“To survive in this game, we had to get away from the 10-minute guitar solos”: the story of .38 Special, Blackfoot and the Southern Rock/AOR crossover

While punk rock was rearing its ugly head and usurping the UK charts back in 1976, something more interesting was happening across the pond: Adult Oriented Rock was dominating the American singles charts.

Bands like Aerosmith (Dream On), Boston (More Than A Feeling), Eagles (Take It To The Limit), Kiss (Beth), Heart (Crazy On You), The Doobie Brothers (Takin’ It To The Streets) Steve Miller (Rock’N’Me) and Blue ?yster Cult (Don’t Fear The Reaper) all showed just how rich in talent the American airwaves had become.

But one genre was, mysteriously, missing…

Lurking just beneath the surface and itching to break into the AOR Premier League was a form of music simply known as southern rock. With its rootsy bluegrass, cajun fiddles and never-ending duelling guitar solos, this form of music was unlikely to find itself lurking in the higher reaches of the American Top 40.

Something had to change; enter one Rodney Mills. In 1970, Rodders was approached by the renowned American songwriter Buddy Buie (who has penned compositions for the likes of Roy Orbison, Carlos Santana and Gloria Estefan) to build him a brand new, state-of-the-art recording studio in Doraville, a suburb of Atlanta, and become the house engineer of what was to become the legendary Studio One. Now, some 40 years on, and with more than 50 gold and platinum albums to his name, Mills is the man to thank for southern rock making the successful transition from FM to AM radio and the American AOR Top 40.

One of the first bands to make this successful crossover were The Atlanta Rhythm Section (later to be known simply as ARS). They started out as the house session band for Studio One; however, with Buddy Buie behind the band, they were soon picked up by MCA/Decca Records. Their first, self-titled album, released in late 1972, received critical acclaim, but the band were mocked for not having paid their dues on the road. It was not until their third outing, 1974’s Third Annual Pipe Dream, that things began to take off. The band scored their first Top 40 hit with Doraville, an uptempo rocker with the memorable hook line: ‘Doraville, a touch of country in the city/New York’s fine, but it ain’t Doraville.’

With their new, more radio-friendly sound, ARS went from strength to strength. Dog Days (1975) was their most adventurous album to date, but it was Red Tape (1976) that took the band forward. The songs were now shorter, sharper and a lot more radio-friendly, but Polydor wanted a big hit, so ARS recorded A Rock And Roll Alternative in a mere 30 days (quite a feat back then), engineered by Rodney Mills and produced by Buddy Buie. The album had a real laid-back feel about, it and they scored their first Top 10 hit with So Into You, a delightful ballad with a Toto feel about it. The album, meanwhile, broke into Billboard Top 10 and eventually went gold.

Other southern rock bands soon started to pick up on the success of ARS’s mammoth leap into AOR heaven. Almost apologetically, combos like The Outlaws and The Marshall Tucker Band began creeping into the singles charts. The former had moderate chart success with a cover of (Ghost) Riders In The Sky, which broke into the Top 30, while the latter climbed to No.14 with the goose-bumpin’ Heard It In A Love Song, lifted from 1977 platinum-seller Carolina Dreams.

As the 70s gave way to the 80s, more and more southern bands were making successful transitions into the kingdom of AOR. Let me now introduce you to Thunder. Not to be confused with the chirpy Cockneys, this American band released two very accessible albums via the Atco label, the pick of the crop being the amusingly titled Headphones For Cows. A few southern moments do creep in, but it’s mainly an AOR delight. It opens with Can’t Hold On, Can’t Let Go, a midtempo rocker with more than a nod to Toto, while Tupelo, with its smooth duelling guitars and harmonies, is very reminiscent of the Doobie Brothers.

Despite the obvious quality of the musicianship, Atco never really got behind the band and they swiftly disappeared into the cut-out bins. Thankfully, though, Headphones For Cows was recently picked up by Wounded Bird Records and is available again.

Lynyrd Skynyrd, for the main part, never really needed to venture into AOR territory, so strong was their repertoire. However, it was a different story for the various Skynyrd offshoots. The Rossington/Collins band, rising from the ashes of the Skynyrd plane crash, were formed by former Skynyrd guitarists Garry Rossington and Allen Collins, and were considered to be a more subtle and mellow version of Skynyrd. Their debut album Anytime, Anyplace, Anywhere (1980) spent months in the Billboard Top 100 and spawned a hit with the infectious Don’t Misunderstand Me which peaked at No.9 in the singles chart. Sadly, a lacklustre second outing, This Is The Way (1981), was not helped by the death of Allen Collins’ wife, which drove poor Allen into a downward spiral of Jack Daniel’s and the subsequent demise of RCB.

Drummer Artimus Pyle, meanwhile, whose injuries from the plane crash prevented him joining The Rossington Collins Band, had fully recovered by 1982. He put together APB (Artimus Pyle Band), who recorded two albums for MCA. APB (1982), their debut, was pretty straightforward southern fare, with cuts like It Ain’t The Whiskey and Rock & Roll Each Other. However, 1983’s Nightcaller signalled a most welcome change in direction, inviting Toto’s David Paich and Steve Porcaro on board, along with vocalist Karen Blackmon, who took APB deep into AOR territory. Her soothing voice was especially potent on Hoping I’ll Find You and Only Child, which almost sound like Heart.

Johnny Van Zant was also getting in on the act, recording a number of AOR-influenced solo albums before becoming the new frontman of the revamped Lynyrd Skynyrd in 1987. Produced by the legendry Al Kooper, 1980’s No More Dirty gets softer as it progresses; 634 5789 has an almost pop feel to it, while Hard Luck Story is dominated by keyboards, with the guitars being held way back in the mix. Brickyard Road (1990) carries on the soft rock theme: the title track was No.1 for three weeks on the Billboard Mainstream Rock Tracks chart), while Bad 4 U deftly betrayed the influence of Foreigner.

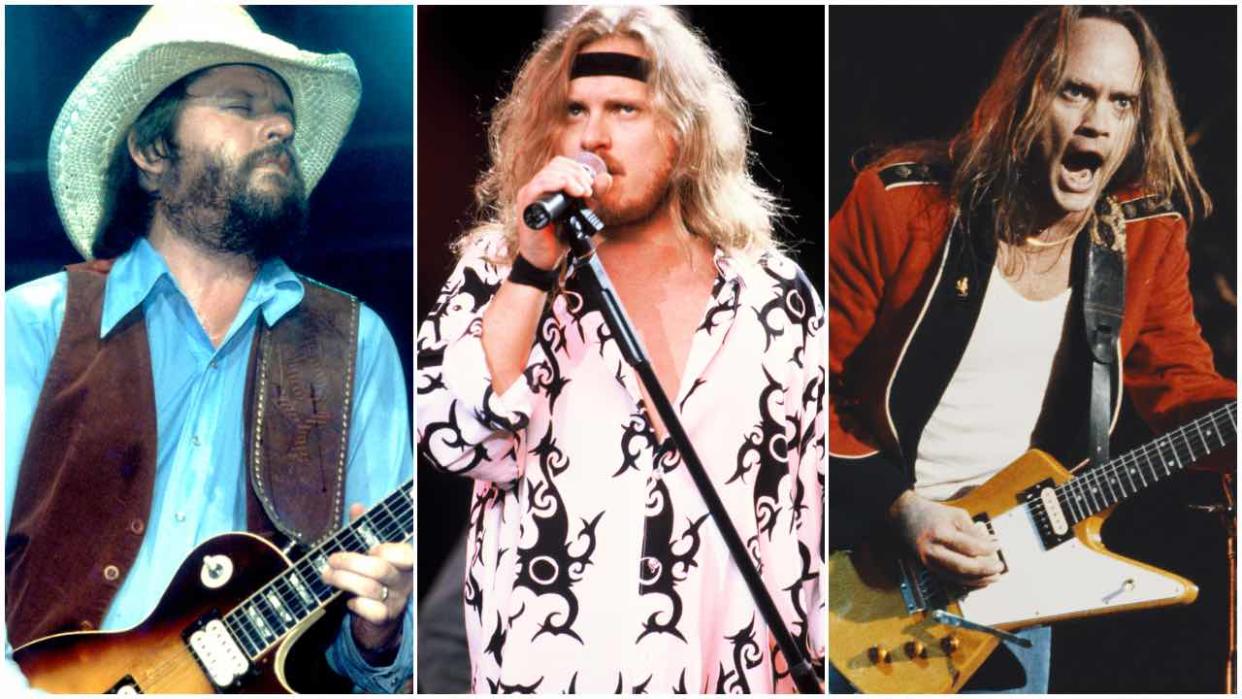

The Skynyrd connection continues with .38 Special and yet another Van Zant brother, Donnie. .38 Special were formed in 1975 in Jacksonville, Florida and started out as a straightahead southern rock band. It wasn’t until their third album, 1980’s Rockin’ Into The Night, that they began to make a serious dent in the charts, dropping their southern roots for a more polished and commercial AOR/arena rock sound. With crisp production from Rodney Mills, the leap into the big time arrived with 1981 offering Wild Eyed Southern Boys, which was later to go platinum. Opening track Hold On Loosely is a perfect example of classic duelling guitars, Don Barnes and Jeff Carlisi churning out heavy yet catchy riffs that gel perfectly with Donnie Van Zant’s voice and backing harmonies. The song is heavy as hell, yet feels and sounds incredibly commercial – which could explain why it climbed to No.27 in the US. Other delights from this flawless classic include First Time Around, with its nifty hooks and cool harmonies, and Fantasy Girl, again very upbeat and commercial.

38. Special’s next outing, Special Forces, again went platinum and spawned another hit single, Caught Up In You, which peaked at No.10. I first met the band as they were promoting their 1986 release Strength In Numbers, which eventually went gold. I recall spending a very pleasant day in the company of guitarist Jeff Carlisi, who showed me all the finest southern rock hangouts in Atlanta, Georgia.

“After our first two albums we found ourselves gradually moving away from typical southern rock, to a more polished and commercial sound,” Jeff explained that afternoon, of .38 Special’s enduring success. “Myself and the guys would just keep coming up with catchy hooks and good harmonies, songs we knew that would attract radio airplay. We knew that to survive in this game, we had to get away from 10-minute guitar solos. Most of the songs on Strength In Numbers run below four minutes, and producer Keith Olsen managed to keep the sound crisp and sharp.”

.38 Special scored their biggest hit with 1989’s ballad Second Chance – a song Jeff Carlisi had penned five years earlier and shelved – which peaked at No.6 in the Billboard Hot 100. .38 Special are still very much around, touring the US in 2009 on a bill that included Styx and REO Speedwagon.

No southern rock article would be complete without a nod to ZZ Top. Early albums like Tres Hombres, Fandango! and Tejas were deeply rooted in their love of blues. But, boy, could they boogie – just listen to La Grange.

So imagine the shock when the Top’s Eliminator album hit the streets in 1983. It was a total departure from everything they had done before. Out went the blues, and in its place came synths, drum machines and an overall more ‘techno’ feel. Indeed, it has been suggested that Billy Gibbons was the only member of the band to actually play on the album. Eliminator was made all the more popular by witty videos accompanying Legs, Gimme All Your Lovin’, Sharp Dressed Man, Got Me Under Pressure and the truly hysterical TV Dinners. ZZ Top would never top the success they achieved with Eliminator, which went diamond in the US, shifting a remarkable 10 million copies.

Meanwhile, Le Roux started life as a Cajun-blues/soft rock outfit but would go on to produce one of the great AOR masterpieces – that’s right, up there with Journey’s Escape. The band formed in 1978 from the ashes of The Jeff Pollard band and took the name Louisana’s Le Roux. A deal with Capitol followed, and their self-titled debut album was a delightful platter of Cajun soft rock, with a blues feel. They scored a minor hit with their southern anthem New Orleans Ladies; meanwhile, 1979 LP Keep The Fire Burnin’ was best remembered for its memorable cover, depicting a businessman having a plate of spaghetti poured on his bonce.

Musically, though, the band were now moving away from their Cajun roots and adopting a more AOR-friendly sound with delightful a cappella harmonies, Call Home The Heart being the pick of the bunch. Now known simply as Le Roux, their 1980 LP Up was recorded at Cherokee Studios in LA; a landmark album, every song a towering monolith of multi-layered harmonies, boasting a beautifully structured use of synthesisers and guitars. There isn’t one duff track on the album.

As main songwriter, guitarist and lead vocalist Jeff Pollard recalled at the time, “Jai [Winding, producer] was able to tap our potential in a new direction. Up is really different in a lot of ways from our first two albums, but it’s still very much Le Roux. I’ve never sung so high and so hard in my life, but it really worked. It wasn’t just getting the notes right, or just the right feeling, it was getting the precision and soul at the same time. For quite a while I’ve had a guitar sound in my head that I’ve never really been able to get on tape – until now. Doing this album was the most creative experience I’ve ever been involved in.”

Despite its brilliance, Up never really took off. Pollard quit the band after their next studio album, Last Safe Place. His replacement was Fergie Frederiksen, who would later join Toto. Fergie made a major contribution to Le Roux’s other AOR classic, So Fired Up (1982). Although not a patch on Up there are still some pretty impressive songs on offer, such as Turning Point, Lifeline and Carrie’s Gone, which became a minor hit and peaked at No.79. Le Roux still tour today and recently played with Styx at New Orleans’ Mardi Gras Ball.

For all the successful crossovers from southern rock to AOR there have been a few that haven’t quite taken. Blackfoot’s Siogo was a prime example of a classic southern rock band being told by their record label (Atco) to make a ‘commercial’ LP. Recorded in 1983, Siogo was rightly ridiculed by southern rock fans; the band recruited former Uriah Heep keyboardist Ken Hensley, and his addition was to prove costly. Siogo sold poorly, and listening to the album again it’s easy to see why. Send Me An Angel, dominated by Hensley’s dated keyboards, is truly hideous, while Goin’ In Circles is a terrible attempt at imitating Rainbow. Run For Cover, with its half-baked harmonies, really comes across as tired and uninspired. Maybe one day Ricky Medlocke could remix the album and take off the keyboards.

Meanwhile, Doc Holliday – a southern rock outfit from Macon, Georgia, named after the famed Wild West gambler and gunfighter – also came under pressure from their record label, A&M, to do something different with their third outing, Modern Medicine. They hired German producer Reinhold Mack, who went by his last name only and had worked with Queen, ELO and Billy Squier. The end result was nothing short of disastrous: techno southern AOR. I kid you not. Mack was not the right producer for this project, as Doc Holliday’s Bruce Brookshire recalled:

“A&M thought it would do us good to get a producer with a good track record. It got to the point in America where getting airplay on the radio was crucial, and we couldn’t get arrested with our music. The charts back then were full of claptrap like Culture Club and Cyndi Lauper. The album was deliberately produced with a poppy edge to it. It was an experiment that sadly failed, and consequently the album didn’t go gold or platinum, in fact it went plywood.”

There’s a track on the album called You Don’t Have To Cry. You will when you hear it. Doc Holliday never really recovered and broke up shortly afterwards, although they did re-form in the 1990s, and are still going today.

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents AOR issue 4