"There were guitar players weeping, they had to mop the floor up. He was piling it on, solo after solo" – how Jimi Hendrix and Eric Clapton changed guitar forever

It would have been Jimi Hendrix's birthday today so to celebrate we're bringing you this archive piece - let's go back to the source...

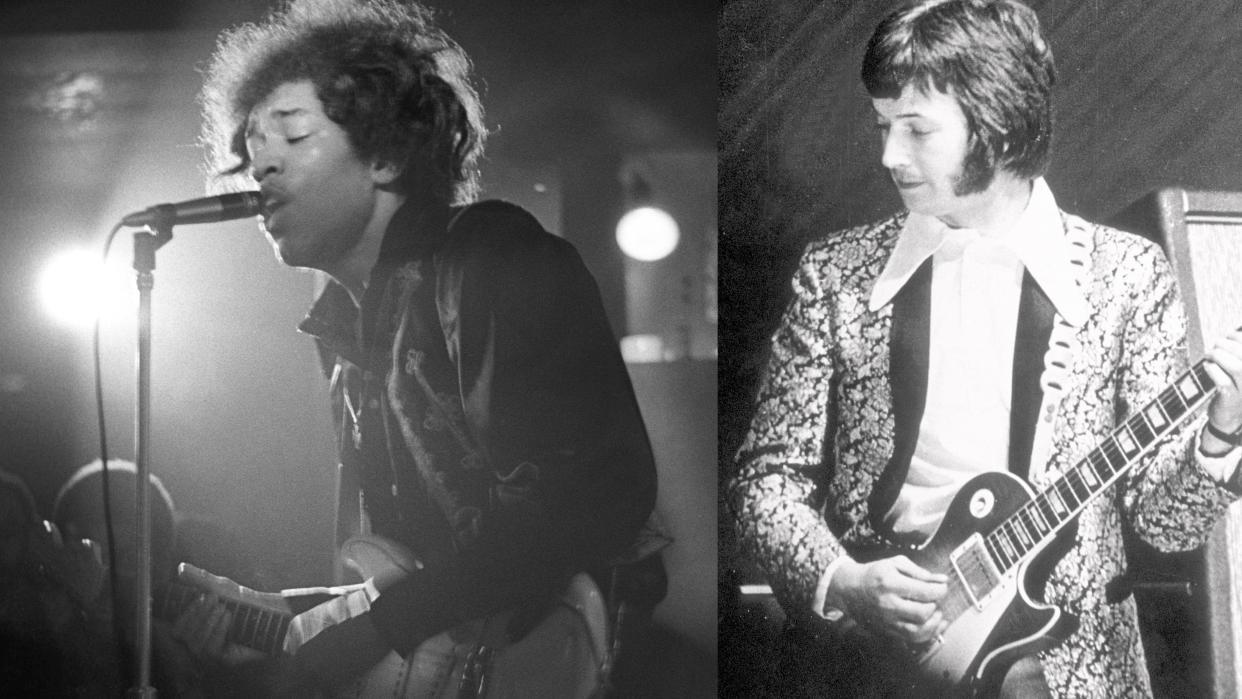

1 October 1966. Cream are playing at the Central London Polytechnic in Regent Street. Eric Clapton had left John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers in July, and since teaming up with bassist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker, Cream seemed invincible.

That three already well-established musicians should form a band was without precedent in British rock history. And, for Clapton, the powerhouse rhythm section of Bruce and Baker was the dream team. It allowed him the freedom to stretch out on long extended jams, an innovative format owing more to jazz than rock or blues - and the band had been taking audiences by storm.

Killing floor

An outsider jamming with Cream was unheard of, but, on this night, when manager Chas Chandler asked if new American guitarist Jimi Hendrix could sit in for a number, Clapton readily agreed.

Hendrix had only flown in from New York a week before, but thanks to Chandler’s clever PR, a huge buzz was already going around the London clubs.

[Hendrix] played Killing Floor, a number I always wanted to play but which I never had the complete technique to do

Clapton couldn’t have anticipated what was about to unfold. “He was very, very flash - even in the dressing room. He stood in front of the mirror combing his hair and asked if he could jam. He played Killing Floor, a Howlin’ Wolf number I’d always wanted to play but which I’d never had the complete technique to do.”

The effect on Clapton was undoubtedly cataclysmic, shattering any preconceptions about blues guitar - and his confidence. Writer Keith Altham was present. “Hendrix blew into Howlin’ Wolf’s Killing Floor at breakneck speed, just like that - stopped you in your tracks.”

Chas Chandler went backstage to find Clapton puffing nervously on a cigarette. “You never told me he was that fucking good,” Clapton is reported as saying. Chandler later recalled, “When we first met in New York, Jimi knew all about the guitarists in Britain and asked if he’d get to meet Eric Clapton. I told him that once he got over, he’d show Clapton how it was done, which of course he did.”

A night to remember

The Blues Band and The Manfreds guitarist Tom McGuinness first met Clapton at an audition at The Station Hotel in Richmond in 1963 and hit it off immediately via a mutual love of the blues.

“We sort of chatted and said names to each other like Elmore James and Lowell Fulson… the fact that you could meet someone who knew these people was a real treat.”

It was fine with the white rock ’n’ rollers until I heard Freddie King, then I was over the moon

McGuinness and Clapton formed a band, The Roosters, and it was during that time that Clapton first heard Freddie King.

“It was fine with the white rock ’n’ rollers until I heard Freddie King, then I was over the moon,” Clapton told Guitarist, speaking of his own musical development. “I knew that was where I belonged, finally. That was serious, proper guitar playing and I haven’t changed my mind ever since.”

Shortly afterwards, The Roosters disbanded, Clapton joined The Yardbirds and McGuinness went on to play with Manfred Mann.

“I didn’t see Eric play in between then and the Mayall album, because I was working every night,” says Tom.

“I was at a college gig in Manchester in 1966 and before the gig they were playing records while we were setting up and I heard this record and I thought, ‘Wow! Who is that amazing guitar player?’ and it was John Mayall’s new album [Blues Breakers With Eric Clapton] and I thought, ‘I didn’t know he was that good!’”

Flying with The Yardbirds

To those who knew him, Eric Clapton’s eventual evolution to godlike guitar playing status must have seemed a divine right. The genesis of his fame began with The Yardbirds, a band of neatly suited mods from south London. In the wake of The Rolling Stones, the band’s gigs at Richmond’s Star Hotel and Crawdaddy Club had fast become the stuff of legend.

Fronted by singer and harmonica player Keith Relf, The Yardbirds excelled at hammering out frenetic takes of R&B anthems by heroes such as Chuck Berry and Slim Harpo, culminating their shows with the guitarists speeding up the neck in a manic tour de force.

Sonny Boy put me on the spot at any possible occasion. It was just a nightmare and I asked for it

Replacing guitarist Top Topham, 18-year-old Eric Clapton had joined the band in October 1963, bringing about an immediate quantum leap in both The Yardbirds’ sound and fortunes. Shortly after, German promoter Horst Lippmann arranged for the hard drinking, maverick blues harmonica player Sonny Boy Williamson to work with the band.

A larger than life character, more used to the rigours of juke joints in his native Helena, Arkansas, Sonny Boy Williamson accompanied Lippmann to catch a Yardbirds show at Richmond’s Crawdaddy Club. After briefly jamming, he was enthusiastic at Lippmann’s suggestion that they should record.

On 8 December, Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky and engineer Keith Grant duly lugged gear into the club’s cramped kitchen for two nights of recording. As Clapton later admitted, backing the blues legend was a daunting prospect.

“He put us through some bloody hard paces. For a start, he expected us to know his tunes. He’d say, ‘We’re gonna do Fattening Frogs For Snakes, then kick it off, and, of course, some of the band had never heard those songs.

“I’d already decided before I met him [Sonny Boy], that he wasn’t one of the great blues artists; I think he sensed my arrogance and deliberately gave me a hard time. He put me on the spot at any possible occasion. It was just a nightmare and I asked for it.”

Listening to the album today, the band’s rhythms sound stilted, and Clapton’s solos on his Fiesta Red Telecaster, played through a Vox AC30, lack any fire.

Clapton lets loose

In March ’65, The Yardbirds’ single For Your Love was racing up the charts and, in a display of extraordinary idealism, Clapton left the band. “I got brainwashed with this commercial R&B. The whole thing got so businesslike with finances and promotion, we became machines instead of human beings,” he later said.

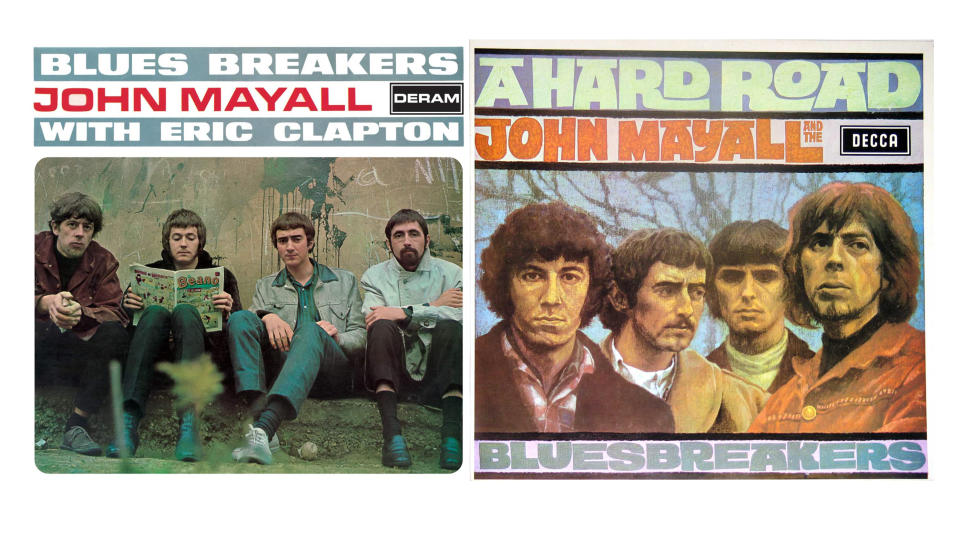

Over the next five years, fleeing fame and expectation would become an obvious character trait of Clapton’s, but little enticement was needed for him to join John Mayall & The Blues Breakers; Mayall was a blues purist, with an encyclopaedic knowledge of the music and a record collection to match.

With Jimmy Page producing, Mayall’s first move was to record two songs for Andrew Oldham’s Immediate label, I’m Your Witchdoctor and the smouldering slow paced Telephone Blues. With Page’s sympathetic ear at the mixing desk, Clapton was given free rein to reproduce his live sound, the sustained, disembodied wail of his Gibson Les Paul howling over Mayall’s droning Hammond organ.

Page’s white-coated engineer, more used to working with big bands and orchestras, at first switched off his machine, stating that the guitar was unrecordable. He was unable to believe Clapton was producing his sound on purpose!

Soft Machine guitarist John Etheridge remembers seeing Clapton play on many occasions during the mid-1960s.

“When [The Kinks’] You Really Got Me came out, Dave Davies’ solo was considered to be the pinnacle of what people were doing at the time. It was kind of Chuck Berry on amphetamines - lots of notes and double-stopping, early 60s bending. I’d heard Five Live Yardbirds and I thought, ‘This guy’s okay…’ but I didn’t think about it much.”

To the Manor born

But in October 1965, on the recommendation of a friend, Etheridge went to see the Blues Breakers at the Manor House in Finsbury Park.

“I walked in and there was this guy standing there and he began playing and the whole of my life went 'kryyykkk', really. The reason why it was so great was that this was the first time I had heard anyone actually singing on the guitar.

The Les Paul into the Marshall was just incredible. The whole room was transfixed; everybody was blown away

“The whole emphasis, the whole vocalisation of it, the self-conscious intelligence and musicality of it was in another league, really. The sounds of it - and the vibrato. I’d heard Buddy Guy and BB King, but they had the implication of vibrato and Clapton completely refined it. The Les Paul into the Marshall was just incredible. The whole room was transfixed; everybody was completely blown away.”

When John Mayall & The Blues Breakers went into Decca’s West Hampstead studio, their small budget landed them in the undersized No 2 studio. To compound matters, producer Mike Vernon and engineer Gus Dudgeon were both comparative rookies and, as Vernon later recalled, unprepared for the difficulties they would encounter:

“John didn’t know what the hell was going on as far as technical problems were concerned; he was just interested in making music. And Eric would insist on playing loud, which we hadn’t had to contend with before.”

Clapton, in fact, resolutely refused to turn down his Marshall JTM45 combo. “He had a terrible time with the engineer,” drummer Hughie Flint recalled.

“He wanted his amp right up, which meant it was distorting and Gus was tearing his hair out. But Eric said, ‘No, I can’t play unless I play like I play on stage.’”

Proximity mics

In an interview with Guitarist in 1994, Clapton elaborated: “When I was doing that album with John Mayall, it was obvious that if you mic’d the amp too close it would sound awful, so you had to put the mic a long way away and get the room sound of that amp breaking up.”

Fortunately, Clapton’s obstinacy on the recording of what has become known as ‘The Beano Album’ (due to Eric reading the comic in the cover shot) produced what is undoubtedly one of the most influential albums in rock history: one that’s inspired not only blues players, but just about every rock guitarist of note, from Eddie Van Halen to Steve Hackett.

The Blues Breakers record wasn't nearly as good as the live show. People used to be in tears

However, some people who had seen The Blues Breakers play live had a few mixed feelings. “We were disappointed with that record,” Etheridge continues. “It wasn’t nearly as good as the live show. People used to be in tears, because it was so beautiful and good; friends of mine would just be sobbing. That’s where ‘Clapton Is God’ came from. It wasn’t promo bullshit; he was!”

Clapton would leave the Blues Breakers two months later to form Cream. But with ‘Clapton Is God’ graffiti appearing on bus stops and walls around London, for John Mayall losing his star player was a bombshell.

He must have taken small satisfaction from the fact that Clapton helped create an album that ironically achieved higher chart success than Cream’s first record when it was released later that year.

Read more

But Clapton’s position as the greatest British blues guitarist seemed unassailable. “I was so deadly serious about what I was doing - I thought everyone else was either in it just to be on Top Of The Pops or Ready Steady Go! or to score girls or for some dodgy reason. I was in it to save the fucking world! I wanted to tell the world about blues or just get it right,” Eric said.

“I saw myself as being Buddy Guy, playing with a trio, but I was out of my depth with Jack and Ginger,” he later admitted privately. But whatever insecurities Clapton had about Cream - and he had some - they were soon compounded.

Hendrix has arrived

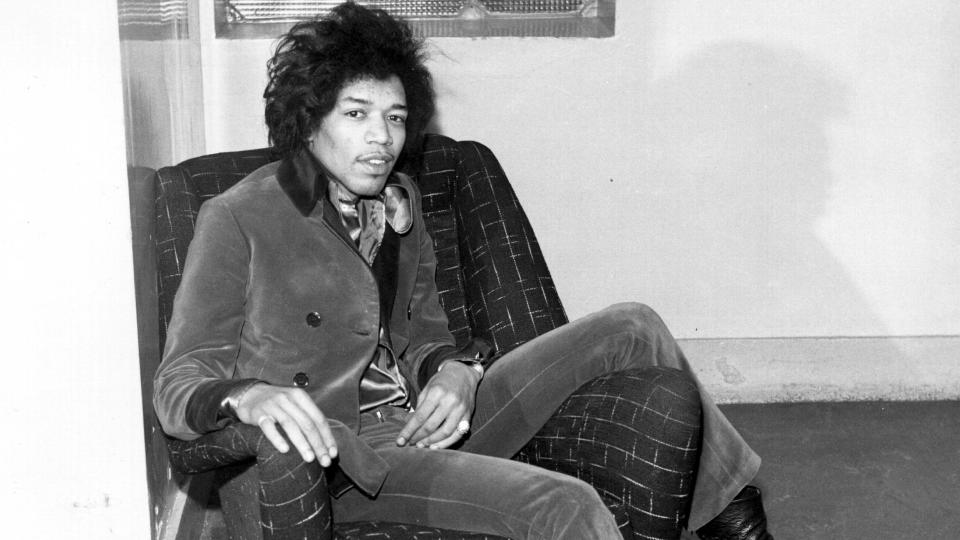

On Friday 25 November, the hurricane that was Jimi Hendrix finally hit. Manager Chas Chandler arranged a showcase gig at The Bag O’ Nails, a trendy Soho watering hole frequented by pop aristocracy such as Paul McCartney and The Rolling Stones.

A huge buzz was already starting about this American guitarist; nothing like him had been seen or heard before. Despite Clapton’s undoubted guitar playing skill, he was hardly a showman. He stood stock still studying his fretboard with academic intensity.

He hit me like an earthquake

Hendrix, on the other hand, used every trick in the book. Not only was his playing sensational, he was a consummate showman, picking his Fender Strat with his teeth, behind his back and humping it between his legs.

Hendrix was more than just a great musician, he was an American archetype, the latest in a lineage of hard-living, hard-rocking ramblers that included artists as musically diverse as Charlie Parker, Robert Johnson, Hank Williams and Jerry Lee Lewis: a lineage that stretched back to 1920s bluesman Charlie Patton.

Singer Terry Reid set the scene: “We were all hanging out at The Bag O’ Nails, Keith [Richards], Mick [Jagger], Brian [Jones] come skipping through, all happy about something. Paul McCartney walks in, Jeff Beck. I thought, ‘What’s this? A bloody convention or something?’

“Here comes Jimi, wearing one of his military jackets, hair all over the place, pulls out his left-handed Stratocaster, beats it to hell, looks like he’s been chopping wood with it. He gets up all soft spoken and, all of a sudden, Whooor-raaawwrr! and he breaks into Wild Thing… and it was all over.

“There were guitar players weeping, they had to mop the floor up. He was piling it on, solo after solo. I could see everyone’s fillings dropping out. When he finished there was silence. Nobody knew what to do, everyone was dumbstruck, completely in shock.”

Jeff Beck was similarly devastated. “It wasn’t just his amazing blues playing I noticed, but his physical assault on the guitar; it was an explosive package. He hit me like an earthquake. I had to think long and hard about what I should do next.”

The aftermath

The late Guitarist writer Julian Piper was also a witness to Jimi’s UK landing: “I’d also seen the cataclysmic effect of a Jimi Hendrix performance,” he recalled.

These were the glory days of pop journalism, and Melody Maker’s Chris Welch penned the ‘Raver’s Column’, a goldmine of trivia about who was jamming with whom, who’d been spotted creeping into a recording studio in downtown Penge, and who was about to throw in the towel in a famous band - that sort of thing. Welch was the man on the spot.

It was all very spontaneous, and when we went on stage we had no idea what we were going to do

“Sent to London for a week in 1966, I excitedly scanned ‘The Raver’. An entry read: ‘Eric Clapton, Paul McCartney and Brian Jones all hung out at Mayfair’s new 7 ? Club to catch sensational newly arrived American guitarist, Jimi Hendrix. Catch him next week on Wednesday or Thursday, he’s going to be big!’

“That Wednesday night,” Julian continues, “with a friend in tow, I stumbled downstairs to sit on a long bench at the edge of the dance floor. The cellar couldn’t have held more than 40 people, and occupying almost all of the floor were two Marshall stacks and a drum kit. More people drifted in and then - wearing one of his military jackets, his face dwarfed by a huge bush of hair - a smiling Hendrix walked on carrying a white Fender Strat.

“I was transfixed; I can’t recall even noticing the arrival of Noel Redding and Mitch Mitchell. After briefly fiddling with his tuners, Jimi kicked into Rock Me Baby, the sound knocking you back in disbelief - a shattering wall of glorious controlled noise, mixing feedback and Eastern tonalities, all built around that familiar, hoary old blues riff. As we later found out, at this point Jimi was struggling for enough suitable material, and the band barely rehearsed.”

Noel Redding provided an intriguing insight into that time: “We learned to play as we went along. Right at the beginning, it was very short, intense gigs at small clubs in London with The Beatles and The Rolling Stones watching, which really freaked me out.

“There were never any setlists and we didn’t do soundchecks or hardly any rehearsing. That’s why there were some tunes we never played live, because, if we did, they’d just peter out or collapse.

“We’d just tune up on stage, say good evening to the audience and probably kick off with Killing Floor. It was all very spontaneous, and when we went on stage we had no idea what we were going to do.”

Dare to be different

Julian Piper picked up the story: “Although the record was not yet out, Hendrix played Hey Joe and Stone Free, but the highlight was his take on Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone; somehow he managed to sing it and play all those wonderful doublestop licks from the original recording.

“At one point, he walked in our direction, leering - the guitar neck pointing suggestively at the face of the beautiful blonde girl sitting beside me, a person I realised was Marianne Faithfull. Beside her sat an expressionless Mick Jagger.

A few of them said they wanted to give up playing the guitar. They realised... that what they'd been doing was just a pale imitation

“After Jimi finished with his volcanic take on Killing Floor, he flung the Strat to the ground, creating a cacophony of feedback. Chas Chandler, who’d been sitting behind us, vaulted over to switch the amps off, leaving a stunned silence. An encore would have seemed redundant.”

Roger Mayer, who had been building effects pedals for Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck for several years (his Octavia pedal famously became a favourite of Jimi’s), also recalls the shocked aftermath:

“A few of them said they wanted to give up playing the guitar. They realised they’d seen someone so good that what they’d been doing was just a pale imitation of the real deal. That night exposed, in no uncertain terms, the weaknesses of their own guitar playing. It’s true of seeing any genius perform, and it showed the English guitar playing fraternity what could be done.

“In 1964, Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page had started rolling forward the guitar sound, but it wasn’t until Jimi that we really went to town. Up until then it had all been very simple - a white man’s version of the blues, which was all very good, but didn’t shift the goal posts.”

Looking forward

Jimi told me that was one of the reasons he got fired - he was always doing tricks, stealing the show

“Jimi was used to playing behind Wilson Pickett, where he’d get an eight-bar break in a song if he was lucky,” continues Mayer.

“He came from the tight confines of the R&B bands with the shiny suits and the headliners out front. They didn’t want anyone in the back line to outshine them, and Jimi told me that was one of the reasons he got fired - he was always doing tricks, stealing the show.

“You should always dare to be different,” Mayer asserts. “Copying and looking over your shoulder is no good. You should be looking forward, not backwards. A lot of white man’s blues today is just boring!

“Blues, by definition, cannot be learned; you can feel it, but there’s no way a white person can feel it in the same way as a black person who grew up with it in their neighbourhood.”

Kathy's song

Learn

The ultimate Jimi Hendrix lead guitar lesson

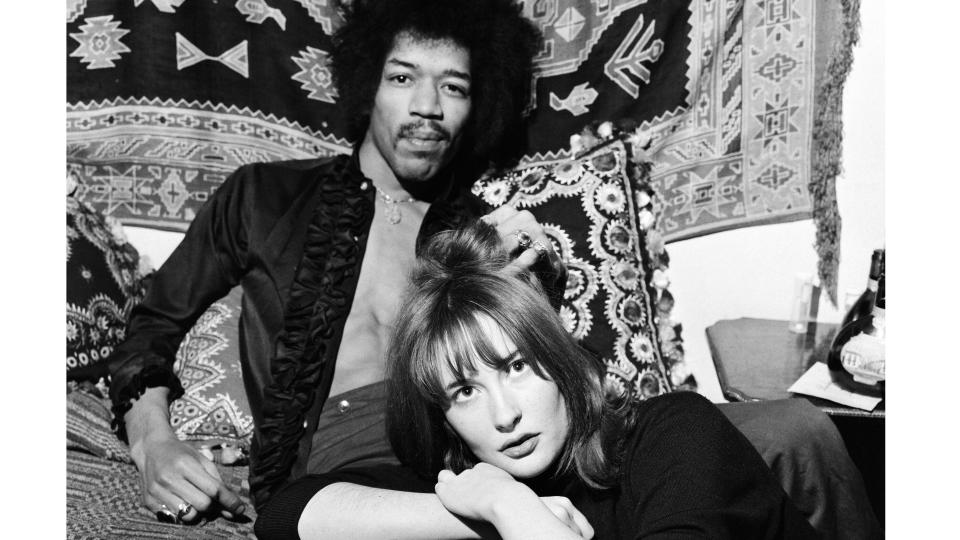

Probably no-one got to know Jimi Hendrix better than Kathy Etchingham, who met Jimi Hendrix soon after his arrival and was his girlfriend for three years. She remembers a man who wasn’t as supremely confident as his music might suggest:

“He had an enormous amount of confidence in his music, but, as an American in London, he was like a fish out of water. Chas Chandler thought, ‘Ah, we’ve got to get Jimi introduced onto the social scene,’ and that’s what he did. But in those early days we didn’t have any money, so we used to sit around a lot in the places we lived, planning out the future.

“We’d play games - card games, Monopoly, Scrabble - and, as time went on, we had more money and went out more often. Jimi certainly knew about English music before he came over, knew about Eric Clapton, admired John Mayall’s Blues Breakers and Cream.

When Jimi played with Cream... he walked offstage with this smirk; he knew exactly what he was doing

“Jeff Beck’s name would come up often; in my mind, I’m sure he preferred Jeff’s playing to Eric’s. There was real rivalry between Jimi and Eric. When they did talk, people might’ve thought it was all very friendly, but it was a stilted, difficult conversation where they tried to be nice.

“To be fair, it was difficult for Eric; he was the leader of the gang then this character comes in from nowhere. When Jimi played at the London Polytechnic with Cream, Eric strolled confidently off, then Jimi started playing Killing Floor and you could see the look on their faces. Jimi walked offstage with this smirk; he knew exactly what he was doing.

“When Jimi went back to the States to play at Monterey,” Etchingham concludes, “it was a big deal for him. Perhaps he didn’t have the confidence to realise how important he’d become in Britain. But, at the same time, I think he knew he’d worked his way up quietly, and knew in his heart of hearts he could blow them all away.”

A blues legacy

Read more

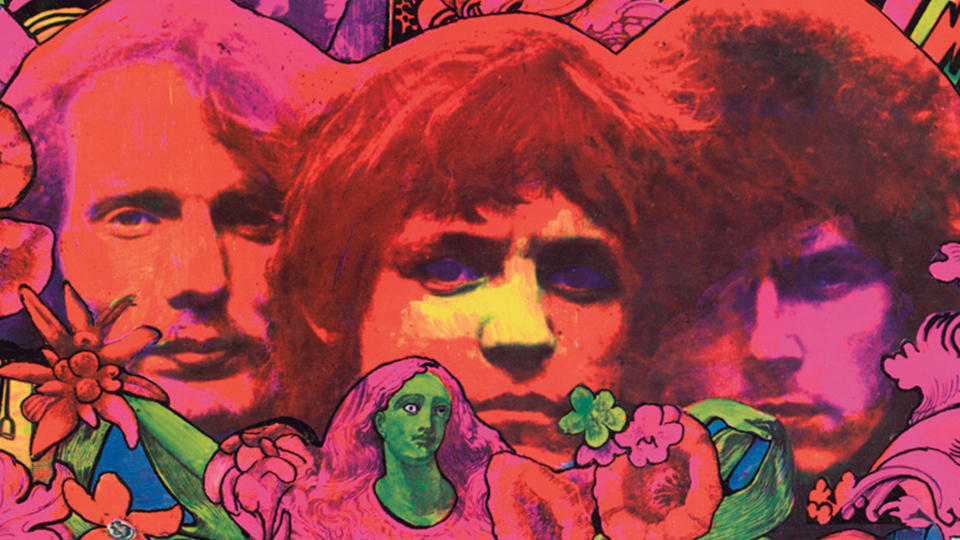

From those first appearances in the UK, Jimi took the world by storm, and in 1967 his first album, Are You Experienced, would stand alongside The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper and Cream’s Disraeli Gears as the great psychedelic masterpieces of the era.

In 1968, Cream disbanded, Eric Clapton later confessing: “My overall feeling is that it was a glorious mistake, and although it ended up being a wonderful thing, it was nothing like it was meant to be.

“But with Jimi, part of me wanted to run away and say, ‘Oh no - this is what I want to be,’ and part of me fell in love. But I just had to surrender and say, ‘This is fantastic.’”

The new live album, 'Jimi Hendrix Experience Los Angeles Forum: April 26, 1969' is out now on 2LP vinyl, CD and all digital platforms via Legacy Recordings (streaming links are here: https://hendrix.lnk.to/ForumPR). The new book, JIMI by Janie Hendrix and John McDermott is out 24th November.