“For me, Wish You Were Here is the most satisfying album. I really love it. I'd rather listen to that than Dark Side of the Moon”: David Gilmour opens up on the creative tension that built Pink Floyd's classic records

This interview with David Gilmour originally appeared in the February 1993 issue of Guitar World.

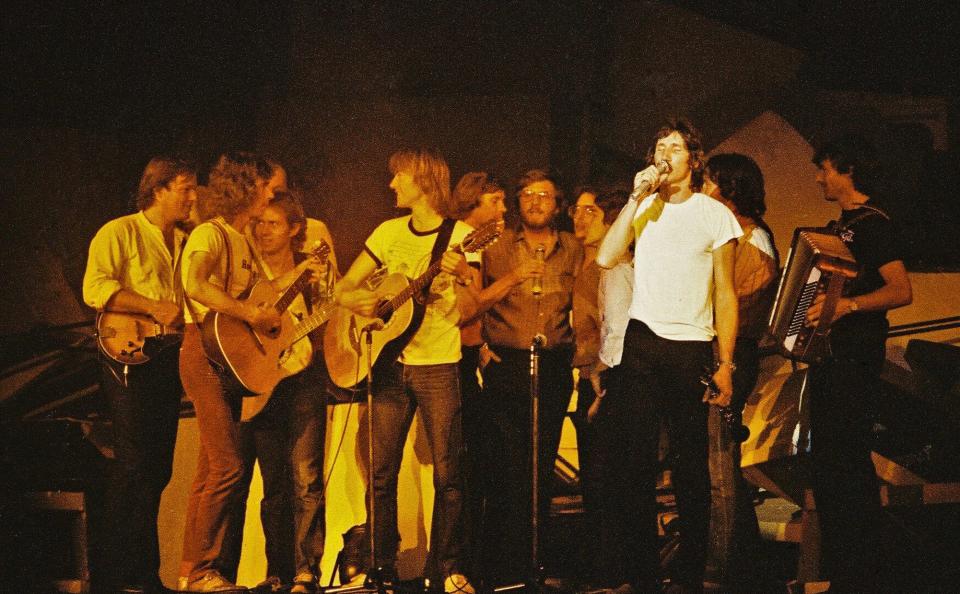

Amid the psychedelic explosion of new groups making their debut in the charmed world that was London, 1967, was a quartet called The Pink Floyd. In small, smoky clubs like UFO and the Roundhouse, the Floyd galvanized the London scene with their extended, free-form instrumental jams.

Fledgling flower children grooved to the heady new sounds in rooms that seemed to bob and levitate as blobs of multi-colored liquid light melted the walls around them.

Perhaps even more than Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Pink Floyd were psychedelia personified. By 1968, however, the band was forced to confront the rapidly deteriorating mental condition of Syd Barrett, their brilliant but unstable guitarist and leader.

In 1968, The Pink Floyd dropped the 'The' from their name – and they dropped Syd Barrett.

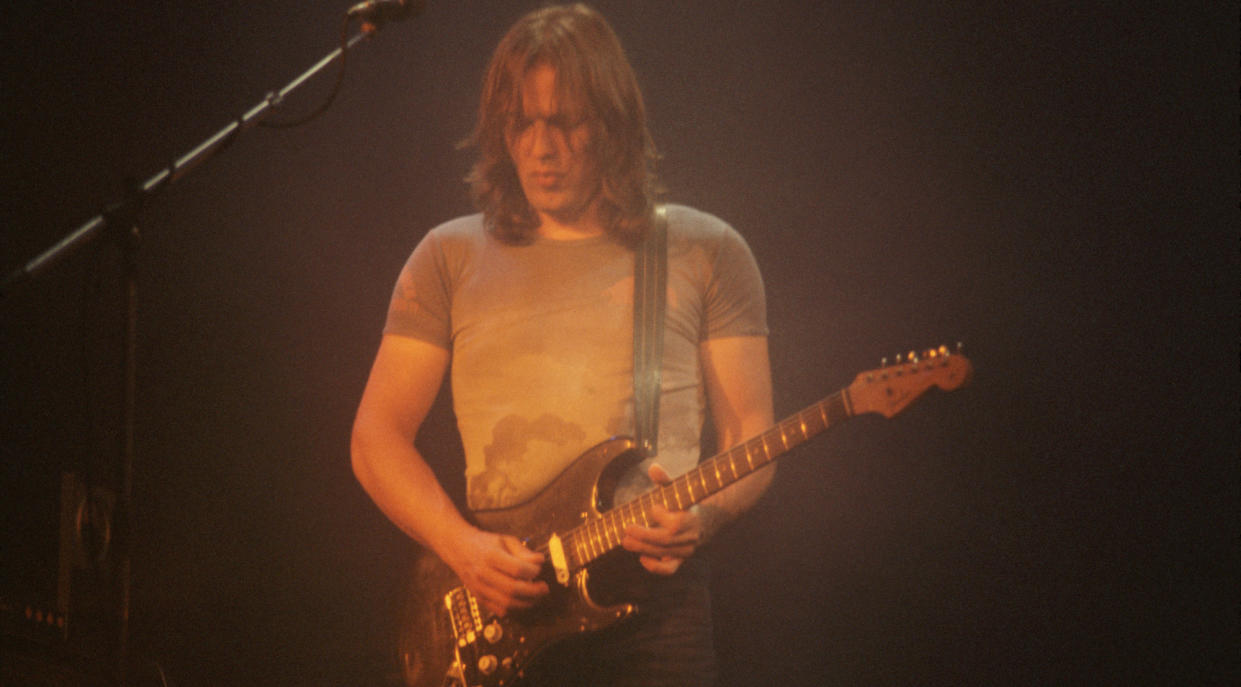

Guitarist David Gilmour, an old school friend of Barrett's, was drafted to replace him. Unquestionably, Barrett invented The Pink Floyd, and his troubled genius would later furnish the subject matter for some of the band's best songs. But it was David Gilmour and his lyrical guitar work that provided Pink Floyd with the sonic signature that helped carry them to international stardom in the Seventies, when the smoky clubs of their swinging London days gave way to vast arenas and stadiums.

The Floyd's ever-evolving trippy instrumental textures reached the highest levels of complexity, perfectly complementing their otherworldly concert visuals.

Pink Floyd's next big crack-up didn't occur until 1985, when David Gilmour and bassist Roger Waters came to a bitter parting of the ways. Gilmour assumed sole leadership of the band in 1987. With Waters' brooding lyrics out of the mix, Gilmour's searing, expansive guitar style – the core of the band's sound since their flower power days – assumed an even greater importance.

These days, David Gilmour is a distinguished, gray-haired English gentleman who becomes instantly youthful once he gets a guitar in his hands. In celebration of Shine On, the new Pink Floyd box set, Gilmour consented to share some of his memories with Guitar World.

There's a famous story about Syd Barrett being phased out of the band in 1968. You were all in a van, on your way to a gig in Southampton...

“Not in a van, no. In a Bentley.“

Right. And someone said, “Oh, let's just not pick up Syd tonight.“ Can you recall who said that?

“Probably Roger. Certainly not me – I was the new boy. I was in the back. Someone probably said, 'Shall we go and pick up Syd?' And Roger probably said [in conspiratorial tones] 'Oh no, let's not!' And off we went down to Southampton.“

I don't think the band really knew quite where they wanted to go after Syd's departure

In the early days of Pink Floyd, did you feel like you were just a Syd surrogate?

“Oh, I was – no question about it. They wanted me to play his parts and sing his songs. Nobody else wanted to sing them, and I got elected. That was my job as far as live shows were concerned, anyway.

“Me and Syd played only five gigs together in Pink Floyd. Or maybe four. Maybe Southampton was supposed to be the fifth one, I don't remember. While all this was happening, we were also trying to make the new album, A Saucerful of Secrets. But live, we didn't play the tracks from that, but virtually all Syd's stuff. Because there wasn't anything else to do. It was either that or back to Bo Diddley covers.“

What made the band decide to take on a lengthy, abstract instrumental like Saucerful?

“That's hard to say. I had just joined the group shortly before that. I don't think the band really knew quite where they wanted to go after Syd's departure.

“A Saucerful of Secrets was a very important track; it gave us our direction forward. If you take A Saucerful of Secrets, Atom Heart Mother and Echoes, all lead logically to Dark Side of the Moon.

“A Saucerful was inspired when Roger and Nick [Mason, Pink Floyd's drummer] began drawing weird shapes on a piece of paper. We then composed music based on the structure of the drawing. We tried to write the music around the peaks and valleys of the art. My role, I suppose, was to try and make it a bit more musical, and to help create a balance between formlessness and structure, disharmony and harmony.“

There are varying opinions as to whether or not Syd is on the Saucerful of Secrets track.

“No, he's not. That's totally false. He's on three or four other tracks on the album, including Remember a Day and Jugband Music [Barrett's sole composition on the Saucerful album]. He's also on a tiny bit of Set the Controls For the Heart of the Sun. I think I'm on Set the Controls as well.“

Can you recall any of the techniques you used to get unusual guitar tones back then?

“Well, on the middle section of A Saucerful of Secrets, most of the time the guitar was lying on the studio floor. You know how mic stands have three steel legs about a foot long? I unscrewed one of the legs and just whizzed one of those up and down the neck – not very subtly.

“Another technique, which came a bit later, involved taking a small piece of steel and rubbing it from side to side across the strings. You just move it and stop it in places that sound good. It's something like an EBow.“

How did you hit on the idea of playing slide guitar on the instrumental One of These Days?

“I guess I was never particularly confident in my ability as a pure guitar player, so I would try any trick in the book. I'd always liked lap steels, pedal steels and things like that. The one thing I don't do is regular slide guitar with the thingie on your finger. I've never had any interest in that.“

Where did the famous 7/4 time signature for Money originate?

“It's Roger's riff. Roger came in with the verses and lyrics to Money more or less completed. And we just made up middle sections, guitar solos and all that stuff. We also invented some new riffs – we created a 4/4 progression for the guitar solo and made the poor saxophone player play in 7/4. It was my idea to break down and become dry and empty for the second chorus of the solo.“

What was [producer/engineer] Chris Thomas' role on Dark Side of the Moon?

“Chris Thomas came in for the mixes, and his role was essentially to stop the arguments between me and Roger about how it should be mixed.

“I wanted Dark Side to be big and swampy and wet, with reverbs and things like that. And Roger was very keen on it being a very dry album. I think he was influenced a lot by John Lennon's first solo album [Plastic Ono Band], which was very dry. We argued so much that it was suggested we get a third opinion.

“We were going to leave Chris to mix it on his own, with Alan Parsons engineering. And of course on the first day I found out that Roger sneaked in there. So, the second day I sneaked in there. And from then on, we both sat right at Chris' shoulder, interfering. Luckily, Chris was more sympathetic to my point of view than he was to Roger's.“

There's creative tension and then there's outright hostility...

“There's creative tension and there's total egocentric megalomaniacal tension, if you like.“

Did the prospect of having to follow the huge success of Dark Side of the Moon create a lot of pressure on you during the sessions for Wish You Were Here?

“Yeah, that's what the album's about, I think as far as Roger's concerned anyway. It's about that feeling we were left with at the end of Dark Side – that feeling of 'What do you do when you've done everything?' But I think we got over that.

“For me, Wish You Were Here is the most satisfying album. I really love it. I mean, I'd rather listen to that than Dark Side of the Moon. Because I think we achieved a better balance of music and lyrics on Wish You Were Here. Dark Side went a bit too far the other way – too much into the importance of the lyrics. And sometimes the tunes – the vehicles for the lyrics – got neglected. To me, one of Roger's failings is that sometimes, in his effort to get the words across, he uses a less-than-perfect vehicle.“

I just had a different view of our relationship with our audience than Roger did

Throughout the Seventies and Eighties, each successive Pink Floyd album grew slightly more elaborate. Was it difficult to reflect that growth on stage?

“Actually, very difficult. We spent years gathering experts around us – just gaining the necessary expertise in all the areas we wanted to be good in. It was always a lot of work, but we looked forward to playing.“

Would you say you felt more at ease in the very early days of the band's free-form psychedelic experimentation on stage, or in the later period, when you relied more on carefully orchestrated stage extravaganzas?

“Somewhere in the middle, really. For me, The Wall show was terrific fun, and a great achievement. But I had to take on the role of music director, if you like, and deal with a lot of purely mechanical things onstage so that Roger didn't have to think about them. I had a huge cue sheet up on my amps, because we had all these cues coming up on monitors or on screen and different delay settings which I had to transmit with very primitive equipment to all the delay lines on stage. Very tricky.

“Once you got over being satisfied with how clever it was and how wonderfully it all worked, there were virtually no moments except for the solo in Comfortably Numb when you could say, 'Forget it, just blow. Just play.' Having said all that, though, I should add that I like structure. I'm very keen on melody, I'm a big Beatles fan, and just about everything else I love – like the blues – is highly structured. Totally free-forming is not my thing. But totally rigid structure isn't either.“

While the earlier Pink Floyd records were concept albums, The Wall is the first one with an outright plot. What were your feelings about that?

“I liked Roger's story line. Although I didn't totally agree with it, you've got to let a chap have his vision. I just had a different view of our relationship with our audience than Roger did. Roger didn't like touring. And he felt there was no connection between him and the audience that were in front of him.

“I had a different view of it – I still do. And my view of what The Wall itself is about is more jaundiced today than it was then. It appears now to be a catalog of people Roger blames for his own failings in life, a list of 'you fucked me up this way, you fucked me up that way'.“

What about your solo on Comfortably Numb? Did that take a long time to develop?

“No. I just went out into the studio and banged out five or six solos. From there I just followed my usual procedure, which is to listen back to each solo and mark out bar lines, noting which bits are good. In other words, I make a chart, putting ticks and crosses on different bars as I count through – two ticks if it's really good, one if it's good, and a cross if it's no go.

“Then I just follow the chart, whipping one fader up, then another fader, jumping from phrase to phrase and trying to make a really nice solo all the way through.“

How do you view your relationship to the guitar?

“It just happens to be the instrument I can best express my feelings on. I'm not very fast on it, but you don't have to be. You hear something like John Lee Hooker doing Dimples. Between the vocal lines he just hits the bottom string on the guitar – boom! – that one note says it all.“