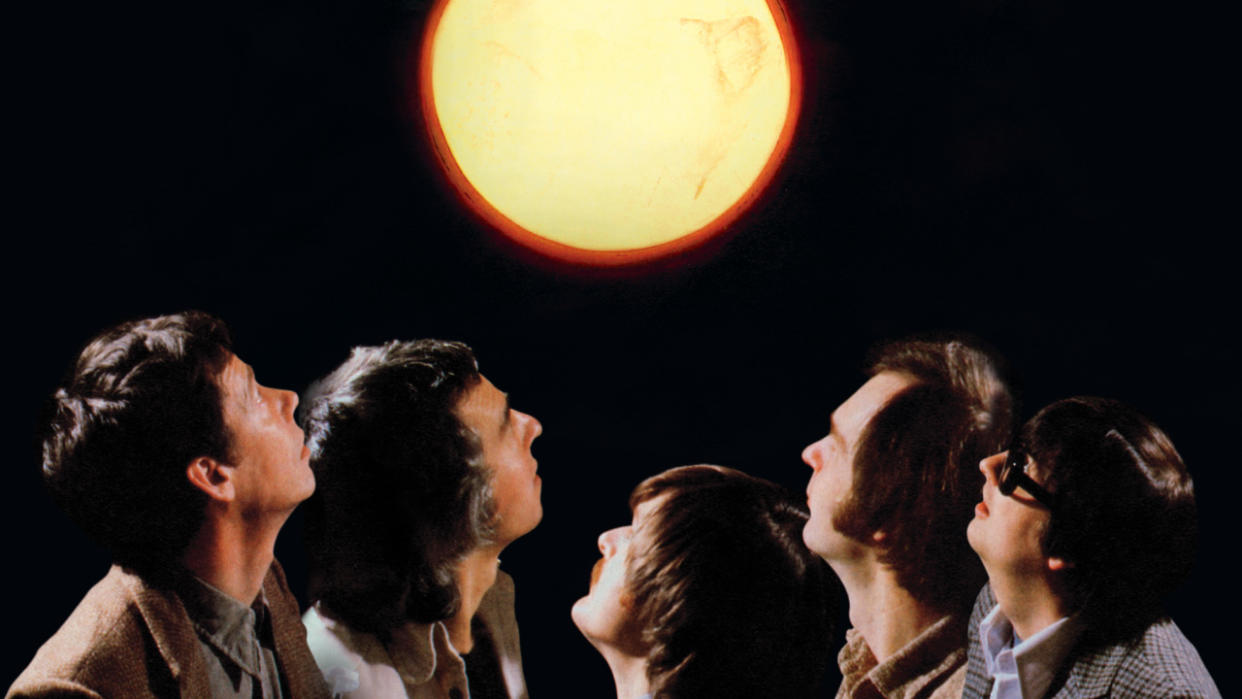

The story of Sky, the least rock’n’roll band of all time

The British-Australian band Sky managed to evade being pigeonholed in a career that merged a wide range of genres. In 2014 Prog explored the history of a group of musicians who just wanted to play good music – and achieved their admirable ambition.

“I don’t know what to put Sky under because they don’t really qualify for electro pop or prog rock,” says Herbie Flowers, still sprightly and “whizzing about like a 26-year-old”.

Fresh from rehearsals for the final tour of Jeff Wayne’s Musical Version Of The War Of The Worlds, Prog asks the no-nonsense session musician to the stars, and one fifth of the Band Who Will Not Be Categorised, whether he believes Sky made quasi-classical prog for mainstream listeners. His reply is terse. “That’s your job,” he says. “My job is a bass player.”

“They had a lot of trouble working out where to put us in record shops,” offers drummer Tristan Fry, no less baffled. “They didn’t know whether to put us under pop, jazz or anything else – even classical.”

True enough: listen to Westway, the opening track from the band’s self-titled debut album from 1979, and it could almost be a jazz funk band. Cannonball, from the same album, has shades of the soundtrack to The Long Good Friday, although that’s hardly surprising because its writer, Francis Monkman, formerly of Curved Air, composed that very movie theme. Dance Of The Little Fairies is a prim little neo-classical piece from 1980’s double album Sky 2, while Tuba Smarties has the vaguely comical air of a novelty tune.

Then there’s Toccata, a Top 5 hit from 1980, which has all the baroque grandeur and pomp you’d expect from a number penned by Johann Sebastian Bach, albeit a souped-up and electrified version. Or the lengthy, multi-part FIFO and Where Opposites Meet, which surely merit contention for Sky’s inclusion in the prog pantheon. Elsewhere, they show signs of being, variously, a neo-ambient and symphonic rock outfit.

“As a schoolboy, I was exposed to Sky’s debut album by an enthusiastic music teacher,” says Sky fan Damian Wilson, singer with Headspace [and formerly Threshold]. “She considered that the best way to appreciate the experience was to lose oneself in it. This was the first album I had been aware of and I was instructed to let go and indulge.

“My complicated musical mix somehow seemed to come together with Sky – they blended the classical influence with the modern, adding great musicianship. I was allowed to close my eyes, head on desk, and drift off away to another place. There I found peace, and I never came back. I’m very much still there.”

It’s hardly any wonder that Sky were hard to pin down, considering their diverse members. Fry was a timpanist with the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Academy of St Martin In The Fields Orchestra, as well as a session musician for everyone from Frank Sinatra to Greg Lake (he played on Lake’s I Believe In Father Christmas) and The Beatles (that’s him on Sgt Pepper’s climactic, epochal A Day In The Life).

He was joined by Flowers, a former member of early-70s hybrid popsters Blue Mink (who had a No.3 hit in 1970 with Melting Pot), writer of Clive Dunn’s chart-topping Grandad, creator of the immortal bassline for Lou Reed’s Walk On The Wild Side and sessioneer for David Bowie, Elton John, Roy Harper, George Harrison and hundreds of others.

There was the aforementioned founder member of – and keyboardist/guitarist with – Curved Air; feted Australian classical guitarist John Williams, whose version of classical piece (and theme to the film The Deer Hunter) Cavatina reached No.9 in 1978; and fellow Aussie classical/rock guitarist Kevin Peek, whose CV was as varied as those of his bandmates, having worked with Jeff Wayne, The Alan Parsons Project, Manfred Mann and scores of others.

How on earth did such a disparate bunch of musicians – a polite sort of supergroup, each of whom had a sufficiently full CV to have been considered leader – form a single unit?

“We got together for a cup of tea,” laughs Fry, who explains that he and Flowers had played on Williams’ 1971 album Changes. Meanwhile, Monkman joined the trio for Williams’ 1978 album Travelling, after which, following a call to Peek, the inevitable happened.

By the time you’re done, you might have got a few hundred quid for a tour. But I didn’t do it for the money

“There was the thinking, ‘Wouldn’t it be lovely to be in a band and have all those lovely things that happen on tour?’” Fry says. “It was the best thing that ever happened to me."

And it all happened very fast – in Flowers’ words, “Suddenly it all went crash, bang, wallop” – from forming, to securing a record deal, to recording the first album at Abbey Road. “I remember when that first album came out and Toccata became a hit, I said to my wife, ‘This band is going to be big!’ Of course, the reality is, if you divide it by five – or six, if you include the manager – then allow for all the other deductions, by the time you’re done, you might have got a few hundred quid for a tour. But I didn’t do it for the money.”

At the height of disco and new wave, Sky were a band out of time, but as the success of that debut proved (it very quickly went gold), their brand of consummate musicianship and quirky diversity was welcomed by the public.

“We were lucky,” contends Fry. “It suddenly took off and we became very successful, perhaps because we were so off the wall. Not as off the wall as the punks, but we were certainly different. It was incredibly exciting because we were coming from every angle, and we all had such diverse backgrounds. John was a classical guitarist, Francis was a great rocker who could play the harpsichord, we had Kevin, who was a wonderful, moving classical and rock guitarist, which not too many can do – it was amazing.”

For Sky’s debut, the record label dreamed up a blurb that took hype to new levels: “Five of the most respected musicians on Earth are in Sky,” it read. “A group of people that talented can’t be bound by an earth-bound name. Sky. The band. The album. Reach for it.”

“Golly,” is Fry’s response to Ariola’s promotional gambit. He was just delighted that Sky’s music “captured people’s imagination, which you wouldn’t imagine such a diverse thing would do.” He remembers it taking all of “three or four months” before Sky caught on, helped by Williams’ already high profile. Fry recalls that he enjoyed the varied nature of their audience.

We told Rick Wakeman: ‘We just want three hours without any jokes!’ We couldn’t laugh any more, otherwise we were going to start feeling ill

“It was very mixed – we could get some lovely nuns as well as rockers,” he chuckles. Nuns? “Yes. Quite surprising, isn’t it?”

What was it like on the road with Sky – heads down, no nonsense? “No, we had an absolute ball; it was such fun,” says Fry, who recalls on-tour high jinks such as the time his bandmates put a body in his bed. “It wasn’t a real body, I have to tell you, it was just a bunch of cushions, but it was pretty scary, getting back very late at night to my room to find what seemed to be somebody in my bed. And they trashed… well, not trashed, but made it look like somebody had drunkenly come into my room and used it.

“So the next morning I very naughtily hid my suitcase and said it had been stolen. ‘But don’t worry, I’ve called the police, they’re on their way.’ That put the wind up the boys a bit!” Then there was the time Sky performed a concert on behalf of Amnesty International at Westminster Abbey – the only instance of the hall being used for such a purpose.

“That was fantastic,” recalls Fry, “although halfway through, the stage underneath the keyboard started to collapse and the roadies, bless them, lay on their backs and held it up with their feet to keep it going, for about an hour.”

Flowers has equally fond memories of the landmark gig. “When the trucks rolled up and set up all their clobber and the dry ice started and everything, the Dean of Westminster said, ‘It’s like the Second Coming!’” he recalls, although he wasn’t impressed with Peek’s choice of outfit. “I was very disappointed that Kevin wore jeans. Not that I’m very religious, but come on. Not at Westminster Abbey.”

What did the bassist wear? “A blue and orange jumper that my mum knitted for me.”

Sky weren’t the serious, solemn musos that they might have seemed then. “I don’t think so,” says Fry, repeating: “We were just lucky. Lucky is the word.”

They were also prolific and, according to Flowers, that might have undermined them, sales-wise. There was simply too much product: seven albums in eight years, culminating in 1987’s Mozart, their most successful album in the States. In between, there were various line-up changes, with Monkman leaving and Steve Gray (session player for Quincy Jones, John Barry and more) replacing him on keyboards. Rick Wakeman even joined for Sky’s 1984 tour of Australia, which pleased the others, even if they did have to relegate him to the back of the plane. Why? Because he was too funny.

“We said, ‘Rick, we just want three hours from Perth to Sydney without any jokes!’” reminisces Fry. “We couldn’t laugh any more, otherwise we were going to start feeling ill.”

Thereafter, there were stints from Paul Hart (keyboards, guitar, mandolin, cello) and Richard Durrant (lead guitar), before the band’s dissolution in 1995. Flowers enjoyed the final few years arguably more than he did the early ones.

“When Steve took over, that opened the door a bit for a little jazz lilt to the music,” he says. “And that gave me a bit more authority to ask someone like Paul Hart – one of the world’s great jingle writers and violin players – to join. The last two or three years were more for the sheer joy of being in that fantastic band. We were still filling out places but I think we knew it would fizzle out and we nipped it in the bud before it did.”

Of the original five, Peek died in 2013, while Gray passed away in 2008 [and Monkman died in 2023]. Nevertheless, Fry doesn’t believe a reunion is out of the question, especially since, as he says, “I don’t feel as though we took it as far as we could. It would be a bit difficult, but that’s not to say it wouldn’t happen. I’d love to, and I know Herbie would too.”

I get lots of kids and young musicians who say, ‘Because of Tuba Smarties I’m now in the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra’

Fry believes Sky occupy a unique position in the affections of the British public, and has nothing but good memories of the experience, and of audiences’ reactions. “It was amazing, this flood of stuff coming from the audience,” he marvels. “I found that very satisfying.”

Flowers, despite being, as he insists, “detached from the cult of personality,” regularly gets accosted by fans of the band when he’s out and about. “I get stopped in Waitrose very regularly from people saying, ‘God, I really like Sky’ – and it’s not always oldies. I get lots of kids and young musicians who say, ‘Because of Tuba Smarties I’m now in the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra.’ It’s quite an honour.”

Then he starts thinking again about the prospect of Sky reforming, and the man, who clearly doesn’t own any rose-tinted spectacles, gets on an amusing roll.

“It’s like when they ask, ‘Are Oasis going to do Glastonbury?’ I think, ‘Bollocks!’ What an awful band. I just read in The Guardian what John Lydon said about the dumbing down of everything. I agree. I mean, what are U2 doing? Suddenly my iTunes memory is full up with free stuff they’re giving away. How dare they?

“Sky were great at the time, but we all change. If I heard something [of theirs] I’d be like, ‘Oh no, God, I didn’t realise it was that bad!’ It’s like Fawlty Towers – awful! Benny Hill – shite! Monty Python – what? It’s like that with a lot of music. Just dreadful.”