Vince Clarke: "Martin Gore brought along his synthesizer, we looked at the thing and thought, this is a lot easier than learning chords on a guitar and you only need one finger to play it"

Vince Clarke is almost unique in the synth-pop world for attaining significant success with a multitude of electronic bands throughout the ’80s and beyond. Having studied violin and piano at school, the South Woodford, London-born songwriter teamed up with schoolmate Andy Fletcher prior to the formation of Depeche Mode, then promptly left the band after their debut album Speak & Spell (1981) hit the top 10.

Shortly after, the introverted electro-pop mastermind met Alison Moyet to have huge but brief success with Yazoo before scoring even greater chart triumphs as one half of the interminable dance-pop duo Erasure, with vocalist Andy Bell. The restless Clarke has also collaborated with Martin Gore for the 2011 album VCMG and other electronic luminaries such as Heaven 17’s Martyn Ware, Jean-Michel Jarre and Orbital’s Paul Hartnoll, amongst others.

Indeed, it was during Clarke’s collaboration with Gore that he was introduced to the world of Eurorack. After building a system and spending a few years simply admiring it, he began to dig a lot deeper during the pandemic, surfacing a few years later with a series of tracks simply titled Drone. Persuaded by Mute Records boss Daniel Miller to elongate those recordings, Clarke finally releases his first solo album Songs of Silence – a dark, minimalist ode to sci-fi film soundtracks.

Was your early fascination with electronic sounds led by the music that was around in the ’70s and early ’80s or the technology itself?

“It was the new records that I started hearing in the early ’80s. When bands like The Human League, Soft Cell and OMD started releasing records, it became kind of a scene in my home town for myself and likeminded fans. We were interested in this stuff whenever it was played in the front rooms at various friends’ parties, but it wasn’t a genre back then – it was a whole new sound.”

When you started making electronic music, what access did you have to gear, which was presumably quite expensive at the time?

“At first, I was making music with Andrew Fletcher – we had a drum machine, he was playing bass and I was playing guitar and singing badly. Then Martin Gore, who was a friend of Andy’s joined and he had his own synthesiser. We looked at this thing and thought, okay, this is a lot easier than learning chords on a guitar and you only need one finger to play it.

“That’s when I started getting interested in the technology and the fact that I could maybe reproduce or do something similar to the music I loved at the time. It was all-analogue and very expensive, but then so were guitars and amplifiers, so we had all our synths on HP [hire purchase].”

You must have been encouraged by the fact that electronic bands were starting to become massively successful around that time?

“It’s funny, but I really liked the early Gary Numan records, yet never really saw that as something I could do myself. He sounded really polished to me and I could never work out how he did it, but then I wouldn’t really consider that as early electronic music because he was in a traditional rock band using synthesisers. It wasn’t until bands like OMD came along, and The Human League who were only using synthesisers, that I thought I could do something like that.”

You obviously wanted to be successful, but it was also fairly evident that you didn’t want to front a band. Did you realise very early on that you had to find another voice for your music?

“Do you mean did I realise that I couldn’t sing [laughs]? I had no illusions about my singing style or capabilities at all and I’ve been very fortunate to have worked with some amazing vocalists, which really proved the point. These people were just mates or within a circle of mates, so to speak. Alison Moyet was in a punk band called The Vandals where my best friend was the guitarist and we knew Dave Gahan because he was someone that we used to see in clubs who was really fashionable, as opposed to us.

“Erasure was different because I was working in the studio a lot trying to write songs and make records and after a discussion with the producer we decided that working with different people would be interesting but we really needed someone to be there all of the time. I advertised for a singer in Melody Maker and Andy Bell came along for the audition. He was from Peterborough, but we had very similar backgrounds, which cemented our relationship.”

Most people were throwing away their analogue gear in the late-’80s and embracing MIDI and digital synths. Was it the same for you?

“I was always interested in the new technology as it came out and fortunately by that point I could actually buy the stuff and try it out. So I did go through a phase of buying the latest and greatest synthesisers, but that got a bit tiring after a while because you had these really famous early digital synths with amazing presets but everyone was using the same ones so records started sounding the same, at least to my ears.

“That’s when I started rediscovering analogue equipment where, because there’s no memory, you have to find the sound and make the sound. I’ve always found that much more satisfying than hitting a button or using a preset.”

Nik Kershaw said recently that he literally threw his Oberheim OB-8 and Roland JP synths into a skip…

“The OB-8 I can understand because it’s a dreadful-sounding synthesiser, but the Rolands… hmmm, I think that might have been a bad decision. I kept the analogue stuff and actually got more interested in it and started searching out even older pieces of equipment. I built a collection of modular synths, learned how to use those and started incorporating them into our music.

“The first one I bought was a Roland System 100M, which was like a mini version of the Roland System 700. It came with pages that illustrated how to patch a sound and make your modular synthesiser sound like a flute. I did no experimentation with it whatsoever, I was just following the instruction manual, so it took me ages to figure out how to use it.”

We were trying to track your more recent fascination with Eurorack and wondered whether it might have begun around the time you collaborated with Martin Gore for the instrumental electronic album VCMG?

“When Martin and I started working together everything was done remotely, but I did ask for his advice on getting into modular and he was kind enough to make some cool recommendations that would be a good starting point. He recommended some basic filters and stable oscillators, but there weren’t the zillions of modules that exist now.

“At the time, I created a small Eurorack system and messed around with it a little but didn’t really use it. It’s not that I lost interest; I just got more involved in making Erasure records. It wasn’t until I started working on this current album that I went back to the Eurorack system and delved much more deeply to discover what it did.”

How would you compare Eurorack to some of the modular-related gear that you embraced earlier in your career?

“The most interesting thing about Eurorack is the fact that you have these manufacturers from all over the world thinking about sound in different ways. Back in the day, your ideal modular system might include a filter from Prophet, an Oscillator from Moog and an envelope from someone else, but you couldn’t put it all in one box like you can with Eurorack.

“It’s incredible considering these manufacturers are very often making modules in their garages and all have very different approaches, but Eurorack is not actually a synthesiser, it’s a universal connection system, so the modules work off the same power supply and can be connected in the same way.”

You once mentioned that CV/gate is tighter than MIDI, which might surprise people…

“I used to use a fantastic 16-track MIDI sequencer called UMI, which worked off of a BBC B Microcomputer. This was very early MIDI days, but we used to use it live and for all our own recordings. I don’t know what happened, but at some point I started noticing these timing discrepancies between the tracks. Unlike most people, I like music to be really robotic-like and extremely tight – I’m not too much into ‘feel’.

“We recorded an Erasure album called Chorus and it was all programmed with the UMI sequencer and the files were then transferred to an analogue CV/gate sequencer to record the tracks and trigger the sounds. We used to use a CV scope to measure and bring things into time, but when we looked at what was coming out of the MIDI sequencer, the timing was drifting and shifting all the time, especially when we were recording more than one track.

“We just found that the CV/gate sequencers were much better and tighter and would use the CV scope to take the kick and the snare and nudge them slightly to the left or right to make them exactly in time.”

You mention that you prefer your music to have a very robotic feel. Some of us don’t really like hearing electronic music played live because it never sounds as precise as the original recordings. Is that how you feel?

“I’m like you, when I go to hear a band live I don’t want them to sound that much different to the record I bought and I’m totally not into jamming. Every now and then I’ll go down the pub and watch a jazz band while I’m drinking a pint of Guinness, and that’s really entertaining. Obviously these people are incredibly skilful and talented, but part of it is that I can’t do what they do, so I don’t like it [laughs].”

For your debut solo album, Songs of Silence, was the sole reason for making it modular-only due to you having to relocate studios?

“No, because the album was recorded in my old studio at the beginning of the Covid lockdown. At that time, I was just interested in making tracks, recording stuff and learning how to use the Eurorack system. It was never my intention to make a record – I was just watching a lot of YouTube videos about oscillators, which was ‘fascinating’. When I make an album, the most enjoyable part is the process, not the release or anything surrounding that – I just like being in the studio fiddling with knobs.”

We’re guessing Mute Records convinced you to release it then?

“Daniel Miller asked me to send him all of these drone-based tracks that I’d made and then got back to me asking if I’d be interested in turning them into a record, which was a complete shock to me. We’re good friends, so I didn’t send the stuff with the idea of us putting out a record and I didn’t actually believe him – it was only when the guy that does the artwork for Mute got in touch that I thought, bloody hell, they’re actually going to release it.”

Were the tracks you initially sent to Daniel at the demo stage?

“They were pretty complete. The only thing that really changed between then and the record being mastered was that I had to make the tracks longer. That was relatively easy to do even if it took quite a lot of work, but I find doing all of that tedious stuff quite satisfying. I like attention to detail, listening to things very, very carefully and figuring out what parts can be edited to fit with other parts. That’s why no one ever visits me in the studio.”

You once wrote that Depeche Mode had become a little too dark for your tastes, but Songs of Silence is a pretty dark album…

“Yes it is and that wasn’t my intention – it was just a reflection of the way I felt at the time. It was about my environment and the shit that was going on in my life, but I was also doing these two-hour shows of electronic music with a friend for local radio. At first we just started playing electronic hits, then after a while we realised that we had to start playing new music, which was when I started discovering all of these amazing artists making experimental ambient music and soundscapes.

“I was always curious to know how people make that type of music interesting. I’ve been writing songs for a long time and rely on verses, choruses and chord changes to create drama, but with an ambient track you’re relying on textures, slight changes as the track evolves or sparse events happening once or twice in a track, and that was a whole new learning process.”

Did it help to create various themes in your head as a pointer or did you simply rely on the modular equipment to spark your imagination?

“Originally, the tracks were all called Drone 1, 2, 3 etc., and it was only when the album came out that I had to start thinking about titles, but watching sci-fi films on Netflix and listening to the soundtracks was really what inspired a lot of the beginnings of tracks.

“The first one that really got me going was Blade Runner 2049, which I thought was never going to be as good as the first one, but the way they joined up the two films was genius. Then I thought, okay, I’m going to go downstairs and write the music to Blade Runner 3 and all of these tracks just evolved.

“I guess it became a bit of an obsession, but I loved the process of being in the studio and listening to sounds that stirred me emotionally. It was very therapeutic, and some people have said that the album’s been therapeutic for them too, which certainly gave me solace.”

You mentioned that you were also listening to various artists who were making ambient and experimental music. Which ones stood out?

“I’ve always been interested in anything to do with sci-fi, or horror, so people like John Carpenter have been quite inspiring, but I started getting into music when synthesisers weren’t really synthesisers, they were just rooms of machines. On the radio show, we played a lot of stuff from the ’40s and ’50s when that technology wasn’t fully developed, so there were no artists that I particularly wanted to sound like, but everything just filters into your head – you can’t help it.”

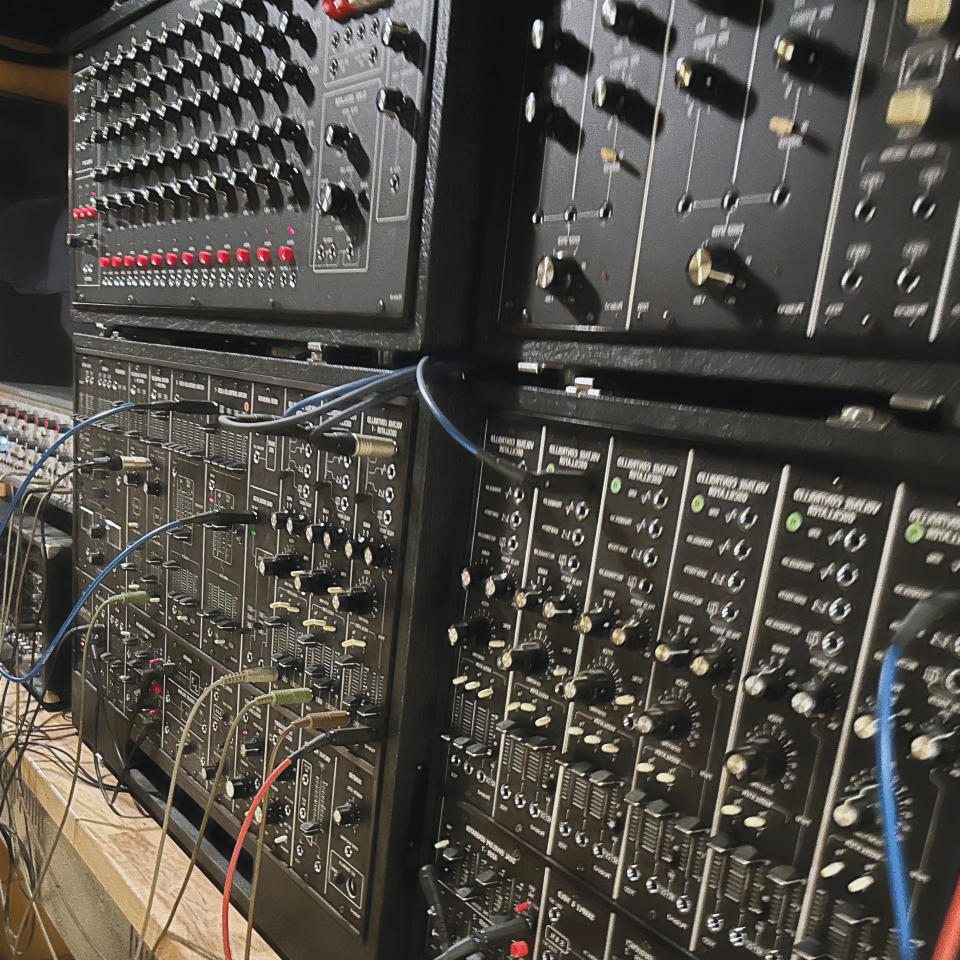

What specific modules were you most reliant on to create the drone tracks?

“I have two small modular systems that sit side by side and I used a lot of sequencers, but I didn’t turn to any one manufacturer in particular. I’ve got some really old-fashioned modules from Roland and Moog and some of the envelope modules are so fast and super-furious that they sound like a Prophet Pro-One. It’s a crazy, crazy world because there are so many modules out there and you can modulate them in so many different ways, whereas you could only go so far with the older analogue gear.

“We could turn this into a really rude interview, but now you can stick a mini-jack where you could never be able to stick a mini-jack and there are far more entry points. I don’t think I’m addicted to modular, but I’m addicted to finding new sounds and new ways to change sounds – that’s what sparks my curiosity. What I mostly wish for is for things to be stable and vaguely in tune. Some modules aren’t designed to be stable, which is also interesting, but there are ways to get around that.”

You used Logic Pro to sequence the modules and arrange the tracks?

“For this particular album, I’d record a sound that I thought was close to how I wanted it to be and then found Logic was able to do a lot of the sound manipulation and sculpting using its built-in plugins and some external ones, of which I have too many to mention. I don’t tend to use modular effects – I have reverbs and echo units and do all of that stuff in-the-box after I’ve recorded the raw sounds.”

Some tracks go further than just using modular synthesis. For example, where did you obtain the choral vocal for the operatic-sounding track, Passage?

“I had most of the track finished, was listening to it quite intensely and thought it was very machine-like but needed to be paired up with something organic-sounding. The idea of adding an operatic tone popped into my head and I used the web service Fiverr to get in touch with a very nice lady in the UK who performed a very simple phrase that I’d written out that was very loosely based on one of Puccini’s arias. There was no way that I could make a synth sound like she did – it was something else.”

The Lamentations of Jeremiah has some lovely cello parts. Were they recorded in a similar fashion, but with a cellist?

“That track started off as a very sci-fi soundscape and then I sent it to my friend Reed Hays and asked if he’d do something on top. He came back with this cello thing and I was completely blown away because it took the track from sounding very machine-like to something much more humanistic, if that’s a word. As with Passage, both contributions worked perfectly well and it was the same with the track Blackleg.”

Blackleg is remarkably atmospheric. Where did you derive the vocal prose?

“Many years ago, I was working with Martyn Ware from Heaven 17 making music for art installations, and he just handed me this sample of an old folk song from the late 19th century and wondered if I could make something of it. I always loved the sample and could never make it work on a track, but I thought it might work for this one. I literally stuck it in the track and it just sat there beautifully without having to even time or tune it.”

Do you have any intention to play the album live, which would no doubt be complicated considering you used a Eurorack system to make it?

“We’re actually doing a show in London very soon at the London School of Economics. I’ve been preparing it for a couple of months now, but it’s going to be a visual event so I’ve been programming the visuals and working that out.

“The idea is for it to be visuals with music rather than the other way around and it’s meant to be very immersive. I’ll be on-stage with Reed who will also be playing keyboards alongside a really nice lady doing vocals for the operatic piece. We’re going to use a couple of fantastic Roland SP400 samplers to trigger stuff and a Revox 2-track tape machine, so we’re going to be fairly busy.

“To be honest, I’m very nervous about it because there’s a lot of technical stuff going on, which always makes me anxious, but as long as we don’t fall off the stage and nothing explodes we’re going to hopefully take the event to New York and other places. It won’t be a tour, but I like the idea of doing these types of events as long as people are interested.”

Presumably, you’re still working with Andy Bell and Erasure. Does that process necessitate using a very different suite of tools?

“I’ve been preparing some demos so hopefully Andy and I can get together at the beginning of next year and start writing a ‘proper’ album. I won’t tell you the method – the way I work on tracks for Erasure is done in a completely different way, but the idea is to always keep things interesting by trying new techniques. Once you stop learning, it’s over.”

Learning in terms of the technology you use or do you find there’s still things to learn about writing an electronic pop song?

“You never stop learning with technology, but that also applies to writing songs. As you get older, you hopefully get better at it. When Andy and I work together, we’re really quite good at knowing when stuff isn’t working or doesn’t sound right. Neither of us fights our own corner, so we’re good at letting things go before moving on to another song. It’s always been that way and it’s a very important aspect of our partnership.”