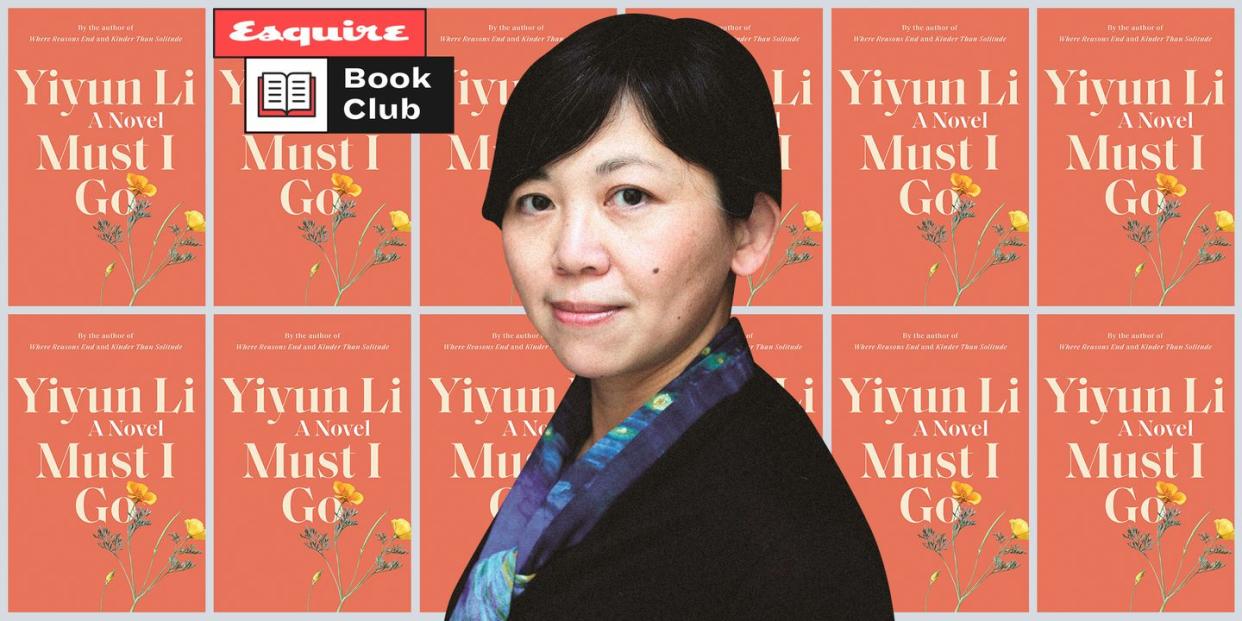

Yiyun Li Is Expanding Our Vocabulary For Grief

“Happy people have no use for words,” writes Lilia Liska, the proud and prickly 88-year old protagonist of contemporary master Yiyun Li’s latest novel, Must I Go. What does it mean, then, that Lilia has so very much to say?

In Must I Go, Li captures a difficult woman nearing the end of her days. At age 88, after three husbands, five children, and seventeen grandchildren, Lilia looks back on her uncompromising life from the numbing stasis of a nursing home, where she fills her hours annotating the newly published diaries of Roland Bouley, a deceased writer with whom she once had a fleeting affair. Though Lilia was merely a footnote in Roland’s life, she wars with his recollection of events, speculating about his two great loves while shading in the brutal details of her own long-buried personal history. She returns unendingly to the memory of her daughter Lucy, who took her own life at 27, and to the bottomless grief of losing a child to suicide. “Every morning since Lucy’s death, I wake up and say to myself: Here’s another day that Lucy refused to live,” Lilia writes. “Not a day she gave up. All the more reason for me to live each day, to prove a point: I refuse to accept her refusal.”

Li is a master of going to the places where words fail us. In her four novels and two collections of short stories, Li, one of our foremost writers of contemporary fiction, has plunged headfirst into grief, suicide, heartbreak, and countless other vagaries of the human heart. Yet Li’s talent is so much bigger than finding new depths to familiar pain. Perhaps her greatest talent lies in her peerless experimentation with our language of human emotion—its insufficiencies, its dissatisfactions, its refusal to capture the depth and breadth of our feelings. Must I Go is another remarkable entry in Li’s decades-long tug-of-war with the English language, which, luckily for her devoted readers, shows no signs of abating anytime soon. Esquire spoke with Li about wrestling with her complicated protagonist, immersing herself in the diaries of writers, and unlearning our tired vocabulary of grief.

ESQ: Where did Must I Go begin for you?

YL: The writing of a novel can sometimes become a novel itself. I like to read people's diaries and letters. If you read someone's diary and they mention someone, then you trace that person, it's like a chain reaction. At some point, I read a diary entry that said, “If there's a child born to a mistress, I would not have known it.” That line stayed with me, because any time a man says, “Maybe there's a child born somewhere not known to me,” a novelist's intuition is, “There must be a child somewhere.” That was the very beginning of this novel: a man saying, “Maybe there's a child somewhere.”

I didn't quite know who this man was. I kept a diary for him for about two months to get his voice in my head, so I started to write the novel from Roland's diary, and very soon, it became clear that it was not Roland's story, but Lilia's. From there, I moved to writing about Lilia. I had more than half of the draft done already when my son committed suicide. Lilia was 44 years old when her daughter Lucy committed suicide, and I was 44, too. I was so struck by this coincidence, and for a moment, I thought maybe I wouldn't finish the novel, because it was just too striking. I stopped there and wrote Where Reasons End, but I couldn't forget Lilia. She’s so different from me, but she’s always on my case. She's always talking to me. I came back to Must I Go again, this time with more understanding of Lilia's feelings about Lucy. It took me another year to finish the novel.

ESQ: Lilia is such a fascinating, prickly, difficult character. How did she change or develop throughout the writing process? Did she ever surprise you?

YL: She surprised me all the time. Sometimes I would go back to read the draft and think, “Did I write that?” She was so prickly, so funny, and so annoying, at times. Even after I finished the entire draft, she was still quite stubborn. She was so willful that it felt like I was battling with her. A couple early readers commented that she always had armor on. I started to think about that: where is her vulnerability? The revision was really a tug of war, with me pushing her to acknowledge certain pain that she would not admit even to herself. Eventually, there were moments where she started to open up, admitting that she didn’t cry over Lucy and that she lived by pride. That was as much as Lilia would admit me to her well-protected inner world, and that's when I felt I got to know her better.

ESQ: Every so often, we come close to Lilia revealing something of herself, only to back away from the cliff of real feeling and disappear into one of Roland’s diary entries. What was that like, writing a protagonist who can be very withholding?

YL: Frustrating. There were moments she would say something real and then tell a joke. Roland, of course, wrote with the intention to be remembered—not as Roland, but as someone much bigger than Roland. She'd run to hide in Roland's diary when she didn’t want to express her feelings. In my earlier drafts, she told more jokes. Sometimes I had to say “shut up,” because she could just go on and on telling jokes and making things frivolous, but her life is not frivolous. Her feelings are not frivolous. I wrestled with her.

ESQ: You say that Roland wrote himself as someone bigger than Roland. That calls to mind a line where Lilia writes, “Roland admits that he sometimes lies in his diary. Changes the sequence of events. Exaggerates.” What's at work behind this impulse to lie in a diary, a place intended for one’s truest, most private feelings?

YL: Over the years, I've read so many diaries, and you can see that some were not intended to be published; those were the true, private spaces where they talked with themselves. But there is the second group of diaries, where while they were recording their lives, they had a sense that posterity would read them. For instance, Katherine Mansfield would sometimes pause in her thoughts and address the readers. She would say, “To whomever you are, reading this right now, don't think you know me.” In that very direct, accusative tone, saying, “I know you're going to read this.” Even writers of the most true, faithful diaries still think about who will be reading them. The moment one thinks about people reading, especially in diaries, there's fiction going on, or at least the selection of certain details to tell a story.

ESQ: That makes me think of a gorgeous line from the book: “When you start writing about yourself, it feels like you could go on living forever.”

YL: Isn’t it true that sometimes, when we write, we feel life is fuller?

ESQ: Absolutely. But what’s the line between creating something true and authentic, versus creating something while thinking, “Who’s going to discover this? What are they going to think?”

YL: I think that even in our diaries, even if we are thinking or writing for ourselves, there's still a certain distance between we who write and we who read those words. There's always a sort of presentation going on. I wouldn't call it a performance, but there is a certain moment of presenting ourselves to ourselves. I think we write not to report facts, but to record our thoughts and feelings—to be understood and seen.

ESQ: So much of this novel takes place in the American West, while grappling with our mythology about settlers and pioneers. At one point, you write, “Pioneers are men, but pioneering is a woman's job.” What was resonant for you about that particular juncture of American culture?

YL: I think it had something to do with living on the west coast for a certain number of years. After awhile, you start to get to know the place. You start to read about the history of the place. When I lived in California, I was struck by how people talk about the east. They say, “back in the east,” and in that language, there’s a feeling that we actually came from the east—that's where home is, and this is the frontier. I think that language probably is passed down from generations of settlers. When I lived in California, we lived in the Bay Area. We now think of that place as Silicon Valley, but long before that happened, there was this gold rush and these settlers. California had this rich history. My other fascination when I wrote Must I Go was the 1945 UN Peace Conference. If you read the documents or you see the movies from the time, they used such hopeful language about the “golden future of humankind.” You stand next to the Pacific. You look east and you look west. I don't know if it's real hope, but there’s a hope that comes with California that fascinates me. The idea of settlers making this land a golden land.

ESQ: Lilia writes, “You can live a long life surrounded by people, but you'll be darn lucky if one or two of them can take you as you are, not as who you are to them.” Do you feel that we reduce people to the roles to which we assign them? Are we willfully blind to who someone is beyond the appellation of wife, husband, child?

YL: I've always been thinking about this. I agree with Lilia there. Not many people in our lives will take us for who we are, mostly because we are in human relationships, and those relationships have set terms—husband and wife, parent and child. For instance, I always think one of the biggest tragedies in life is that a child and a parent cannot be best friends—not in the way we are to our best friends. I feel there's a limit to any relationship that comes with set terms. Lilia has been thinking something that I've always been thinking about, too. Who will take us for who we really, truly are?

ESQ: It makes me think of the moment where she writes about putting her various husbands in drawers. How can anyone take you for who you are if you, in kind, are compartmentalizing them?

YL: See, those are the moments where I almost want to bonk Lilia on the head.

ESQ: It was so satisfying at the end of the novel when another woman at the retirement home chastised her.

YL: The woman says, “You're not often nice,” and she says, “I know. I don't want to be nice.” She's a fascinating woman. She's probably not the nicest friend.

ESQ: But I so appreciate that about this novel—how you resist those tiresome ideas of likability and relatability.

YL: I feel that's the fun of writing. We don't have to have the obligation to make up nice things. We might make up real things.

ESQ: Lilia spends a lot of time wrestling memories of those who've passed. Roland writes, “Rightly remembered, everyone is a curio decorating someone's mental mantle.” In your own experience of life and loss, how do you go about the project of rightly remembering loved ones who are no longer with you?

YL: In my life, when I look at the people I’ve lost, my biggest worry is that memory would make them better. Memory would make them less real and more optimized or beautified. I fear that I’ll remember someone not as they were, but as I wanted them to be. I think a tension exists between what's real and what you prefer to remember. I myself would prefer what's real.

ESQ: Lilia criticizes the way Roland remembers people, writing, “Roland didn't forget her, or else he wouldn't have kept the entries about her, but he remembered her. He kept her in the diaries because she made him look like an interesting young man. She was an interesting woman. This he forgot.” So often, we speak about writing about the dead as a way of honoring or remembering them, but what's the line between honoring the dead and exploiting them, as Roland seems to have done?

YL: For Roland, that’s certainly the case. He's really just using these people. Coming back to your earlier question, it’s like Lilia said: “Not many people take us for who we are, but who we are to them.” I think it's the same. If we honor someone, we're talking about who this person was in life, but if we honor someone to serve ourselves, then we’re just using that aspect of who this person is to ourselves. It's a matter of taking someone for who he is. It sounds easy, but actually, it’s not.

ESQ: On that same theme of loss, Lilia writes, “When Lucy died, the women in my life—my sister Margot, my in-laws, friends, and neighbors—they all tried hard to say the right things, but the right things are often the least helpful.” In what ways is our language about grief insufficient? What, in your experience, is the most helpful thing to say or do?

YL: I’ve been thinking about how people talk to those who are grieving. Our language of grief is so limited; we often don't acknowledge that. We always say “words fall short,” or “words are not sufficient to express”—which is exactly true. In Lilia's case, the women saying those things to her are saying them in part for themselves, to make themselves feel a little less grief, and that is often the case when people deal with grief. When I think about my friends who have experienced loss in the past few years, I realize that I don’t have the right words to say to them. I think the only thing to do is acknowledge that I can't find the right words, but I want them to know I'm aware of the situation. It’s so hard.

ESQ: This makes me think of the part of the novel where Lilia dissects the phrase “my heart is broken,” which she finds unsatisfying and untruthful.

YL: I've been thinking about that phrase, “my heart is broken.” I think there are certain words we use because we don't know what to do. We take those cliches from life and use them to express our feelings. But there must be a moment when the language was first created, when cliche was not cliche. The first person who said “my heart is broken”—it must have been so compelling, that expression. I think over the years, we're just accumulating these words, and writing, to me, is a way to look for new words to say these things.

You Might Also Like