'The Alamo' at 60: What John Wayne's film gets right and wrong about the famous Texas battle

The Battle of the Alamo was fought over 13 days on the grounds of an 18th century Spanish mission in San Antonio in the winter of 1836. But the battle over our collective memory of the Alamo is still being fought today. What unfolded in real time as one front in a regional conflict between Mexico and the nascent Republic of Texas has long since become a national symbol of American heroism and fighting spirit as summed up by the now-famous battle cry: “Remember the Alamo.”

That transformation has been aided in no small part by movies. 1915’s Martyrs of the Alamo was one of the earliest cinematic depictions of the siege — which found a small army of Texians (residents of what was then called Mexican Texas) and famed American frontiersman like James Bowie and Davy Crockett making an ultimately unsuccessful last stand against the forces of Mexican general Antonio López de Santa Anna — and it added a mythic sheen to events that obscured the historical record. Produced by Birth of a Nation director D.W. Griffith, that silent film depicted the Texas side as largely consisting of white soldiers, and also went out of its way to demonize the Mexican troops.

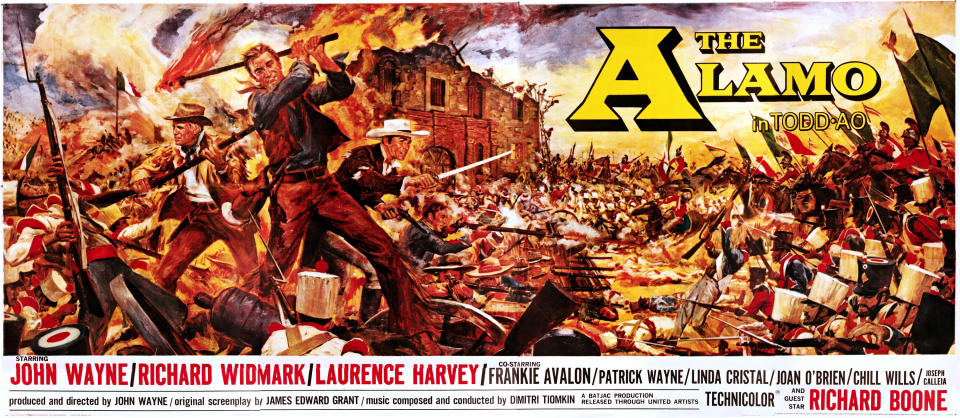

Walt Disney also offered a sanitized version of the battle in its 1954 TV series Davy Crockett (later released as two feature films), which depicted the coonskin cap-wearing pioneer, played by Fess Parker, as making a heroic last stand at the mission. But the Alamo received its grandest stage in John Wayne’s frontier epic The Alamo, which opened in theaters 60 years ago on Oct. 24, 1960. Wayne directed and stars as Crockett in the two-and-a-half hour production, which was fashioned in the mold of the classic Westerns he made with John Ford, including Fort Apache and The Searchers. (In fact, Hollywood legend has it that Ford tried to take control of The Alamo behind the camera when he showed up on set, and Wayne dispatched him to helm second unit footage instead.)

But the famously conservative actor also brought his own specific politics to the story. With the Cold War in full swing, Wayne — who had sided with the forces of McCarthyism during Hollywood’s ’50s-era Red Scare — imbues the movie a pronounced “us vs. them” patriotism, and makes room for pointed asides such as Crockett’s explanation for why he’s so moved by the word “republic.” “It’s one of those words that makes me tight in the throat,” Wayne remarks in the movie. “Some words can make your heart warm: Republic is one of those words.”

At the same time, Wayne is trying to deliver grand spectacle; made for a then super-sized $12 million budget, The Alamo climaxes with an extended large-scale battle sequence that was singled out for praise at the time. It’s also the scene that resonated most with Ernesto Rodriguez, who grew up to become a curator at the real-life Alamo, which has been preserved as a historic site in San Antonio. “It’s a great scene,” Rodriguez tells Yahoo Entertainment. “John Wayne's movie is still a reason why some people come visit the Alamo. They remember watching that movie and it's stuck in their head as a place that they must come visit one day and try to see the place where this battle happened. It’s something that’s engrained in my own memory as a kid, and I’m really lucky to be able to work here and try to add facts to the myth.”

And make no mistake, Rodriguez does acknowledge that much of The Alamo is Hollywood-manufactured myth. “There are a lot of inaccuracies in the movie,” he says. “Like, the battle in the movie takes place in the daytime, and it actually happened pre-dawn. There were also characters that John Wayne created for the movie who were not here in real life.” Like the Disney series, Wayne also awards Crockett a heroic death: fatally bayonetted by Santa Anna’s troops, he manages to throw himself on top of barrels of gunpowder and ignites an explosion that decimates a number of Mexican soldiers.

Related: John Wayne museum ready to reopen in Winterset

In reality, though, no one knows exactly how the so-called “king of the wild frontier” met his demise. “There are several accounts of how he died,” explains Rodriguez. “There’s an account saying he was overrun; there’s an account saying that he was captured along with six other men and executed; there’s also [Alamo survivor] Susanna Dickinson’s account in which she remembers seeing his body out in front of the church, and she knew it because of of his hat.” Wayne’s version is the one account that Rodriguez is comfortable calling entirely fictitious. “Crockett didn't blow himself up, because had he done that, we would have lost the church. The gentleman that was supposed to blow up the powder magazines was Robert Evans, and he never made it to that point. So Crockett would not have been the one to blow things up, but it makes for a great Hollywood death.”

A more serious historical omission is that Wayne’s film repeats the Martyrs of the Alamo misrepresentation of the troops inside the Alamo as being predominantly white Americans. “There were Mexican-born defenders fighting inside the Alamo,” Rodriguez says. “We know that for a fact. It was a group of men not only from the United States, but also Europeans, as well as slaves and women and children. It was a full spectrum. But in order to tell the story at the time in 1960, it was easier to hire a bunch of actors that were Anglo. But the Mexican army in the film was largely made up of true Mexican performers, and they worked hard on the movie.”

The erasure of Mexican-born Texans and their specific history from behind the Alamo walls is one of the movie-manufactured myths that most bothers Raúl Ramos, an associate history professor at the University of Houston and author of the book Beyond the Alamo. “In Texas history, the Alamo is talked about as the birthplace of Texas, and it’s this kind of shrine,” he tells Yahoo Entertainment. “There's literally a sign that says you have to take your hat off when you walk in! They also talk about the defenders of the Alamo, and I think the critical word there is ‘defense.’ Defense from what exactly? Because the larger story is that the Alamo was in Mexico at that time, and the majority of the soldiers were Texian. At that point in the war, it was mostly mercenaries who are coming in from from Tennessee. How long did Davy Crockett actually spend in Texas? Just weeks.”

In a 2019 article published by Guernica magazine, Ramos argues that Alamo is overdue for the kind of historical reckoning that’s currently being visited upon Confederate monuments. But that reckoning is complicated by the entrenched perceptions of the site that pop culture has helped shape. “All of the films that have been made took what was a regional story and made it national,” he says, adding that slavery was a key component of the Texas cause that has been airbrushed out of the cinematic re-tellings.

“When folks talk about Americans emigrating to Texas in the Mexican period, they're just labeled Americans, but they were Southern Americans, who were already charting a different course for what the nation should look like,” Ramos says. “The idea was that in order to make Americans care about the Alamo, it had to become an American story. So for someone like John Wayne to play a central figure in a film is to have the viewer identify with him and essentially take a side. It creates a caricature of sorts that’s entertaining, but what I want to remind people as a historian is that both sides were complex and complicated and you can’t ascribe a singular motivation across the board.”

For his part, Rodriguez does consider the Alamo to be a quintessentially American story, one that speaks directly to the idea of of America as a melting pot. “When you look at the full story, it’s a story of cultures blending together,” he says. “And if you tell it correctly and include all sides in the story, you see that it's a continuation of the American Revolution. In 1776, a group of men go against tyranny and create a government that will become a model for many other governments. That idea ends up going to France, which later leads to a leads to the French Revolution … and a revolution in Mexico in 1810, which then leads to Texas Revolution, the Mexican-American War and the United States going from sea to shining sea. You’re just connected the dots of history.”

It’s worth noting that Wayne incorporates Revolutionary War allusions into The Alamo, including a series of guerrilla raids that Crockett leads against Santa Anna’s troops — not all of which occurred during the actual siege. But Ramos is more dubious about Wayne’s attempts to position the Alamo as an American touchstone that the entire country can rally around. “If you think about when Wayne is making the film, there's already a civil rights movement afoot. The Chicano movement hadn’t become national like it did eventually, but it's a moment where a lot of African-American, Mexican and Puerto Rican soldiers that fought for the U.S. have come back to a divided country and there is this litmus test. Films like this were meant to say, “We all agree on this story, but what you’re agreeing to is that your heritage doesn’t matter — you have a new family now.” For a lot of us growing up, that wasn't our idea of what it means to be American. We thought the idea was that you have this heritage and you bring it with you to add to the country, not give it up.”

In 2004, John Lee Hancock directed a new version of The Alamo that tried to offer a more balanced depiction of the battle, and both Ramos and Rodriguez cite as an improvement over Wayne’s film, at least in terms of historical fidelity. (The movie failed to win over audiences, though: made for well over $100 million, it only grossed $25 million in the U.S., putting it on the list of priciest Hollywood failures.) But Ramos thinks that the ideal Alamo movie would be something closer in spirit to John Sayles’s 1996 drama Lone Star — a film that doesn’t focus on the battle at all, but instead wrestles with its legacy in present-day Texas. “One of the last lines of that movie is ‘forget the Alamo,’” he says. “It explores that idea that in many ways history is what's holding us back when history should be what's liberating us.”

Despite its inaccuracies, Rodriguez still believes that Wayne’s film can be watched and enjoyed six decades later as an introduction to a historical event that has deeper complexities that reveal themselves upon further study. “It’s a great way to bring people into the story of the Alamo,” he says, adding that several mementos from the film — including the coonskin cap that Wayne wore as Crockett and a piece of original artwork — are stored in the Alamo vault. “Our job as curators is to try to tell a balanced view of it because history is not always pretty. We're here to help people learn, and it's very important that we tell the story of the Alamo as it is — the good, the bad and the ugly.”

The Alamo is currently available to rent or purchase on Amazon, iTunes and Vudu.

Read more from Yahoo Entertainment