How the Warner Brothers Got Their Film Business Started

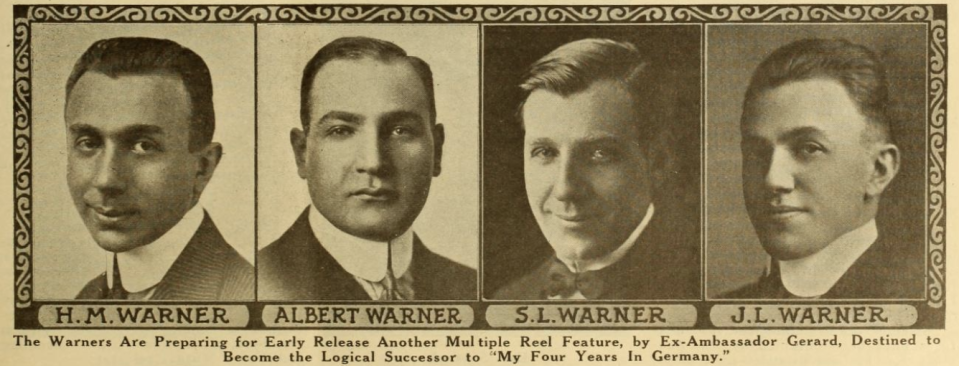

The Warner brothers — Harry, Sam, Albert and Jack — were different from Hollywood’s other movie moguls in the industry’s early years. They were shrewd, brash, outspoken and passionate in ways that deviated from the industry norm. The most publicly consistent brother was Harry, a stoic businessman and proud immigrant. Sam was the technical visionary who was gone too soon. Albert largely avoided the public eye, although he served as a loyal ambassador to the family brand. Jack was the wild child, the entertainer, the sometimes unpredictable one.

Those talents served them well during a transitional time for what would become the filmed entertainment industry. The year 1903 marked that transition, moving from what historian Tom Gunning calls a “cinema of attractions,” based on simple spectatorship of an event, to narrative storytelling, which allowed audiences to get lost in what they saw onscreen. There was only one way to test the viability of this new trend: with an audi-ence.

More from The Hollywood Reporter

What Studio Franchises Can Learn From the Rise, Fall and Rise of the Western

Can Movie Theaters Survive? It's the Most Enduring Question in Hollywood

Revisiting a Hollywood Crew's Archival Effort to Use Film to Convict Nazis at Nuremberg

Sam Warner pitched the idea of investing in this new technology to his family. The projector cost $1,000, and it came with a copy of Edwin S. Porter’s The Great Train Robbery (1903). The brothers pooled all their money, but it was not enough. Their father, Benjamin Warner, hocked his gold watch to make up the difference.

The brothers set up a tent in their yard and invited neighbors and community members to witness the moving images emanating from Sam’s projector. The attraction was a hit. Now the brothers needed a more per-manent venue. Knowing that a carnival was coming to the town of Niles, northwest of Youngstown, Ohio, they found a vacant store there and set up shop, hoping to take advantage of the influx of people attracted by the carnival.

Albert (still called “Abe” by the family) sold tickets, and Sam worked the projector. There are conflicting reports regarding the whereabouts of Harry and Jack. According to the family history, Harry stayed in Youngstown and worked to ensure that the family had an income. Jack was still quite young, and he may or may not have tagged along to Niles.

A history written by a Youngstown native claimed that Harry and Jack were also in Niles, with Harry tending to the finances and Jack running errands. During the shows, the 700 feet of tattered celluloid often broke or completely unraveled, but Sam quickly learned how to repair the film and stay on schedule. The Warners’ show was a hit, being the first film ever projected in Niles. Curious crowds filled the venue, proving the via-bility of a small cinema.

Once the carnival left Niles, Sam and Abe presented their show in other nearby towns until a massive snowstorm discouraged customers, who were unwilling to stand in the drafty and often unheated storefront theaters. The brothers had made $300 per week while on the road, after expenses. Harry recognized that the key to making a real profit was to lease their own venue and build a following. The brothers quickly found a former New Castle nick-elodeon spacious enough to show films.

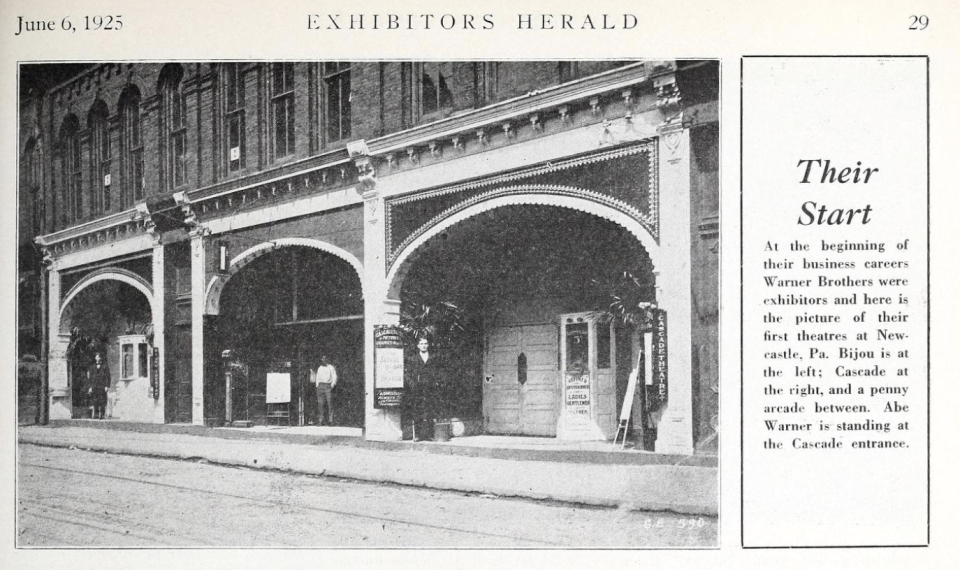

As the story goes, the brothers ran out of money before they could purchase chairs for their theater, so they worked out a deal with a local funeral parlor to use its seats, provided they were not needed for a funeral. The theater seated 99; keeping the capacity under 100 meant avoiding costly safety regulations such as fire extinguishers and emergency exits. Soon the brothers were running two theaters, the Cascade and the Bijou, which sat on opposite sides of a penny arcade, just a short trolley ride from the Warner home.

The Cascade opened on May 28, 1905. On Memorial Day, a funeral for the local school superintendent was scheduled, which meant the funeral parlor needed its seats. Desperate to keep their operation running through the holiday, the brothers called the superintendent’s widow and promised that if she postponed the service until the next day, her children could see free films all year. She agreed. The Cascade was an early success, both attracting the blue-collar community and offering a classy environment not yet associated with movie theaters, which were often located in the seedy areas of big cities. A sign outside the Warners’ venue read: “Refined Entertainment for Ladies, Gentlemen and Children.” Every woman who came to the theater was given a carnation. The Warners made filmgoing something of a social event.

Before the film started, Sam opened the show with some informative slides for the audience. The first stated, “Please read the titles [to] yourself. Loud reading annoys your neighbors.” This was followed by “Ladies! Kindly remove your hats” and “Gentlemen! Please don’t spit on the floor.” When the first reel of the film ended, a slide appeared reading, “One moment please while the operator changes reels.”

Ben Warner was proud that his sons had brought this new cinema technology to the community, but he was even prouder when, on the second day of operation, there was a line down the block as patrons waited to see the show. Ben and Pearl closed the store for the day and watched the spectacle. After the first show, the audience was so stunned that no one stood up to leave when the house lights were turned on. In another well-known piece of Warner history, Ben encouraged Jack to get up and sing his terrible version of “Sweet Adeline.” “Jack’s voice, skipping octaves from tenor to baritone, sounded like ice cracking from a glacial floe and drove customers from the place.” Sister Rose accompanied him on the piano, which she also played during film screenings.

The brothers capitalized on the period from 1895 to 1905, when nickelodeons made the transition from sideshows in saloons and amusement parks to main attractions. The timing was perfect to take advantage of cinema’s improving social status. Movies became most popular outside of major cities, where traditional theater had less of a financial foothold on audiences.

In rural areas and smaller cities, nickelodeons and storefront theaters took off. In nearby Pittsburgh, vaudeville mogul Harry Davis became interested in the nascent motion picture industry, and he opened the Nickelodeon on Smithfield Street. Given Pittsburgh’s prosperity, Davis’s operation benefited from the community’s disposable income. By the end of 1905, “movies were not simply gathering places … they were centers of communication and cultural diffusion.” The Warners’ Cascade theater followed the trend by combining movies with vaudeville performances.

The early film business could be extremely dangerous, especially during an era when smoking was commonplace. As the film wound through the projector, it did not wind up onto another reel (that would come later). Instead, the film piled up on the floor or in a bin. In his autobiography, Jack relates a story about a safety inspector who had been advised not to smoke around the highly flammable celluloid but walked into the projection room with a lit cigarette. “There was a rumbling blast that blew part of the projector through the ceiling and into the sky. The windows and doors collapsed, and the unfortunate inspector was dead when we finally dragged him, clothes ablaze, out into the air.” Jack always had a penchant for the hyperbolic, but the story is a good reminder of the risky nature of early film exhibition.

By 1907, the term “nickel madness” described both the widespread popularity and the broad disapproval of these five-cent cinemas. Some concerned citizens feared that these small theaters were ripe venues for pickpockets, while others were worried about moving images corrupting youth. Some thought that sitting in a dark theater was a “cloak for evil,” and in fact, in some theaters customers sat in the light and watched the movie through holes in a curtain. New York City police commissioner Theodore A. Bingham “denounced nickel madness as pernicious, demoralizing, and a direct menace to the young.” Trying to grow a business in the midst of such rhetoric would prepare the Warner brothers to deal with industry censors and moral crusaders.

The years following 1907 were momentous for the Warner family, both personally and professionally. Harry met his future wife, Rea Levinson, at a local dance. Harry was quite the dancer, having entered a series of dance contests with his sister, Rose. Like Harry, Rea came from a Jewish immigrant family, but her lineage was more intellectual, educated and cultured. Unlike many Hollywood moguls, Harry married only once and remained with Rea until his death. In 1908, Abe met a Jewish girl named Bessie Krieger, and they married shortly thereafter.

As nickelodeons popped up in nearly every town, demand for films skyrocketed, and audiences were eager for new content. Harry quickly realized that the real money was in film distribution. The brothers went to Pittsburgh and opened the Duquesne Amusement Supply Company, named after a local college in the hope of adding a touch of class to the business. Sam and Abe went to New York City and acquired films from theater magnate Marcus Loew.

The future top man at MGM studios, Loew sold the brothers a backlog of used films for $500. While the three older brothers were increasingly busy with their film ventures, poor Jack was still relegated to kid brother status, but he would soon get his break in the family business.

For the next 15 years, the brothers would rise and fall in the film business, always persistent and never giving up. Even when Thomas Edison sent his thugs to intimidate the brothers into patent submission, they never backed down.

The brothers began producing their own films and moved the operation to Los Angeles in 1917. From there, they operated in multiple locations, one near the Selig Zoo, and eventually at the famous Sunset Bronson Studios (now owned by Netflix). The brothers, who had been using the Warner Bros. name at least since 1920, took their next step.

At the end of 1922, the Warners filed for a new trademark: “Warner Brothers’ Classics of the Screen.” Harry said the trademark was meant to set the brothers apart from other film production companies, which were too numerous to count. Harry assured audiences that Warner films were “distinctly individual in production and story value, and in excellence of screen players.”

The studio was incorporated on April 4, 1923. The Roaring ’20s would define the Warners as fearless innovators, social crusaders and solidify the brothers as titans of this iconic American industry.

This column was excerpted from the forthcoming book The Warner Brothers (University Press of Kentucky, Sept. 5, 2023).

Best of The Hollywood Reporter