‘Till’ Star Danielle Deadwyler Reveals The Emotional Trauma Of Her Gut-Wrenching Portrayal: “I Am Completely And Utterly Wrecked”

On and off screen, Danielle Deadwyler implores us to not “look away”. Her eyes convey a quality that filmmaker Chinonye Chukwu recognized when she cast the Atlanta native to portray Mamie Till-Mobley, mother of 14-year-old Emmett Louis Till, who was abducted, then lynched by white supremacists in Mississippi on August 28, 1955. When her son’s tortured, misshaped body was shipped home to Chicago, Till-Mobley insisted on an open casket to ensure mourners witnessed first-hand the life-ending cruelty her sweet boy had suffered. “We can’t look away either,” Deadwyler says. “We have to look.”

Related Story

Fresh Face: ‘Till’ Star Jalyn Hall Says He Saw "A Lot Of Myself" In The Tragic Character Of Emmett Till

Related Story

'Women Talking' Star Claire Foy: "Films Like This Need To Become Part Of Cinema, Not Some Sort Of Outreach"

Related Story

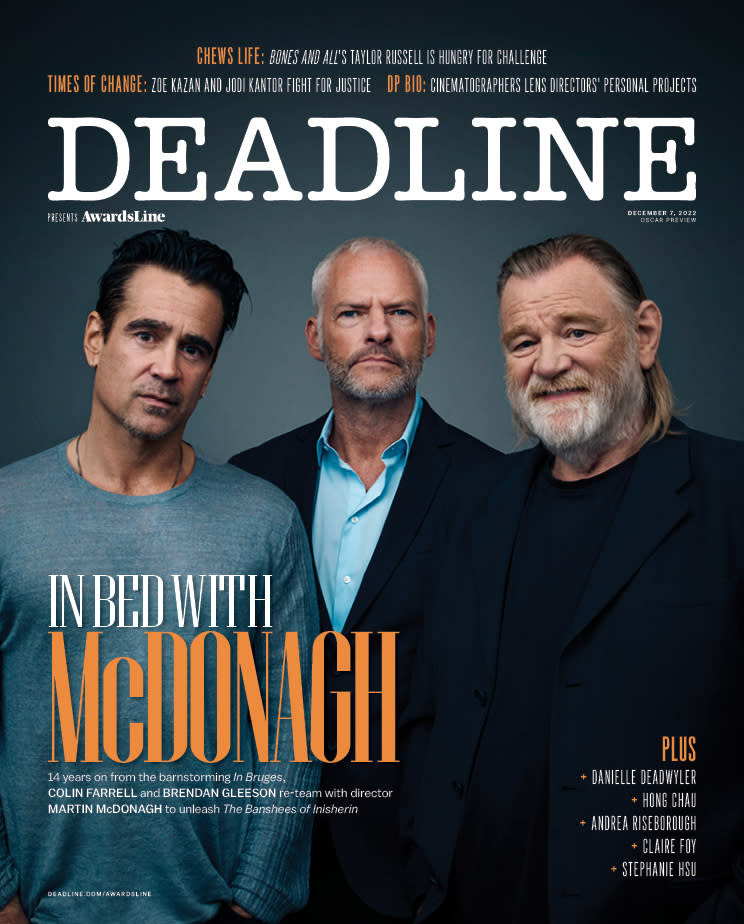

"I Wanted To Work With The Boys Again": Why Martin McDonagh Chose 'In Bruges' Stars Colin Farrell And Brendan Gleeson For 'The Banshees Of Inisherin'

DEADLINE: With all that you’ve been through with this film, what kind of toll has it taken on you?

More from Deadline

DANIELLE DEADWYLER: It’s multi-fold, so there’s before, during, and after. The before was the initial reading of Death of Innocence, Mamie’s memoir, and that was about gauging what the weight would feel like. And then there’s the during. I felt really covered because I know people in every department. I know people from Atlanta who I’ve worked with for years. They’re in wardrobe; there’s my dialect coach; people in every department like background or in location. People who I know are in every department. So, I knew that it’s a community caring for me through it. And then the after, that’s just, well, you’re wrecked. I’m completely and utterly wrecked, and I had to do the ultimate rehabilitative work.

DEADLINE: Which is what?

DEADWYLER: Which is therapy. It’s physical, traditional therapy, one-on-one. Physical therapy, acupuncture, chiropractor. Just not working for the bulk of the year. Journaling, and processing what I went through on a psychic and a spiritual level and stepping away from anything else. Being my son’s mother and having to make those negotiations with him because I’m under the residual effects of that experience. And trying to rear him with that same will that she [Mamie] was trying to rear Emmett. Not muting the fullness of him, and being honest with my son about that, “Yes, I’ve had this experience.” I tell him: “I want to support you to have the greatest amount of freedom that you possibly can, regardless of the things that I have chosen to undergo or that have cosmically come to me.”

It’s a negotiation on all those fronts. I feel like I’m in a good place here, a year out from having done that. But then there is the sharing, which I think this is probably the harder part. I would say that this is the bigger responsibility, trying to assuage people’s fears that this is something that they should be lurching from.

DEADLINE: That moment where Mamie’s with the open casket and the cousin from Mississippi comes and she doesn’t want to look, and Mamie says …

DEADWYLER: “We have to look.”

DEADLINE: Indeed. We have to look. That’s the message, isn’t it really? We have to look, we have to talk about it. We have to think about it. Not to depress the hell out of us, but because as I see it, and see it as a visitor to this country [the United States], not much has changed, what with the rhetoric I’ve been hearing.

DEADWYLER: And there’s great fury in combating the truth of those experiences. Who are we? We can’t complain about it and then turn around and say: “We don’t want to see it either.” They’ve just said they don’t want to see it. Now you’re saying you don’t want to see it? That’s two sides of the same coin. There’s a resistance to actually releasing. There’s a great global grief that needs to be had. And I think that when people come out of the film — or at least the people I’ve interfaced with — they feel a great release, a great climax of pent-up mourning.

DEADLINE: Is that something all people can feel, or is it just Black people?

DEADWYLER: Oh no, this is everybody. Because every parent is having a reaction, a visceral reaction. White mothers, Black mothers, Asian mothers and Latino mothers. I’ve interfaced with them all, and they’ve all come. Everyone fears that. And we’ve just been in this moment of an extended moment. The pandemic is not over but it’s, “over”. We’re all in that. We’ve missed someone’s funeral, or this person was ill because they didn’t get something … There’s a lot of loss. Loss has many faces, many masks. And this is all couched in that same thing. You can for sure mourn what we are witnessing on the screen and the truth of that history. But it’s all deeply connected to what’s happened now. What are the residual effects of racism and white terrorism in this country? And why are certain people getting medical support and other people are not? You can connect it to any theme of human rights in this country. So, yes, it’s there.

DEADLINE: Take me back to the beginning. You were born in Atlanta. Are you an only child or do you have siblings?

DEADWYLER: I have three siblings. My sister is the eldest, I have an older brother, then I’m number three and I have a younger brother.

DEADLINE: You didn’t come out of your mother’s womb saying, “I want to be an actor,” necessarily, but at some point, when you were young, you knew it was something you wanted to explore?

DEADWYLER: Yes, I did. Well, my mother corrected me. I’ve been telling people when I was 3 or 4, she saw me dancing in front of the TV to Soul Train. She said, “Wow, Danielle, it was 2. I should know.” I’m like “OK, you’re right. Forgive me.” And that, I think, was the beginning.

She just put me in everything. Dance was the first medium, which was a natural segue to theater. Those two things are often combined. Movement and dance are just like, Kent Gash [artistic director of The Acting Company] told me this, intermediate language. It doesn’t need translation. And I understand that. It’s always about the physical for me, it begins there. And that just led me into all of the other mediums that I’ve been a part of.

My sister, she’s a screenwriter and playwright. So, I’ve kind of been led down the artistic pipeline through her, but forging my own in other ways; writing and poetry or focusing on being an actor as opposed to her. And my mom’s just supported all of it. It’s just always been there. And even though I didn’t major in theater or performance studies in any capacity, it’s always been sort of my life. So, the academic, which was driven by history, American studies, creative writing, investigations, I knew that art had to be a part of that. The art and the academics have to run parallel.

DEADLINE: Was that something that your parents insisted on, or did the push come from you?

DEADWYLER: I think it was me, and definitely in conversation with my sister. My parents didn’t know what that was. My parents had been traditional workers. My mom worked in legal administration and my dad was in a railroad as a supervisor and in an executive position for over 25-30 years. So, my dad’s retired and my mom, she should retire.

DEADLINE: You said earlier that you physically build the character you’re going to play, so to portray Mamie what were the physical aspects you had to build?

DEADWYLER: I had to be much more disciplined and rigorous. Thinking about 1950s beauty, there’s an elegance. There’s an erectness. There’s great pride. There’s no room to be slovenly. That’s not Black life. At least not with someone of her influence and her family’s influence. We’re deep church-going people and proud, prideful people. Black life in Chicago or Mississippi for that matter, you’re dressing up for the public, you’re presenting well. And so that physicality calls for something. The string is pulled tight, all the way up to heaven, as they call it. You stretch your body up to the skies. [Costume designer] Marci Rodgers’ wardrobe calls for you to do that.

DEADLINE: There’s that scene where you and Emmett are in the store buying a wallet and the salesperson approaches you. I would not have approached you to say [sniffily] there’s another department you can go to because there’s something in Mamie’s demeanor that says … how dare you. In the way she holds herself.

DEADWYLER: We hold ourselves, yeah.

DEADLINE: I was raised … listen, I wear a suit to go and buy milk.

DEADWYLER: It’s what we’re reared in. The experience is different, as opposed to coming in with me with a skull cap on or me in the dress and perceived differently in a way that one is perceived if I have natural hair or opposed to straight hair, it calls for something different which is deep in the psyche of Western culture and largely on Black people. Those things are transposed on our experience. And so, there is something that happens when we make a particular kind of choice.

DEADLINE: Mamie’s an executive and a Black woman so that immediately gives her, for want of a better word, a certain pedigree.

DEADWYLER: Yeah, a certain cache.

DEADLINE: And we see that immediately. What else was involved in the construction of her?

DEADWYLER: Well, I think for me it was setting the tone of the environment. That’s getting into the headspace of cultural, social dynamic, understanding the influence of the family. Her mother moved from Mississippi to Chicago and therein became a kind of reception for people who were moving there after. So, she’s this kind of person interfacing with everyone who’s there already and those who come. And sharing resources to a community. So, it’s a person of influence, a family of influence. And then painting the picture of what that looks like in 1950s Chicago. What their community was, how far their reach is; their influencing the church and then what that does in connection to Mississippi.

So, I was doing a political, and social and cultural historical diving. But everything wasn’t totally necessary. I did a lot for my own sake. All of the violence that was taking place before she [Mamie] got there. What kind of firestorm he [Emmett] walked into that precipitated that kind of horror. Painting that full picture and thinking about womanhood in comparison to Carolyn Bryant [the white woman who claimed Emmett had assaulted her]. Those were the kind of things we were getting into. How she’d be negotiating the space, be it public or private.

DEADLINE: What were the discussions that you and Chinonye Chukwu had before the cameras rolled? Was there anything key that stuck with you?

DEADWYLER: Making her human. We always see a figure who’s pedestal-ized, who is this great mother of service for the civil rights movement. But they’re human beings making choices, who are flawed, and who have a growth period. That whole experience, the rest of her life, is this massive, beautiful growth into mothering the world. And so, it was really important for us to talk about the rage that rightly wasn’t able to be witnessed.

She’s negotiating. What does it mean to go through this with family? Who is she fighting for at different points of this terrible, yet joyful, effort at legacy and justice? Those are our intentions. She’s a woman who did things. She smoked, she drank beer here and there. And she loved her son, and she had a beautiful fiancé who became her husband. She had her mother, her father. She had a full life. And we don’t we always talk about what that means. What it means to be a human after you’ve lost the loved one. We don’t always worry about, we don’t exactly think about, consider the name of those who carry on that legacy. And that’s what we wanted to get to.

DEADLINE: When Emmett’s casket comes back from Mississippi and it’s in the funeral parlor you touch his tortured body. I know it’s a life-like dummy of some sort, I know that. Even so, did you have to prepare yourself in some way?

DEADWYLER: The whole shoot was that, because there’s tension. The tension oscillates, but it’s just present the entire time. I don’t really remember preparing specifically for those things. I can’t locate a single thing that was done. I know that the funeral home scene where she witnesses the body for the first time, that’s one of the scenes that we did a director’s session for. So, I had interfaced with it a little bit. I knew an inkling of what was about to be endured — and I truly say an inkling of it. But the whole thing is tension. The tightrope is pulled, and I think she falls off because you can’t possibly balance on that. You fall off, you get back on it. You struggle, laugh it off, and you get back on it. But the beauty is that she stood up and that she transmuted it into something greater.

DEADLINE: I was reading something that Whoopi Goldberg said, something about not being sure whether you could have any fun. Whether you could laugh on set.

DEADWYLER: Oh, yeah, I think I heard that. I was the goofiest goof. There were plenty of laughs. I did renditions of gospel songs with Frankie Faison and I would do dancing. I would imitate stuff like from churches and the way folks dance in the middle. It’s just stuff that Mamie doesn’t do. It wasn’t about staying in character the whole time. The levity was necessary. We joked a lot. We talked a lot. We joked on Tosin [Cole, who portrays Medgar Evers]. We don’t survive unless there’s humor.

DEADLINE: How was your relationship with Jalyn Hall, who plays Emmett?

DEADWYLER: Yeah, he’s a beautiful kid. He was 14 when we were making it. He’s 16 now. And his mother’s there and she’ll tell you that his mother’s his best friend. And so I just marveled at that because they’re a unit. She’s ushering him through this. She’s as part of the process as he is. And me connecting with her and talking with her. Yeah, joy was had, joy was had.

DEADLINE: I know your career. I know it didn’t come to you at 19. You worked to get here. This magnificent performance has propelled you here on the back of hard work.

DEADWYLER: Yeah, it didn’t come to me for a reason. And I’m OK with that. When I was young, I wanted to rush too, but it didn’t happen that way. And I’m pleased that it didn’t, because the slower road has just been that much more instructional.

Best of Deadline

Sign up for Deadline's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.

Solve the daily Crossword