The story of John Kalodner, the man who made rock stars

John Kalodner was the music business guru who signed Foreigner, rescued Aerosmith and conquered America with Whitesnake. A controversial figure – Whitesnake guitarist John Sykes described him as "exasperating to the point where you want to rip your fucking hair out" – he was also responsible for Cher's resurrection. In 2005, Classic Rock looked back at Kalodner's career and got his side of the story. He retired from the industry the following year.

Record company A&R men (it’s short for Artist & Repertoire) come and go. One of them, however, seems to have been around forever – and will likely be around long after we’re gone. When it comes to spotting talent, the list of those for whom he has given a leg up speaks for itself. You might not know what he looks like, but if you read Classic Rock you probably know his name: John Kalodner. He’s one of the most charismatic, visually arresting and successful people in the music business.

He’s the man who signed Foreigner when no one else gave a toss about them. And his remit has always gone far beyond finding and signing a band (which is what many people think an A&R man’s job is); he helps artists to polish their material, points them towards an appropriate producer to work with, and much, much more. ‘Guru’ is perhaps a better, more appropriate job title. His role in Foreigner’s success story became so unique that when it came to the credits for their second album, Double Vision, in 1978, all that guitarist Mick Jones could think of was ‘John Kalodner: John Kalodner’. That same credit has since appeared all over the place and on some landmark albums.

“I wasn’t the record’s producer, the engineer, his manager or the art director, I was just doing what I did best,” the quietly spoken Kalodner explains. “I’d say: ‘That song could be better’; ‘The lyric’s not right’; ‘You could improve the melody or the chorus’. Lots of people think they can do that, but very few of us are really able to.”

Since it was introduced on the Foreigner record, the ‘John Kalodner: John Kalodner’ credit has appeared on more than 100 other albums, many of which you will undoubtedly own.

Kalodner was the record company executive who rescued Aerosmith’s career. Steven Tyler and Joe Perry’s gratitude extends to a famous appearance he made as a bearded bride in the video for Dude (Looks Like A Lady). But some of those that Kalodner has sprinkled his fairy dust on have short memories. In some ways the negativity he inspires is understandable. Thorny and opinionated, Kalodner doesn’t suffer fools gladly – if it all.

“My man management skills are very poor, but the music that gets made is usually worth it,” he says. “When the record comes out, I suspect most people try to forget they dealt with me at all.”

These days he works for Sanctuary Records, and today he’s in London to handpick the tracks that will make it onto the debut album by his latest discoveries, the young, London-based hard rockers Hurricane Party.

“Their album’s spectacular and has a possible huge hit,” he enthuses. “Hurricane Party are a talent on a par with all my previous bands.” An accolade indeed.

Kalodner began at the bottom of the ladder, working in a record shop, and then managed a band that later evolved into The Hooters. He then moved into music journalism, also took photographs, and helped build a rock club. He can’t, however, play a musical instrument.

“People say: ‘What do you know? You can’t even play’. But I have other talents. Billy Idol never had anyone tell him: ‘The verse is too long. Get to the chorus quicker’. I recognise those things very early. He’s Billy Idol and he’s great, but that doesn’t mean things can’t be improved.”

It was Atlantic Records president Jerry Greenberg who allowed Kalodner to listen to some of the demo tapes that arrived at the label daily. “But in my own time and on my own cassette machine,” he adds. His first signing, in 1977, was Foreigner, a band that just about every other label had turned down. “They played Feels Like The First Time, the rest is self-explanatory,” he says. “You hear Lou Gramm singing that song in a rehearsal room, no explanation is necessary.”

The band’s self-titled debut album eventually went quadruple-platinum. Not a bad start. Being hired by record label boss David Geffen was, he says, “the most exciting time in my life. Those days will never be replicated. The record business was in a boom-time; horizons were unlimited.”

Although Geffen Records were a maverick company, Kalodner says ‘maverick’ did not apply to David Geffen: “He interfered just twice, and for personal reasons. He wouldn’t let me sign Ozzy Osbourne because he hated Don Arden [Ozzy’s then manager, and the father of his wife/manager Sharon]. Such things were unusual, because David also hated Brian Rohan, who was Aerosmith’s attorney, and yet we still signed Aerosmith.”

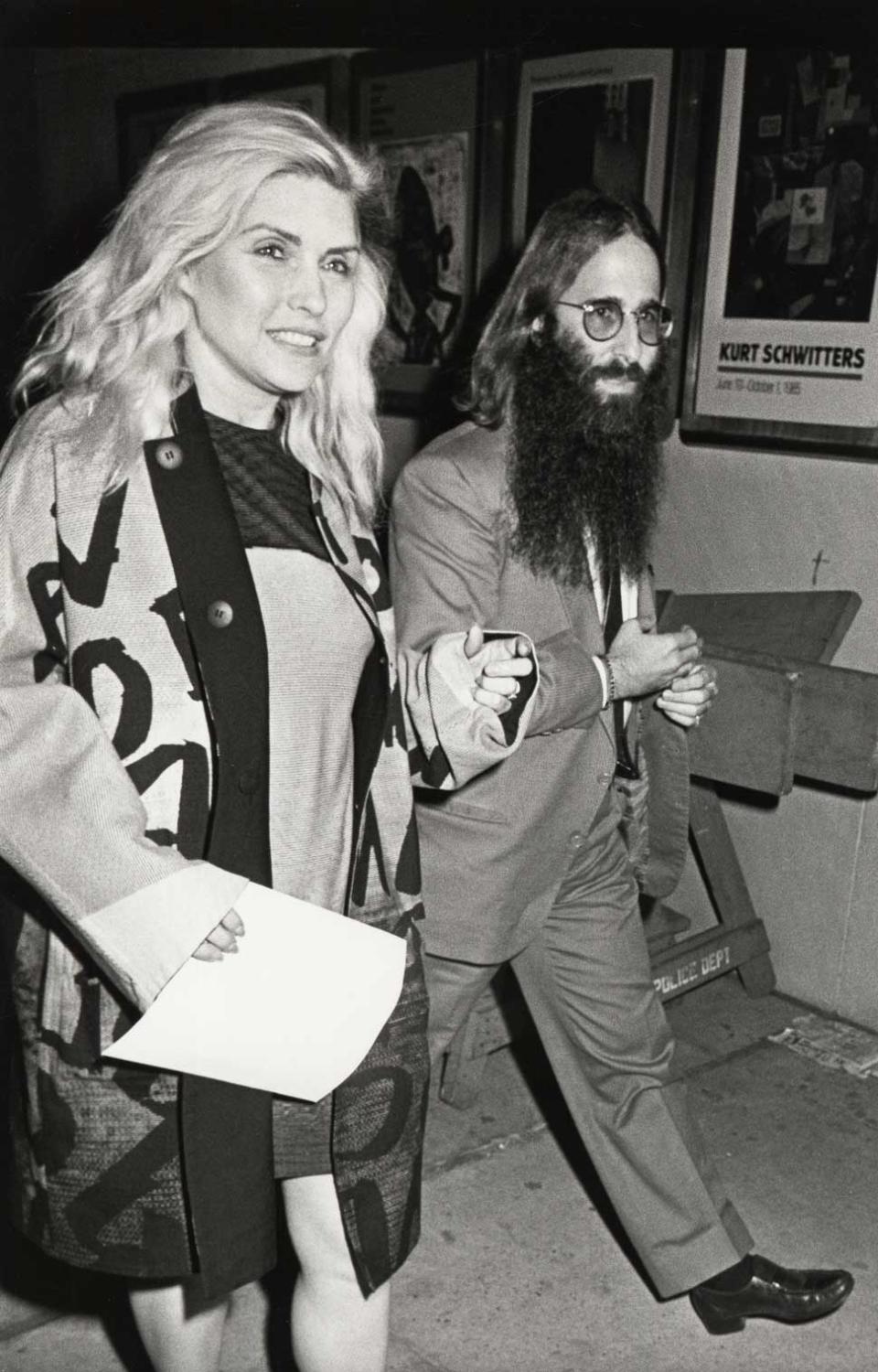

Kalodner’s John Lennon-style beard is these days a trademark. He last shaved back in 1970 at his mother’s insistence. Apparently, it paid off: Joe Perry once claimed that Kalodner’s facial growth helped convince Aerosmith to sign to Geffen.

“I don’t know if they knew – or cared – a crap about who I was,” he says now. “I’ve no idea why they signed with Geffen as opposed to our rivals.”

No matter. Despite Aerosmith’s perilous situation at that time, Kalodner and band manager Tim Collins masterminded a highly unlikely second run of success.

“Done With Mirrors, the first record I made with them, stank,” Kalodner admits. “Aerosmith were still great artists, but high and unprepared. If Tim Collins hadn’t cleaned them up there’s no way they’d have survived.”

A lifelong teetotaller, Kalodner now realises that Collins kept him out of Aerosmith’s way. “When you don’t drink or take drugs, it’s hard to become part of a band’s inner circle,” he states. “I’m fortunate that I had no idea of the extent of their problems back then. All I knew was that I wanted to make records, be famous and fuck girls. Being a famous A&R person was all that mattered to me.”

Success with Aerosmith and, later, Sammy Hagar allowed Kalodner to sign a new supergroup, Asia, to Geffen. But, as Kalodner now rues, “the project was ruined by [bassist/vocalist] John Wetton being a drunk. The drinking and fighting made me so sad; I consciously attempted to forget it all. We worked so hard to make it happen, to see it all unravel was truly horrible.”

With Whitesnake Kalodner again conquered the charts. But David Coverdale’s inability to sing for 18 months made their 1987 album “the most difficult thing I ever worked on,” Kalodner recalls. “It was almost impossible to get him to finish the record. David is one of the greatest singers ever, but you really wouldn’t have known that at the time.”

Were his problems emotional or physical?

“Both. David had sinus problems, so he had an operation. [Producer] Keith Olsen was able to coax out those incredible vocals. To some extent it was physical, but it was also in his head. I came to London to see his Hammersmith show [in October 2004]. I was there with Jimmy Page, and we just marvelled at his singing.

“Am I still friends with David?” he says, repeating the question as he thinks about the answer. “Most artists resent me because I have to change their music, and that never leaves them. At this time of my life, towards the end of my career and 55 years old, I feel that they’ll still see me but would be happy not to work with me any more – especially those who don’t rely on records for their income, like David Coverdale or Aerosmith. It’s hard to accept, but true.”

Despite his many successes, Kalodner still harbours a wish for the dream team of himself, Coverdale and one-time Whitesnake guitarist John Sykes to be revived.

“Despite all the problems, it’s something I think of every single day,” he admits. “I know that John Sykes would do it in a heartbeat too. But for whatever personal reasons, David Coverdale just isn’t interested.”

Kalodner was also involved in the Coverdale-Page project, which he now admits was “ill-conceived”.

“Nobody could replace Robert Plant,” he says. “Jimmy Page is the greatest guitar player in the world, but the magic between him and Plant could never be replicated. I failed to realise that at the time.”

Kalodner was also at Geffen during the astonishing rises of both Guns N’ Roses and Nirvana. Of GN’R he says: “When I saw them at the Santa Monica Civic for the first time, I knew they’d be huge. Nobody could quantify exactly how big, but when your singer comes out in a kilt, you know they have balls. Axl could sing and wasn’t afraid of anything.”

Kalodner is one of only a few people who have met Axl recently: “I saw him in the Sanctuary office a month ago. This guy walked by and says: ‘Hello, John’. It was Axl. And he looked great – like Axl The Rock Star again. He did those last shows and he just wasn’t himself any more.”

Unfortunately, the meeting didn’t throw any light on the long-running saga of GN’R’s Chinese Democracy album, and Kalodner remains as uncertain as everyone else over whether it will ever be released – or even finished. He mentions that the New York Times did a whole article on the making of that album, and says: “All of it was true. They did spend all that money, and they’ve been working on it since I left Geffen – 11 years ago!”

If Kalodner was still at Geffen, does he think money would continue be shovelled into Chinese Democracy? “Well, I wasn’t their A&R man,” he says. “But if we were talking about a Journey or an Aerosmith record, then definitely not. But with someone as unpredictable as Axl, anything’s possible. I honestly couldn’t speculate.”

Kalodner met Kurt Cobain only rarely, but says he recognised right away what “a huge, important record” Smells Like Teen Spirit would become, “although obviously I didn’t realise it would ruin rock music.” But Kalodner doesn’t believe the ensuing musical clearance sale was strictly necessary.

“No,” he says. “Some of the music that came out of the grunge scene was great, but it ruined careers that didn’t need ruining. The unbelievably talented Tom Keifer [Cinderella vocalist/guitarist] would be an example. Poison, who were maybe initially a joke, were also extremely talented. A lot of careers were caught in front of the train. It’s hard to understand. Obviously it’s a sociological thing; teenagers and 20-year-olds made those decisions.”

Another career resurrection that Kalodner will take full responsibility for is that of Cher, beginning with her 1987 album Cher and following it with another pair of huge-sellers in Heart Of Stone and Love Hurts. He provided the material, teaming her up with Jon Bon Jovi and eventual beau Richie Sambora plus a team of writers that included Desmond Child, Michael Bolton, Diane Warren and Bob Halligan Jr. It was an inspired move at the time. Now, however, apparently it rankles.

“It was kinda difficult to persuade her,” he reveals, “but she said if I made it easy for her then she’d come in and give it her best shot. So I pretty much did everything; I found the producer, songs and players. It was remarkable. She’s maybe the most focused professional that I’ve ever seen.”

Cher was pretty washed-up at that point, I offer.

“In my mind she was still a superstar,” he protests. “But she didn’t repay my confidence – in terms of money or karma. She’s probably the most selfish, thoughtless person I ever met. I would never work with her again.

“Back in March I went to Sydney to see her,” he continues. “She wouldn’t even see me before the show. I flew halfway around the world and she refused to say hello. I watched part of her show, but walked out of the arena knowing I’d never work with her again no matter what.”

Talking of Jon and Richie, what would Kalodner make of the proposition that Bon Jovi were an average band, but in the right place at the right time?

“That’s 100 per cent false,” he counters. “Jon Bon Jovi is one of the great lead singer performers of his generation, and he and Richie are as good a writing team as Steven Tyler and Joe Perry, or Steve Perry, Neal Schon and Jonathan Cain [Journey].

“It’s funny, I get asked that question a lot. To an American like me their music is great. Maybe it doesn’t hold up to some people’s more critical judgements, but Bon Jovi made some of the most important music of the 1980s.”

Like so many others, Kalodner fails to understand why British rockers Thunder failed to take off in America.

“Everything about them was good: the singer, the guitar player, the songs, the crazy drummer, their vibe as people,” he says. “I thought they’d have been huge. But I was wrong.”

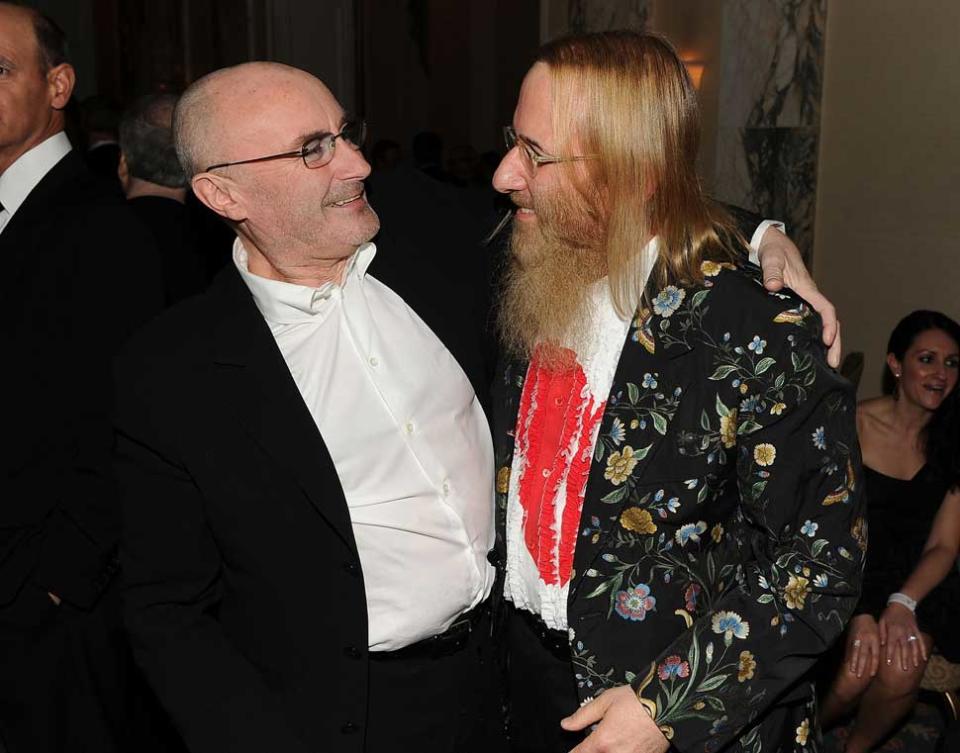

Another ungrateful recipient of Kalodner’s help was Phil Collins, whose 1981 solo debut Face Value was released via Geffen in the US. “David Geffen was going to sign Peter Gabriel, and told me: ‘Why would we want the drummer from Genesis when we can have the lead singer?’ Phil Collins never really talked to me again. So fuck him. I don’t need his shit.”

Leaving Geffen, Kalodner headed to CBS subsidiary Portrait Records, where he attempted to revive the careers of bands including Ratt and Great White. This time he was unsuccessful. We also still await Cinderella’s successor to ’94’s Still Climbing.

“It was unrealistic, but not because of the bands,” he comments. “Portrait just weren’t content with the moderate success of selling 100,000 or 200,000 records. I’m as keen as anyone else to hear something from Cinderella. There’s no more talented a rock musician than Tom Keifer. But I’ve no idea why nothing new has come out.”

Journey guitarist Neal Schon has moaned that you forced them to put too many ballads on their Arrival album.

“Only because their ballads were better songs,” Kalodner protests. “Neal’s among the most underrated musicians ever. I’ve always done everything for him, but he’s a classic example of someone who blames me for almost everything. And yet who’s the first person he calls? Me.”

Which of the bands that Kalodner has worked with was a commercial flop but most deserved to have been enormous?

“That’s a great question. Blue Murder, the band John Sykes had after being in Whitesnake, springs to mind. Zakk Wylde’s Pride & Glory also made a great record that somehow failed to take off.

“I also loved Black ’N Blue. We did four records together and I did everything possible to help them. Even now I’ve no clue why they sold between 150,000 and 200,000 every time. Jon Bon Jovi picked Bruce Fairbairn to produce Slippery When Wet after hearing Black ‘N Blue. Some things are just unexplainable.”

Conversely, the biggest case of a band he’s worked with having achieved sales that outstripped their talent is, he says, Nelson: “The Nelson twins [Matthew and Gunnar] were far more successful than they should’ve been. The first Nelson record [1990’s After The Rain] was great, but they really didn’t have the talent.”

Have you ever considered writing a book?

“If I did write a book I’d want to tell the whole story, and I’m not sure that’s possible right now,” he says. “So I may write it with all the real stories, and give it to a lawyer, to be published upon my death. Come to think of it, that’s a damned good idea.”

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 84, published in September 2005. Hurricane Party changed their name to Roadster after Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans shortly after the interview with Kalodner. Their debut album Grand Hotel was finally released in 2006, but they broke up the following year after their second, Glass Mountain.