York singer Martha Veléz’s debut album, Fiends And Angels. Kossoff’s understated solo on the song Swamp Man trailered the sound of Free’s debut album that was recorded soon afterwards.

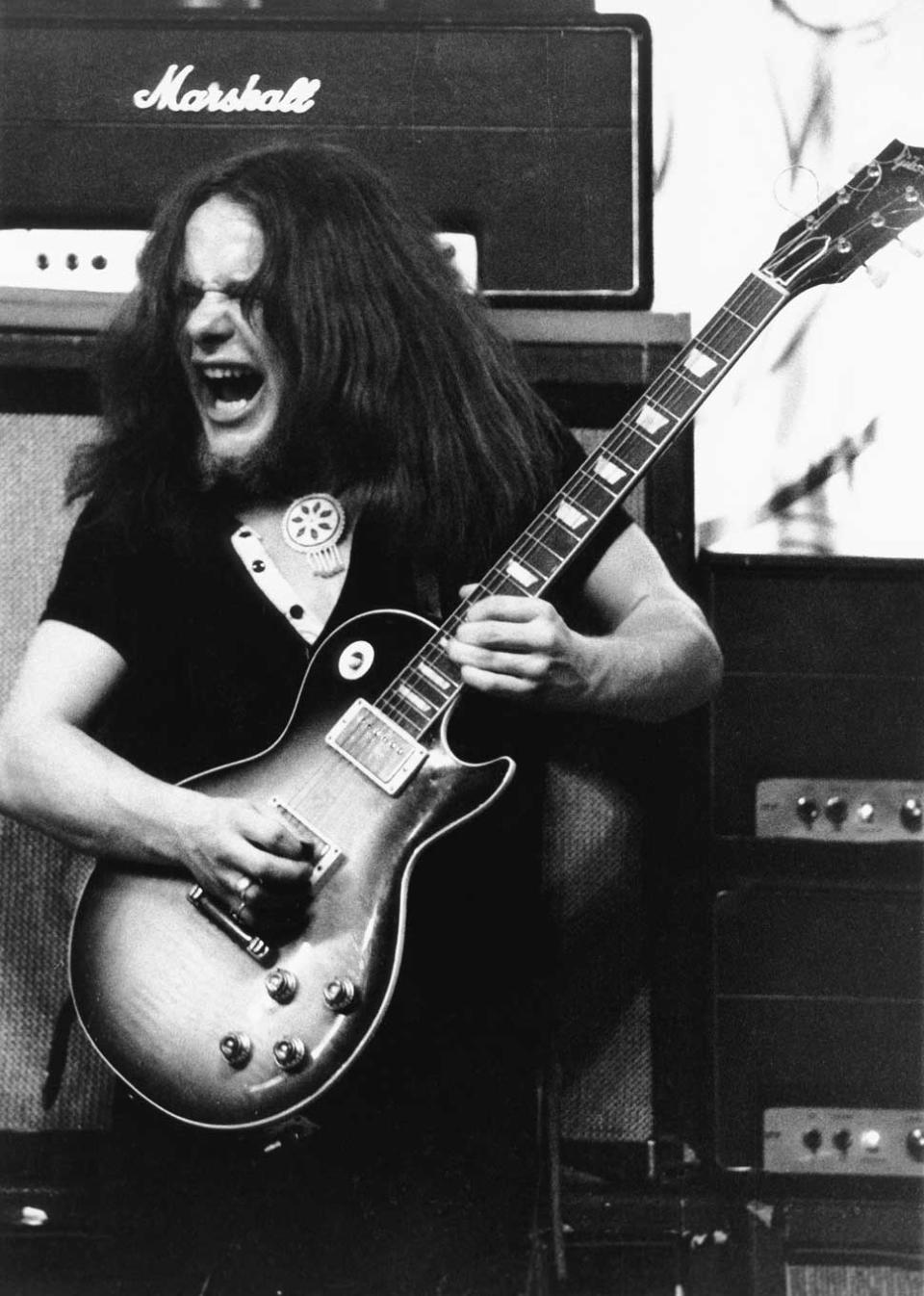

Tons Of Sobs was recorded and produced by Island’s in-house ‘mad professor’ Guy Stevens in a week. Walk In My Shadow and a swaggering take on Booker T And The MGs’ The Hunter bottled the aggression John Glover witnessed at the showcase. Alternatively, the Rodgers/Kossoff co-write Moonshine was a bleak, spectral blues. What united these songs was a rawness, and a guitarist whom, to quote Alexis Korner, knew not to play too many notes and knew how “to use silence”.

In January 1969, two months before its release, promoter Geoff Docherty booked Free to play Sunderland’s Bay Hotel. Docherty had heard about “this new group with a brilliant guitarist” but quickly realised their name was misleading when punters turned up expecting to get in for free.

Despite the sparse audience, Free played a dynamic set. “They had this energy, as if they wanted to prove themselves,” says Docherty. Kossoff, the pint-sized superstar with the lion’s mane hair-do, made an immediate impression: “He walked on, plugged in and just unleashed those solos. But backstage there was a modesty about him. I’d dealt with plenty of musicians who fancied themselves, before and since. Paul Kossoff wasn’t one of them.”

Tons Of Sobs arrived in March. It failed to chart, but Melody Maker described Free as “a group to watch in the 70s”. There was no time to pause or reflect. When they weren’t out and about playing one-night stands and negotiating Britain’s primitive motorway system, Free were in the studio.

A second album, simply called Free, emerged in October. Rodgers and Fraser wrote every song, except the group-credited Trouble On Double Time. The two had become a songwriting partnership under awkward circumstances. Rodgers had caught gonorrhoea and moved into Fraser’s mother’s house in Roehampton to recuperate. The album cover offered an ant’s-eye view of a woman, sprinkled in stardust and silhouetted against the sky. Mouthful Of Grass, I’ll Be Creeping and Lying In The Sunshine were a celebration of peace, love, Mother Nature and sex… lots of sex.

Chris Blackwell had produced the finished album. But as John Glover observes, “It was Free against the world. They didn’t let anyone else in.”

Another relationship was also suffering. Kossoff was not a prolific writer and had begun to feel excluded from the Rodgers/Fraser clique. Free’s new songs also needed a more rhythmic approach – not Koss’ strong point. Free’s engineer Andy Johns recalled Kossoff “getting embarrassed and uptight” when Fraser had to ‘teach’ him his parts.

One afternoon, he slipped away to audition for The Rolling Stones. But the job of replacing Brian Jones went to Mick Taylor instead. Koss crept back to Free before anyone noticed. It was years before the rest of the group found out.

Chris Blackwell was desperate for Free to have a hit, but he’d have to wait a little longer. Nevertheless, everywhere Kossoff turned, there was another musician ready to shower him with praise. In July, Free joined Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood’s new group Blind Faith on a US tour. One night Clapton approached Kossoff in the dressing room and asked, “‘How the hell do you do that?’ talking about my vibrato,” recalled Kossoff. “And I said, ‘You must be joking!’”

When it came to recording their third album, Fire And Water, Free went straight from the gig to the studio, with little time to draw breath. Mr Big and Fire And Water’s title track were masterclasses in economy and space. “I hate to play just solos,” said Kossoff. “I prefer to hear [Rodgers’] voice and back it up or push it – without covering it up.” But the song that most impressed Chris Blackwell was All Right Now, with its bullish riff and terrace-chant chorus.

Free clashed with Blackwell when he insisted they edit it down for a single release. But, for once, they did as he asked. All Right Now was released in May 1970. Free were on tour when they were told the single had jumped from No.30 to No.4 and they were due on Top Of The Pops the next day.

Few groups in the history of the show would look as uncomfortable as Free did half-miming to All Right Now. But the song changed them overnight, and Fire And Water became the first Free album to crack the Top 20, reaching No.2. Melody Maker called it ‘Freemania!’ But the group faced a dilemma. “We were always a rock/blues band,” says Rodgers. “But a rift in our direction did start to become obvious – between the authentic and the obviously commercial.”

In August, Free played to 600,000 at the Isle Of Wight Festival alongside The Who and Koss’ idol, Jimi Hendrix. Footage from the show captured them at the height of their powers; Kossoff wincing and gurning as if every note played was having a physical effect on his being. But as Simon Kirke glumly admitted: “The huge irony is that was the beginning of the end.”

Just five months after the release of Fire And Water came Highway. It was an album that epitomised Free’s creative tug of war. Kossoff considered its soulful slow blues Be My Friend “the best thing we’ve ever done”. But it wasn’t All Right Now. When Free’s next single The Stealer tanked and Highway stalled outside the Top 40, the rows began.

Island blamed the band, the band blamed Island; everyone blamed Highway’s insipid cover. Worse still, Andy Fraser and Paul Rodgers were clashing: Rodgers resented the bass player’s self-appointed leadership; Fraser thought the band’s singer looked down on him. “When those two fell out, it all fell apart,” says Glover. Free played a ‘final’ show at Sydney’s Randwick Racecourse on May 9 1971, and then flew home – separately.

The posthumous Free Live! album arrived six months later. Fraser quickly put together a new group, Toby, and Rodgers formed a trio, Peace. Kirke found the break-up hard, but Kossoff was devastated. It kicked the stuffing out of him,” says Glover. “It was the same for Simon. But Simon got over it. Free was Kossoff’s life.”

Paul Rodgers’ description of Paul Kossoff’s “intense, emotional” relationship with music is reinforced by his reaction to Jimi Hendrix’s death. Kossoff had to be dissuaded from abandoning the Highway sessions and taking the next plane to Seattle for the funeral. “I went through a big Hendrix thing, where I was infatuated by him, his music and his death,” he admitted.

Following the break-up, Kossoff moved into a house in Golborne Mews, off London’s Portobello Road, and turned it into a drug den/shrine to Jimi. “Every time I walked into that house, Koss was listening to Hendrix,” says keyboard player John ‘Rabbit’ Bundrick now. “I used to wonder why, but Koss wasn’t copying Hendrix’s licks, he was tapping into his soul.”

Texas-born Bundrick had seen Free play the Houston Coliseum: “And I had this intuition I would play with them one day.” Rabbit worked with Johnny Nash and Island’s new signing Bob Marley before arriving in London in 1971. Soon afterwards, he’d joined Kirke, Kossoff and Japanese bassist Tetsu Yamauchi in the studio, and the Kossoff, Kirke, Tetsu & Rabbit album was underway. KKTR’s rootsy blues and funk rock lacked Free’s bite and, most importantly, Paul Rodgers’s voice. But it was Island’s way of getting the guitarist working again.

“I’d spent four, maybe five years, being one fourth of a whole personality which was Free,” Kossoff told music paper Sounds. “And when the band broke up, I was on my own. I didn’t know what to do.”

The absence of Free left a hole in Kossoff’s life, which he was now filling with drugs. It happened quickly and took everybody by surprise. Everyone smoked dope – sometimes too much dope – but Kossoff had acquired a taste for the powerful sedative Mandrax. He’d spend days and nights slumped on the sofa in Golborne Mews, Hendrix playing, as dealers and hangers-on drifted in and out. Koss’ girlfriend, Sandie Chard, tried to reason with him – “She stuck around. She was good,” says Glover – but it was no use.

“Koss was a mild-mannered and generous kinda guy,” explains Rabbit, “and that made him an easy target.”

“Friends gave him pills, thinking they were doing him a favour,” adds John Glover. “Then there was this dreadful doctor in Harley Street, who’d write him a prescription for whatever he wanted.” Before long, Koss was swallowing as many as 20 Mandrax a day.

Kossoff’s parents tried to intervene. But his addiction meant he resented their help. That winter, Andy Fraser was so concerned that he and a roadie broke into the mews house, clambered over the bodies passed out on the floor and ‘kidnapped’ Koss. The guitarist stayed with Fraser for 10 days in Sussex. But he was scoring again as soon as he was back in London.

As Christmas ’71 came around, John Glover realised neither Peace or Toby would ever replace Free. “They were… okay,” he says diplomatically. “But they weren’t Free. So I started having conversations with Paul and Andy individually, because I couldn’t get them in a room together. I said, ‘Look, Koss has gone off the rails. How about we help him and put the band back together, just for a tour?’”

Free reunited in January 1972. “They sort of dragged me out of my pit,” admitted Kossoff. It was what he wanted, but not enough for him to curb his drug use. On tour, Koss could be perfectly lucid one minute, but when the Mandrax kicked in, he’d struggle to find the switch on his amp.

At a gig at Newcastle City Hall, he collapsed after playing just two numbers.

Despite Kossoff’s unpredictability, nobody wanted to give up, and Free were soon back in the studio. Richard Digby-Smith co-engineered their next album, Free At Last. “There was a lot of recreational drink and drug activity going on,” he says now. “And Paul would go off into a dream-like state more than the rest of us.”

Frustratingly, when Kossoff was straight he could still play beautifully. “That guitar and him were as one,” says Digby-Smith, who watched, amused, as another unnamed guitarist picked up Koss’ Les Paul, switched on his Marshall amp and struggled to play a note. “It started howling and feeding back. But the fact is nobody but Kossy could play that guitar through that amp.”

Free At Last arrived in June ’72, and gave the group a Top 20 hit with Little Bit Of Love. But getting Kossoff to recreate what he did in the studio on tour was hard. Once again, it all fell apart in Newcastle, where he had a seizure backstage at The Mayfair. His body had gone into shock from Mandrax withdrawal.

“The doctors told me if he carried on like this, he would die,” says Geoff Docherty. Geoff had promoted enough Free shows to know they were on the skids: “Paul’s playing had gone downhill, and you could see the frustration in Paul Rodgers’ face at the end of every song.”

Andy Fraser was the first to walk, quitting on the eve of a Japanese tour: “I couldn’t bear to see what Koss was doing to himself.” But when Kossoff went for a course of neuroelectric therapy – the ‘black box’ treatment that helped cure Clapton’s addictions – Free went to Japan without him. Tetsu and Rabbit Bundrick were drafted in, and Paul Rodgers played guitar.

Come October, a clearly un-cured Kossoff joined the ‘new’ Free of Rodgers, Kirke, Tetsu and Rabbit to start work on a new album. Its appropriate title was Heartbreaker.

Rodgers’ song, Come Together In The Morning, was written indirectly about Kossoff. ‘It makes me sad to think of you/Because I understand the things you do/There is no one else can take your place’ he sang. “Kossoff’s solo in that very song rips my heart out,” says Rodgers now. But Kossoff was in no state to play every solo on the album, not least when he was discovered fast asleep and snoring between takes.

Instead, Rabbit Bundrick’s Texas pal, Stray Dog guitarist Snuffy Walden, was brought in to play where necessary. “The one time we actually sat down and talked,” said Walden, “Koss was a real gentleman. He knew he was blowing it and he knew I wasn’t after his job.” Walden apparently played on three tracks on the final album and on various versions of Wishing Well.

Heartbreaker, released in January ’73, showcased a new, bigger-sounding Free. Both the album and the single Wishing Well went Top 10. But when Free began a US tour with Traffic, Kossoff stayed behind. The press were told he was busy working on a solo album. In fact, he’d recently gone to Jamaica for a spell of rest and recuperation, only to discover Mandrax was available at every pharmacist on the island without prescription. Free toured with Osibisa guitarist Wendell Richardson instead. “God bless Wendell, but he wasn’t Koss, and this wasn’t Free,” says Rabbit Bundrick.

“I flew down to see them somewhere on that tour,” sighs John Glover, who remembers Rabbit smashing up a dressing room and various band members sporting black eyes and split lips. “Paul Rodgers said, ‘That’s it. At the end of this tour, I’m gone.’ And that was it. That was the end.”

Free played their real final show at Miami’s Hollywood Sportatorium on February 17, 1973.

The phrase ‘the lost years’ is frequently used when discussing the careers of troubled rock stars. However, in Paul Kossoff’s case, parts of 1973 and ’74 were lost to his escalating drug use, which, for a time, also included heroin.

Kossoff’s solo album, Back Street Crawler, slipped out in November ’73. The cover showed a raddled-looking Koss next to a dustbin in Golborne Mews. Several Island musicians played on the record. But it wasn’t quite the collaborative effort it appeared to be. “There were always lots of jam sessions at Island,” says Digby Smith. “And we also had reels and reels of Paul playing on his own.” Molten Gold, with Paul Rodgers on vocals, and the John Martyn collaboration Time Away were exquisite reminders of just how good he could be.

In the meantime, though, his ex-bandmates were moving on. Fraser formed a new group, Sharks, and Rodgers and Kirke paired up in Bad Company. John Glover is certain Kossoff played in an early five-man line-up of Bad Company, and has the tape to prove it (“Rodgers won’t let me put it out.”). But he was too stoned, too unreliable, and the group continued without him. Within a year, Bad Company’s debut album was a US No.1 hit.

Instead, Kossoff meandered between jam sessions and occasional pub gigs. He played with Spooky Tooth’s Mike Kellie and Peter Green (see side panel). But nothing long term came of these collaborations. He also cleaned up, sometimes for weeks at a time. Around autumn 1974, David Kossoff called John Glover and told him Paul was drug-free. Glover was impressed by Koss’ playing, and approached Chris Blackwell for a record deal. Blackwell wrote him a cheque for £20,000 on the spot. But when Kossoff went on another bender, Glover sheepishly returned the money.

Around this time, Geoff Docherty came back into Kossoff’s life. Docherty was now managing Beckett, a group with a fine blues/soul singer named Terry Slesser. Docherty had heard about Kossoff, thought he could help, and drove down from Sunderland to Golborne Mews. He was appalled by what he found.

Sandie was making cups of tea and trying to maintain an air of domesticity. “But Paul was unconscious,” says Docherty. “Then there was a knock at the door and a dealer outside. Sandie shook Paul awake, and then he crawled on all fours – like a dog – pulled a cheque book out of the drawer, signed this cheque and handed it to the dealer.”

Docherty phoned David Kossoff and told him he was taking Paul to Sunderland, right now: “If I don’t, he’ll die.” Kossoff was bundled into the van and didn’t utter a word for the entire journey.

Docherty moved Kossoff into his 12th-floor flat in a Wearside tower block, and began a cold turkey/boot camp regime. “I fed him grilled fish, spring cabbage and orange juice,” he recalls. “And I wouldn’t let him use the lift – I got him walking up them stairs, all 24 flights.” It wasn’t easy. Kossoff had been prescribed Mogadon to help with his withdrawal. Docherty hid the pills in his oven, and rationed them out, until Kossoff found them and tried to take a handful at once. When Geoff intervened, he threw a telephone at him, narrowly missing his face. Docherty, a former doorman, was not to be trifled with: “I warned him, ‘If you ever do that again…’”

After a few weeks, Kossoff was deemed well enough to visit Annabel’s nightclub on the tower block’s groundfloor. Docherty allowed him to drink alcohol, but the guitarist insisted on crème de menthe, not the most popular drink in Sunderland: “So I went round every pub in town, buying whatever they had left in the bottles.” At the end of the night, Koss would stagger up the 24 flights, with Docherty goading him on like a regimental sergeant major: “And it worked. He got well again and said he wanted to put a band together.

Docherty brought in Terry Slesser, a local bass player and drummer and hired a rehearsal space above a bowling alley. “Paul had been playing every day, and they sounded great. I thought, ‘I’m onto a winner here’.”

But it wasn’t to be. Kossoff eventually called John Glover and moved straight back to London. “It was difficult,” admits Glover. “Geoff was the top promoter in the north east, but I was the manager and this is what I do.”

In January ’75, to test Kossoff’s reliability, Glover put him on the road with John Martyn: “He played a few songs a night with John, and it was great – for a couple of weeks. Then he got hold of some pills and disappeared at Watford Gap service station. Gone, for two days.”

Once again, though, Kossoff cleaned up, and slowly assembled a new band: vocalist Terry Slesser and three Americans, keyboard player Mike Montgomery, bassist Terry Wilson and drummer Tony Braunagel. To help maintain Paul’s drug-free state, David Kossoff moved him into a house in Tilehurst, a suburb of Reading.

The band now calling themselves Back Street Crawler played several shows that made up for in energy what they lacked in finesse. “At which point,” says Glover. “Ahmet Ertegun came into the picture.” Ertegun, the Atlantic Records mogul who’d signed Led Zeppelin and The Rolling Stones, signed Back Street Crawler and publicly declared Paul Kossoff ‘the emperor of the blues’. The deal was reported as being worth a quarter of a million dollars. Glover insists it was $150,000. “There was no going back now,” he admits, “so we had to keep Koss in as good a nick as we could.”

John Taylor was hired as Back Street Crawler’s tour manager and Kossoff’s occasional minder. “Paul was a lovely person,” says Taylor now. “But too easy and too easily manipulated.“

Taylor quickly noticed Paul’s fractious relationship with his father. “David was trying to get him off the stuff, but Paul didn’t get on with his dad at all. David was a bugger for that Dymo tape, where you can print out words. I remember getting into Koss’ car and his dad had stuck these typed-out instructions on the dashboard: ‘Are you fit to drive?’, ‘Turn on headlights’…”

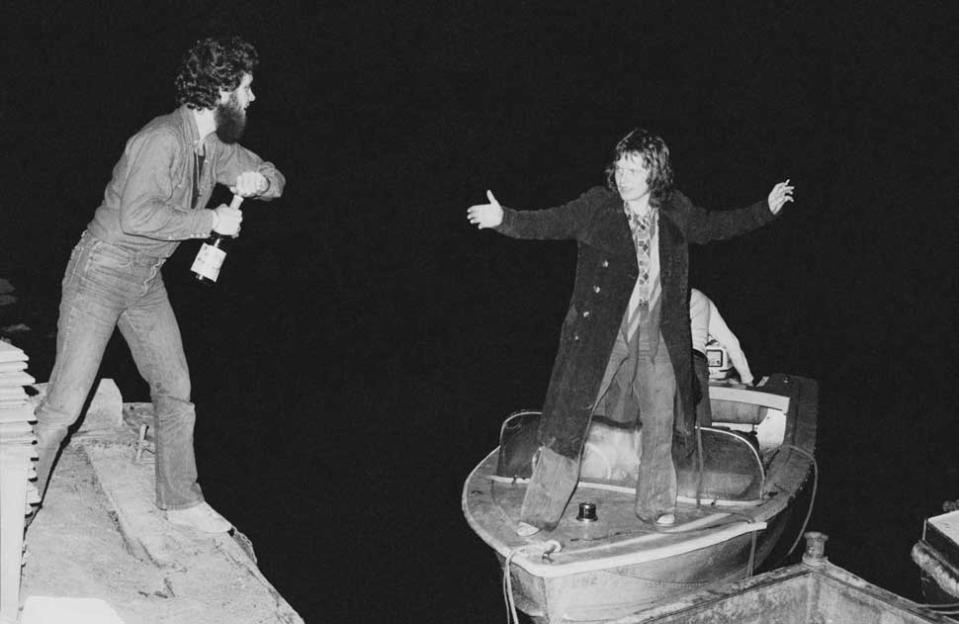

That said, after Back Street Crawler were photographed signing their contract at London’s Olympic Studios, Kossoff climbed out of the bathroom window, jumped into his car and proceeded to crash into several stationary vehicles. “And then he dumped his car and walked home,” recalls Glover, who witnessed the carnage.

In September, the band were due to play a festival in Belgium to launch their debut album. Taylor was tasked with driving Kossoff to the airport in the morning. He stayed the night at Tilehurst, only to be woken by Koss and an unexpected house guest. “It was Lemmy,” he sighs. “God only knows how Lemmy ended up there, or what he and Koss had being doing.”

On the drive to Heathrow the next day, Kossoff was barely coherent. When a policeman spotted Taylor half-carrying him towards the terminal, he threatened to arrest them both unless they left the airport.

Back Street Crawler’s debut album, The Band Plays On, arrived in October ’75. It had its moments – the lolloping funk blues Train Song, for one – but was too run-of-the-mill to compete with Bad Company.

Sadly, Kossoff’s declining health had grabbed the headlines ahead of his new album. Kossoff was taken ill shortly before the band’s first UK tour. He was rushed to hospital, slipped into a coma, after which his heart stopped and he was ‘dead’ for 35 minutes, until doctors resuscitated him.

“I filled my body up with toxins and ended up that way,” he explained. “I think everyone has some sort of death wish,” before adding, “But I don’t want to die.”

John Taylor visited him in north London’s Northwick Park Hospital 10 days after his ‘death’, and was shocked by the transformation. Kossoff had burns on his chest from the defibrillator, but “his face was clean and pink and he’d detoxed completely. I’d never seen him look like that good before. And what happened? He went back on tour and didn’t have a hope of staying clean.”

Shortly after, Kossoff gave an interview to Bob Harris on the BBC’s The Old Grey Whistle Test. His speech was slurred as he declared his fellow guest, singer Leo Sayer, “better than Paul Rodgers.”

“Koss was with a girl that day – somebody’s wife in the business who was a well-known smackhead,” recalls Taylor.

The subsequent UK tour saw flashes of the old Kossoff, but far too many moments of high farce and terrible chaos. Koss often fell over on stage, forgot the chords or gave long, stoned, rambling speeches. “I recorded every show and gave him a cassette afterwards,” says Taylor. “Sometimes it was, ‘Hey, Koss, listen to this. Other times, ‘Hey, Koss, listen to that, you cunt!’”

Kossoff was delighted when old friend Rabbit Bundrick replaced Mike Montgomery. But as Back Street Crawler headed to the US for more dates and recording sessions, Rabbit realised his friend was in trouble. “The thing that kept messing up Koss was the outside world getting to him,” says Rabbit. On one occasion, bassist Terry Wilson kicked Koss’ door in and physically removed a dealer from his hotel suite.

A second Back Street Crawler album, 2nd Street, was pieced together in between dates, in studios around America. But disaster had struck early in the tour after Kossoff attacked John Glover with a whiskey bottle. Glover tried to defend himself. “And I broke two of his fingers,” he says, adding sarcastically, “Great, what a fantastic thing to do.” Once again, Snuffy Walden was hired to play, and Kossoff reduced to introducing his own band on stage and then watching the show like a regular punter.

Even now, though, he still had moments of great clarity. When the rest of the group couldn’t make it in time to a gig in Connecticut or New Jersey, Kossoff managed to calm the angry promoter. “He came out on stage and talked to the audience for an hour,” recalls Taylor. “It was a one-man stand-up show. He was a raconteur and an entertainer. It was great fun to see.” It was also something his father would have done.

Koss’ fingers finally healed and the tour ended on an unexpected high. In March, Back Street Crawler were due to play Los Angeles’ Starwood Club, on the same nights as Bad Company played The Forum. Kossoff was delighted when the band showed up at the Starwood, and Rodgers and Kirke jumped up on stage to jam with them. That night, Koss didn’t fall over and didn’t forget the chords. Instead, he played like the old Paul Kossoff.

“Backstage afterwards there was champagne flying everywhere, like the Grand Prix,” remembers John Taylor. “Koss was great, really together, really on it,” says Paul Rodgers, “and that was the last time I saw him.”

John Taylor remembers eating breakfast in Los Angeles’ Hyatt House the morning after the Starwood show, when Kossoff walked in and asked John Glover for money. “And everybody knew what he wanted it for.”

Taylor, Glover and the band, except for Rabbit and Terry Slesser, were due to fly to New York that night with the master tapes for 2nd Street. Taylor didn’t see Kossoff again until the evening.

“I remember walking down this long corridor at the airport and looking over at him and he was… sort of… I dunno, radiating,” he says, struggling to find the right words. “It was almost religious. I don’t know what he’d taken.”

Taylor sat with Kossoff after take-off. But the flight was undersold. “He saw the empty seats and said, ‘I’ll have that row there…’ That was the last thing he ever said to me.” The next thing Taylor remembers is being prodded awake by a stewardess as they approached JFK. She told him to put his seatbelt on and asked where “the guy sitting next to me” had gone.

Nobody else remembers Kossoff leaving his seat. He just wandered off at some point during the five-hour flight. Apparently, it took the crew some time to gain access to the bathroom, as his dead body was slumped against the door. “We were held on the plane for an hour, while the authorities argued over where Koss had died – LA or New York,” says Taylor.

Contrary to rumour, Kossoff hadn’t overdosed. The cause of death was given as ‘cerebral and pulmonary oedema’; a legacy of the previous year’s cardiac arrest.

Taylor had the unenviable job of arranging to transport the body to England, while John Glover told everyone the bad news. Simon Kirke was informed just before a Bad Company show in New Orleans, but decided not to tell Paul Rodgers until some days later, so as not to jeopardise the tour.

Five months before his death, Kossoff told a journalist, “There’s nothing outside music, I have no hobbies, I just want to play.” That was always part of the problem. Everyone who talks about Kossoff says

that had they known then what they know now, his story might have had a happier ending. “We had no tools to help him,” says Paul Rodgers, “unlike today.”

Rodgers is convinced that had he lived, the two of them would have “undoubtedly worked together again”. In 2014, Rodgers met Kossoff’s son, Simon, for the first time. They’ve stayed in touch ever since. “It’s so tragic because he didn’t get a chance to know his father,” he says. “But looking into his eyes is like looking into Paul’s."

In the meantime Kossoff’s legacy endures. Like their creator, those slow sustained notes, measured solos and moments of perfect silence never had the chance to grow old.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock magazine in 2016.