West Side Story is not an old man's movie

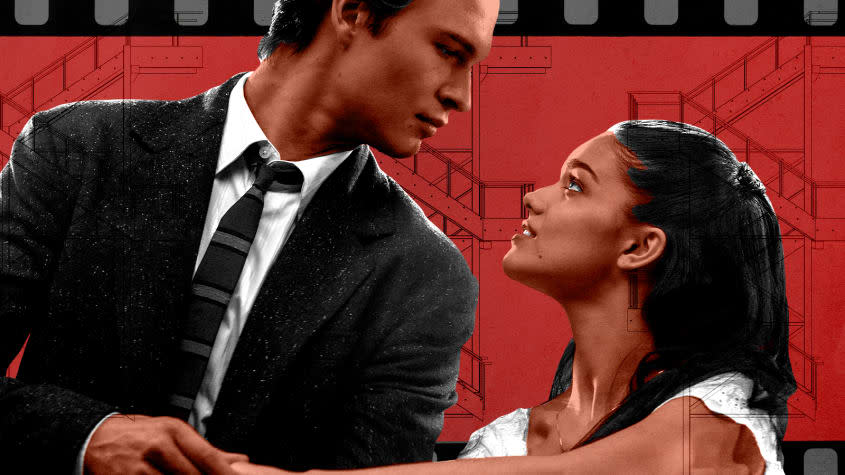

About a week after West Side Story is released in theaters nationwide on Friday, Steven Spielberg will celebrate his 75th birthday. Though he shot the film when he was "only" 72, there's nothing about Spielberg's musical that creaks like an old man's movie — beyond, perhaps, its origin as a remake of a classic stage show (and 1961 film) from half a century earlier. His camera whips around both sets and locations with boundless energy; this is the rare movie musical that feels as athletic and energized as the performers in it. It's not just a spirited run-through of classic material, either: Spielberg's new version of West Side Story, with an adaptation by Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright Tony Kushner, fine-tunes the material to more explicitly address racial tensions and gentrification without "updating" the text from its 1950s context.

West Side Story arrives just about 10 years after Spielberg's 2011 double feature, when he released The Adventures of Tintin and War Horse within days of each other. Technically, West Side Story kicks off a new decade; it's Spielberg's first film of the 2020s. At the risk of sounding morbid, this decade could also be his last; there aren't that many major directors who keep working well past 85.

Then again, much of Spielberg's career has been unprecedented, and his next project, reportedly a semi-autobiographical coming-of-age drama, is due out in fall 2022. In the meantime, it's worth examining his past decade of work — his most unpredictable period yet, and one that builds to culmination in his West Side Story.

Spielberg has long divided his time between making popular entertainments and stretching into more serious territory. This divide was clearly demarcated in the 1980s, when three of his seven films were Indiana Jones adventures; three were dramas like Empire of the Sun and The Color Purple; and one was E.T., which did a stint as the highest-grossing movie of all time. E.T.'s record was ultimately supplanted by Jurassic Park, a '90s sign that Spielberg's blockbusters could grow alongside the dramatic ambitions of movies like Schindler's List — and Saving Private Ryan later combined spectacle with dramatic intensity. In the 2000s, Spielberg pulled off a fascinating reversal: His big-budget sci-fi movies and thrillers like A.I. and War of the Worlds were surprisingly thorny, even alienating to some audiences, while smaller-scale projects like Catch Me If You Can and The Terminal were gently humanist — that is to say, they starred Tom Hanks.

Hanks has also figured into a number of Spielberg's recent films: He appears in the latter two of the filmmaker's loose civics-lesson trilogy of Lincoln (2012), Bridge of Spies (2015), and The Post (2017). Though seemingly old-fashioned, these movies comprise an ongoing experiment in fusing Spielberg's natural showmanship with stories that are, by design, talky and, on paper at least, potentially dry. All three concern negotiating labyrinthine systems, whether the imperfections of U.S. democracy or the ins and outs of Cold War spycraft and diplomacy.

Some of his other projects of the 2010s are more explicit technical exercises and experiments. The Adventures of Tintin (2011) is his only wholly animated film, shot using the motion-capture process that briefly enraptured his pal Robert Zemeckis, and The BFG (2016) hybridizes live-action and animation, with a motion-capture performance by Mark Rylance. And how to explain War Horse? It's a vignette-driven movie about a horse's adventures through different forms of European battlefields, part kid-friendly adventure and part war-is-hell parable, all executed with stunning skill. (It also arguably kicked off an increased interest in American movies about World War I, rather than the World War II narratives that have shaped so many of Spielberg's films.)

At first glance, Spielberg's recent run might appear muddled, as if he's wandering through dad-friendly American histories while occasionally trying to reclaim his mojo as an entertainer of children. But while his 2000s films have their many individual merits, West Side Story does a surprisingly credible job of tying Spielberg's past decade together. As a piece of filmmaking, it's as dazzling as anything he's ever made, a torrent of color, light, and shadow that all but erases the thin boundary between action sequence and musical number. Understanding how similar they really are, he harnesses the technical mastery of movies like Tintin and War Horse in service of a story that speaks to his interest in American history, here touching upon the immigrant experience and the changing face of mid-century New York City. Along with this year's In the Heights (Jon M. Chu), it's a potent reminder of just how expressive the movie musical can be — how song and dance can make some stories more vital and cinematic, rather than turning them into Broadway theme parks.

Spielberg still sometimes receives blame for that theme-park-ification of American cinema. His last movie, Ready Player One (2018), leaned into that reputation harder than anything since Jurassic Park, sending his young, bland hero through a virtual-reality pop-culture gauntlet, consisting in part of movies Spielberg directed or produced. That was supposed to be his hit of pure cinematic pleasure, but West Side Story manages to be both weightier and more kinetically exciting — another confirmation that Serious Spielberg and Showman Spielberg have become the same multifaceted filmmaker over the past decade. Now half a century into his filmmaking career, he doesn't need to be engineering theme-park rides to be firing on all cylinders.

You may also like

Serena Williams withdraws from Australian Open, citing medical team's advice

Kathy Griffin slams CNN for firing her but not Jeffrey Toobin

Chris Cuomo won't be paid severance after his firing, CNN says