"I’ve been booted out of King Crimson about three times": Bill Bruford on a life in music

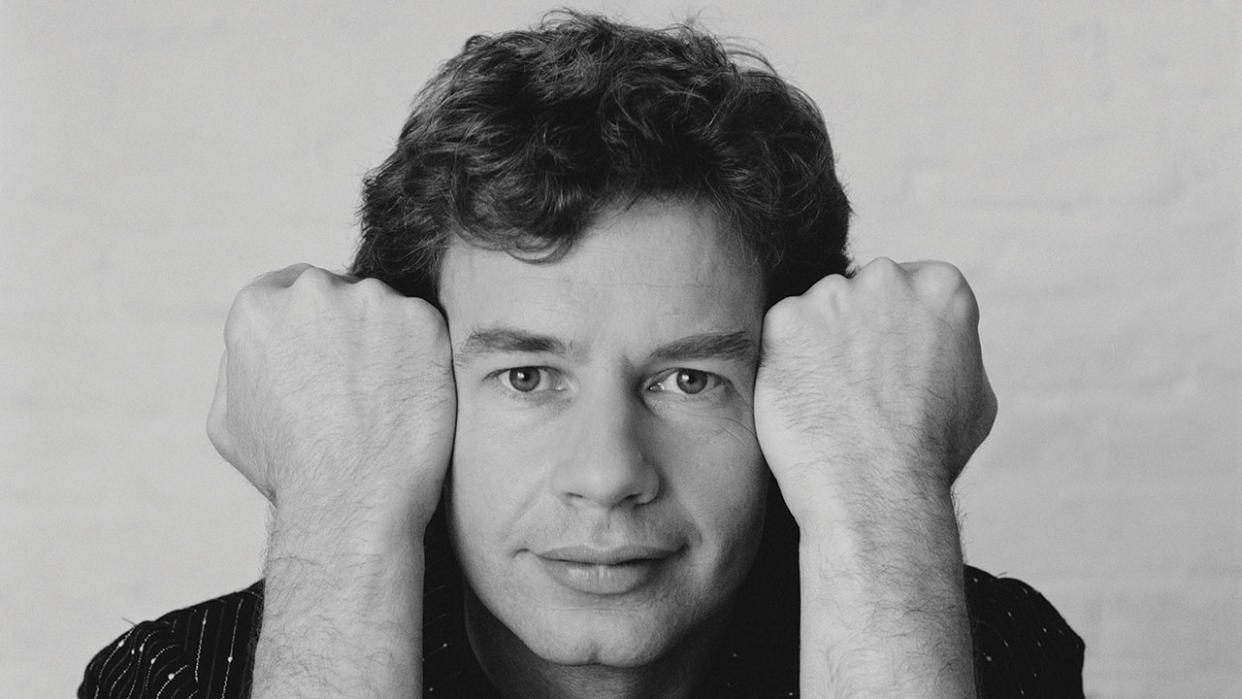

When Bill Bruford settles down in front of his computer to talk to Prog, he is, of course, precisely on time. He’s sat in his home office in Surrey and his Zoom backdrop displays an undulating range of rugged fells speckled with grass and scree, nestling under a blue sky. Attired in a smartly pressed country check shirt and a practical-looking gilet, he looks very much like a doctor about to undertake a consultation with a nervous patient. It’s worryingly easy to imagine this genial 72-year-old, who was inducted into the Rock & Rock Hall Of Fame in 2017, leaning forward and starting the conversation with a polite but firm, “Now, what seems to be the trouble?”

In fact, this morning’s chat is prompted by the release of the six-CD Making A Song And Dance, a new box set covering the drummer’s entire career. It’s a very personal selection that includes Yes, King Crimson, UK, ABWH, tracks from his solo and Earthworks albums, and numerous guest appearances with artists as diverse as Roy Harper, Piano Circus, and the Buddy Rich Band. “This isn’t something I’ve done overnight,” explains Bruford. “Obviously, there’s a certain amount of editorial stuff going on. It took something like six or seven months to select the 70 tracks spread across these six discs.”

With his customary fastidiousness, Bruford has organised the music into four distinct categories. “There’s collaborations that involve working with Yes and Crimson, for example. The Bruford band and Earthworks come under the heading of The Composing Leader. My work in duos, firstly with Patrick Moraz in the 80s and with Michiel Borstlap in the 00s, showcases improvisation and there’s also a disc that has my contributions as a special guest,” he says, justifiably proud of the finished set.

But hang on a minute. Didn’t Bill Bruford retire in 2009? He guffaws loudly. “No, no, no. You’re like my wife, you’ve got the wrong end of the stick, you didn’t understand. Ha!”

Calming down, he continues, “My biggest error was the omission of the simple words: ‘from public performance.’ I retired from public performance. But everything else goes on, you know, the struggle as an artist and all that. It all sort of goes on, you know? I retired from public performance. I don’t play the drums anymore. Put it like that. But I agree looks can be deceptive because this is the third box that I’ve done in six years. Who would’ve thought that? I mean, I didn’t think six years ago I’d be talking to Prog in 2022 about a box set. I’m as astonished as you are.”

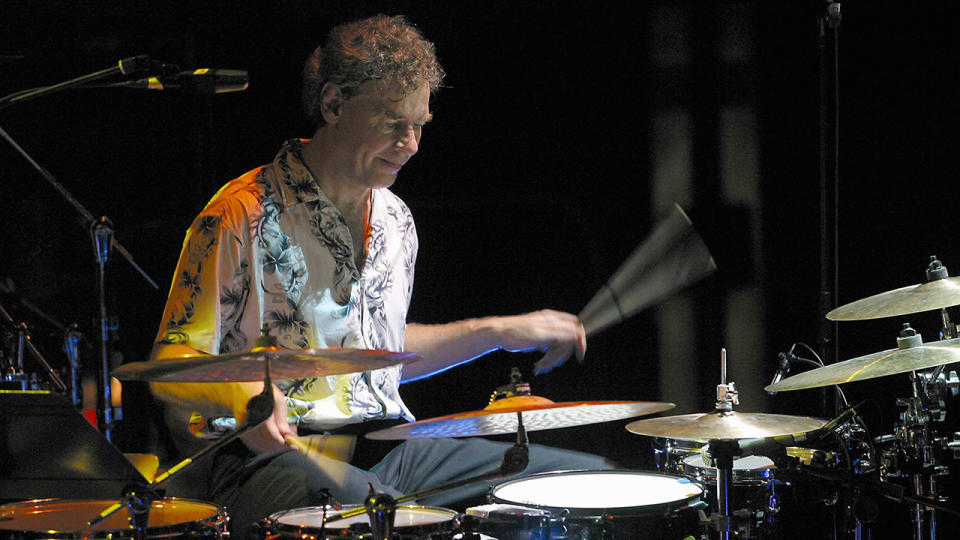

Astonishment is a frequent reaction when both punters and players alike encounter Bruford’s work. The man with the heat-seeking snare developed his signature sound so early in his career that the high-ringing percussion was not only instantly recognisable but served as a benchmark of quality. Whether with top-flight acts such as Yes, King Crimson, UK and ABWH; his own project Bruford; the electric and acoustic versions of his Earthworks groups; or the explorative duos he formed with pianists Patrick Moraz and Michiel Borstlap, his presence has added grace, subtlety and, when the occasion demands it, the injection of a startling rush of thoughtful, incisive power whose precise application immediately transforms the music it serves and, in the process, takes the breath clean away. Even removed from the bright lights of a storied career that began in 1968, Bruford’s role as a guest player and, in some cases, agent provocateur, has notched up an impressive list of associations that include Genesis, National Health, Roy Harper, and even a short excursion with Gong. Taking all these connections together pretty much guarantees that any account of progressive music in the 20th century has to include Bruford’s name in the index or it simply isn’t worthy.

The prospect of change can be daunting, unsettling and sometimes downright upsetting for many of us, but not in Bruford’s case. Change is something he’s always thrived on. From a commercial point of view, leaving Yes in 1972 to join King Crimson, a group then fraught with problematic line-ups and a limited lifespan, seemed like a mad idea to many observers at the time. Yes albums were then hitting the high end of the charts whereas King Crimson records were barely scraping into the lower reaches of the Top 20 – why on earth would anyone give up on that kind of success and take a pay cut? For Bruford, it was always about putting himself in situations where he could learn and improve. Once you’ve arrived at the point where you’re just repeating yourself or sitting in one place because it’s comfortable or expected, then that’s the moment you move on. And King Crimson unexpectedly came to a halt in 1974, 1984, and, for a final time in Bruford’s case, 1996.

The drummer doesn’t do much in the way of nostalgia. For him it’s a case of sticks down, job done, move on. Yet, wasn’t he even curious about what some of his old bands did next? For example, after leaving UK did he listen to 1979’s Danger Money with Terry Bozzio? “I did not. Nor have I heard Tales From Topographic Oceans. I’d rather move on quickly to the new thing rather than indulge a curiosity of the old.” His preference is to step away, he says. “You’re trying to put on a new suit of clothes, you’re trying to dress differently. I don’t want to keep wearing the clothes of the last band, as it were, or keep going back on how it could have been or could I have done this or that? Or why I was kicked out or did I want to go? All that stuff I find very marginal. Once the decision’s made I’ll move on.”

Prog wonders where that stamina and drive to keep pushing forward comes from? “It comes from a desire to make a contribution and if I’m going to call myself a drummer, I want be a real drummer that changes things as all my heroes did: Art Blakey, Max Roach and Joe Morello. I just wanted to follow down that particular path and make a contribution. The trouble with that is I like to upset things, though not all the time, but there will be an element of upsetting things. You can’t make an omelette without breaking eggs and it’s within the musician’s lifestyle, I think, that you’re going to have to suffer somewhere. I think there is an element of suffering involved. If you want make something that’s going to last then something, somewhere will have to change and where there’s change there’s usually upset.”

That upset can be manifested in a very direct, visceral manner. He recounts the tale of when a radically restructured King Crimson returned to active duty in 1981 with Adrian Belew and Tony Levin now in the ranks. It was still early days for the quartet, who were playing in Germany, a country that had been very enthusiastic about the band’s previous incarnation. Despite what Bruford judged to be a good performance presenting some interesting new music, they went down badly with the crowd. As the band were leaving the stage a big package of meat was thrown from the audience and landed with a damp thud at his feet.

“You see what I mean by change? Clearly the guy who threw his chopped liver at me in the German audience was upset by something, you know? During Robert Fripp’s comings and goings with King Crimson, I felt, on the whole, that I got used to it. Every few years there wouldn’t be a band [laughs] and somehow I got used to it and I was toughened by that. I think I developed a fairly thick skin and I don’t take it personally in any way, shape or form. I’m not that kind of a person.”

The conversation turns to Toby Amies’ documentary In The Court Of The Crimson King, which had its première at the SXSW Film Festival in Texas in March 2022. Bruford is one of several ex-and current members interviewed for the 90-minute film and has seen the finished edit, although the documentary won’t be on general release until later in the year. “It’s terrific,” is his verdict, but adds, “I was thinking about myself having a thick skin and I was just thinking I’m not Adrian Belew in that sense because Adrian looked so unhappy and so emotionally wrecked by this process with Robert. Whereas I always felt rather strengthened by being in his orbit. I found it all rather encouraging even though he might be saying, ‘Don’t play that, Bill’ all the time. I felt rather strengthened and quite different to some of the, shall we say, softer characters perhaps like Mel Collins or Ian McDonald, all terribly sad stuff. I’m not that person and I don’t know why. I’ve been cheerfully booted out of King Crimson about three times but I keep turning up like a bad penny!”

The phrase ‘what goes around, comes around’ might have been invented for Yes and its oft-quoted ‘revolving door’ policy regarding its personnel. Bruford’s return to the fold, albeit initially by proxy, happened 16 years after jumping ship in 1972 and came in the shape of Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe. It’s a project for which he retains some affection; a radio edit of Brother Of Mine, from their 1989 self-titled album, is included in the box set while 1991’s full-band creation, Union, is conspicuous by its absence.

“As a band, Anderson Bruford Wakeman Howe wasn’t a bad first album. I think it did quarter of a million, which wasn’t too shabby [it shifted half a million units in the USA alone]. When there’s money involved, then people in suits appear and want to hear takes of the record as it’s being made and make suggestions. Like, ‘We should have more tambourine or louder tambourine on the chorus?’ So, the problem when there is money around, and there was money around, is that he who pays the piper calls the tune. So, before I knew it, it suddenly turned into Yes with a whole bunch of California guys welded on because someone in upper management decided it would be a better record and would sell more copies. I’m not even sure that the second record sales exceeded ABWH, especially since on Union you paid eight or 10 musicians including session musicians. So it turned into a dog’s dinner.”

The problem facing Yes was being increasingly driven by the business side, relying on expediency rather than artistic decisions. “The band has always consumed money fast and therefore needs more money coming in and therefore has to maintain a profile. So at that point, you’re becoming more and more beholden to money people in suits and you’ve got to play and provide what’s wanted. Now, you don’t have that problem with Bruford or Earthworks or any of that stuff. What you get is what I want to give you and I love that.”

Leading his own projects, the Bruford band with Allan Holdsworth, Dave Stewart and Jeff Berlin, and later Earthworks from 1986-1988 and the second incarnation of Earthworks that ran from 1997-2008, were very much a labour of love for him. Both provided him with a platform as a composer able to follow his jazzier inclinations. Albums such as his solo debut, Feels Good To Me (1978), and the Bruford band’s One Of A Kind (1979) and 1980’s Gradually Going Tornado are packed with knotty writing and lithe finesse that wears its instrumental virtuosity very lightly indeed. Earthworks showcased some of the very brightest young talent in the UK jazz scene. Pianist Django Bates and sax player Iain Ballamy from Loose Tubes added a tremendous fire to Bruford’s writing, catching them at an early moment in their career.

“Django Bates and Ian Ballamy were babies. I remember going to Iain Ballamy’s 21st and he’d been in the band a couple of years. But I like it when the older guy, who may not be the most technically accomplished musician in the band, uses the services of great younger guys, who probably are better equipped than he is. It’s a balance of needs and requirements. I need their hot blood and their skill. They need an international platform and I can offer that. So you have a mutual exchange and the best groups work that way because then everybody’s there because they can get something out of it.”

Looking back at his career there are points along the way where he has been able to move between very different worlds. Here’s Bill Bruford on Atlantic Records playing Madison Square Garden. There’s Bill Bruford imbibing the atmosphere of New York’s jazz clubs Birdland or the Iridium. At times the recipient of the big bucks, recording an album in upstate New York or Montserrat. Then again, the same man is busy at his office desk sorting out reservations at a Travelodge just off the motorway so he and Earthworks can pile into their rental van and get on the road to the next show. Above all, whatever the extreme, he’s comfortable in his own skin.

That kind of confidence, that innate sense of purpose and direction is hardwired into Bruford’s psychological makeup. In his capacity as a professional musician, he’s never agonised over what the next step is. He doesn’t do personal doubt: “I sort of always know where I should be. It might be painful being where I should be, but I’ve usually gone where I should be. I’ve been happy with my choices, and there have been a lot of choices, a lot of decisions that you make. Should I play with this guy? Should I play with that guy, you know? Is it this song or that song? You make these decisions hopefully in the best interests of those around you and particularly yourself. I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again: I’m one of those few people I know who has played what I wanted, when I wanted, where I wanted, and with whom I wanted, throughout my entire career.”

It was always unlikely that one would find Bruford putting his feet up after his departure from live performance. In 2009 he published Bill Bruford: The Autobiography. Yes, King Crimson, Earthworks, And More to great acclaim and, in 2016, graduated from the University of Surrey with a PhD after examining aspects of creativity and performance psychology, a subject he examines in some considerable depth in his 2018 book, Uncharted: Creativity And The Expert Drummer. When he’s not putting box sets together, you’ll find him writing academic articles. As with his drumming on stage and on record, from a distance Bruford makes the process look seamless, with no lumps or bumps. However, the trick he mastered long ago is making all that time, all that effort, all that commitment to constantly improving and challenging himself, appear effortless. After all that, one might think that for someone like him, with his experience in the field, getting his doctorate was easy.

“Are you kidding me? No, it was real sweat,” he says indignantly. “Work would come back that was just simply unacceptable and there were the two most terrifying things you’d see in the margin, both beginning with the letters ‘S’ and ‘W’ and there would be a red circle, and another ‘S’ and ‘W’ red circle down the page. That first one stands for ‘says who?’ Because you’ve said something and it’s completely unattributed your supervisor says, ‘You think I want to know what you think, Bill, forget it. I don’t care what you think. I want to hear the strength of your argument here. Everybody’s got an opinion. That’s called journalism.’ The other ‘SW’ is ‘so what?’ You’ve said something, where is this taking us? It adds up to nothing, it means nothing. So what? Says who? So these are great things that all academic writers have to bear in mind all the time because you’re wasting people’s time if you don’t.”

One imagines that receiving his PhD and formally becoming Dr Bruford, the unaffiliated early career scholar, must have given him a sense of real achievement? He pauses a moment considering this. “Yes, it’s a great feeling but so is finishing an album. I must admit, I like having a physical outcome and a CD or a track or finishing a track in the recording studio or a book, and I’ve done a fair bit of academic writing in the last five years, too. These visual items are artefacts of my cultural existence and they speak volumes about the kind of person I am and, of course, they tell me what kind of a person I am. There’s never been a dull moment.”

And with that our time is up and Dr Bruford moves on to his next appointment of the day.

Originally printed in Prog Magazine #130.