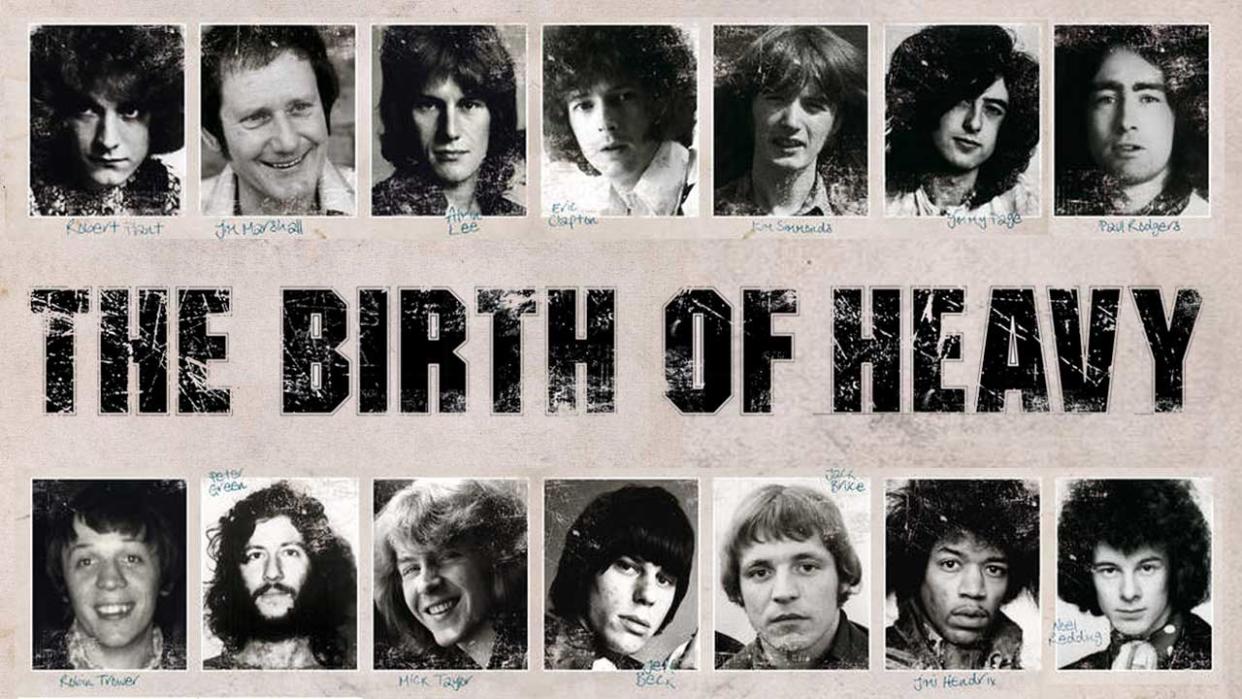

"There were guitar players weeping. They had to mop the floor up": How Jimi Hendrix invented everything we love

Like all the great overnight sensations, Jimi Hendrix took years to get off the ground. His was a long road to fame: from the little boy who in 1958 used his beat-up guitar to imitate TV cartoon sound effects, to the 1964 guitar slinger who hired out his talents to Little Richard, the Isley Brothers and others, to the outlandish psychedelic six-string shaman who flew into London in late 1966.

However, within weeks of Hendrix being unveiled to London’s goggle-eyed media at the Bag O’Nails club on Friday November 25, 1966, virtually every major British blues guitarist found himself rethinking his musical direction. Inevitably, the purists would continue to recycle the past, and the unimaginative would slavishly emulate Hendrix. But a handful of inspired innovators would choose to instead fashion their own unique styles, and eventually out of that seething maelstrom.

November 25, 1966

Having created a buzz with a handful of small-venue appearances, including the now legendary jam with Cream at Regent Street Polytechnic that had left Eric Clapton gobsmacked at his prowess, Jimi Hendrix was officially unveiled with a showcase gig in the Bag O’Nails, a tiny but influential music-biz Mecca in London’s Soho.

As well as key journalists invited by Hendrix’s manager Chas Chandler, a Bag O’Nails appearance ensured that the fledgeling Jimi Hendrix Experience would be seen by the venue’s regular clientele, which included Paul McCartney, The Who, Eric Burdon and other stars.

John Mayall (The Bluesbreakers): When Jimi first came to England, Chas Chandler had put the word out that he’d found this phenomenal guitar player in New York, and he could play the guitar behind his head and with his teeth and everything. The buzz was out before Jimi had even been seen here, so people were anticipating his performance. And he more than lived up to what we were expecting.

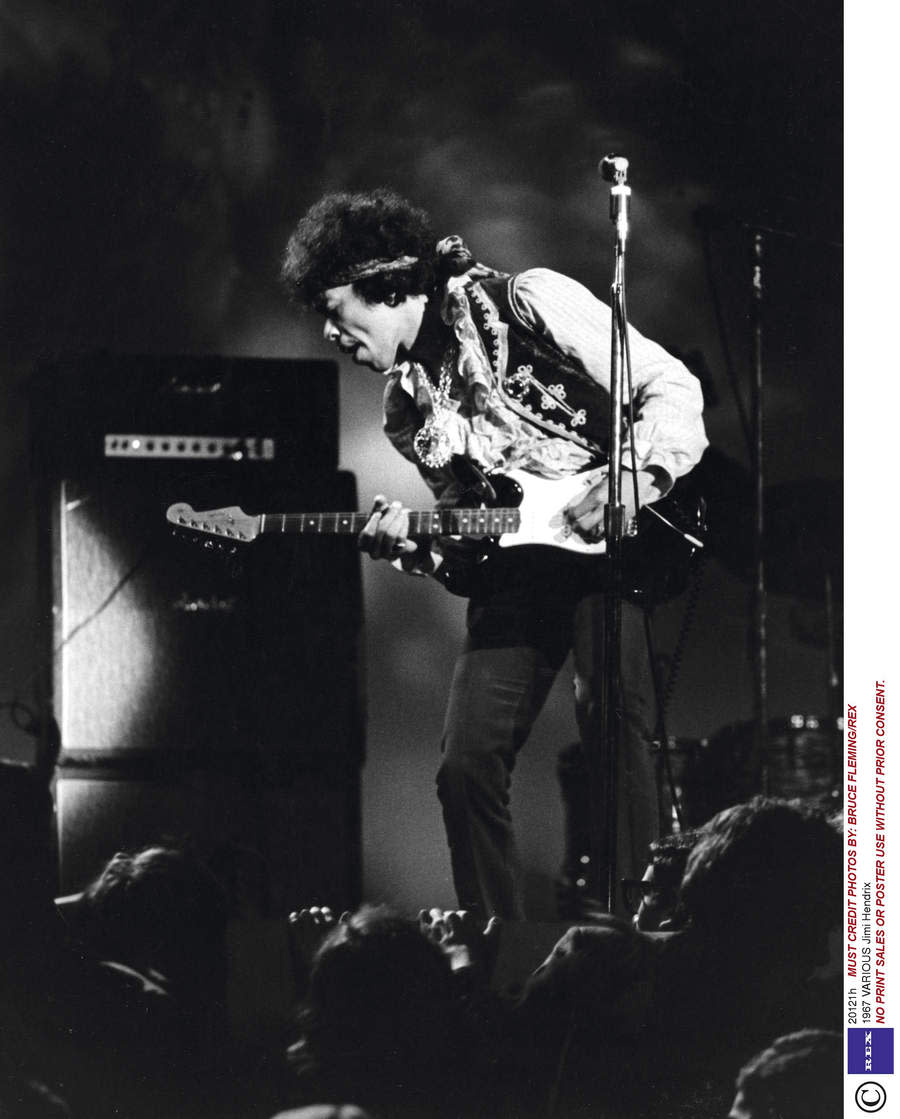

Terry Reid (vocalist): We were all hanging out at the Bag O’Nails – Keith, Mick Jagger. Brian [Jones] comes skipping through, like all happy about something. Paul McCartney walks in. Jeff Beck walks in. Jimmy Page. [Ed’s note: Page denies having been there.] I thought: “What’s this? A bloody convention or something?” Here comes Jim, in one of his military jackets, hair all over the place, pulls out this left-handed Stratocaster, beat to hell, looks like he’s been chopping wood with it. And he gets up, all soft-spoken, and all of a sudden, ‘WHOOORRRAAAWWRR!’ and he breaks into Wild Thing, and it was all over. There were guitar players weeping. They had to mop the floor up. He was piling it on, solo after solo. I could see everyone’s fillings falling out. When he finished, it was silence. Nobody knew what to do. Everybody was dumbstruck, completely in shock.

Keith Altham (journalist, NME): Jimi was almost too much, to be absolutely honest. He was overwhelming in that small space. You knew something special was going on, you knew the guy was obviously a brilliant guitarist, but it was very difficult to take in as a journalist.

Jeff Beck: The thing I noticed was not only his amazing blues, but his physical assault on the guitar. His actions were all of one accord, an explosive package. Me, Eric and Jimmy, we were cursed because we were from Surrey; we all looked like we’d walked out of a Burton’s shop window. He hit me like an earthquake when he arrived. I had to think long and hard about what I did next.

Mick Jagger: I loved Jimi Hendrix from the beginning. The moment I saw him, I thought he was fantastic. I was an instant convert. Mister Jimi Hendrix is the best thing I’ve ever seen. It was exciting, sexy, interesting. He didn’t have a very good voice, but made up for it with his guitar.

For almost half a decade, Hendrix had criss-crossed America, honing his talents as a sideman and studio guitarist, racking up credits with Little Richard, the Isley Brothers, Sam Cooke and many others. His was an impressive résumé, but fame and fortune hardly seemed any closer to him in 1966 than they did at the start of the decade.

In the autumn of 1966, Chas Chandler, previously best known as the bassist with The Animals, had ‘discovered’ Hendrix playing in a Greenwich Village club during a night out in New York, and immediately decided to bring him to the UK. Chandler’s instincts were absolutely right. Not only would Hendrix’s musicianship and image make him stand out from London’s guitarist elite, but had he remained in America, it’s very likely that he would never have got his head above water.

John Lee Hooker: Eric Clapton, John Mayall and all those other people over in England made the blues a big thing. In the States, people didn’t want to know.

Tony Garland (assistant to Chas Chandler): White America was listening to Doris Day. Black American music got nowhere near white AM radio. Jimi was too white for black radio. Here [the UK], there were a lot of white guys listening to blues from America and wanting to sound like their heroes.

Stephen Dale Petit (contemporary blues guitarist/genre expert): The British contribution to the blues is equal, in my eyes, to what Robert Johnson or Blind Lemon Jefferson did – all of those guys through to Muddy Waters. I think it’s a certainty that without the British blues boom the music would not have anything remotely like the profile it does. Remember too that when Chas invited Jimi to London, Jimi did not ask about money or contracts, he asked if Chas would introduce him to Beck and Clapton.

Using his extensive network of contacts, Chandler had engineered a huge profile for Hendrix since the day he arrived in London, but from November 1966 he shifted into overdrive. In the next two months, Jimi would play at the Marquee, the Cromwellian, Blaises, the Speakeasy and elsewhere, with London’s rock elite regularly turning out to hear him.

Any musician who hadn’t heard of Hendrix after that launch at the Bag O’Nails would know him now, and already his influence was being seen as well as heard; two weeks after the Bag O’Nails gig, when Cream played at the Marquee club, Clapton was sporting a frizzy perm, and he left his guitar leaning against his speaker cabinet, feeding back just as he’d seen Jimi do.

Late November 1966

Hendrix jams with organist Brian Auger at the Cromwellian. This is reputedly the first gig at which Jimi played through Marshall equipment.

Andy Summers (guitarist with Zoot Money and The Police): He had a white Strat, and as I walked in he had it in his mouth. He had a huge Afro, and he had on a sort of buckskin jacket with fringes that were to the floor. Yeah, it was intense and it was really great. It kind of turned all the guitarists in London upside-down.

December 13, 1966

The Jimi Hendrix Experience tape Hey Joe for popular TV show Ready Steady Go! Watching is effects wizard Roger Mayer, who’d already built custom fuzz boxes for Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, and would soon give Hendrix the Octavia octave-doubling device heard at the end of Purple Haze.

Roger Mayer: I said: “Damn, this guy is incredible.” He was the epitome of what any rock guitarist should be – we had no one of that calibre.

December 16, 1966

Hey Joe is released. It will peak at No.6 during its 11 weeks on the singles chart. Stephen Dale Petit makes the valid observation that, for a black man steeped in blues tradition, the marketing of Jimi’s launch in the UK was as revolutionary as his music. “The idea that Hendrix was a psychedelic guitarist more than a blues guitarist was partly down to how he was packaged,” reasons Petit.

Dave Gregory (guitarist, XTC): I was fourteen. I’d been playing guitar for about three months when I heard Hey Joe. I thought it was a dirge – a soul singer with a doom-laden backing chorus. When I finally got hold of the forty-five some months later, I turned the disc over and found Stone Free on the B-side, which was another thing entirely – the wildest guitar playing I’d ever heard. I was so dazzled by his brilliance that I didn’t immediately identify his playing as blues.

Stephen Dale Petit: Psychedelia was the burgeoning trend, and Hendrix, in those flamboyant clothes, was a ready fit for it, so it’s not surprising lots of fans didn’t see him as a bluesman. But guys like Clapton and Beck would have known exactly where Hendrix was coming from. They realised Hendrix personified everything that every English blues musician aspired to. He was also their worst fear, because he wasn’t sixty years old and from the plantation, he was the same age as them. But what they’d learned second-hand, he had learned on the circuit, playing with the originals.

Jimi Hendrix: Blues, man. Blues. For me that’s the only music there is. Hey Joe is the blues version of a one-hundred-year-old cowboy song. Strictly speaking it isn’t such a commercial song, and I was amazed the number ended up so high in the charts.

Mike Vernon (British blues record producer): At the time, I never really thought of him as being a blues guitarist. The blues hardly needed a reboot, as it was already on its way with the help of Clapton, Peter Green etcetera. He was undeniably a refreshing change from all that had gone before him, although to some degree his antics were only extensions of early performers like Gatemouth Brown. But a blues guitarist? Mmm… Well, he certainly could play and sing the blues when he chose to, but really he was an innovator in what was to become the rock marketplace. To my way of thinking, more guitarists were influenced by Eric Clapton and Peter Green, and then Stevie Ray Vaughan, than by Jimi Hendrix.

Mark Knopfler: The first time I heard Hey Joe on the radio, I completely freaked and immediately ran out and bought the record. I didn’t even have a record player.

December 16, 1966

On the same day Hey Joe hits the shops, Hendrix plays at Chiselhurst Caves, London, where he first meets Roger Mayer, destined to play a major role in developing Jimi’s array of guitar effects units.

Roger Mayer: I went there and brought some of my devices, such as the Octavia. I’d shown it to Jimmy Page, but he thought it was too far out. Jimi said, the moment we met: “Yeah, I’d like to try that stuff.”

December 21, 1966

The Jimi Hendrix Experience play at Blaises Club, London.

Chris Welch (reviewer, Melody Maker): Jimi Hendrix, a fantastic American guitarist, blew the minds of the star-packed crowd who… heard Jimi’s trio blast through some beautiful sounds like Rock Me Baby, Third Stone From The Sun, Hey Joe and even an unusual version of The Troggs’ Wild Thing. Jimi has great stage presence, and an exceptional guitar technique which involved playing with his teeth on occasions and no hands at all on others! Jimi looks like becoming one of the big club names of ’67.

January 24, 1967

On their first appearance at the Marquee, London, the Jimi Hendrix Experience break the house record. Support band The Syn will later evolve into Yes.

Peter Banks (guitarist, The Syn/Yes): It was a very peculiar gig. All the Beatles were there, and the Rolling Stones. Clapton and Beck and every other guitar player in town came along and we had to play to all these people. They were waiting for Jimi Hendrix, but we had to play, come off and then play another set. So people were going: “Well, thank God they’ve gone.” Then we came back on again.

Eric Clapton: He definitely pulled the rug out from under Cream. I told people like Pete Townshend about him, and we’d go and see him.

Pete Townshend: The thing that really stunned Eric and me was the way he took what we did and made it better. And I really started to try to play. I thought I’d never, ever be as great as he is, but there’s certainly no reason now why I shouldn’t try. In fact I remember saying to Eric: “I’m going to play him off the stage one day.” But what Eric did was even more peculiar. He said: “Well, I’m going to pretend that I am Jimi Hendrix!”

January 29, 1967

The Who headline a gig at the Saville Theatre, London, supported by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, Koobas and Thoughts. In the audience are Eric Clapton and Jack Bruce of Cream, plus Brian May.

Brian May (guitarist, Queen): I’d heard the solo on Stone Free, and refused to believe that someone could actually play this. It had to be some kind of studio trickery, the way he talks to the guitar and the guitar talks back to him. I was already playing in a band called Smile, and I thought I was a reasonably good guitarist, so I knew it wasn’t possible. So I went to the Saville, determined to be a disbeliever. But I was swept off my feet. I thought: “This guy is the most astounding thing I’ve ever seen.” And he did the Stone Free solo live, absolutely perfectly. It was back to the drawing board for me.

Eric Clapton: I don’t think Jack [Bruce] had really taken him in before… and when Jack did see it that night, after the gig he went home and came up with the riff [for Sunshine Of Your Love]. It was strictly a dedication to Jimi. And then we wrote a song on top of it.

February 3, 1967

At Olympic Studios in London, with Eddie Kramer engineering, Hendrix completes the recording of Purple Haze, which includes his first use of Roger Mayer’s Octavia effects pedal.

Eddie Kramer (engineer): At the end of the song, the high-speed guitar you hear was actually an Octavia guitar overdub we recorded first at a slower speed, then played back on a higher speed. The panning at the end was done to accentuate the effect.

Roger Mayer: The basis was the blues, but the framework of the blues was too tight. We’d talk first about what he wanted the emotion of the song to be. What’s the vision? He would talk in colours, and my job was to give him the electronic palette which would engineer those colours so he could paint the canvas.

March 8, 1967

Hendrix plays at the Speakeasy, London.

Jeff Beck: For me, the first shockwave was Jimi Hendrix. That was the major thing that shook everybody up. Even though we’d all established ourselves as fairly safe in the guitar field, he came along and reset all of the rules in one evening. Next thing you know, Eric was moving ahead with Cream, and it was kicking off in big chunks.

March 23, 1967

As Purple Haze enters the UK chart, Hendrix visits the Selmer music shop in Central London, where Paul Kossoff, later the guitarist with Free, is working as a sales assistant.

Paul Kossoff: He had an odd look about him and smelled strange. He started playing some chord stuff, like in Little Wing, and the salesman looked at him and couldn’t believe it. Just seeing him really freaked me out. I just loved him to death. He was my hero.

May 11, 1967

Eric Clapton buys his first wah-wah pedal, at Manny’s guitar shop in New York City.

Eric Clapton (guitarist, Cream): They said that Jimi had one, and so that was enough for me. I had to have one too.

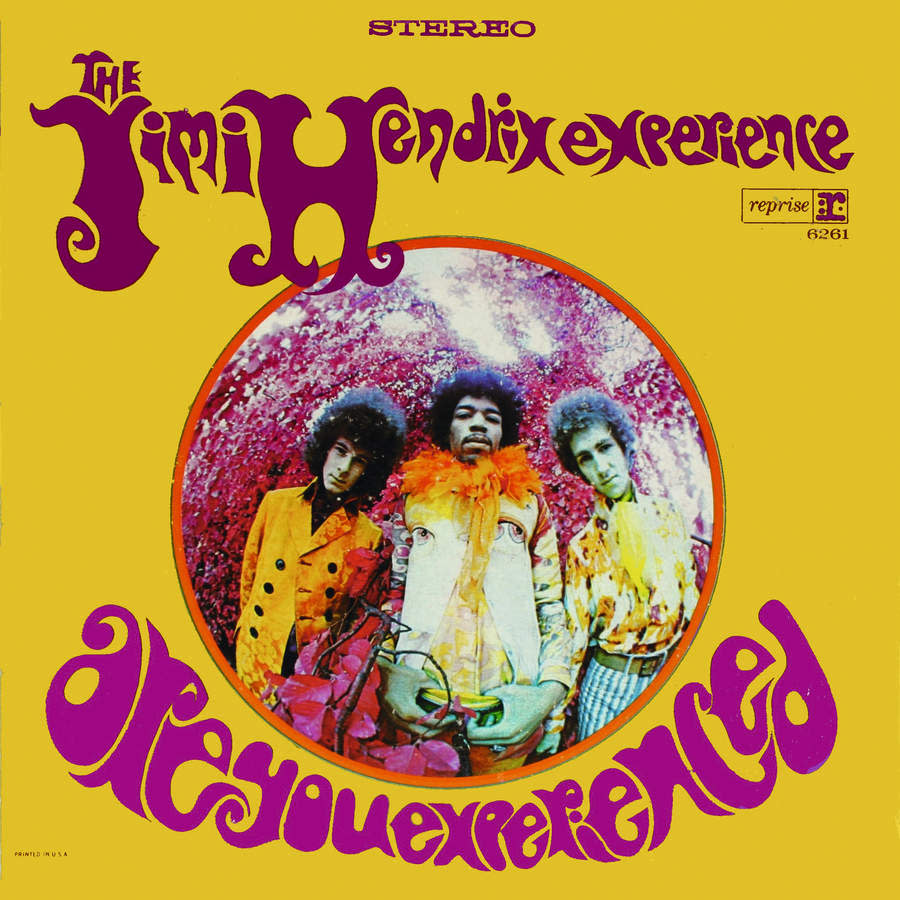

With the release of Hendrix’s debut album Are You Experienced, repeated plays made it possible for critics and fellow musicians to examine Hendrix’s oeuvre in greater depth. Now, aspects of his playing which had first seemed totally revolutionary could clearly be seen to have roots not just in traditional blues, but in British blues.

May 12, 1967

Are You Experienced is released in the UK. The album includes Foxy Lady, which includes a Jimmy Page riff lifted from the October 1966 single Happenings Ten Years Time Ago by The Yardbirds.

Stephen Dale Petit: Love Or Confusion takes a couple of British things, elements of The Beatles’ Tomorrow Never Knows and The Yardbirds’ Shapes Of Things, both of which use a home key, go down a step and then return to the home key. Using Marshall amplification, sonically and texturally Hendrix could sound very different than his influences and heroes, but the last three licks of the solo in Hey Joe clearly display the feel and the phrasing of Albert King. Stone Free exhibits the approach, attitude and composition – including melodic content and vibrato – of Hubert Sumlin. Generally, I hear Hubert Sumlin and Willie Johnson all through Hendrix’s playing – a clear line can be drawn from Willie Johnson, through Hendrix, to white blues-based hard rock and heavy metal.

Oe Satriani: Red House was a nod to his blues roots. I think the most underrated part of his playing is his sense of melody in everything he played, his way-in-the-pocket rhythm playing, and his combining of both into memorable parts that defined each song as a unique piece of music.

John Lee Hooker: I’ve always loved that song [Red House]. I loved the way Jimi did it. I never did see him play. I know he was seen as somebody in the rock side of things, but underneath he was a bluesman. He played a mean blues guitar.

Leslie West (guitarist, Mountain): I heard Hendrix playing Are You Experienced and I said: “What the fuck is this?” It blew my mind! The way he used that whammy bar? He’d knock those strings out of tune and then he’d stretch them right back into tune. The guy was unreal.

When Hendrix returned to the US, on June 18, 1967, to play at the Monterey festival, a new crop of American guitarists was exposed to the phenomenon for the first time. Mike Bloomfield, Johnny Winter, Stephen Stills and Billy Gibbons are just a few who subsequently acknowledged Hendrix’s powerful impact on them. Having achieved massive success at Monterey, Hendrix next began touring America.

June 18, 1967

The Jimi Hendrix Experience play at the Monterey International Pop Festival, Monterey, California.

Steve Miller (guitarist/bandleader): I was immediately amazed when he opened with Killing Floor. I had heard Wolf and Hubert play it so many times in Chicago. When I saw what Jimi did to it, it was as if what I had been trying to do for years suddenly became perfectly clear. I immediately understood what I had been longing and searching for.

August 9, 1967

The Jimi Hendrix Experience play at the Ambassador Theatre, Washington DC. In the audience is Nils Lofgren.

Nils Lofgren: When I saw Jimi Hendrix, I just was possessed. I realised: “Oh my god, this is what I want to do. It’s going to be my career.” And there was no turning back.

October 17, 1967

Jimi Hendrix jams with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, standing in briefly for Mick Taylor, at Klooks Kleek, London.

John Mayall: When he sat in with you, he would just fall right into whatever you were doing. He was just a natural musician, and I don’t think upstaging was any part of his persona. He loved to play, he dug music and he loved the attention he was getting.

Mick Taylor: I thought he was amazing. For a guitarist to have that energy in his playing, and also the control and the rhythm. You know, for most guitarists it’s incredibly difficult to play like that, or to even play anywhere near that standard in a three-piece group. I mean, Eric Clapton did it with Cream. And Hendrix was great the way he switched from rhythm to leads. His guitar and his voice were almost like the same thing.

If Hendrix was the trigger, one of the early heavy-blues bullets out of the gun was Cream’s second album, Disraeli Gears. Apsychedelic quantum leap ahead of their debut, sonically much heavier but still dominated by Clapton’s blues guitar solos, it delivered their US breakthrough, reaching No.4 on the Billboard chart.

November 3, 1967

Cream release Disraeli Gears.

Eric Clapton: We went off to America to record Disraeli Gears, which I thought was an incredibly good album. And when we got back, no one was interested because Are You Experienced had come out and wiped everybody else out, including us. Jimi had it sewn up. He’d taken the blues and made it incredibly cutting-edge. I was in awe of him.

December 15, 1967

The Who release The Who Sell Out.

Stephen Dale Petit: I think it was Jimi’s arrival that made a lead guitar player out of Pete Townshend, because when he got into his boilersuit era he was suddenly soloing, really flying, playing some amazing shit as a soloist, which he never did before.

February 10, 1968

The Jimi Hendrix Experience headline at the Shrine Auditorium, Los Angeles. Support band the Electric Flag feature guitarist Mike Bloomfield.

Mike Bloomfield: For years, all the [black guys] who’d make it into the white market made it through servility, like Fats Domino – a lovable, jolly, fat image – or they had been picked up by the white market. Now here’s this cat, you know: “I am, like, black and tough.”

May 10, 1968

Supported by Sly & The Family Stone and the Joshua Light Show, the Jimi Hendrix Experience play two shows at the Fillmore East, New York City.

Paul Stanley (guitarist, Kiss): I grew up going to Fillmore East, seeing Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Humble Pie. Hendrix was like somebody from another planet. God bless Stevie Ray Vaughan, but there wouldn’t be an SRV without a Hendrix.

July 17, 1968

Deep Purple release their debut album, Shades Of Deep Purple, which includes a cover of Hey Joe in the style of Hendrix.

Ritchie Blackmore (guitarist, Deep Purple): I was impressed by Hendrix. Not so much by his playing, as his attitude. He wasn’t a great player, but everything else about him was brilliant. Even the way he walked was amazing.

July 29, 1968

The Jeff Beck Group release their debut album, Truth. Along with Cream and Led Zeppelin, they would prove pivotal in taking rock into heavier territory and paving the way for heavy metal.

Al Kooper (songwriter, record producer and musician, and co-founder of Blood, Sweat & Tears): Rock My Plimsoul uses a quarter-note triplet turnaround which is very effective and the track bounces around. Beck sounds a lot like Hendrix on this.

As the 60s entered its final year, Hendrix was losing focus, but stunning debut albums by Led Zeppelin, Free, Taste and others confirmed that heavy blues was fast becoming the name of the game. This innovative form of blues eschewed authenticity, did not try to remain true to Mississippi or Chicago, and was more excited by the possibilities of creating a contemporary music that reflected the passions and interests of the rising generation.

January 12, 1969

Led Zeppelin release their self-titled debut album, which spends 73 weeks on the US Billboard chart and 79 in the UK. Its most obviously blues-oriented tracks are You Shook Me, I Can’t Quit You Baby and How Many More Times, but these were interwoven with intimations of what would become heavy metal and shades of art-rock, dragging the blues superstructure into pastures new. All of this was rendered aurally fresh by Page’s innovation of placing an extra microphone 20 feet away from the band to gather their ambient sound. Contemporary critics hated it, but time has proven this to have been a groundbreaking leap forward.

Jimmy Page: There were a lot of improvisations on the first album, but generally we were keeping everything cut and dried. Consequently, by the time we’d finished the first tour, the riffs which were coming out of these spaces, we were able to use for the immediate recording of the second album.

John Mayall: People like Jimmy Page, Gary Moore, Jeff Beck and several others, you could tell they were incorporating things that Jimi was doing into their music. His influence was very strong in that heavy-blues direction.

March 14, 1969

Free release their debut album, Tons Of Sobs. More minimal and less eclectic than Zeppelin’s debut, it was nevertheless another radical fusion of blues structures with hard-rock attitudes, delivering a vibrant attack to the band’s distinctively melodic songs.

Paul Rodgers (vocalist, Free): The songs I had written up to that point were blues songs. I looked around and I saw that everybody – the bands that had real credibility and meaning, somebody like Jimi Hendrix and Cream – was taking the blues to a different place. They were making it their own. I suppose Hendrix was almost like a psychedelic blues and Cream. Well, that’s what it was in a way – psychedelic blues. And I said to Paul [Kossoff, Free guitarist]: “That’s what we have to do – take what we have now and write our own songs and find our own identity, basically.” So it grew right out of the blues.

April 1, 1969

Taste, led by guitarist Rory Gallagher, release their self-titled debut album. Arguably the most traditionally blues-oriented album of this burgeoning new generation, Taste was nevertheless infused with the restless energy that was supercharging blues as the decade closed. Hendrix himself was evidently impressed, because when asked how it felt to be the greatest guitarist in the world, he’s said to have replied: “I don’t know, go ask Rory Gallagher.”

Rory Gallagher: Before Hendrix, Jeff Beck had distorted his guitar and so had Keith Richards, and there was distortion on the early-fifties blues records. They didn’t use it as a technique, but they had small amplifiers that were turned up very loud, and it became part and parcel of the Chicago blues sound. Hendrix trimmed it and made it into an art form.

July 1969

Leslie West releases his debut album, Mountain, a decidedly heavy-blues offering, clearly inspired by the Cream/ Hendrix power-trio format, and produced by Cream collaborator Felix Pappalardi, who also played bass.

Leslie West: Led Zeppelin, Cream and Hendrix were huge at that time. Being from New York, I was never into the San Francisco sound – the Dead, the Airplane and all that. But when these guys started coming over from England, a different world opened up. I mean, the Stones had great blues riffs in the mid-sixties, like Satisfaction, The Last Time. But when Cream and Hendrix came along, I knew it was time for me to start practising. Cream was probably the most influential on me. It was weird, because the British guys were imitating black American blues guys, and then we were imitating the British guys.

August 1969

Humble Pie release their debut album, As Safe As Yesterday Is.

Peter Frampton (guitarist, Humble Pie): Clapton’s blues style was very sophisticated and charming. Very ‘on the money’. Hendrix comes over. [His playing] wasn’t ugly, but it was more ballsy. A little out of tune, but it was full of passion. I think it’s his passion that I love most of all.

November 7, 1969

Hendrix is at the Record Plant studios in New York City, working on the tracks Izabella and Room Full Of Mirrors.

Leslie West: When we were recording Mountain Climbing in the Record Plant, Jimi was recording Band Of Gypsys in the next-door studio. So he came in and listened to Never In My Life, and he looked at me and said: “Nice riff, man.” He gave me a compliment. That was all I needed to hear.

John Mclaughlin: By the end of the 1960s, Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton had turned the rock’n’roll generation on its collective head. Of course, that would not have been possible without the music created by the great black blues players such as Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, Fred McDowell, Buddy Guy and the great BB King.

Jimi Hendrix died just months later, on September 18, 1970, but the heavy blues boom he initiated lived on and thrived. ZZ Top would release their first album in January 1971, the same year in which the Stones got noticeably heavier with Sticky Fingers. Kiss would unleash their debut in February 1974, and proof of the lasting appeal of heavy-blues music came with the emergence of Stevie Ray Vaughan in 1983 and Joe Bonamassa at the beginning of the new millennium.

Joe Bonamassa: I don’t think there’s any music that you hear on the radio today that would be possible without Jimi Hendrix.

Joe Satriani: He was the deepest blues player. He played the saddest stuff and he played the funniest. He played the most outside stuff, but it was really from the gut. He strayed from the traditional blues playing, yet he always seemed to incorporate the moans and the cries into a phrasing that was completely blues.

Slash: I think the attraction with Jimi was just that he had this uninhibited, fluid guitar style that basically screamed. It had this over-the-top sound to it that just kind of drew me in.

Stevie Ray Vaughan: I loved Jimi a lot. He was so much more than just a blues guitarist. He could do anything.

Jimi Hendrix: I’ve been imitated so well I’ve heard people copy my mistakes.

For more information on Jimi Hendrix, see the official website jimihendrix.com