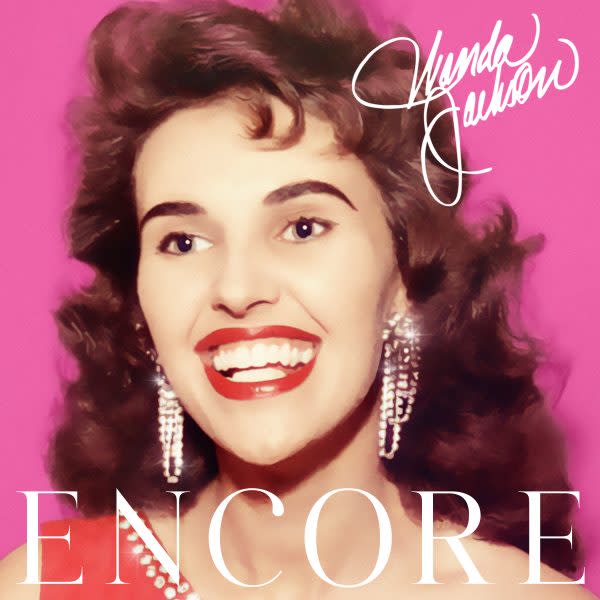

Wanda Jackson and Producer Joan Jett on the Rockabilly Queen’s ‘Encore’ — and Whether It’s Really the End of the Road

Before discussing country-rockabilly legend Wanda Jackson’s so-called final album, it’s best to clear up a few things.

When most think of the last 20 years of Wanda Jackson’s career, and her return to secular music after a decade doing songs of praise, it is often more in consideration of the producers and collaborators who aided and abetted her mission to raise hell. The latest of these is the just-released “Encore,” produced by Joan Jett and Kenny Laguna and released on their Blackheart label in partnership with Nashville’s Big Machine.

More from Variety

Jack White Combines Anglophilia With Vinyl-philia as Third Man Records Prepares to Open London Shop

Miley Cyrus Goes Blonde-on-Blondie-er on 'Plastic Hearts': Album Review

Preceding this was a run of albums that included “Heart Trouble,” from 2003, with contributions from Rosie Flores, Elvis Costello and the Cramps; the brash, Jack White-produced “The Party Ain’t Over” (2011); and the spare, soulful “Unfinished Business” (2012), produced by Justin Townes Earle. With any of these, the temptation is there to focus on the younger makers, rather than their wiser mistress.

Make no mistake, however: Wanda Jackson is the boss – soft spoken at 83, yet commanding – and has been since her major label start, making singles for Decca in 1954, then albums for Capitol beginning in 1958, always blending country sides with rockabilly tracks.

“There was a time when you had managers, assistants, stylists telling you what to wear and how to wear it, but musically, I had final say,” says Jackson, in a gravelly voice ever-so-slightly roughed-up by Oklahoma City’s allergy season. “That’s how I got to rockabilly in the first place, when everyone thought I would exclusively be a country artist – which I was, too. I crossed the line, and they didn’t know what to do with me. But that’s what made me me… I was a maverick in that sense.”

That me, especially on self-penned songs of the late ’50s such as “Mean Mean Man,” “Baby Loves Him” and “Cool Love,” found a far-ahead-of-her-time Jackson ripe with rude innuendo and aggressive sexuality, to say nothing of her frisky vocals’ rasp.

At a time in post-WWII America when country and pop were filled with men commanding women to be demure and sing sexlessly — and when the Grand Ole Opry was a model of purity — Wanda Jackson was unceasing in her command of primal rock ‘n’ roll with hyper-passionate sensuality attached (and a band that dared to feature a Black pianist, Big Al Downing, in the segregated South).

If Wanda didn’t call herself a maverick, Joan Jett certainly would.

“Wanda is a unique and original pioneer,” says Jett. “I know how hard it was for me to negotiate the waters, as a woman in a male-dominated world, so I was in awe, imagining the hurdles that Wanda must have encountered doing her music at the very beginning of rock ‘n’ roll. There was no blueprint. Her sound was raw and incredibly soulful. Even the boys, then, were meeting resistance from the mainstream. And yet Wanda endured and had a career that lasted decades and influenced so many that came after her. She is strong, and she knows who she is.”

Courtesy Big Machine

“Encore” co-producer Kenny Laguna laughs when recalling their first studio sessions.

“I remember Wanda telling me, ‘No. That’s not going to happen. Not for me,’ and I’m like, ‘Lady, I’m here to help you.’ But Wanda is very strong, very definite, in what she will do and what she won’t — hat she’ll sing, and what she won’t. She’s got balls. She’s nobody’s puppet. Like Joan.”

Moving backwards, for a moment, to the time in the ’70s and ’80s when she moved into sacred song (“Music is about ministering to people; even love songs,” she says), Jackson teases about how people “didn’t know if I was alive or dead until I came back to secular music. But it was God’s will for me to come back to that.”

Upon her return, Jackson was keen to work with collaborators who could enhance the energy of who she knew she was, while showing off aspects of herself she hardly knew existed. “That’s always been the most exciting part, the most challenging part — not knowing what they’re going to bring out of me.”

In particular, Jackson laughs about working with Jack White on the twangy, tangy “The Party Ain’t Over,” saying, “I just love that guy. He could be my son. I didn’t know what was going to happen next with him. I learned to jump in and try different things. That was the fun part. I was afraid I wasn’t going to be able to live up to what he wanted, but apparently I did so, and then some.”

Jackson goes on to say, “Older people tend to get stuck, like in a rocking chair. You need younger people like Jack and Joan to throw you out of your comfortable place. Get you out of the chair. I surround myself with young people for that reason, for their ideas. It’s like having a cattle prod around.”

Discussing her retirement from touring in 2019 after the 2017 passing of her beloved husband and manager Wendell Goodman, Jackson suggests that she wasn’t quite done with making music, even if she was finished with the road. The young person/cattle prod who got Jackson moving toward new music — even writing new songs — was Wanda’s granddaughter and new manager, Jordan Simpson.

“She wanted a career in music, but behind the scenes, and she has made a name for herself working as an assistant and stylist for Maren Morris,” says Jackson. ”She said, ‘Maw, you’re too good a songwriter to not to be doing so anymore.’ She suggested setting me up with several newer country songwriters to have writing sessions.”

As Jackson has always written solo, without another song scribe before, this challenge excited her. “Save for my husband on a few songs, writing with someone else was a new sensation and, I might add, a wonderful experience.”

Afraid that hit country songwriters Will Hoge, Angaleena Presley, Luke Laird and Lori McKenna might have said “Wanda who?,” Jackson was pleased as punch that each artist seemed honored to write with her while quizzing her about the minutia of the old-school country music business. “We talked a lot about my life and the business back in the day, and as we did, song ideas and titles would come to the surface,” says Jackson. “I had questions about the new ways as well.”

Talking with Jackson about her husband, Wendell, for their collaborative tale with Wanda, “That’s What Love Is,” Laird, McKenna and Simpson concocted a life-sized story of a whirlwind romance. “Wendell was still alive when we wrote this, and I can remember when I first played it for him,” notes Jackson. “I told him, ‘I want to do a song written just about you and me. See if you agree with this.’ So I sang this song, and tears began coming out of his eyes. He couldn’t help it. The first verse of that song is how he would wake me up every morning. I sometimes like to sleep in, later than him – till noon if he let me – and he would wake me up with something silly and roll the blinds all the way open. I’d get mad, he’d give me coffee, then everything would be all right.”

Laguna, the co-producer of “Encore” with Jett, was quick to express his deep and abiding love for the Wanda-and-Wendell relationship song. “It’s my favorite track on the record, it’s so emotional. And the way she sings it. Wow. That and ‘Two Shots,’ which is on the other side, totally tongue-in-cheek.”

Another song that tells a true tale of man and wife is Jackson’s co-write with Vanessa Olivarez and Will Hoge, “We Gotta Stop.” Wanda admits that this story was far less pleasant to tell, one where several years into their marriage, “trouble was brewing regarding jealousy,” she says. “When I played, some audiences were more fun, and I guess you could say I was flirting with them. When I got off the stage, guys wanted to take their pictures with me, with their arms around me. I thought nothing of it, but it bothered Wendell. So we talked about it, being birds in a cage, and nothing more was said, and this song is about how we settled that.”

Courtesy Big Machine

Along with being excited about this new songwriting process, confessional or cheerful, Jackson is thrilled that her own song stylings and subject matter of the past — always ahead of their time — sound fresh and au courant on “Encore.”

“I guess everybody caught up with me,” she says with a laugh.

As he had done in connecting her with Jack White and Justin Townes Earle, Jackson’s publicist, the late Jon Hensley, suggested Jett, along with the possibility of a duets album and further explorations into other writers’ songs. “Joan and Kenny weren’t interested in that, but rather producing a new album of original songs on their Blackheart label,” says Jackson. “That sounded good, and it was going to be this independent album, until Big Machine got interested and wanted to partner for distribution. I feel very privileged.”

Says Laguna, Jetts longtime label and production partner, “We do very well with Joan Jett music, and stuff like L7, but listening to Wanda’s record, we knew that it had life in formats beyond that… like country. (Big Machine president-CEO) Scott Borchetta loved this record.”

Laguna recalls that the Kentucky-raised, Nashville-dwelling Hensley was a “visionary guy” who had a knack and an ear for original ideas when it came to his client, Jackson. “Jon got the ball rolling on this with us like six, seven years ago,” says Laguna. “We knew that Wanda was the start of it all, the beginning of pure rock ‘n’ roll. That’s the thing that Joan does, so seeing how she and Wanda might think and act alike was key — you either live it and feel it, or you don’t. You can’t fake it.”

Getting close, too, to Wanda’s husband Wendell (“They had never spent a night apart since 1958,” says Laguna) was essential to the Blackheart team. But Jackson and the Jett/Laguna pairing had to go through several heartbreaking tragedies as they worked on “Encore,” including the accidental death of Henley, as well as Goodman’s passing from a heart attack after one of Wanda’s gigs in Berlin. “It appeared, for a moment, that the record wouldn’t happen. Then, suddenly Wanda’s granddaughter helped bring her grandmother alive by starting more songwriting sessions together. It’s a miracle it all came together.”

Jett reminds Variety that she doesn’t often produce other artists. “Wanda is certainly an artist I’m thrilled to have worked with, and even more, to have gotten to know,” she says. “My main goal in producing Wanda was to create music that was a linear continuation of the original, pure rock ‘n’ roll which she help invent. At the same time, I wanted the music to be modern enough to reflect the decades of growth of that music. Pure rock ‘n’ roll is in your soul. It is intangible. Wanda has that in her. It is something that you can’t fake. In that, Wanda and I see eye to eye. I humbly think we have accomplished that mission.”

With this endeavor completed at last, a label such as Big Machine behind her, a voice that still throws fire and shade, and the excitement of collaborative songwriting still a new thrill, could Wanda Jackson’s “Encore” get an encore?

Jackson takes a long pause, and answers that she thinks of “Encore” as more of a victory lap than a last will and testament. “We never know what the future will hold, so why think of it as a last record?” she asks. “I’ve always said that I was in it for the long haul, and if Willie Nelson can keep singing at our age, I guess I can too. I fought a good fight, I won the long race and this is my victory lap.”

Best of Variety

Sign up for Variety’s Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.