The Yin-Yang of David Byrne: How the Unease of American Utopia Gave Him 'Reasons to Be Cheerful’

If the brain is a computer, then David Byrne’s runs on a binary code of two simple questions: “Why?” and “Why not?” It’s a system that has worked well for the supremely prolific artist once dubbed “Rock’s Renaissance Man” by TIME— a title that sounds lazy until you consider that “Musician, Composer, Author, Film Maker, Sculpture, Actor, Cycling Enthusiast, Oscar Winner, Budding Neuroscientist, Designer, Photographer, Global Music Curator, Talking Heads Founder and National Treasure” wouldn’t fit on a magazine cover.

“Why?” is a hallmark of Byrne’s best-loved songs, immortalized by his famous existentialist cry: How did I get here? His bemused observations about life slice through artifice, revealing the primal needs (See: More Songs About Buildings and Food) or absurdity (See: “Making Flippy Floppy”) unsettlingly close to the surface. The lines would seem cold if they weren’t so damn funny, and clinical if he didn’t include himself in the cosmic joke of being alive. But the surprising outcome of the 2016 U.S. presidential election made it clear to this avid student of human behavior that there was even more to contemplate. My God, what have we done?

This confusing time of national soul-searching sowed the seeds for Byrne’s latest album, American Utopia. With a sincerity and cautious optimism that fail to completely mask a deep malaise, he creates vivid impressionistic portraits of Trump’s America with the same dystopian flair he brought to Cold War paranoia on songs like “Life During Wartime.”

Overt protest songs aren’t really Byrne’s style. Instead, he depicts some of the less savory aspects of American culture with an eerie detachment that defies any form of argument. “Bullet” illustrates a murder from the impassive point of view of the projectile. “The bullet went into him / His skin did part in two / Skin that women had touched / The bullet passed on through.” The track “Gasoline and Dirty Sheets” explores consumerism from the perspective of a refugee, who is all too aware they aren’t welcome. “Vacuum-packed don’t rock my world / And the money back guarantee don’t make my day / No feeling of security/ They say the answer’s one click away.” The standout “Every Day Is a Miracle” overflows with classic Byrne one-liners: “A cockroach might eat Mona Lisa / The Pope don’t mean s— to a dog.”

Nominally a solo work — his first since 2004’s Grown Backward — the album finds Byrne working with a host of talent, including longtime collaborator Brian Eno. (He has since written an open letter expressing remorse for the lack of women on American Utopia’s credits.) Hanging over the proceedings is the fundamental question of “Why?” Why has this happened? Why did we choose this path? “These songs don’t describe an imaginary or possibly impossible place but rather attempt to depict the world we live in now,” he says in the album’s press release. “Many of us, I suspect, are not satisfied with that world — the world we have made for ourselves. We look around and we ask ourselves — well, does it have to be like this? Is there another way?”

That brings us to “Why not?”, which Byrne often manifests in rather whimsical ways. Why not start a record label to share obscure music from across the globe? Why not bring high school color guard teams to Barclays Center? Why not lead a crowd through a David Bowie song in the lobby of an upscale New York theater? Occasionally it presents as constructive criticism. This is the prevailing ethos behind “Reasons to Be Cheerful,” a lecture series in which Byrne shares positive innovations and campaigns collected throughout his international travels. By spreading these potentially scalable ideas, he hopes to jumpstart civic engagement in areas ranging from healthcare and climate change to transportation and education. In true Byrne fashion, it’s a very practical, clear-eyed attempt at trying to change the world.

American Utopia and “Reasons to Be Cheerful” are complementary opposites. Byrne mitigates the anxieties vented through the former with proposed solutions in the latter. Intriguing and enjoyable on their own, taken as a whole they are a compelling survival guide for an uncertain time. Together they are Byrne’s “Why?” and “Why not?” — a yin-yang for an exceptionally curious mind. The man himself elaborated during a recent conversation at his loft studio in downtown Manhattan.

Was American Utopia a direct offshoot of the “Reasons to be Cheerful” project or did they happen concurrently and inform each other?

Sort of concurrently, sort of in parallel. I didn’t conceive of them of having anything to do with one another. It wasn’t until later that I thought, “Well these things are kind of, in a way, talking to one another and reflecting off one another. Maybe the record is asking questions or describing the world as I find it and the other thing is saying, “But hey, there’s some good stuff out there! People are doing good things.” And I don’t mean rescuing a cat out of a tree or somebody donated liver — all of which is great stuff.

It’s definitely an interesting time to have an album with “American” in the title…

Yeah, I thought, “Okay, let’s put this out there and see what happens.” It makes for an interesting conversation. [laughs]

You’ve said this album is, indirectly, about “aspirational impulses.” Why do you think that in a developed nation we seem more miserable than most? Do humans just have a knack for getting in the way of their own happiness?

Wow, that’s a really good question. I think it’s definitely true that happiness and discontent are relative. You compare yourself to how other people are doing. So if lots of your peers are in the same boat as you, you kind of feel okay. But if you feel like, “Oh look, there’s this world of incredible wealth. Where am I here?” you start to feel envious or angry or whatever else relative to what you would like yourself to be. I can’t verify this myself but I’ve heard that a lot of times social media has a similar effect. Especially for kids — they’re comparing themselves to their contemporaries so they want to present themselves in the best possible light. If they feel like their life is not measuring up to the “Mean Girls'” life, they start to get unhappy and resentful.

So much of your art seems to come from point of view of an anthropologist trying to understand people. Do you feel like you’ve gotten any closer?

I feel like I’ve come a little closer but not that much. We’re still completely mysterious and baffling and surprising to me, which makes us interesting. But I’m definitely aware. At first I took offense at being called an “anthropologist from Mars”… [laughs]

I didn’t say from Mars!

You didn’t, but other people did! But then I thought, “Well, there’s a certain truth to that.” I don’t know about the Mars part, but there’s a certain truth to it. I’m often going, “Wait, why do we do that? Why do I do that?!”

You’ve worked with so many people over the course of your career, but Brian Eno is such a recurring figure. What makes your working relationship so fruitful?

I think it helps that we don’t consistently talk about music. We’ve stayed friends. We don’t communicate all the time, but often when we do we get together we might not talk about music at all. And then we might get around to music and sometimes we end up collaborating. But the last time I saw him a few weeks ago in London he was telling me about this organization that he was really fascinated with called Forensic Architecture. They technically reconstruct where something happened and how something happened. Using the phone videos and images, they can reconstruct the sequence of events. He was fascinated by that, and that’s not really talking about music.

For your last collaboration [2008’s Everything That Happens Will Happen Today] you had a clear division of labor— he did music and you did the lyrics. Was that the case for your songs you wrote together on this album?

On this album, it got more mixed up. Brian passed me a bunch of drum programs that he had done that I really liked and I had some words so I wrote words and melodies on top of these. He added some more instruments, but then more people came on board who added more and more and more and more and it kept evolving and kept changing. So rather than it being kind of a simple delineation of our previous collaboration where I wrote words and vocal melody and he did pretty much all the music, on this one it evolved in different way.

Are there any tracks on the album that are particularly meaningful to you?

There are certainly lines that are my favorites. There’s quite few in “Every Day Is a Miracle.” I’m not going to go there but there are a few that always get a laugh.

“The Pope…”

“The pope [don’t mean s— to a dog],” yes. [laughs] All true! There’s one in “A Dog’s Mind”: “A dog cannot imagine what it’s like to drive a car.” Which is, again, probably quite true. But there’s something profound about it, too. It’s funny and slightly absurd but to me it’s profound and it becomes very emotional. I get very moved by some of those lines. I can’t explain exactly why. I can get choked up singing those very lines. Go figure.

I imagine that achieving industry success makes it hard to maintain your creative freedom because there’s a certain amount of expectation, at least on yourself. How do you keep the pressure off and allow yourself to play creatively?

People do it in different ways. In some ways I kind of walked away from where I saw the success of Talking Heads going. As wonderful as it was, I felt that it was in some ways a little bit of a creative trap. So I walked away and said, “I don’t mind having a little less success, or a slightly smaller audience, if it allows me more freedom.” I can still make a living and do more of what I want to do, and sometimes fail and try different things. That, to me, is a better long-range prospect of a life. Not everyone wants to do that. Some people might feel, “No, take the success and work it as much as you can, and if you want to relax and indulge in your own thing, do that on your own time!” [laughs]

Can you tell me a little about the upcoming tour? You’ve compared it, loosely, to Stop Making Sense — at least in its level of ambition.

Our show is a very, very simple idea. I was inspired by the show I did with St. Vincent where we had all the brass players mobile; they could move around. So I thought, “Can we do this with everybody? How many players do we need in order to reproduce the sound of a drum kit, like a marching band or a drum line or something like that?” We figured it out so musically, we can do it. We have more people, but we can reproduce the sound. Then we had to figure out all of the technical issues, like wireless channels and transmitters and receivers and all this kind of stuff. But that meant we could have a completely empty stage and it becomes just about us — us as human beings moving about, interacting, reacting with the audience, all that. It’s a really simple idea but really challenging to execute. But it’s working, we’re in the middle of rehearsals.

We made a border out of a chain — a very fine chain, not a heavy chain. It’s about finding something that would not be affected by wind when we play outdoors shows like Coachella. If there’s any wind and you have scrims or drapes or anything like that, they’re going to all blow all over the place. So we said, “Is there any way around that?” So we have these very fine chains that look like a curtain but the wind goes right through it.

For “Reasons to Be Cheerful” the production felt very collaborative with the audience. Is that true with this tour?

Not [collaborative] with the audience, but there are definitely collaborative elements. The choreographer is a woman named Annie B. Parsons, whom I’ve worked with before in the past. Although she might be listed as a choreographer, it goes a little bit beyond that. It’s more about staging; it’s not just about the dance moves or anything like that. There’s a lighting director who will be asking us to do certain things that will work with the lights. Yeah, it’s very collaborative.

Dancing and movement plays such a huge role in your art. You even have a song on the new album, “I Dance Like This.” I myself am unable to access that part of my soul. So for a PSA for people like me, how do you get to that state of release?

I think to some extent I got to a point where I just didn’t care. [laughs] I didn’t care what people thought about my dancing. I’ve realized that sometimes I looked like the nerdiest white guy trying to dance and I just had to accept that was what I was doing. And it worked — it worked! People accepted it, and people actually got to like it! I realized, “Oh, I can find a way to move that comes from me and is not me trying to be some slick professional dancer,” or something like that.

Just purely from the spirit.

I hope so.

I saw the video you made with Choir Choir Choir group recently. How did you come to lead a couple hundred people through a David Bowie song in a New York City theater lobby?

Oh, that was fun! I’d done a couple sing-alongs — Brian Eno has a little singing group, I did one at Town Hall where I led everyone through a Whitney Houston song and that was a lot of fun — but I’d seen the Choir Choir Choir guys online and I thought, “These guys really know what they’re doing. How do they do this?” It’s kind of a choir of complete amateurs and they teach them real parts. They teach them structure and harmony parts — “Okay, you come in here and you come in here, and you do this and you do that.” I saw a couple online and I thought, “This is really amazing. I’d love to do this if I ever get in touch with them.” Well, they reached out because they were going to be here for this Under the Radar theater festival. As soon as they asked I said, “Yes, let’s figure out which song to do.”

You wrote a diary entry after the fact: “We cling to our individuality, but we experience true ecstasy when we give it up.” I thought that was a very interesting sentiment coming from someone so fiercely individual.

Yeah, that’s a contradiction in life, but you really experience it in those kind of events. It was really an amazing feeling, and the audience senses it, too. As I said, this is not about taking a solo or expressing your personal interpretation of the song. In order to participate it’s about fitting in with everybody else. And when everybody does that, it kind of lifts up and everybody has this ecstatic experience.

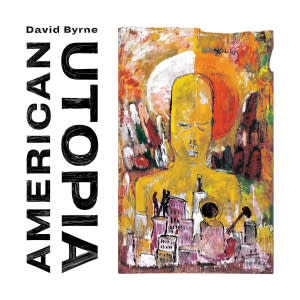

I’m hard-pressed to think of anyone who’s done more to make inclusive art, from stuff like Choir Choir Choir to Playing the Building, Contemporary Color and the bike racks you designed. It even extends to your album cover — how did you choose that painting?

We were at the stage when it was time to come up with a record cover. [laughs] I was watching a documentary, I think it was a French documentary, about a number of outsider artists. I was familiar with some of them but I was really enjoying it. As I was watching it I was realizing that with a lot of these artists, their artwork reflects what they imagine to be a be a better world. This guy, [points to a painting on the wall of his studio] Howard Finster, paints these imaginary cities — some of which he thinks might be the future. Not everybody is so utopian, but some are. I’ve realized that quite a few do that. This guy, Purvis Young in Miami, is doing it in a very human way. He painted these benign figures that seem to be blessing humanity in some way, encouraging people to be their better selves, and then he’d have other paintings of hundreds of people dancing. I thought, “That’s the same thing. He’s trying to imagine a better world and express it in his work.” I stumbled on the one picture, or one very much like it, which ended up on the record cover. I thought, “Okay, this might be kind of a visual expression of what the idea of the record is.”

Do you consider yourself an optimist?

Some of the time, although I really have to work at it. Hence the “Reasons to Be Cheerful” project. It’s a struggle, I have to convince myself. It’s really much easier to be cynical or critical and to think that everything is going to hell in a handbasket. But I’m trying.

Well here’s a positive note to end on: Friends of mine were married recently and they used one of your songs, “This Must Be the Place (Na?ve Melody),” as their first dance. Stripping away cultural commentary and all of the big points, what is it like knowing that your songs are held in a really personal, sentimental place for many people?

It’s obviously very, very flattering. To me it confirms what I felt when I was writing the song. I thought, “It’s really, really difficult to write a sincere, authentic love song that says it in a slightly new way, because it’s been said an awful lot of times in an awful lot of ways.” I resisted writing any overt love songs until then and I thought, “Can I do this? Is this going to hold up as something that feels like it’s true and isn’t just a bunch of clichés all strung together?” And I think it did. It worked for me, and to me, I think that [story] confirms that other people were feeling the same way.