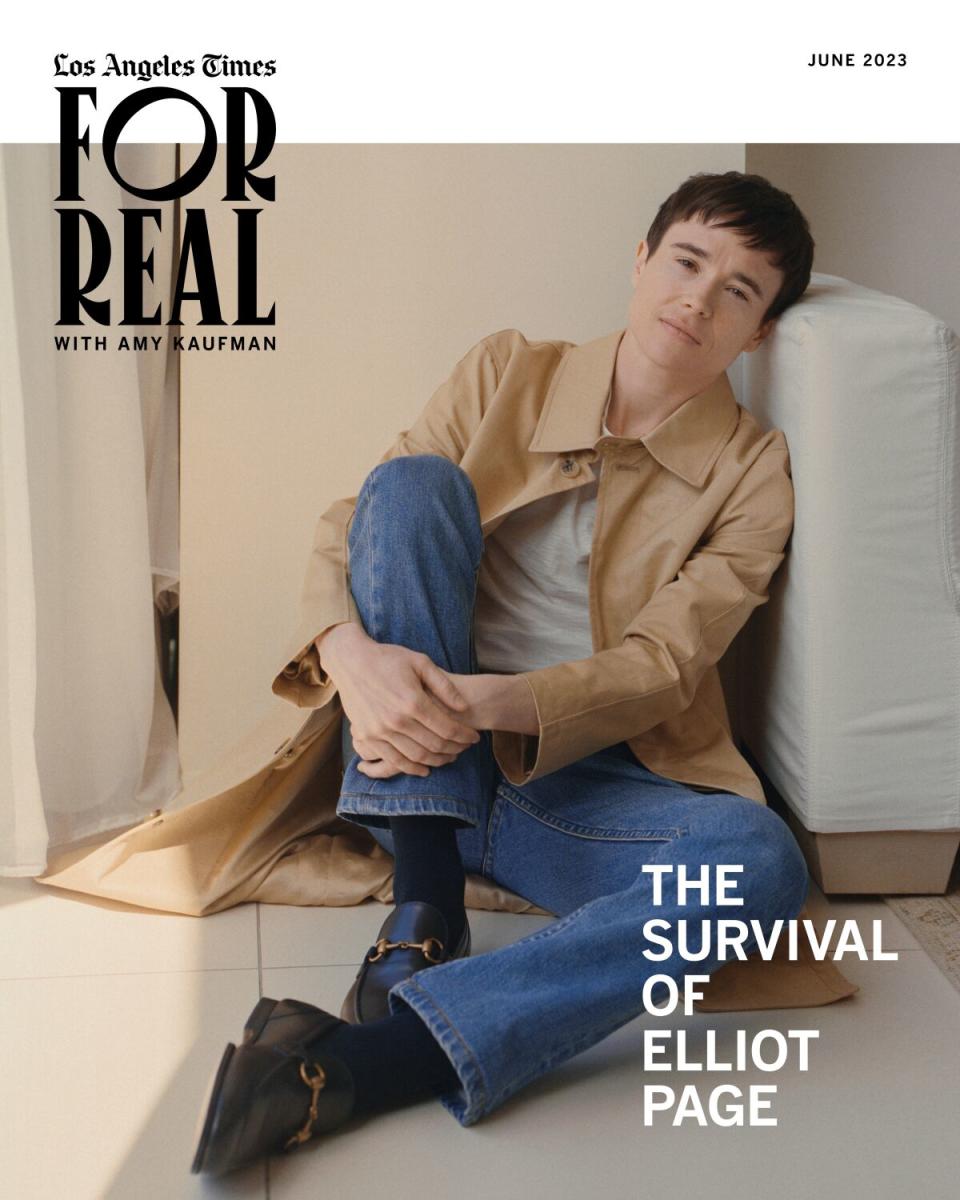

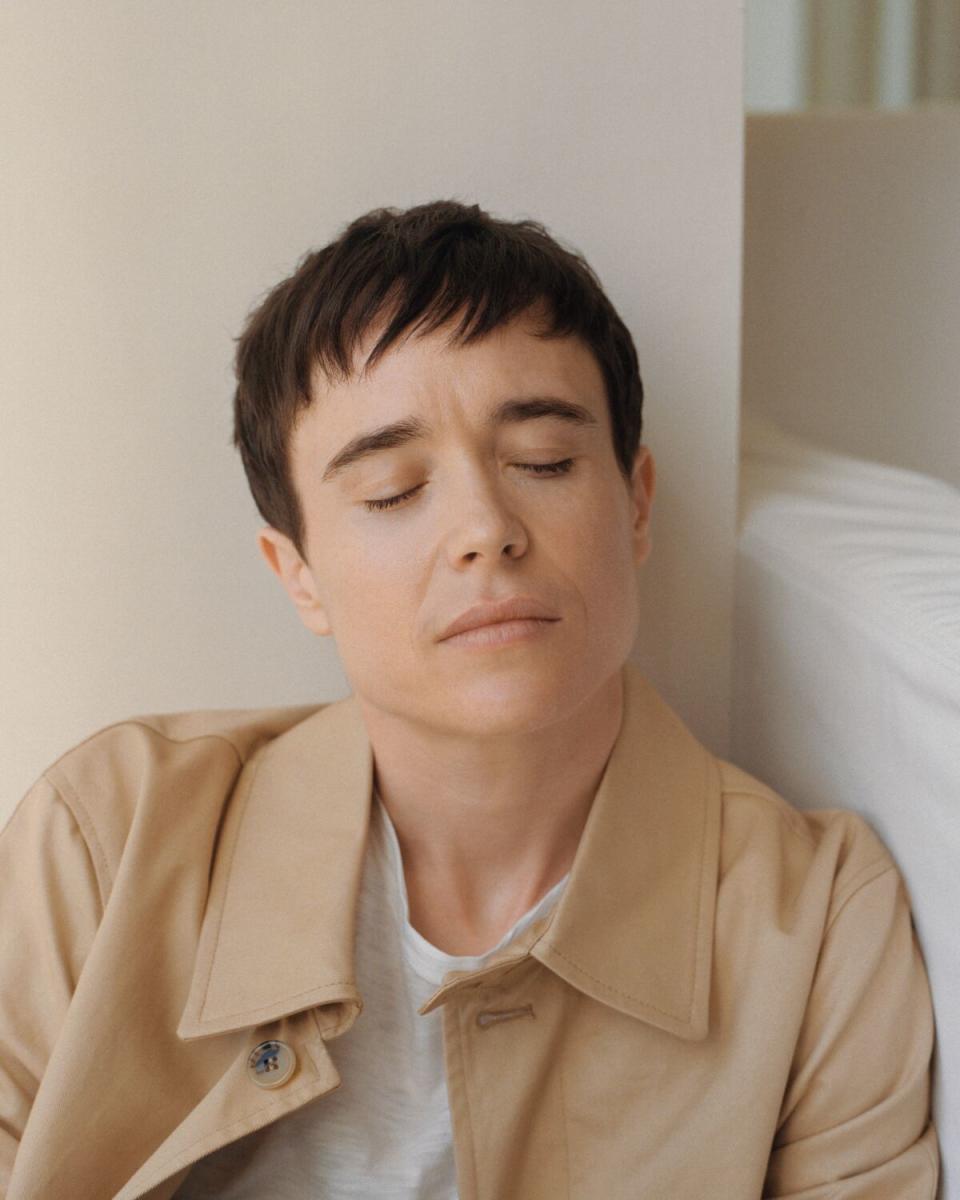

The survival of Elliot Page

All was calm there, deep in the woods of Nova Scotia, but Elliot Page could not find peace.

He’d withdrawn to a remote cabin hoping it would serve as a balm. He and his wife had separated, and he’d given up his apartment in New York City. Then a friend offered up their sparsely furnished retreat in the Canadian forest. It was 2020, the height of the pandemic. The border was shut, but he was a citizen, born in Halifax. So he drove.

It was an extraordinary place, the cabin. Down a dirt road familiar only to wildlife. Pears and apples from an abandoned orchard littered the grounds. But alone in the stillness, Page started to crack. All of the self-hatred he’d been pushing down for years — the discomfort he felt in his body, the anger toward those who’d told him to repress his identity — spilled out.

One night, he tried to knock himself out. Took his knuckles to his face and pounded over and over until bruises formed. For days after, he sat in a lawn chair on the porch, ashamed, his face sore. And then he heard a voice.

“You don’t have to feel this way.”

It was a small voice, barely discernible. But it kept echoing in his head. A way out.

“It was as if something in my brain turned around,” recalls Page, now 36. “The agonizing voice saying, ‘No, you’re not,’ ‘No, you can’t’ just switched and became very gentle and loving. ‘Oh, maybe I’m trans. Why don’t I explore that?’”

Within weeks, he’d scheduled a Zoom consultation with a doctor to discuss top surgery. The procedure was scheduled for November. A month later, he announced to fans on Instagram, who have known him since the release of "Juno" 13 years prior, that his name was Elliot.

The writers of “The Umbrella Academy,” the Netflix superhero series on which he’d played a female character for two seasons, immediately began rewriting the role to make him trans. After shooting the third installment of the show in early 2021, Page sat down with Oprah Winfrey to discuss his transition.

Within a span of a few months, he had become the most famous transgender man in the world.

And there was so much joy. In his new body, which he shared for the first time online, grinning in a pair of swim trunks. He presented at the Oscars in his outfit of choice, a tuxedo. Casting directors reached out in droves, saying they’d love to work with him. His mind clear of distressing thoughts, he regained his ability to focus while reading. He even decided to write a book of his own, “Pageboy,” a memoir in which he reckons with his journey to self-acceptance. Raw, harrowing and often heartbreaking to read, it comes out this week.

But there has also been this weight. The constant reminder that the vast majority of trans people face a reality drastically different from his own. When asked to pose for a magazine cover under a headline about his “euphoria,” Page wants to take the opportunity. Because representation makes a difference. But there’s also this worry, he says, that the glossy pictures “allow people to go, ‘Oh, well, look. They’re fine.’”

But trans people are not fine. Page's book arrives, as if on cue, in a moment when the trans community is facing even more danger than when he started writing it just over a year ago.

In the U.S., Republicans have ramped up efforts to establish anti-trans bills on the state level. Nineteen states — including Florida, Arizona and Tennessee — have enacted laws or policies banning gender-affirming care for minors. Legislation has also targeted young trans athletes participating in school sports and trans people in gender-segregated spaces like restrooms and locker rooms.

As he prepares for the 2024 presidential election, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis has enforced many of these issues — even signing a bill last month restricting preferred pronouns from being discussed in schools. Former President Trump, meanwhile, has referred to gender-affirming care for those under 18 as “child sexual mutilation” and “child abuse.”

Page's visibility means that he — a man who wears Nike shoes from the boys section because the ones in the adult department are too large for his feet — shoulders the weight of a roiling, often very ugly cultural conversation.

“I'm such a rare example of what it means to be trans,” Page says. “I'm just in this strange position where it's like, yeah, my journey has really not been easy. At moments, I thought: ‘I don't know what my future is. I don't know if I see it.’ But I also just have this amount of privilege that so many trans people do not get.”

And yet here, downstairs at his Sunset Strip hotel, he is less than a mile from the spot where a man on the street threatened to assault him just last year. As he describes in his book, Page, who lives in New York, was standing at the corner of Sunset and La Cienega, taking a quick walk to the Pink Dot convenience store, when a stranger approached.

“I’m going to f—ing gay bash you, faggot,” the man threatened. Terrified, Page began running toward the Pink Dot, where employees ushered him inside. From the other side of the door, the man yelled: “This is why I need a gun!”

“Now when I’m in Los Angeles, I don’t feel comfortable like I used to going for walks,” Page says.

How this man — the one who has just speed-walked apologetically to greet me, even though we are both early — inspires such vitriol is difficult to metabolize. This man whose emails are filled with the phrase “No worries if … .” This man who can barely go a sentence without bringing attention to those who have it worse than him.

Even after the Pink Dot incident, he had a fancy hotel room to go back to, he says. Should he have a significant safety risk like a death threat, he can afford to hire security.

“Doesn’t mean it’s not traumatic,” Page says. “But I have resources that, in every instance that is difficult, protect and can shield me from these things.”

But it’s taken years for Page to even acknowledge that he’s experienced severe mental and physical anguish. When he started going to therapy at 23, the analyst responded to the stories from his upbringing by telling him he’d “had a fair amount of trauma.”

“Trauma?” Page says he responded. “What are you talking about? I haven’t had trauma.”

But in writing “Pageboy" — which he did himself, eschewing a ghostwriter — he for the first time grasped the totality of what he’d been through. It was helpful, he says, realizing: “Jeez, Elliot, this was a lot.” And that in excavating his past, he was able to confirm just how long he’d struggled with his gender identity.

Since age 4, when in the bathroom at his YMCA preschool he tried to pee while standing up. At age 6, asking his mom if he could be a boy.

As a kid, he hid out in his room playing with Batman and Robin action figures and Barbies from Happy Meals whose hair he had chopped off. In the imaginary love letters he wrote to a fake girlfriend, signed, “Love, Jason.”

“That private play let me experience a gender euphoria, because I wasn’t being seen by anyone else,” he says. “I was just in my own world as the boy that I was. It was crystal clear to me.”

But growing up in Halifax in the ’90s, Page had no examples of what it meant to be transgender. He didn’t even learn the word until he was a senior in high school.

When he started to explore the idea that he might be gay, his family was not accepting. His mother, a minister’s daughter, told her son that homosexuality didn’t exist. When he started acting as a teenager, he once had to shave his head for a role; his grandmother responded to the look by asking Page’s father what he would do if his daughter was a "dyke."

At 16, Page’s dysphoria began manifesting in self-destructive behavior. He restricted his calories. Smashed his head with a hairbrush. Cut his shoulder with a knife. Hoisted his body onto the spike of his mother’s bed frame in an effort to impale himself.

Writing about all of this was hard. Often, he’d start to sweat profusely. But he forced himself to stick to a strict routine. Wake up at 5:30 a.m. Write for two hours. Walk the dog. Write for a couple more hours. Eat lunch, maybe work out. Return to the desk until 4 p.m.

It was necessary, he says, to meet his deadline, turning in 5,000 words to his editor, Bryn Clark, every Wednesday.

Clark, an executive editor at Flatiron Books, had been chasing a book by Page since 2019. That’s when she slid into his Instagram DMs to ask if he was open to writing. The message went unread, but when Page sent out a proposal in February 2022, Clark made sure her company was ready to make an offer.

“I’d always had that feeling that he had a book to write, and not just any book, but a book that could have the ability to move the needle in a much needed way right now in our society,” says Clark, who worked at the Massachusetts Transgender Political Coalition before getting into publishing.

“Pageboy” also offers stark insights about how Page was treated by Hollywood.

After working steadily as a young performer in Canada, he became known to American audiences first as a vigilante stalking a sexual predator in the 2005 film "Hard Candy" and then, more widely, in 2007’s “Juno.” In the latter film, written by Diablo Cody, Page played a wisecracking teenager who finds out she’s pregnant and then develops an unusual relationship with the couple she plans to let adopt her child. The role earned Page an Oscar nomination and led to a near-unified sense that he was a performer to watch; he went on to secure parts in movies like “Inception,” “Whip It” and the “X-Men” franchise.

Even though he had to wear a fake belly in “Juno,” Page felt more at ease in the film than many of the dozens of others in which he starred. He liked that Juno wasn’t hyper-feminized, that the producers let him pick out the character’s wardrobe — hoodies, flannels, baggy jeans — at used clothing stores in Vancouver.

“How she dresses really resonated with people, I think, particularly young women who were constantly seeing something else at the time,” says Page. “What’s so unfortunate and gross is that the people who were profiting massively off of the movie squashed that part of what made it so special by telling me to promote it while wearing dresses and heels.”

In his memoir, Page writes about how he wanted to wear jeans and a western shirt to the film’s premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. But the publicity team at Fox Searchlight rejected the idea, rushing him to a local department store to find something they deemed more feminine. Jason Reitman, the film’s director, “insisted that I play the part,” Page writes, though he notes that the filmmaker has since apologized.

“Michael Cera rocked sneakers, slacks, and a collared shirt. He looked fancy to me,” Page writes of his co-star in the film. “I wonder why they didn’t take him to Holt Renfrew. I guess he had nothing to hide, he was approved. He fit the part.”

A few months later, at the 2008 Academy Awards, Page was even more uncomfortable. He was dating a woman at the time but had been urged by his manager to hide this relationship from the press, so he did not have his partner by his side.

It would be six more years before Page came out as queer in a speech at a Human Rights Campaign event.

“Clearly that wasn’t ultimately where I needed to get to, but it was a massive step forward and a whole bucket of bricks off my shoulders, honestly, overnight,” Page says. “It wasn’t that I was thinking, ‘Oh, I’m trans, but that’s too much.’ Feeling significantly clearer about that came later.”

Still, Page faced discrimination from his industry peers. Once, while doing a screen test at a studio, he was asked to wear hair extensions because executives thought longer locks would make him look “more soft.” While making 2017’s “Flatliners,” Page asked that his character not wear a skirt; a member of the production team asked him: “Are you mad that this character isn’t gay?"

But perhaps most vile is the story he recounts in the chapter "Famous Asshole at Party." In 2014, Page writes, a man who “was and still is one of the most famous actors in the world,” approached him at a Hollywood house party and hissed: “I’m going to f — you to make you realize you aren’t gay," the star said, going on to graphically describe a sexual act he planned to perform on Page.

Page says he decided not to name-check the actor because he didn’t want the story to turn into a media frenzy in which clickbait eclipses the actual conversation. But he’s not afraid to call people out. In 2017, he wrote in a Facebook post that the director Brett Ratner had outed him as gay and sexually harassed him on the set of 2006’s “X-Men: The Last Stand.”

In that same message, Page revealed that when he was 16, he was propositioned by a director and sexually assaulted by a grip — abuse that did not stem from his gender or sexual identity.

He thought it was important to share more about these instances in “Pageboy” because he found himself frozen in the midst of these assaults — an experience “that’s so prevalent and insidious that it really stays with you.”

He froze when, at 17, a man who’d worked on “Hard Candy” took him back to the Oakwood Apartments, laid him down, removed his pants and expressed a desire to give him oral sex. He froze when a crew member on another film took him to look for a place to live and, during the tour, suddenly started kissing and dry humping him.

“I didn’t say no, I did not resist, I just stiffened,” Page writes.

“That behavior was happening on sets when I was so young that you don’t talk about it,” Page says now. “I used to just shove it away. Like, ‘Oh, what are you complaining about? It’s no big deal.’ It took time to go, ‘Oh, wow, that actually caused damage.’”

Eventually, the trauma — compounded by his unease in his own skin — caught up with him. By his late 20s, he was racked with anxiety. He dove into relationships, clinging to partners in the hope that love might provide him solace. But he wasn’t choosing people who were emotionally available. At one point, he began dating the actor Kate Mara while Mara was in a relationship with Max Minghella. Minghella gave Mara his blessing to explore her connection with Page, but ultimately Page was unable to handle Mara being in love with him and someone else.

He started to back out of important obligations. Sometimes, he’d be on his way to a meeting, start panicking and have to turn around. And his colleagues weren’t always understanding.

“They’d be like, ‘Well, part of the reason the film is at that festival is because you said you’d go,’” Page recalls. “I can imagine people being, like, ‘God, get over yourself. Pull it together.’”

He’d watch his friends tackle daily tasks with aplomb and grow baffled by their ability to self-discipline. “What do you do when you wake up in the morning?” he once asked an ex. Because he couldn’t just wake up and sit with a cup of coffee, read for a bit, start work.

“It felt like crawling,” he says. “I guess that’s probably what depression is.”

He thought that coming out as queer would be the solution. He finally felt emboldened to go out, socialize with others in the LGBTQ+ community. But when he did, he felt so disconnected that it actually made him feel worse. The things his peers found relaxing — sunbathing, lying on the beach — filled him with dread. “I need to get out,” went the refrain in his head. But no. Because it was too big. He was too well-known to transition in public. “You just need to learn to be comfortable,” he urged himself. “You’re fine.”

And then the cabin. That lightning bolt of clarity. He knew he needed to act before the electricity left his body.

He had three months until the third season of “The Umbrella Academy” was set to start shooting in January 2021. Steve Blackman, the showrunner, was one of the first people Page told about his plan to get top surgery. The show creator said he wanted to support Page by also making his character trans, and said he would get the wheels moving while the actor recovered from his procedure.

On Nov. 17, 2020, Page paid $12,000 out-of-pocket for his surgery at a clinic in Canada. His childhood friend Mark Rendall volunteered to help him during recovery, when Page was often emotionally overwhelmed.

“It was really intense for him at that time,” says Rendall. “I don't know if it was regret about not having done it sooner or having felt this way for so long. But there was a process of mourning for what could have been — for all the years that he held things in and felt like he couldn’t express himself.”

And then, as soon as he had physically recovered, Page had to jump into production. Blackman hired Thomas Page McBee, a trans man who’d worked with Page on 2019’s “Tales of the City,” to help rewrite “The Umbrella Academy” scripts. McBee let Page guide the experience, basing the new storyline on his conversations with the actor.

“His performance just felt like it was an opening up,” says McBee. “There's so much light and kind of joy that comes through. I remember my early transition was such an excruciatingly vulnerable time. I definitely, like many trans people, did not want to be visible in any way in that period. So I thought that was incredibly brave of Elliot.”

Last month, Page wrapped filming on the fourth and final season of the show. After our first meeting in L.A. in April, he flew back to Toronto for his final weeks in production.

“I just feel so much better on set,” Page says, video chatting from his rental apartment during a weekend off. “More centered. More patient. There’s an ability to enjoy the work that I haven’t felt for a very, very long time.”

Page hasn’t acted in any project other than “The Umbrella Academy” since coming out as trans, largely because all of his free time in 2022 was devoted to writing “Pageboy.” But moving forward, he’s open to playing both cisgender male and trans roles — though the latter excites him more.

“I want to play queer characters. Like, why would I not? I’ve been playing all the other ones,” he says, noting that he has two projects lined up in which he’ll portray trans men. “That’s what I want to do. That’s who I am, and we need those stories.”

He’s also trying a new approach to dating. After years of being codependent, Page says he’s joined some dating apps and is resisting the urge to jump into relationships.

“It’s the most fun I’ve ever had dating,” he says. “Interacting with people feels so much easier and more connected, because I'm not feeling lost in myself and not seen in the right way. … In the past, I always had an intense crush or fixated on an ex. Right now, there’s none of that. Like, ‘Whoa, I’m alone, and it feels really good.’”

He is open to getting married again. (His first marriage, to dancer-choreographer Emma Portner, lasted from 2018 to 2021.) But he doesn’t know if he wants kids — at least not “ones of my own, like, a baby and that whole thing. But in the future, who knows? I’d adopt someone who is older and needs a home and someone to love them.”

Family is a tender spot for Page. After years of resisting her son’s identity, Page’s mother has finally come to accept him. It was almost as if she experienced a sense of relief when Page came out as trans, he says, because she was able to watch him at ease with himself. She still expresses guilt to Page about her past intolerance, but Page says he’s forgiven her. “I think it’s really inspiring that she’s changed and become such an advocate and ally,” he says. “It took her time to break out of the ideas she grew up with.”

His father, however, is a different story. Page declines to speak about their relationship, but in his book, he writes that he and his dad haven’t communicated in 5? years — and he can’t envision them ever talking again. Much of the strain has to do with the fact that his dad supports “those with massive platforms who have attacked and ridiculed me on a global scale,” Page writes.

“When [right-wing author] Jordan Peterson was let back on Twitter after he’d made a horrific tweet about me, he posted a video, just his head filling the frame. Staring menacingly into the camera, he said, ‘We’ll see who cancels who.’ My dad ‘liked’ it.”

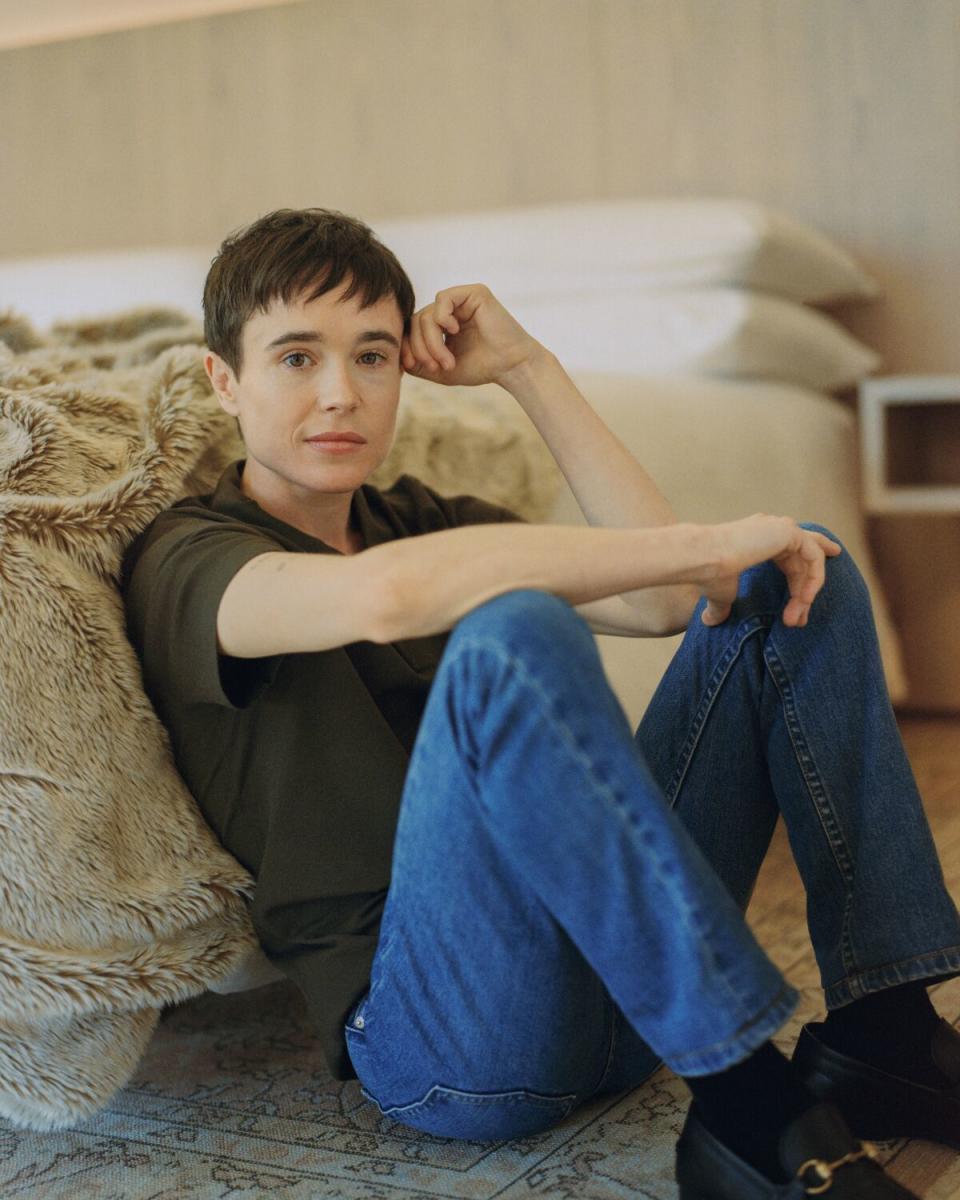

Despite Peterson’s rants about Page daring to share shirtless pictures of himself, Page says he’s feeling more confident than ever in his body. He’s obsessed with "Supernatural," a virtual reality fitness game that allows users to do cardio or boxing while in a Norwegian fjord or on the surface of Mars. He loves how strong his body has become, and he also likes how it looks. During photo shoots, he used to catch a glimpse of himself in a monitor and start to spiral. Now, he says, his publicist will share some images and his first thought is: “Oh, that’s kind of cool. He’s kinda cute.”

“There was this heavy presence — almost like a ghost — that existed prior to him coming out and now it’s not there,” says Rendall, his longtime friend. “It’s like, ‘Oh, hello. There you are. There you are without all of this unnameable pain.’ It’s beautiful, seeing someone have liberation from that specter unnamed."

Part of that liberation, Page says, came with writing his memoir. He found the experience cathartic and says it’s helped to heal many relationships in his life. Clark, his editor, believes the book has the ability to bring the transgender struggle to a human-size scale.

“This is an insider view into somebody's thoughts about what it is like to navigate a society that's constantly telling all of us who we're supposed to be — and what the cost is if we are not that person,” says Clark.

Which is not to say that Page is suddenly living some perfect, pain-free life. He is not, as he says, “singing in a meadow” every day. A lot of what dogged him before, including his persistent anxiety, is still part of his makeup. It’s just that now, there’s more space. Room to think about who he can be now that he’s allowed Elliot Page to exist.

When he used to take his rescue dog, Mo, on walks to the park, he was never present, he says. He’d check his watch to see how long he’d been gone. Start thinking about what he wanted for dinner and then decide he shouldn’t eat that. Check his reflection in passing windows to see if he could flatten his chest further.

“Now, you’re walking, and the leaves are so f—ing green,” he says. “The sounds of the birds make you melt. The air on your skin — the beauty just blows you over. You’re fully embracing the sensation of being alive.”

L.A. Times Book Club: Elliot Page

What: Elliot Page will be in conversation with Kate Mara about “Pageboy” at the L.A. Times Book Club.

When: June 8 at 7 p.m. Pacific.

Where: The Montalban Theatre in Hollywood. Get tickets.

Join us: Sign up for the Book Club newsletter for the latest events, books and news.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.