100 objects that make Milwaukee

Some of us used to say we were from Milwaukee with a hint of shame.

But there are signs everywhere we look that Cream City is rising. Businesses are relocating here. Top Chef launched its latest season in the city, complete with footage of the Milwaukee Public Market, the Milwaukee Art Museum, the Hoan Bridge and other landmarks. And while Democrats and Republicans can’t agree on much these days, they both decided to hold their conventions in Milwaukee in recent years – or at least try to.

We wanted to celebrate our great city by honoring some of the things we love about it. The trouble is, there’s so much to love about Milwaukee that it was tough to decide which objects to highlight. (We settled on 100 objects; a push to do 414 was quickly shot down by editors.)

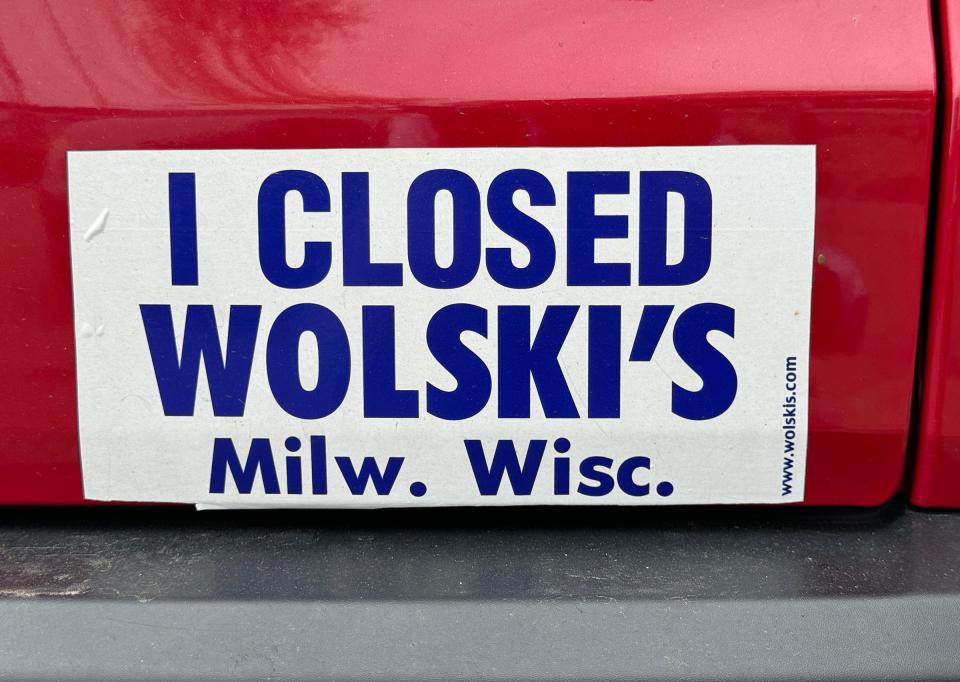

Some of the objects are stunningly beautiful, like the art museum’s wings and the Basilica of St. Josaphat dome. Others are delicious – like a Sobelman’s Bloody Mary, frozen custard and cheese curds. More than a few involve beer and sports, because of course they do. And we included some things that are just so Milwaukee – like racing sausages, Kohl’s Cash and “I Closed Wolski’s” stickers.

We also know Milwaukee isn’t perfect and has long faced deep problems like racism, segregation and inequality. So we also wanted to focus on the struggle for a better future by including key locations in the city, such as the 16th Street Viaduct, in an effort to honor the fair housing marches of the 1960s.

Next time somebody starts trashing Milwaukee, please tell them the city’s brightest days are still ahead. And maybe send them this list of 100 objects as a reminder that Milwaukee is indeed “the good land” full of promise – and some pretty great things.

—Mary Spicuzza

100 objects that make Milwaukee

Architecture

Culture

Entertainment

Environment

Food & drink

History

Sports

How did we come up with these 100 objects? Here's an explanation.

What did we miss? What doesn’t belong? Let us know here: bit.ly/MKE100More.

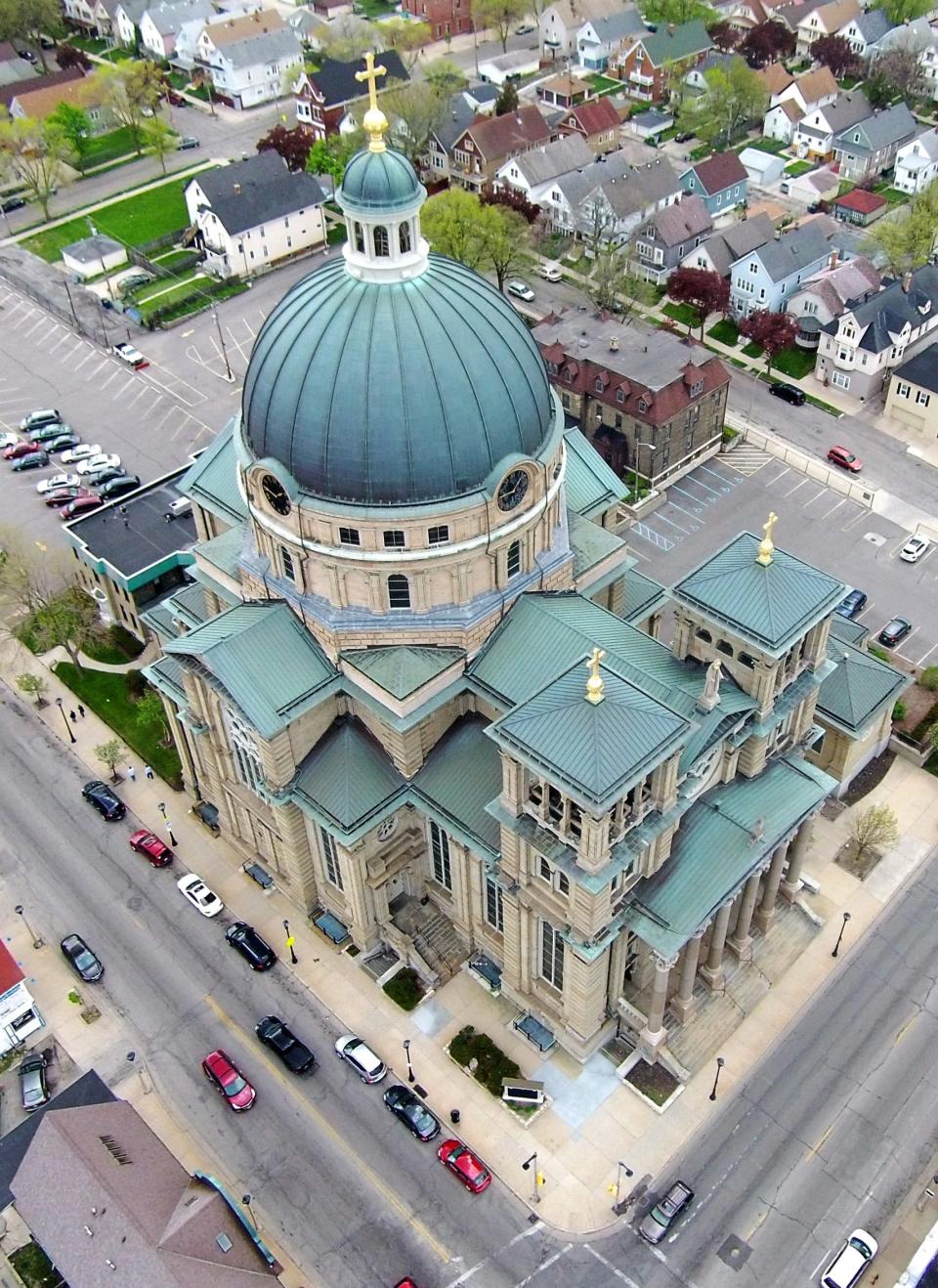

Basilica of St. Josaphat

The Polish immigrants who poured into Milwaukee in the late 19th century wanted a beautiful church that telegraphed their strong Catholic faith and ethnic heritage. And they were willing to do anything for it.

They mortgaged their homes to raise money. They volunteered their labor. Fr. Wilhelm Grutza, the blacksmith-turned-pastor, shipped 500 rail cars of salvaged materials from a shuttered Chicago post office. He died five weeks after the church's dedication in 1901, exhausted from overwork.

In a city dotted with steeples and infused with Catholic tradition, the Basilica of St. Josaphat stood out. Modeled after St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome, its 220-foot-high copper dome was only second in size to the U.S. Capitol at the time.

Today, 123 years later, the ornate basilica is still larger-than-life. It’s a tourist destination as well as a hallowed space. The faithful who gather understand they’re among tens of thousands who have knelt in the pews for prayer, and heard the acoustics echo, and craned their necks to take in the intricately decorated cupola.

It’s Milwaukee’s largest church. It’s always been an anchor of the south side. But its dome – first illuminated at night in 2019 – cemented the basilica’s place in Milwaukee’s skyline for years to come.

Even as church attendance and religious belief decline, the dome is a reminder of Catholics’ indelible impact on the city.

It calls to drivers passing on Interstate 43: I’ve been here over a century, and I’m here to stay.

-Sophie Carson

The Calling

Milwaukee has a contentious history with public art (Google “Blue Shirt” if you need a reminder). Ensconced in O’Donnell Park at the lakefront, Mark di Suvero’s steel-beam sculpture “The Calling” has survived several rounds of controversy with the staying power of the sun that it abstractly mimics.

Funded by an anonymous donor, it is made of steel I-beams painted orange and stands 40 feet tall. After 11 argumentative public hearings and much political grandstanding, the Common Council approved the artwork, which was dedicated in April 1982.

“Di Suvero certainly was aware that many people would see his work from great distances and from the windows of rushing cars, buses and trucks,” Milwaukee Sentinel art critic Dean Jensen wrote in 1982. “Through its great size, its garish color and the grammar of its simple forms, it asserts its essence quickly and directly.”

“The Calling” enjoyed a bonus kerfuffle in 2001 when architect Santiago Calatrava’s gleaming white addition to the Milwaukee Art Museum opened. Killjoys wanted the di Suvero away from the Calatrava sightline. The artist responded bluntly: “If you don’t want it, take it apart and ship it to me.”

As for the architect, he told Journal critic Whitney Gould that he designed the MAM addition with “The Calling” in mind. And if you stand along Wisconsin Avenue in the right spots, you’ll see that “The Calling” and the Calatrava addition line up perfectly.

-Jim Higgins

Harley-Davidson motorcycle

You know that sound. It’s the sound of spring, when warmer weather finally thaws the winter roads. It’s the sound of the wind blowing across your face and through your hair. It’s the sound of speed, freedom, the open road. It’s the sound of summer, long rides cross-country or a short trip to the beach.

It’s the sound of friends William Harley and Arthur Davidson’s turn-of-the-20th-century ingenuity that grew from tinkering in a backyard shed to the construction of a two-wheeled, motor-powered bike and the desire to make it go fast, then faster. It’s the sound of a business born in 1903 and raised in Milwaukee, then taking off to become an internationally known brand. It’s the sound linked to leather, and the smell of gasoline. It’s the sound of putting the pedal to the metal.

You know that sound. It’s the sound of a Harley.

-Jessica Van Egeren

Juneteenth Day Flag

June 19, 1865, is the most crucial day in African American history. On that day, federal troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, and declared that the Civil War was over and all 250,000 enslaved people in the state — the last remaining slaves in the South — were now free, more than two years after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation.

In 1997, a flag was designed to commemorate Juneteenth and was later revised.

The flag features red, white, and blue colors — from the American flag — with a white bursting star of freedom in the middle. An arc runs through the flag’s center to symbolize the new horizon of opportunity for African Americans. The blue is above the red because the red represents the ground soaked with blood from all those who came before us and fought for freedom.

Milwaukee’s annual Juneteenth celebration is one of the country’s oldest — the city was one of the first in the northern states to began officially celebrating Juneteenth, in 1971.

Juneteenth and its flag are significant for me as an African American. My grandparents, who lived in Mississippi, referred to it as “Jubilee Day,” and they celebrated it by enjoying strawberry soda and red velvet cake that symbolized the blood shed by enslaved West African ancestors.

This flag should be flown on Juneteenth and every day in our country.

-James E. Causey

Oak Leaf Trail sign

If you live anywhere in the Milwaukee area, you’ve almost definitely seen an Oak Leaf Trail sign. The over 135-mile multi-use trail traverses throughout Milwaukee County and is beloved by cyclists, runners, walkers, birders, skateboarders, rollerbladers and more. It’s a mainstay in numerous local running races throughout the year.

The Oak Leaf can take you pretty much anywhere in Milwaukee and offers beautiful views; nearly a quarter travels along the Lake Michigan shoreline. The trail’s nine branch lines connect users to dozens of county parks, beer gardens and attractions in the area.

The Oak Leaf also intersects with various other municipal trails, allowing for travel beyond the county. The northern terminus connects to the Ozaukee Interurban Trail, which users can take all the way to Sheboygan County.

While it’s hard to imagine the Oak Leaf without its variety of users today, it was not open for non-cycling use (or given its current name) until 1996. The trail’s origins date back to the late 1930s, when local cycling enthusiasts established an about-65-mile bike route around Milwaukee County.

Three decades later, the trail was officially recognized by the county parks department. In 1976, it was christened the “76 Bike Trail” in honor of the national bicentennial.

-Claire Reid

Beer garden stein

For more than 150 years, few objects have represented the city of Milwaukee better than a mug of beer – the key component of gemütlichkeit, which Milwaukeeans have pursued since long before prohibition.

Beer steins clutched in the hands of dozens of strangers crowded together at long wooden tables under tree canopies represents the city’s long devotion to the craft of beer brewing and community, and pays tribute to the city’s sturdy Germanic roots.

German immigrants inspired the creation of the city’s breweries and made beer gardens the quintessential gathering spot of Milwaukee. According to the Milwaukee County Parks Department, more than two dozen breweries were in operation by 1856, making way for beer gardens along the Milwaukee River.

Prohibition in the 1920s curtailed such gatherings, but the idea has experienced a revival in recent years.

The city has several permanent beer gardens, including the popular Estabrook Beer Garden along the river greenway in the city’s northeast side, between Shorewood and Whitefish Bay. And the county’s Traveling Beer Garden tours bring the beer garden experience to neighborhood parks around the city throughout the summer.

Here, you can fill your beer stein with Hofbrau, wash down bratwurst or a soft pretzel, and watch your neighbors polka – just like Milwaukeeans did generations before.

-Molly Beck

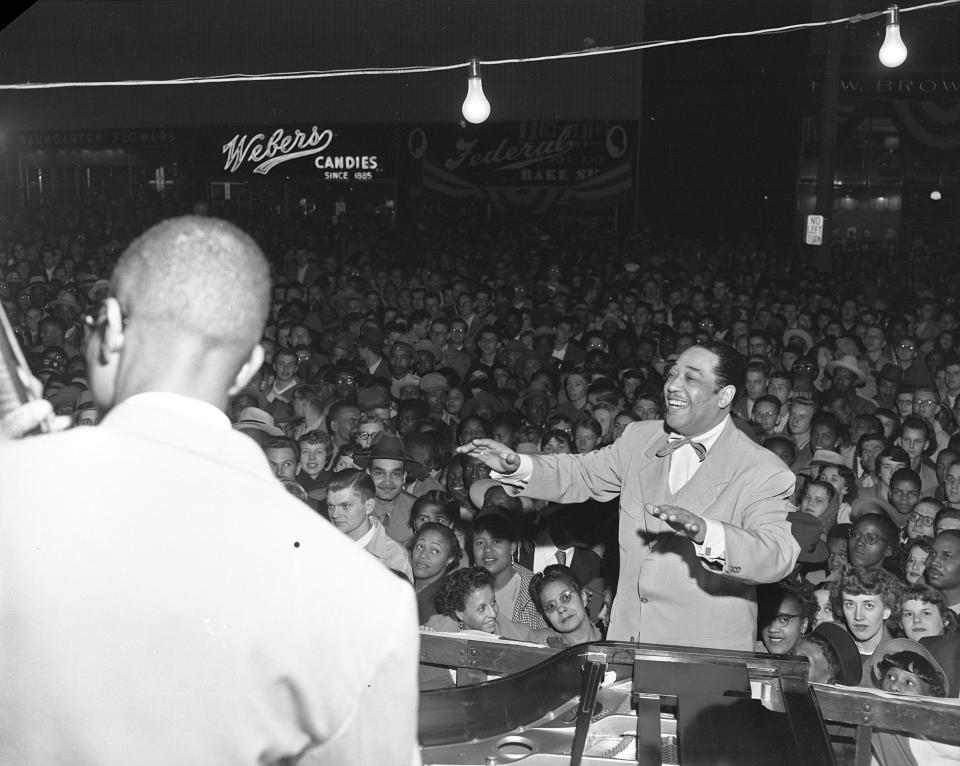

Washington Park Bandshell

Music can bring a community together.

Want proof? Just visit Washington Park’s bandshell on a Wednesday evening in the summer.

You’ll see families and friends spreading out blankets and popping open lawn chairs on the grassy amphitheater.

You’ll smell barbecue, wood-fired pizza and popcorn wafting from local vendors’ food trucks.

And depending on the night, you’ll hear classical, jazz, reggae, opera, folk, rock, punk or a fusion of genres.

The stunning art deco bandshell is formally known as the Emil Blatz Temple of Music, named for the man who came from a brewing dynasty and donated $100,000 for its construction in the city’s largest park.

At its dedication in 1938, a crowd of 40,000 – “a mass of mothers, fathers, maidens, swains and wide-eyed children” – heard a performance from the Wisconsin Symphony Orchestra and singer Jessica Dragonette, The Milwaukee Journal reported.

“If this temple of music gives you as much pleasure as it has given me in donating it, I am fully repaid,” Blatz told those who gathered on the lawn.

In the 86 years since, the bandshell has hosted musical legends like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Lily Pons, often as part of its “Music Under the Stars” program, which ran for 55 years.

Today, Washington Park Wednesdays, a free concert series, carries on the tradition, providing a welcoming space for neighbors of all ages to sing, dance and listen.

-Ashley Luthern

Burnham Block

When it comes to Frank Lloyd Wright, most Wisconsinites think of Taliesin, the architect’s home and workshop in Spring Green, the S.C. Johnson headquarters building in Racine or Monona Terrace in Madison.

But did you know there’s an entire block on the city’s south side that’s a showcase for Wright’s more modest designs?

The Burnham Block is a one-of-a-kind collection of six buildings constructed in 1916 as models for affordable housing for working-class people. The collection of single-family homes and duplexes on the 2700 block of West Burnham Street have the typical Wright touches of rich woodwork, tall vertical windows and natural construction materials, but they’re substantially smaller than the homes Wright had previously designed.

“These are Frank Lloyd Wright’s vision to house every person, every American in a beautiful, artistic place to call home,” said Mike Lilek, curator for Frank Lloyd Wright’s Burnham Block, Inc., the nonprofit that owns five of the six buildings.

The organization has restored two buildings, which now function as a museum that is open for public tours. Plans are being developed for restoring the home on the northwest corner of South Layton Boulevard and West Burnham Street.

You can make reservations for a guided tour at wrightinmilwaukee.org.

-Karl Ebert

Hoan Bridge

Greeting visitors by water from the east, the Hoan Bridge is both Milwaukee’s iconic and ironic symbol for the city’s socialist history.

Former Mayor Daniel Hoan, the city’s longest serving socialist mayor, had much of Milwaukee onboard with his policies, but when the bridge for part of Interstate 794 was erected in his honor, many were dismayed.

“Where transportation was concerned, Dan Hoan was no fan of car culture,” said Phil Rocco, associate professor of political science at Marquette University. “Quite the opposite. He often bitterly complained that cars locked the city into a dynamic of ever-greater spending on ever-widening streets and that greater traffic jeopardized public safety.”

The public gets an up close and personal view of the Hoan, which opened for traffic in 1977, during the highlight of Milwaukee’s warm months — Summerfest.

It crosses over the Milwaukee Harbor, welcoming shipping, and connects downtown to Bay View and other parts of southern Milwaukee County. It’s in the foreground of many photographers’ shots of the city skyline, and is lit every night, often to honor an event or person.

Coined the “bridge to nowhere” during construction, the Hoan has very much become part of Milwaukee’s image.

-Drake Bentley

Jake’s Deli pastrami sandwich

You don’t have to be the commissioner of Major League Baseball or owner of the Milwaukee Bucks to eat like them.

At Jake’s Delicatessen, 1634 W. North Ave., patrons can walk and eat in the shadow of former MLB Commissioner Allan H. “Bud” Selig and late Bucks owner Herb Kohl, who frequented the deli.

Jake’s Deli opened in 1955 and catered to the many Jewish families who had emigrated from Eastern Europe to the Haymarket and Sherman Park neighborhoods. In 1969, Selig bought an ownership stake in the business and held it until Wajeeh Alturkman bought it in 2021.

Jake’s has a modest appearance with a vertical street sign that reads “Jake’s.” Those in search of a good sandwich don’t need any further description.

Jake’s is known for its corned beef, but it’s the pastrami sandwich that gets people talking. Patrons have a choice to get the rye bread toasted or keep it plain, with yellow or brown mustard and their choice of cheese.

If they take a seat on the bench by the counter, the meat is cut slowly right in front of them. And a pickle spear is served on the side.

-Ricardo Torres

Giannis mural

Like its subject, downtown’s mural of Milwaukee Bucks superstar Giannis Antetokounmpo is larger than life — covering the three-story back wall of a historic office building at 600-606 E. Wisconsin Ave. It was painted there in spring 2022 by local artist Mauricio Ramirez. The building is owned by Dan Nelson Jr., a Bucks season ticket holder and president and chief executive officer of Nelson Schmidt Inc., a marketing communications agency that operates at the building.

For Giannis fans, it’s a must-stop photo op, and perhaps Milwaukee’s best-known mural.

His legacy is still being written, but already includes being named Most Valuable Player in the 2021 NBA championship series and two regular season MVP awards in 2019 and 2020. And it will always include Milwaukee, where we’ve watched him grow from a teenager to a dominant player, an involved father and a noted fan of chicken nuggets.

Bucks in six!

-Tom Daykin

Granny in the Streets of Old Milwaukee

How do you decide on an iconic symbol to symbolize a place that is so iconic?

I’m speaking of the Milwaukee Public Museum. And, if you’re in a roomful of Journal Sentinel reporters and editors, the answer is, not without a fight.

The museum has been around (in various iterations and locations) since 1851. And it’s become a go-to place for field trips and weekend excursions.

So this reporter (having been on many such field trips and excursions) suggested the rattlesnake button for MPM’s symbol. Because how could you possibly end a trip to the museum without sitting on the ledge surrounding the bison hunt exhibit, reaching your hand underneath and flicking the switch? The answer is, you cannot.

Another reporter proposed the T-Rex, which for decades has been famously munching on the remains of his fallen prey in the museum’s strikingly realistic (and scary) dinosaur diorama.

After vigorous debate, we were outvoted by proponents of Granny, who calmly rocks in her chair on the porch of her house in the Streets of Old Milwaukee. Granted, she does live in possibly the most popular exhibit ever at the museum. And (especially impressive for someone her age), she has her own social media accounts. So who is this reporter to argue?

But MPM apparently agrees the rattlesnake button and T-Rex are iconic since they’ll be making the trek to the new museum, slated to open in 2027. Granny will be there, too.

-Amy Schwabe

Samson the gorilla

Most will agree that a trip (or two or several) to the Milwaukee County Zoo is necessary if you want to call yourself a true Milwaukeean.

And many Milwaukee children (or grownups waxing nostalgic about their childhoods) will agree that a trip to the zoo is not complete without a ride on the train and a Mold-a-Rama souvenir of their favorite animal. This is universal.

Less universal is choosing your favorite zoo animal. Milwaukee has had some famous ones over the years, from Gordy the groundhog to Chandar the Bengal tiger to Onassis the geriatric Giant South American River turtle.

Perhaps the most famous is an animal that members of the Millennial generation and afterward never even met. But he lives in the memories of middle-age and older Milwaukeeans.

According to the Milwaukee Public Library, Samson the gorilla arrived as a baby in Milwaukee in 1950 (back when the zoo was located in Washington Park). He moved to the zoo’s current location in 1959, and would for years grab the attention of delighted, fascinated and (sometimes) terrified zoo visitors when he pounded on the glass of his enclosure.

Samson died of a heart attack in 1981, but Milwaukeeans can pay homage to him with a visit to the Milwaukee Public Museum, where there is a lifelike re-creation of the famous gorilla.

-Amy Schwabe

St. Nick’s Day shoes

If you’ve never lived outside Milwaukee, you may be wondering why a clearly universal celebration like St. Nick’s Day — that perfectly timed mini-holiday to tide you over till Christmas with a few little treats in your stocking or shoes — is being honored in a dedication to Milwaukee things.

But Milwaukee is one of relatively few places that have been lucky enough to hold on to the tradition, along with other cities with large German or Dutch influence, such as Cincinnati; Holland, Michigan; and St. Louis.

The feast of 4th-century bishop St. Nicholas is celebrated Dec. 6. Traditionally, St. Nick is thought to go from house to house on the night of Dec. 5, leaving treats in the shoes of children.

In most places, St. Nick has become synonymous with Santa Claus, and everybody knows he brings treats and gifts just once a year — on Christmas Eve.

For kids new to the city (and their parents), now you know: Milwaukee kids get two mornings in December to wake up to find gifts.

-Amy Schwabe

Milwaukee County War Memorial

The Milwaukee County War Memorial is one of the most recognizable buildings on the city’s Lake Michigan shoreline.

Situated just north of the Milwaukee Art Museum, the War Memorial overlooks the lake from the east side of downtown on East Mason Street, and its plaza is a popular spot for gathering to see lakefront fireworks.

Its mission comes down to six words: “Honor the Dead. Serve the Living.”

The building was dedicated on Veterans Day 1957, the work of Finnish-American architect Eero Saarinen, according to the War Memorial’s website.

The building’s design was “influenced by the abstract geometry of modern French architect Le Corbusier,” according to the Milwaukee Art Museum website.

The building is not only a memorial but a “hub for veteran activities,” the War Memorial website states.

An eternal flame memorial sits in a small pool, illuminating a black granite honor roll that includes names of Milwaukee County residents who have died while serving in the U.S. military.

-Alison Dirr

Ladybug building

On your way to a fancy night out in the Third Ward, take the right path and you’ll come across a permanent trio of massive ladybugs that look like they could be headed the same direction as you.

It’s hard to tell how massive they are, exactly: They’re perched way up on the side of the Milwaukee Building on North Water Street.

At least, it’s a hard calculation looking up at them from the sidewalk or from a car whizzing by.

The fiberglass bugs are each about 6 feet long and 3 feet deep and have been hanging there since July 1999.

They were thought up by John J. Burke to decorate the building that houses the company he started, Burke Properties, according to his obituary.

Not much has been written about them, which is a testament to how many interesting things Milwaukee offers — we take even giant beetles for granted.

-Alison Dirr

Frozen custard

The most quintessentially Milwaukee treat, especially on a hot summer day. (But, let’s be honest: We Midwesterners enjoy a cold cone even when it’s below zero.)

Frozen custard is a step up from your average ice cream because it includes egg yolks that make for a richer texture.

Travel Wisconsin lists Milwaukee as the unofficial “frozen custard capital of the world,” a kind way of saying no visitor should leave the city without trying frozen custard from at least one, if not multiple, locations.

Might we suggest a formal custard tasting?

Three places to start: Gilles, Leon’s and Kopp’s. Each serves a couple of basic flavors every day, plus a Flavor of the Day that’s often more unique.

Gilles Frozen Custard opened in 1938, making it the oldest operating stand in the city, according to Travel Wisconsin. Find it at 7515 W. Bluemound Road, and don’t be shy about taking a look at the full menu of non-frozen treats.

Leon’s Frozen Custard popped up just a few years later, in 1942, and is still operated by the original family, according to its website. The year-round business at 3131 S. 27th St. bills itself as a “classic 1950s-style family owned drive-in, specializing in frozen custard.”

Kopp’s Frozen Custard: Come for dessert, stay for dinner. With locations in Glendale, Brookfield and Greenfield, you’re never too far from the custard shop that’s also known for its massive burgers.

-Alison Dirr

City Hall

You might know it from the 1970s and 80s sitcom Laverne & Shirley, in which “Welcome Milwaukee visitors” is displayed in all-caps across the bell tower in the opening credits.Or, you might just be familiar from passing the iconic building that sits on a triangular slice of land with its north end at the intersection of East Kilbourn Avenue and North Water Street.

The Flemish Renaissance-inspired structure in the heart of downtown Milwaukee was completed in 1895, becoming a fixture of the city’s skyline. It cost about $1 million to construct, according to the city.

Its atrium in the building’s center rises eight stories and serves as the site of city functions and news conferences by officials and those challenging their actions.

On the floors that ascend from the atrium are various city offices, including the Mayor’s Office and the Common Council Chambers where the 15-member council conducts its public meetings. Others include the Assessor’s Office and City Attorney’s Offices.

From the base of the bell tower to the top of the flagpole, the building ascends 393 feet in the air. For a few years after City Hall opened in 1895, it was one of the tallest habitable buildings – if not the tallest – in the nation and world.

The tower holds the bell known as “Solomon Juneau” after Milwaukee’s first mayor, according to the city. The bell was made from church and firehouse bells from around the city and first rang on New Year’s Eve 1896.

-Alison Dirr

Joan of Arc Chapel

In the heart of Marquette University’s bustling campus, a medieval remnant offers respite for the soul.

Joan of Arc Chapel began its life as a place of worship circa 1420 in the village of Chasse, southeast of Lyon, France. Named then after St. Martin de Seysseul, it served the people of Chasse-sur-Rh?ne for hundreds of years before falling into disrepair.

Joan of Arc, the legendary warrior and patron saint of France, is said to have prayed at the chapel in 1429. That was part of its attraction to Gertrude Hill Gavin, who bought it in 1927 and had it moved to her estate in Long Island, N.Y.

Marc Rotjman, a former president of Racine’s J.I. Case Co., and his wife, Lillian, bought the chapel in 1962 and later donated it to Marquette. Over nine months, its 30 tons of stone and 18,000 terracotta roof tiles were carefully disassembled, labeled and shipped to Milwaukee. The reassembled and renamed chapel opened here in 1966. Its nave was lengthened to allow seating up to 60 people; radiant floor heating and electricity were also added.

The Gothic chapel is a striking landmark amid so many buildings centuries younger. But it continues to be an active worship site, with as many as seven Masses a week when classes are in session, including a Sunday afternoon liturgy in Spanish.

-Jim Higgins

Pettit National Ice Center

For many people, just balancing on ice skates is hard ... now imagine maintaining control while skating at 30 miles per hour and racing fellow skaters. That’s the sport of speedskating.

Milwaukee is home to one of the top speedskating facilities in the world: the Pettit National Ice Center. The Pettit is one of only two 400-meter indoor speedskating ovals in the country and is an official U.S. Speedskating training facility. It opened in 1992 and replaced the outdoor Wisconsin Olympic Ice Rink, which occupied the site from 1967 to 1991.

All of the U.S. speedskaters to compete in the past six Winter Olympics have raced or trained at the Pettit Center. The facility has hosted the 2018 and 2022 Olympic Trials and other elite competitions. Over the years, the Pettit has been the home training facility of numerous speedskating greats, including five-time Olympic gold medalist Bonnie Blair, 1994 gold medalist Dan Jansen and four-time Olympic medalist Shani Davis.

The Pettit also boasts two international-size hockey rinks and a 443-meter walking and running track. It is the home of multiple local hockey and skating clubs and offers figure skating, speedskating and hockey lessons for children and adults.

The track is a popular winter training spot for high school, college and adult runners. It hosts track practices, meets and even a 95-lap indoor marathon.

But, if you’re looking for something a little less athletically intense, the Pettit also has ample public skate hours with skate rentals ... perfect for date night or a fun family activity.

-Claire Reid

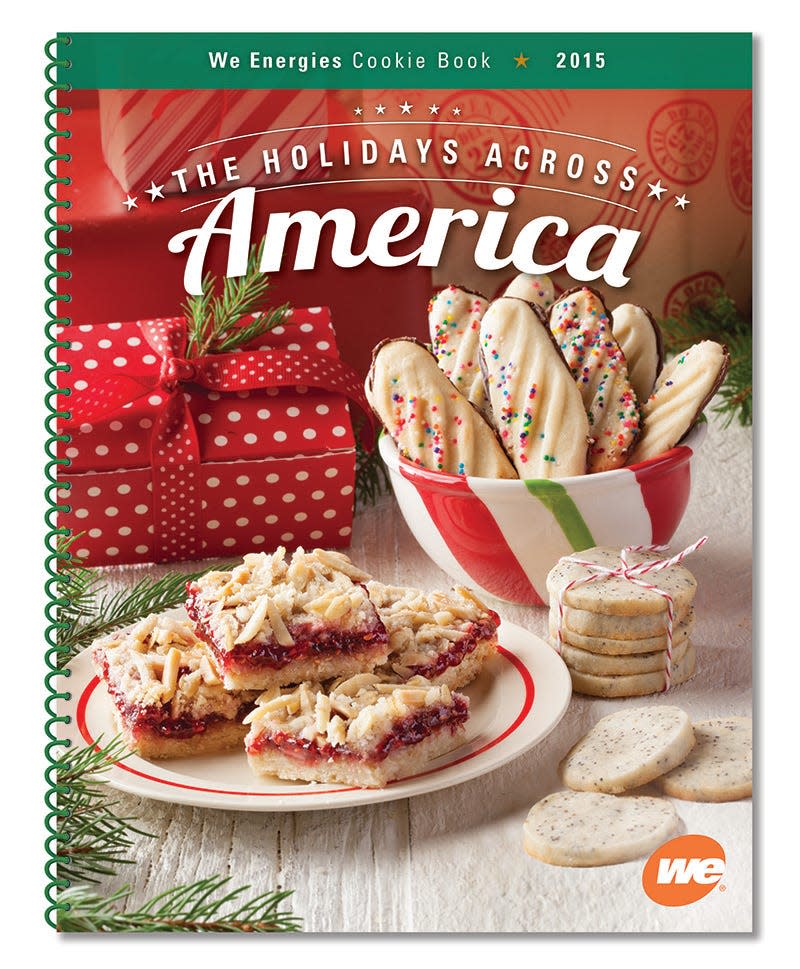

We Energies Cookie Book

Pecan fingers, snickerdoodles, butterscotch bars and more.

Wisconsin residents have been making Christmas treats published in the annual We Energies Cookie Book for nearly a hundred years.

Every year, the company compiles recipes submitted by residents in a book celebrating themes like military service and hometown favorites.

Picking up a copy of the book has become a Christmas tradition in many Wisconsin households. Some longtime Wisconsinites collect copies for years, passing them down through generations.

The We Energies Cookie Book was introduced in 1928, back when the company was known as the Milwaukee Electric Railway & Light Co.

The book was sent to customers to promote the company’s appliances. Through the 1930s, the book grew in popularity and was distributed at the Public Service Building in downtown Milwaukee.

The book has gone through temporary changes over the years. During World War II, the 1942 edition had 14 recipes for wartime cookies, featuring cookie low in shortening and sugar to accommodate for rationing ingredients during the war.

After the 1973 book, the company stopped publishing the book until 1984 due to rising energy costs. The book was published in 1991, 1998, 2002 and restored to its annual printing tradition in 2006. You can find each cookie book digitally archived at we-energies.com/recipes/archive.

-Alex Groth

Pink Squirrel

If you’ve dined at a Wisconsin supper club or visited a traditional cocktail lounge, chances are you’ve heard of (or enjoyed) the Pink Squirrel. In the family of ice cream drinks like the Grasshopper and the Brandy Alexander, the Pink Squirrel has a special Milwaukee connection: it was, as far as anyone can tell, invented at Bryant’s Cocktail Lounge, 1579 S. 9th St., in the 1940s.

With just three ingredients — vanilla ice cream, creme de cacao (chocolate liqueur) and creme de noyaux (almond-flavored liqueur) — the Pink Squirrel is a sweet, nutty, creamy way to drink your dessert.

Both the rosy hue and nutty flavor can be attributed to the creme de noyaux, a liqueur made from apricot, peach or cherry kernels and originally colored with cochineal.

As the story goes, Bryant and Edna Sharp opened Bryant’s as a Miller Brewing tied house in 1936. Within a few years, Bryant abandoned the beer hall approach and transformed the business into the first cocktail lounge in Milwaukee and, quite likely, Wisconsin.

“People who knew him described him as quiet and serious, with a talent and passion for mixology,” a history of the bar says of Bryant Sharp. “He also was known for putting together unique flavors, which he sold to cordial companies.”

It’s only fitting that this classic ice cream cocktail can trace its roots to one of the Dairy State’s favorite drinking establishments.

-Jessie Opoien

The Mural of Peace

Since 1994, drivers traveling north on I-43 have seen the giant eagle and only slightly smaller dove on the wall of a National Avenue building. Back then, Esperanza Unida director Richard Oulahan commissioned artist Reynaldo Hernandez to create a mural to reflect the heritage and aspirations of the south-side community. “The Mural of Peace,” about 80 feet by 150 feet, shows both birds with an olive branch, with a bolt of lightning between them and a background of colored stripes representing flags of different lands.

The mural is painted not on the building’s cream city brick, but on nearly 300 panels affixed to it. After a few years, weather damaged some panels. Contributors to a fund drive to restore the mural included Tippecanoe Elementary students, who raised more than $566 in a penny drive.

The Walker’s Point building at 611 W. National Ave. is now the Mercantile Lofts Apartments. During its conversion to living spaces, modifications were made that created windows on that wall for inhabitants but still kept the bold colors of Hernandez’s design visible.

-Jim Higgins

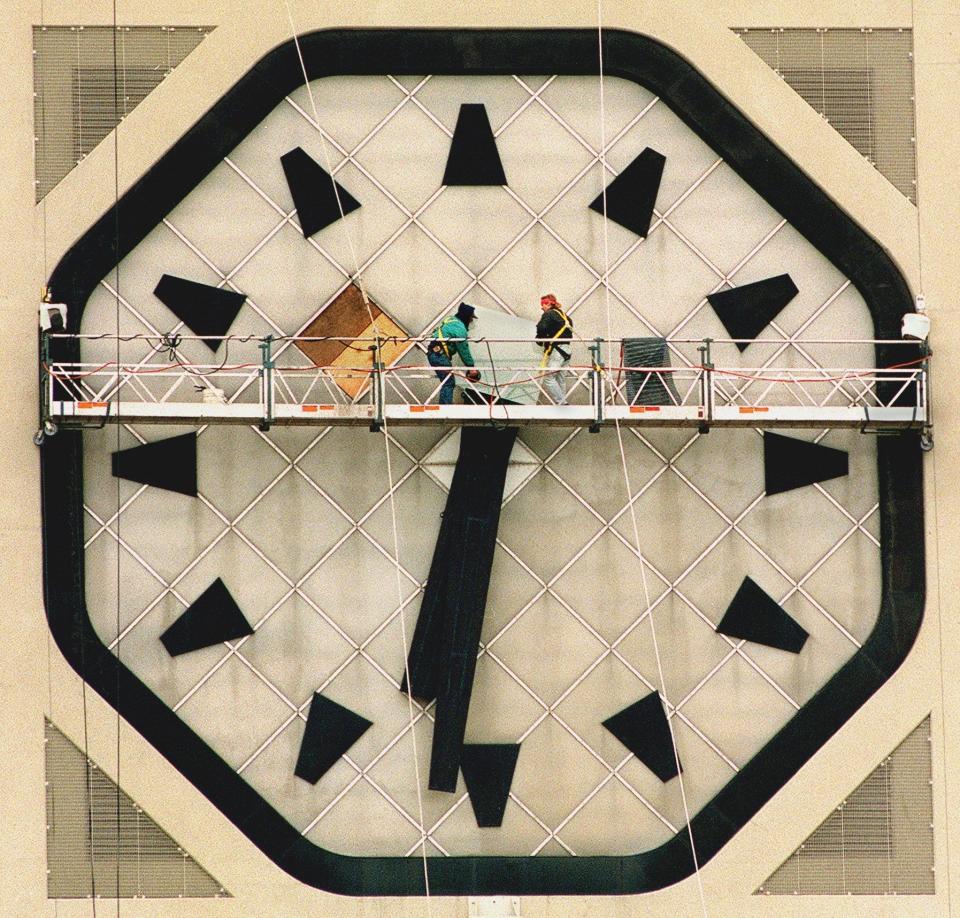

Allen-Bradley Clock Tower

The Allen-Bradley Clock Tower, located on South 2nd Street and just north of Greenfield Avenue, has been a staple of Milwaukee’s skyline and for decades was the largest four-sided clock tower in the world.

Sitting atop what is now Rockwell Automation, the 283-foot-tall clock was revealed on Halloween 1962. The clockworks were built by the Allen-Bradley company, which specialized in electrical controls.

The tower is four separate clocks running on individual motors. About once a month its gears require greasing, but it’s lit by LED bulbs that rarely need to be replaced.

Twice a year everyone moves their clocks forward or back an hour, usually by pushing a button. Changing the Allen-Bradley clock requires a security guard on the outside with a radio looking up at each face while someone with a special key turns four switches inside a room on the first floor.

In its early years it was referred to as the “Polish moon” because of the bright display in a predominantly Polish neighborhood. But over time more Mexican immigrants and families moved to the south side and the nickname was changed to the “Mexican moon” to recognize how the neighborhood has changed.

The clock also illuminated the fight against discrimination in labor in 1968, when the Latino and Black communities joined efforts to fight discriminatory hiring practices at the Allen-Bradley Company.

The protest was started by Father James E. Groppi. Younger Latino residents took up the cause and more activism against the company continued for another year. The march on Allen-Bradley is considered a success, given the consciousness it created and the progress Latinos in Milwaukee have made in the half-century since.

-Ricardo Torres

Paczki

First things first: The correct pronunciation is poonch-ka, says Joe Parajecki, a chef at the Polish Center in Franklin.

And yes, they are similar to jelly-filled donuts, but they’re much richer. Ingredients like sugar, butter, eggs and yeast are put into the dough before giving them up for Lent.

Paczki is traditionally eaten on Fat Tuesday in Milwaukee, though in Poland, it’s actually celebrated on the Thursday before Lent.

“You can’t believe the lines in Poland to get paczki on Fat Thursday. People eat a dozen or more each,” Parajecki said.

Milwaukee is one of the “capital cities of Polish America,” according to Milwaukee historian John Gurda. Two decades after the city was founded, 30 families organized the first Polish Catholic congregation in urban America.

A traditional paczki is the size of a walnut and doesn’t look like a donut at all, Parajecki said. It’s sweet dough wrapped around a prune or filled with rose jam, which is “a very acquired taste. It’s like eating a jar of perfume.”

Prune and raspberry are the most common fillings in America, but there are newer flavors like Nutella and lemon. Parajecki is amazed by how many people who celebrate paczki, even those who aren’t Polish.

He doesn’t care about the paczki vs. donut discussion — more important is tying it to a memory, like sitting around grandma’s table.

“We’re not eating it to debate those things. We’re eating it to remember, we’re eating it to have a good time.”

-Hope Karnopp

Recombobulation Area sign

You just got through TSA at Milwaukee Mitchell International Airport. You’re missing a shoe, toiletries are bursting from your carry-on, and where is that boarding pass again?

A sign past the security checkpoint: Recombobulation Area. An invitation and a space to put your things back in order.

It all started in 2008, when former airport director Barry Bateman told the sign shop he had a great idea.

He was told “recombobulation” wasn’t an actual word, the airport’s director of public affairs and marketing Harold Mester said. Bateman knew that.

“He said, ‘Let’s try to make this a little bit more fun during this stressful experience. If someone gets a chuckle when they go through the checkpoint, then we’ve done our job.’”

As far as Mester is aware, Milwaukee is the only airport to use the “recombobulation” phrase. “Recomposure” is the more technical term, but as Mester pointed out, “that’s an actual word.”

The American Dialect Society once declared “recombobulation” the most creative word of the year. And the term has inspired other branding efforts in Milwaukee, from billboards to beer.

It’s also the namesake of a blog by Dan Shafer. As he put it, recombobulation is the “opposite of discombobulation.” He is often tagged in the many selfies taken in front of the sign.

The sign represents Milwaukee’s sense of humor about itself, Shafer said.

“It’s just one of those quintessentially Milwaukee types of things. It’s just quirky and weird enough and resonates with people.”

-Hope Karnopp

Brandy Old Fashioned

Walk into a Milwaukee supper club or bar on a Friday night and you’ll likely see bartenders lining up rocks glasses and filling each with maraschino cherries, orange slices and a dash of sugar. Next comes a shot of soda water and a muddler. Then, the brandy.

The Old Fashioned cocktail isn’t supposed to be made with brandy, but like anything in Wisconsin, we’ve taken an idea and made it our own. And boy, do we own it.

During an average weekend at the Five O’ Clock Steakhouse on West State Street, bartenders serve more than 100 brandy Old Fashioneds, general manager Hegel Terron told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

During the week, the daily average probably tops at 75, he said.

At the Packing House supper club on East Layton Avenue, general manager Chris Wiken said he’s ordering two cases of Korbel brandy per week.

The vast majority of customers are asking for brandy Old Fashioneds sweet, Wiken said. But in recent years, customers are getting a bit more picky about which brandy they want – ordering Milwaukee’s Central Standard or even comedian Charlie Berens’ spirit.

On a good Friday night, the Packing House is filling a couple hundred rocks glasses with Wisconsin’s favorite cocktail. In a year’s time, that’s tens of thousands, Wiken said.

“I cannot keep Korbel on hand. It just flies out the door,” he said. “Friday night is probably when we sell the most because the pairing with the fish fry is a really good pairing.”

-Molly Beck

Bubbler

If you’re not from Wisconsin, there are a few ways to give yourself away. First: Order a bourbon Old Fashioned instead of brandy sweet. Second: Wear a Cardinals hat. Third: Ask for directions to the nearest water fountain.

Inexplicably, public water fountains here are called bubblers and pretty much only here. There are some in Rhode Island, for some reason, but the vast, vast majority of the nation adopted “drinking fountains” and “water fountains.”

Milwaukee appears to be ground zero for the use of bubbler, according to UW-Madison’s Dictionary of American Regional English. Its origins are fuzzy but may be tied to its use by Kohler Co., one of Wisconsin’s most famous brands – a manufacturer of faucets among other water-related products.

The company in 1914 promoted a water fountain created by Kohler as being fitted with a “continuous flow bubbler,” according to the UW-Madison dictionary.

A former dictionary editor in 2015 told Wisconsin Public Radio that “bubbler” was used especially in the southeastern area of the state starting in the mid 1910s. More than a century later, we’re still using bubblers.

-Molly Beck

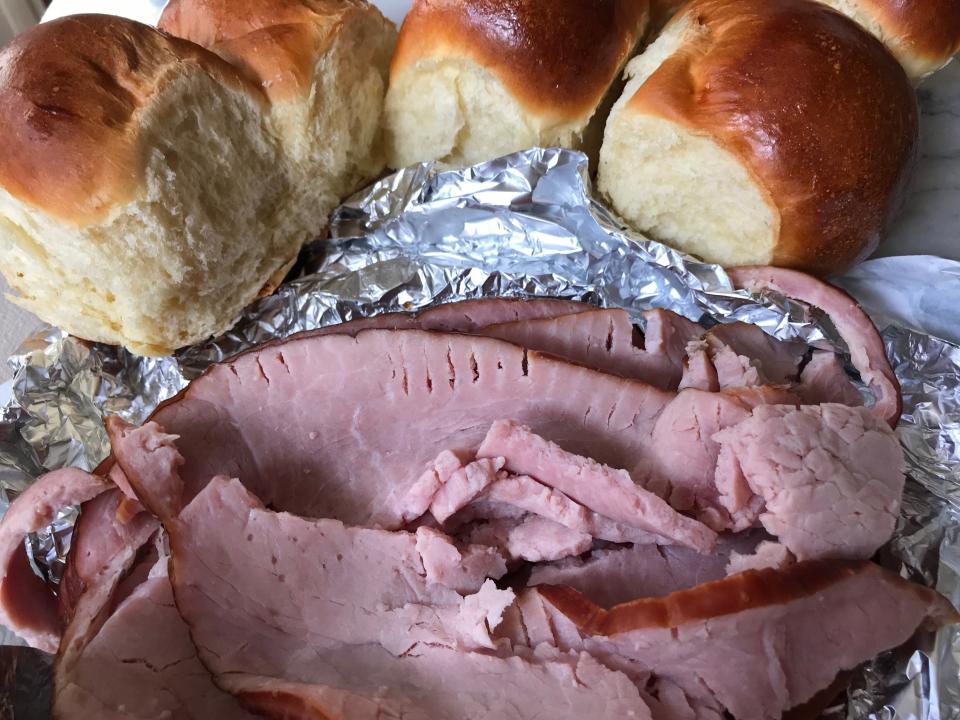

Hot ham and rolls

Sundays in Milwaukee have a smell: buttery, fresh-baked rolls.

After church, it’s tradition to pick up what’s known as hot ham and rolls – an end-of-weekend feast with origins in the cream city’s German or Polish roots, depending on which bakery owner you speak to.

For less than $30 at Grebe Bakery, for example, you can get three pounds of ham, 18 rolls and two pounds of potato salad.

The meal is part of Milwaukee’s identity, so much so that former Gov. Scott Walker made it part of his politico persona along with other attributes Walker promoted to assure voters he was as Wisconsin as they were.

He tweeted nearly 20 times about procuring hot ham and rolls from now-shuttered Fattoni’s deli after church in Wauwatosa during his first term as governor.

Brian Schwellinger, president of Badger Ham, which provides the hams for many bakeries’ meal deals, told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel in 2021 the hot ham and rolls tradition is likely rooted in religion.

“There were so many churches that the church tradition was a strong part of the community, and after service is when you had your first meal of the day,” Schwellinger said.

-Molly Beck

UWM research vessel

The Great Lakes may seem like an limitless resource, but the world’s largest surface freshwater system faces major threats from pollution, climate change, invasive species and overexploitation.

And to understand and protect it, scientists need to be out on the water.

The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee School of Freshwater Sciences has made its mark on Great Lakes research. It’s the only graduate school of freshwater sciences in the country and one of only three in the world.

UW-Milwaukee’s main research vessel, the Neeskay, is the only research vessel out on the lakes year-round.

Before the Neeskay started powering scientific expeditions in 1970, it was an Army T-boat used during the Korean War. Its name comes from the Ho-Chunk word for “pure, clean water.”

Scientists use the Neeskay to study algae blooms, invasive quagga and zebra mussels, and microbes that live out in the lakes. It’s also used to deploy buoys that monitor weather and lake characteristics, like temperature and nutrients.

But the Neeskay, along with a fleet of small boats, are only just the start. The university has been raising money since 2016 to build the Maggi Sue, which will become the most technologically advanced freshwater research ship in the country.

The Maggi Sue is expected to open many doors in understanding what’s going on out in the Great Lakes.

-Caitlin Looby

Bango

The Bucks’ mascot has delighted crowds with dunks and stunts, from the Milwaukee Arena to the Bradley Center to Fiserv Forum, for almost 50 years.

Bango made his debut in the team’s 1977-78 home opener — which pitted the Bucks against the Los Angeles Lakers two years after NBA legend Kareem Abdul-Jabbar left Milwaukee for L.A.

Named for the call the team’s original radio announcer, Eddie Doucette, made when players made a long-range basket, Bango was the moniker chosen by fans in a contest.

In the decades since, he’s gone through several makeovers and celebrated many milestones.

In 1984, he got his first car (it’s unclear whether he was old enough to drive; we’re not sure how deer aging equates here). He got married in 2002, and welcomed Bango Jr. in 2005. Two years later, Bango and Bango Jr. first appeared in their inflatable forms. 2010 was a big year for Bango: he nailed a few new dunks and was honored as the NBA Mascot of the Year.

The next few years brought more cervid celebrations: Cartoon Network’s “Most Awesome Mascot,” a human hamster ball dunk and a featured role on the Hulu “Behind the Mask” documentary. There were also a few mishaps along the way — a torn ACL and a broken rim during a Badgers halftime show.

Whether he’s wearing a sweater or a full uniform with the number 68 (for the team’s first season), doing acrobatics on the court or making appearances in the community, Bango is Milwaukee’s most dominant deer.

-Jessie Opoien

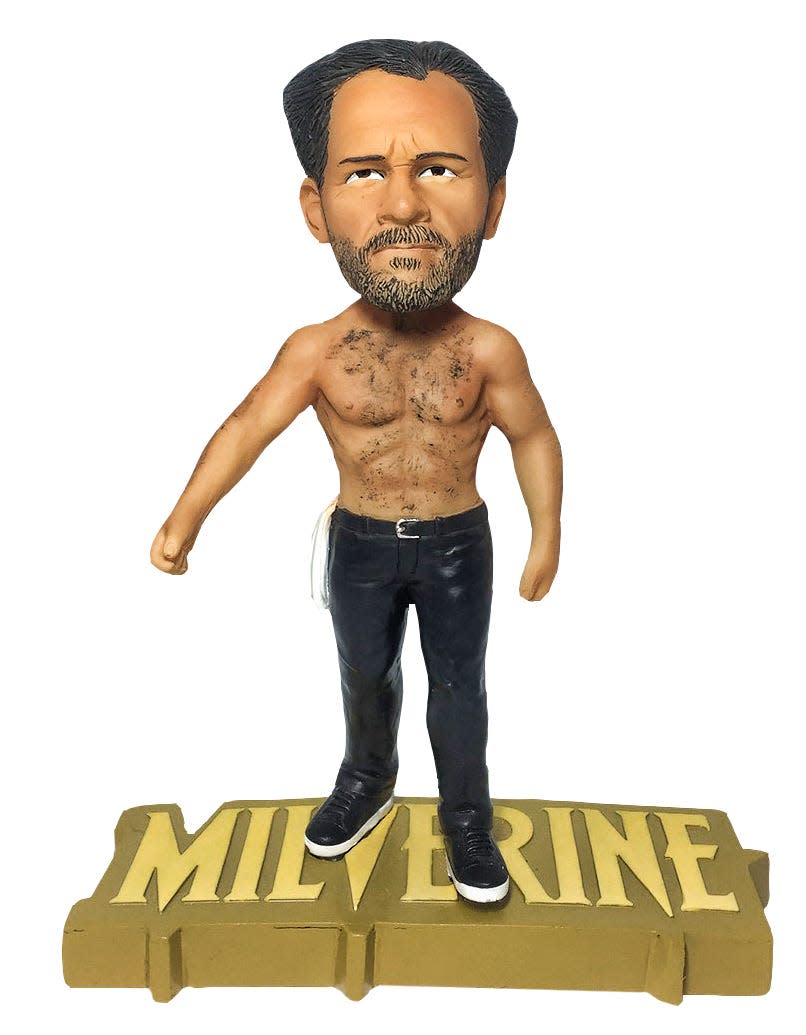

David Gruber giveaway T-shirt

One call, that’s all.

It’s not a particularly unusual slogan. Milwaukee isn’t home to the only law firm that has used it. But say those words around Milwaukee, and you’ll get immediate recognition, and probably a smile. Is it weird that simply saying the slogan or name of a personal injury lawyer, albeit a locally famous one, can cultivate ... joy?

David Gruber, the lawyer in question, has been using the slogan in TV advertisements since the late 1990s, born from a collaboration with a Dallas media company.

He looks into the camera and punctuates every ad with those famous four words, a catchphrase that has become the dictum around which his entire brand has been constructed.

The celebrity lawyer can be found in the first few rows of Milwaukee sporting events and has partnered with just about every major sports operation in the city, a nod to his lengthy interest in athletics.

And it’s not hard to score a “Gruber Law Office” T-shirt at a sporting event or at street fairs around the city, the perfect giveaway to spread the Gruber gospel and let everyone around you know how Milwaukee you are.

-JR Radcliffe

Grill

In Milwaukee, the herald of winter’s thaw is not that growing patch of green on a lawn or the first magnolia blossom peeling open or that last crusty pile of parking lot snow.

No: It’s the first aroma of match meeting propane, that sizzle of cold meat on hot grates, the collective tower of smoke rising above the interchange at American Family Field.

It’s spring. It’s grilling season.

You don’t have to be the one grilling to enjoy its benefits. The first sunny day in March when it’s light past 5 p.m. — that’s when it happens. The first smells of a neighbor lighting charcoal and laying down some hamburger patties.

“Someone’s grilling,” you say, and you smile.

Grill smells permeate the air in Milwaukee from spring to fall. On a summer day, you can drive around with the windows down and you know when the neighbors are gathering. You can be sure there’s a cold beer in a koozy and the charcoal is heating up.

And then there’s the tailgate, that communal grilling session. Many urban ballparks have parking garages or no parking at all, thus no opportunity to truly enjoy the baseball experience. But the tailgate endures in Milwaukee. On a sunny day (or rainy or snowy, we’re hardy people), the American Family Field parking lots are packed with canopies, games of corn hole and folding chairs all huddled around one thing: the grill.

-Lainey Seyler

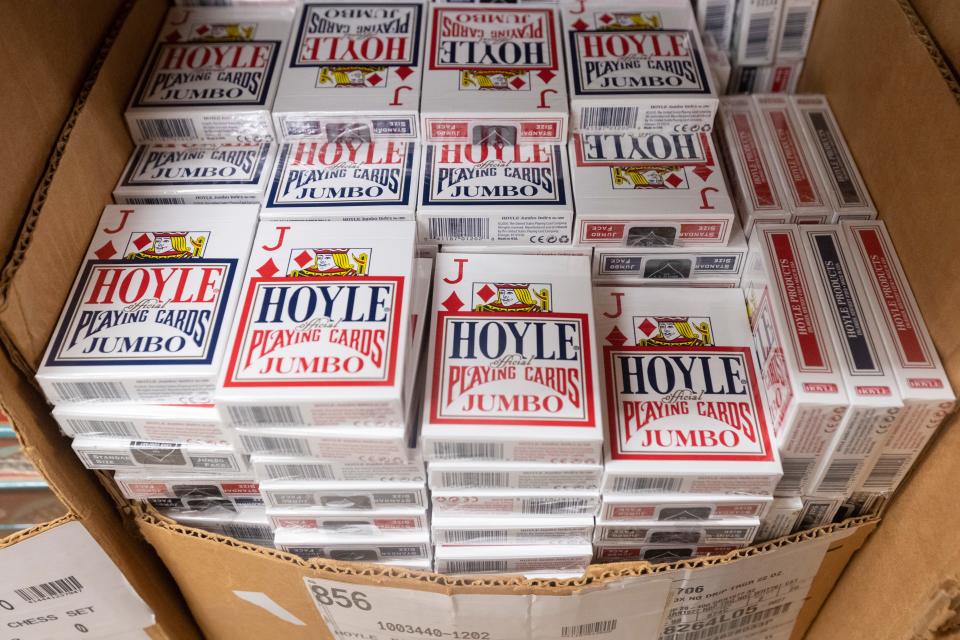

Deck of sheepshead cards

Are you a “call an ace” player or a “picker and jack of diamond” player when you sit down at the sheepshead table? And if you don’t know what those phrases mean, you probably aren’t familiar with “leaster,” “re-crack” or “schmear.” To know the card game is to speak a certain kind of Milwaukee dialect.

The trick-taking game often features five players but has its share of variants, with different rules and terminology for different parts of the state. But this isn’t a pastime that’s achieved a high level of popularity outside the state’s borders.

Like Milwaukee, sheepshead’s roots are deeply German — the game is Schakopf in its native country, and the unofficial history involves disgruntled peasants inventing the game that gave kings a lower ranking. Sheepshead arrived in Milwaukee with a large population of German immigrants, many of whom worked in brewing.

The card game’s patron saint, Bob Strupp, published “How To Play ‘Winning’ 5 Handed Sheepshead” in 1983. The lifelong Milwaukeean attended Common Council meetings to advocate that the game should be declared Milwaukee’s official card game, a campaign that proved successful.

For more than a quarter century, Glendale has claimed to serve as home to the largest sheepshead tournament in the world; a nurse from Kewaskum won in 2024.

-JR Radcliffe

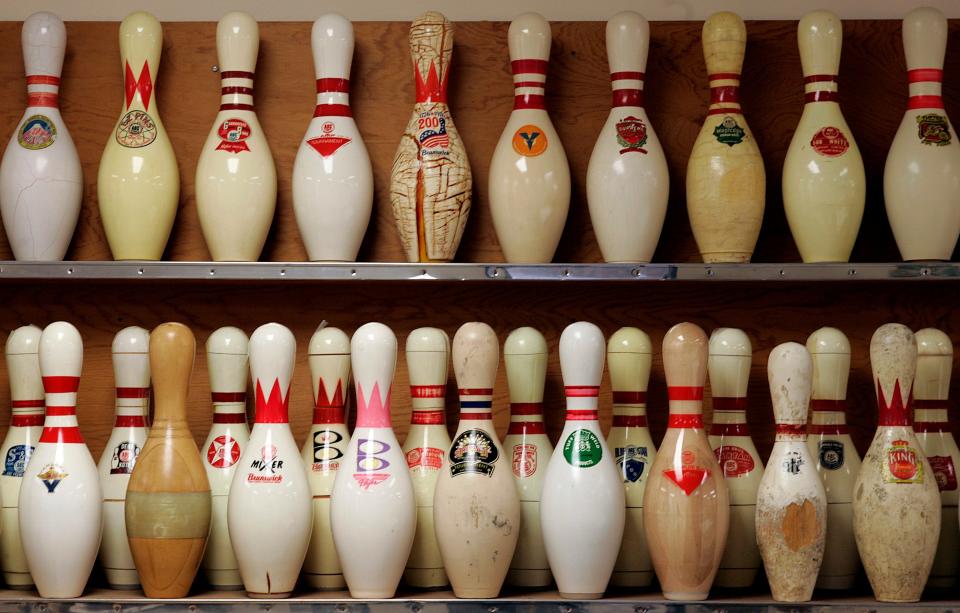

Bowling pin

There was a time when Milwaukee had earned the title as “The Bowling Capital of America.”

Evolving from German “kegling,” German-Americans helped raise the game’s popularity in the states, and a city like Milwaukee with a deep German heritage was quick to adopt. But as nationwide popularity fell, Milwaukee’s bowling culture wasn’t ... well, uh, spared.

The United States Bowling Congress, which once called Greendale home, moved to Texas in 2008. The PBA Tour, once sponsored by Miller Brewing, stopped making the city a regular tour stop after 1990, bowling centers closed and WTMJ’s wildly popular “Bowling With the Champs” TV series, which made local celebrities out of top bowlers and served as a precursor to reality competition television, ended after 41 years in 1995.

But bowling’s history remains visible around the city and state. Milwaukee tavern The Holler House houses the oldest sanctioned bowling alley in the United States, and the miniature version of the sport still has a place at legendary Koz’s Mini Bowl, home to “the last duckpin bowling in the U.S.” The Vulcan Corporation in northern Wisconsin became a major manufacturer of bowling pins.

And the PBA even returned for a stop in Wauwatosa in 2023.

-JR Radcliffe

MECCA floor

It’s the floor that made Milwaukee famous.

Designed for $27,500 by New York pop artist Robert Indiana — a man with the perfect name to match the flamboyance of the masterpiece — the MECCA floor was a controversial addition in 1977. The Milwaukee Exposition and Convention Center (known today as the UW-Milwaukee Panther Arena, but then abbreviated as the MECCA) served as home to the Milwaukee Bucks and Marquette men’s basketball team. Marquette basketball, known for its eclectic uniforms and the fiery personality of recently retired head coach Al McGuire, was the perfect match for the look.

The floor featured two giant Ms consuming either half of the court, somewhat hidden in the two-toned yellow paint scheme, a red bull’s eye at center court and blue lettering for “MECCA” wrapped twice around the center circle. Dark red for the lanes, dark blue for the sideline and dark green for the perimeter.

The gaudy floor didn’t quite fit everyone’s aesthetic tastes immediately (including new MU head coach Hank Raymonds), but it was a hit with plenty of fans (and Bucks coach Don Nelson). It became part of the Milwaukee color palette until the Bucks moved into the Bradley Center in 1988. The Bucks re-created the floor for a “Return to the MECCA” game in 2017, a return to the building that harbored the 1971 NBA champion and 1977 NCAA champion.

Indiana rose to fame because of his “LOVE” sculpture, but the MECCA floor remains a distinctly Milwaukee concept.

-JR Radcliffe

Bay View iron well

There are many places around Milwaukee where you can take a drink of history, including many brewery tours.

But there is also a non-alcoholic option nestled between Wentworth Avenue and Superior Street in Bay View:

The Pryor Avenue Iron Well, a source of drinking water since 1882.

Originally drilled to provide drinking water and fire protection, it’s the last surviving public well in the city, according to the Historical Preservation Committee. The city named it a historic structure in 1987.

While the well is just a short walk from Lake Michigan, the water actually comes from an aquifer nearly 120 feet underground.

The iron-rich water tastes a bit different than city water. The water is clear with a distinct metallic taste. Sometimes there might be a faint smell of sulfur.

Elevated levels of strontium, a natural element found in bedrock, were detected in 2015. But according to the EPA, the levels are only an issue for sensitive populations after drinking the water over the course of a lifetime.

Overall the water is safe to drink, according to Milwaukee Water Works and the Environmental Protection Agency.

In fact, the well was a lifeline for many during the 1993 cryptosporidium outbreak that ravaged the municipal water supply.

So fill a jug or take a sip from the bubbler. Just ignore the penny-like metallic notes.

-Caitlin Looby

Milorganite

The drive along the Hoan Bridge offers some of the best views of the Milwaukee skyline and Lake Michigan.

And if the wind blows in the right direction, it’s also where you can get a good whiff of Milwaukee’s signature funky scent.

No, Eau de Milwaukee isn’t hops, brats or cheese curds. It’s Milorganite, a lawn and garden fertilizer made from our very own wastewater.

The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District started making Milorganite – named after Milwaukee organic nitrogen – at the city’s sewage treatment plant on Jones Island in 1926.

The city used a new method to treat wastewater, called the activated sludge method, which mixed microbes with sewage and air to remove 95% of the bacteria from the city’s sewage and 90% of the solids.

After wastewater enters the Jones Island Water Reclamation Facility, microbes are added that feast on the organic material. When the microbes die they settle to the bottom, leaving clean water above that is returned to Lake Michigan.

Water is squeezed out of the microbes before they are dried and turned into pellets that become the nitrogen-rich fertilizer sold around the country.

Turning this waste into fertilizer has kept 10 billion pounds of waste out of landfills since 1926, according to the sewerage district.

-Caitlin Looby

Bastille Days Eiffel Tower

A mark of Milwaukee’s annual celebration of Bastille Day, the 43-foot Eiffel Tower that appears each year in Cathedral Square Park is a testament to the city’s determination.

The tower has had to go through several rounds of repairs and reinforcement to keep up its yearly appearances. There have been a few years that an inflatable Eiffel Tower took the real one’s place, but it always returns, as it did in 2023 after a year of repairs.

The tower was initially built as part of an indoor department store display in the late 1980s, possibly in Minneapolis, according to a 2022 OnMilwaukee report.

The tower was never supposed to be permanent, and it definitely wasn’t meant to be assembled and disassembled each year for its appearance at the festival. But that won’t stop the tower, nor the organizers of the Bastille Day celebration, who are asking for donations to complete more repairs and restoration.

The Eiffel Tower is far from the only French-themed activity of the weekend. There’s also the Storm the Bastille 5K run and walk, in addition to can-can dancers and plenty of French fare. The celebration is meant to honor the storming of the Bastille, the 19th-century French prison, an event that helped to start the French Revolution.

-Laura Schulte

Fish fry

Go into about any Milwaukee restaurant, tavern or even the corner bar on a Friday after work, and you’re likely to see diners enjoying fish alongside a classic Wisconsin Old Fashioned.

The crisp crunch of walleye, perch, cod or maybe even bluegill, paired with some type of potato, coleslaw, tartar sauce, a lemon wedge and perhaps a slice of rye bread.

Fish fries are actually so popular in Wisconsin, Gov. Tony Evers declared Feb. 16, 2024, as Friday Fish Fry Day, honoring the history of the meal. According to his proclamation, the fish fry became popular when a large population of Catholic European immigrants settled in Wisconsin in the 1800s and needed something meat-free to eat on Fridays during Lent.

Then, during Prohibition, the meal helped to keep Wisconsin’s breweries and taverns alive, too, further cementing the tradition.

Today, fish fries in Milwaukee and throughout Wisconsin serve as a weekly opportunity to gather with friends and family at your favorite establishment, catch up and swap stories over a plate of deep-fried fish.

-Laura Schulte

Bernie’s Chalet at Lakefront Brewery

A piece of Milwaukee’s baseball history, Bernie Brewer’s Chalet was once one of the crowning jewels at County Stadium. Bernie Brewer would slide out of the chalet and into a giant stein of beer after every home run or if the Brewers won the game, setting the stage for celebration.

Now, the chalet is a part of another popular Milwaukee stop: Lakefront Brewery. It’s a stop on the brewery’s tour through the facility, and now it can even be booked for a romantic dinner for two, overlooking the kettles of the brewery.

Lakefront Brewery was born in 1987 out of something distinctly Wisconsin: some 55-gallon stainless steel drums and used dairy equipment. Jim and Russ Klisch, the founders, sold one barrel of beer to a tavern within rolling distance of the brewery.

Lakefront has come a long way. Now housed at 1872 N. Commerce St., the brewery has produced as many as 46,848 barrels in one year (2017) and offers 20 different beers across 30 states, and even some other countries, according to the brewery’s website. The brewery also offers tours for over 80,000 people a year, and was the first to offer beer before, during and after the tour.

-Laura Schulte

Cannibal sandwich

If you’re not from Wisconsin, this food item may repulse you – or at least make you do a double take.

But here in Milwaukee, it’s a delicacy.

We’re talking about the cannibal sandwich: a base of rye bread topped with fresh raw beef, chopped onion and a little salt and pepper. It’s deeply rooted in the state’s history and still enjoyed today.

Versions of the sandwich also exist in Germany, where it’s called mett or hackepeter. The idea is thought to have been brought over by German immigrants to Wisconsin when they arrived and began to establish cattle farms, giving them easy access to fresh meat.

Today, it’s still a popular tradition served during holidays and family gatherings — though not without a little scrutiny. Eating raw meat, after all, is a health risk. The Wisconsin Department of Health Services reminded residents of as much in a 2020 tweet that went viral as those unfamiliar with the sandwich gawked.

But those who enjoy it are likely to keep paying homage to their heritage. Some Milwaukee delis and butcher shops sell thousands of pounds of high-grade raw beef around the holidays to eager customers.

Tasty or mildly terrifying, it’s one of the city’s cultural staples.

-Madeline Heim

Mr. Perkins Family Restaurant

If you’re looking for a home away from home, look no further than Mr. Perkins Family Restaurant.

While the fried chicken and collard greens are rave-worthy, the real showstopper at this 55-year-old establishment is the customer service.

When the restaurant, located on the corner of West Atkinson Avenue and North 20th Street, opened in 1969, owners Willie Sr. and Hilda Perkins created a family feeling that brings in regulars and even politicians and celebrities like Michael Jordan and Charles Barkley.

A staple for the Black community in Milwaukee, the restaurant serves comforting southern flavors that can be hard to find here in the Midwest.

When Willie Perkins Jr. took over in 1999, he continued creating that feeling, filling customers in on the latest news about the Green Bay Packers and the Milwaukee Bucks.

When Willie died in 2010, his wife, Cherry, took over. Now, Cherry and a small team — her sister, her son and one other worker who might as well be family — continue the legacy, remembering regulars’ names and orders and creating community in addition to delicious food.

-Zoe Takaki

Cheesehead

It’s synonymous with Green Bay Packers fandom today, but the Cheesehead made its first appearance at a 1987 Milwaukee Brewers game — a completely, ahem, organic creation.

The legend is well-known now: Ralph Bruno went to his mother’s south-side Milwaukee home to help her reupholster a couch. When he took it apart, he thought the foam inside looked like cheese — so, naturally, he cut a piece into a triangle, burned some holes into it and spray-painted it yellow. It was a self-deprecating homage to an insult Wisconsin sports fans received from their neighbors in Illinois.

To Bruno’s friends’ surprise, the hats were a hit. So he made more, and sold them from a garbage bag at the next game he attended. That led to neighborhood retail sales and, eventually, the creation of Foamation Inc. — and a robust variety of Cheesehead variations including cowboy hats, baseball caps and koozies. The Packers acquired Foamation in 2023, solidifying the relationship just like a good curd.

Over time, the Cheesehead has inspired song parodies and been featured in a Lil’ Wayne tribute to the Green & Gold (er, Yellow). It’s been worn or displayed by famous figures including George W. Bush, Jodie Foster, Phoebe Bridgers and John F. Kennedy Jr. And despite Chicago Bears fans’ efforts to shred them with their answer — the Graterhead — Cheeseheads are here to stay.

-Jessie Opoien

The Hop

Two parallel metal tracks stretch across the roads in downtown Milwaukee, soaking up the heat of the summer and the frost of the winter. You wait a bit, a streetcar the length of two buses slides slowly toward you.

You wonder if it’s automatic, running robotically and beeping like that, until you see a conductor in the front seat and you let out the breath you’d been holding — it will stop at traffic lights and behind cars. On the side of the car golden letters read in all caps: “THE HOP.”

The Hop is a fixed-transit network that gives a ride to more than 1,000 people a day, going to various destinations in downtown Milwaukee. Its route stretches from Veterans Park to Milwaukee Public Market and expanded to the lakefront in spring 2024.

The Hop is a relatively new addition to the city, having started running in 2018. But it’s a continuation of a long history of streetcars in the city — the first electric streetcar started giving rides in 1890 and for decades was the primary form of transportation.

Today, The Hop has become a staple of downtown life, whether or not you ride it.

-Eva Wen

Jones Island salt pile

If Milwaukee was going to have a mountain, it’s fitting that that mountain would be made of the thing that keeps the city moving during its cold, icy winters: road salt.

Along with the pungent aroma of Milorganite, the gigantic salt piles are likely what most Milwaukeeans associate with the city’s Jones Island, once home to a commercial fishing village of Polish immigrants.

Today, the island holds tens of thousands of tons of road salt delivered to the Port of Milwaukee for use in melting icy streets, highways and interstates across Wisconsin.

In recent years, concern has grown about excess road salt washing off of streets and into nearby bodies of water, including Lake Michigan.

Roughly 2.2 billion pounds of chloride (a component of road salt) flush into the lake each year, according to a December 2021 study. And while the size of the lake helps dilute the salty pollutant, smaller tributaries aren’t so lucky. In the Milwaukee River basin alone, for example, over 100 miles of waterway are impaired by chloride, some with levels several times that which can be toxic to fish and aquatic life.

Many municipalities and private businesses, including some in the Milwaukee area, have made adjustments to reduce their salt use in the name of protecting freshwater, including brining, where salt is mixed with water before being applied to roads.

-Madeline Heim

Cousins Subs

A Milwaukee sub sandwich staple, Cousins Subs began in 1972 when cousins Bill Specht and Jim Sheppard opened their first shop at 60th Street and Silver Spring Drive to “bring their favorite style of sub sandwich from the East Coast to their new hometown of Milwaukee,” the company’s official story reads.

Cousins offers classics like the Italian Special, Pepperoni Melt and Tuna, plus specialties like Wisconsin Cheese Steak. And in Milwaukee, Cousins stands apart from national sandwich chains — not only for its local roots but its very-us offerings like Wisconsin mac and cheese, shakes and fried cheese curds.

The Cousins sandwich — carrying the slogan “Better bread. Better subs” — is so popular the company had to cancel a free sub promotion in early 2024 when restaurants couldn’t keep up with the overwhelming response.

-Erik S. Hanley

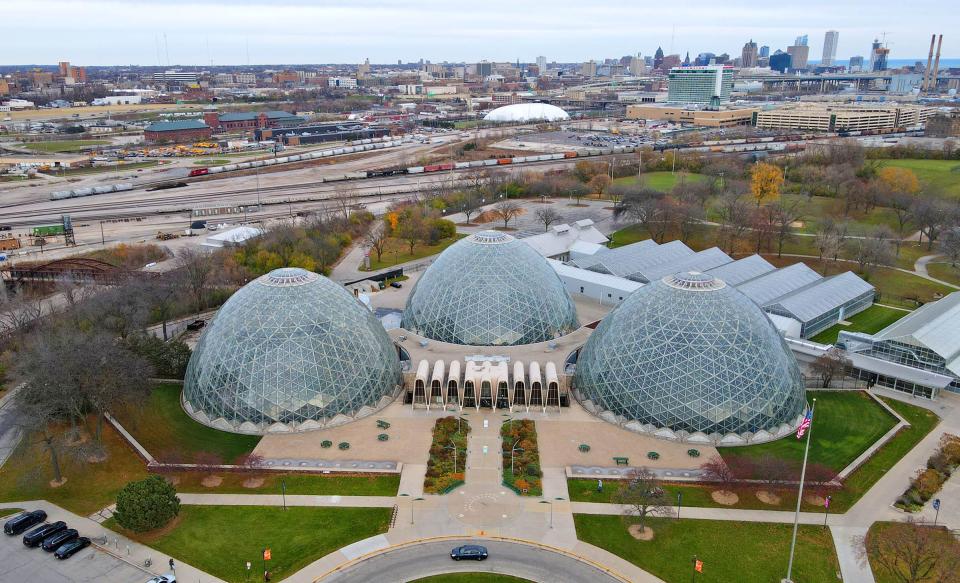

The Domes

Wouldn’t you like to go to Orlando in mid-February? Not for Disney, but for the greenery, the smell, the sense that things are alive.

That’s what you’ll find in the Tropical Dome — where you can sit in the sun with a book in hand, no matter the season. Roll up your sleeves, find a bench and relax.

In contrast, if you’re always too hot, the Desert Dome stays 50 degrees through the winter. If you have kids with you, think Show Dome and occasional choo-choos.

The three beehive-shaped Domes, aka Mitchell Park Horticultural Conservatory, sometimes seem the forgotten child of Milwaukee attractions. They’re fighting for their future. Yet even the common name – Domes – has a Milwaukee humility about it.

With more than 1,800 plant species, cleverly described with signage, the Domes are worth a walk.

Since Lady Bird Johnson dedicated the Domes in the fall of 1965, other accolades have followed. In 2017, the National Trust for Historic Preservation gave “National Treasure” status to the Domes.

And the Domes have a characteristic that Milwaukeeans love: They’re cheap.

The priciest admission costs $9, and parking is free, unlike at the stadium, the zoo, or almost the entire downtown.

-Pete Sullivan

Brewers Racing Sausages

Bratwurst. Polish. Italian. Hot Dog. Chorizo.

Brewers fans have been cheering for one sausage or another during their race at the bottom of the sixth inning for more than 30 years. What started as a cartoon competition on a County Stadium scoreboard made its way to Miller Park (now American Family Field) as a treasured Milwaukee tradition.

The real-life Racing Sausages debuted June 27, 1993, and gave rise to live-action mascot races throughout Major League Baseball, such as racing presidents and pierogis. The idea to take the links from the scoreboard to the field came from Michael Dillon, who worked as a graphic designer with McDill Design at the time, and their first appearance was a surprise to almost everyone in the ballpark.

The matchup of 7-foot-tall encased meats was sponsored by Klement’s until 2018, when Johnsonville took the reins.

The sausages have had their ups and downs over time. Among the wurst: In 2003, then-Pittsburgh Pirates first baseman Randall Simon whacked the Italian Sausage with a bat, causing the Hot Dog to tumble as well. Both finished the race, thanks to an assist from the Polish (the Bratwurst won). There was also the time in 2013 that the Italian Sausage’s casing (er, costume) was stolen (and ultimately returned) in Cedarburg. A few years later, Hot Dog took a tumble and brought Chorizo and Bratwurst along with him. And as recently as the team’s 2024 season opener, Minnesota Twins outfielder Byron Buxton narrowly missed being taken out by Bratwurst.

No matter the wiener, Milwaukee will always love its Racing Sausages.

-Jessie Opoien

George Webb hamburger

Legend has it George Webb first predicted Milwaukee’s baseball team would win 12 games in a row back in the 1940s – and maybe even hinted that his namesake restaurant would give out free hamburgers to celebrate the winning streak.

Decades passed before his prophecy came true, but in April 1987, the Milwaukee Brewers finally pulled off the feat – and some 168,194 people lined up outside George Webb Restaurants for free burgers. It’s hard to describe how big of a deal it was to those who didn’t experience it firsthand, but trust us, there are few things us frugal Wisconsinites love more than free stuff. Combine that with baseball and burgers, and it basically felt like a street festival.

While most people ate their free burgers, some decided to save the historic freebies for posterity. One man even had his bronzed for his father. Others threw theirs in basement freezers, only to find them decades later. (This reporter would like to apologize to her older brother, Paul, for throwing out his 20-year-old frozen burger instead of bronzing it.)

The Brewers did it again in 2018, and for only the second time in Milwaukee history people lined up to celebrate and claim their free burgers.

Even when it’s not promising free burgers, George Webb is a beloved burger joint open 24 hours a day. Still, any long Brewers winning streak definitely starts to feel like a free-burger watch party.

-Mary Spicuzza

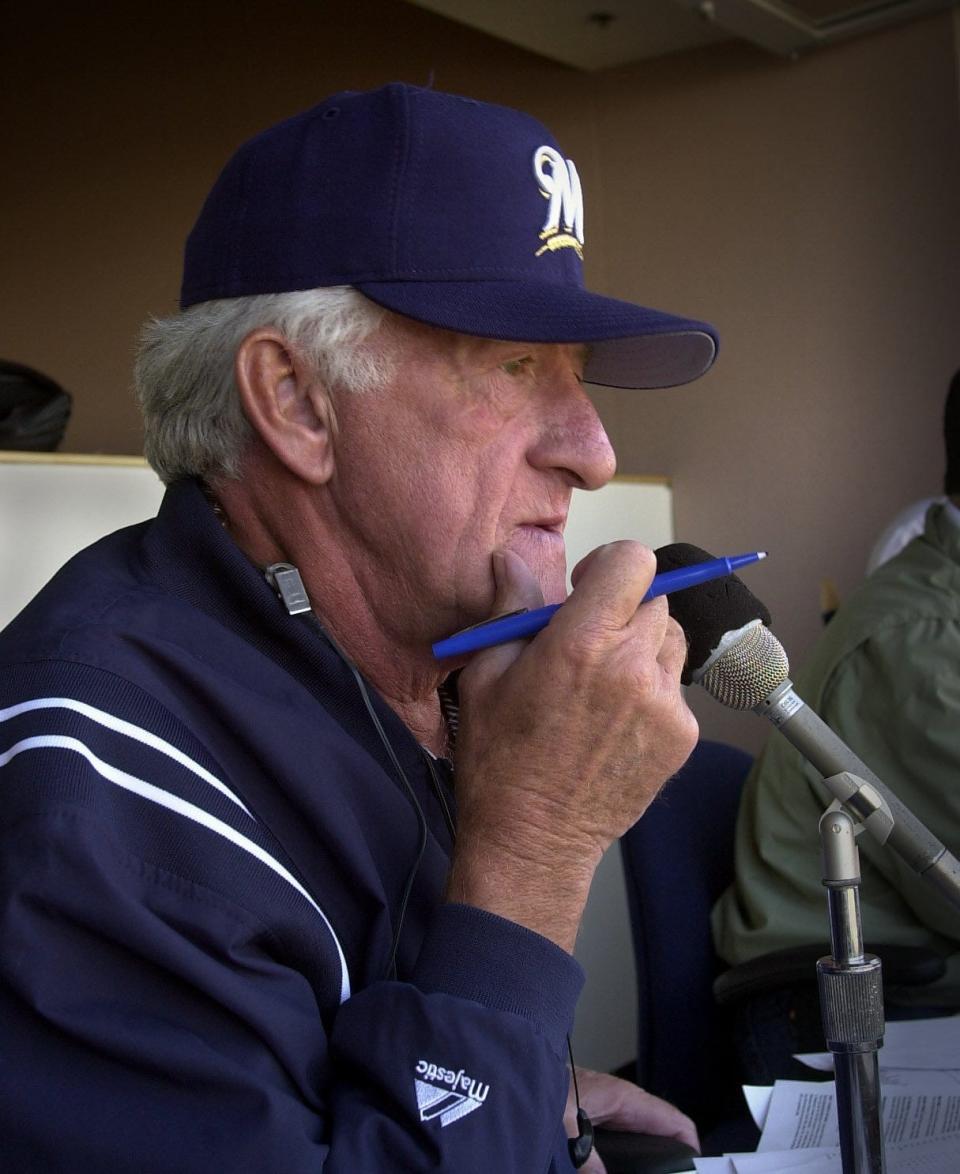

Bob Uecker’s microphone

Bob Uecker didn’t sign a broadcasting contract with the Milwaukee Brewers until 2021.

Before then, it was handshake agreements with owners Bud Selig and Mark Attanasio.

Ueck tries not to take himself too seriously. It’s part of the reason why he is such a revered figure among Americans, specifically Milwaukee natives and Brewers fans.

“Mr. Baseball” being the butt of the joke is why the “Uecker seats” named in his honor are considered the best worst seats in baseball. “I must be in the front row,” Uecker said to a stadium usher in a mid-’80s Miller Lite commercial who told him to move to where his ticket was located — way up high.

Uecker seats used to be sold for as little as $1, but there was a catch: Fans would need to wait hours before first pitch at the box office to get their hands on the tickets, and the seats were less than desired — up in the nosebleeds with an obstructed view, but near Uecker’s statue.

Uecker, 91, has been speaking into his microphone for the Brewers radio broadcast since 1971. He wouldn’t want to hear it, but his mic serves as a symbolic gold standard for not only sportscasters but also the entertainment figures we allow into our living rooms.

He’s been a regular guest on “The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson,” hosted “Saturday Night Live” in 1984 and had roles in Hollywood films — his delivery of “Juuust a bit outside” in the 1989 cult classic film “Major League” (filmed at County Stadium) endures today.

Ultimately, the reason he finally signed a contract with the Brewers was because he lost benefits from the Screen Actors Guild.

-Drake Bentley

Hmong headwrap

When she was a teenager, UW-Milwaukee professor Chia Youyee Vang remembers how her mother and aunt wrapped a long, purple cloth into a turban around her head. Then decorated with a black-and-white striped ribbon, it was one piece of the elaborate traditional clothing Vang would wear to celebrate the Hmong New Year.

Today, the phuam txoo suab is more hat than headwrap. It’s often sold pre-wrapped, and it might be embroidered with silver coins or shiny beads. At annual New Year celebrations at Wisconsin State Fair Park, it’s a common headpiece for girls and women.

The headwrap’s evolution parallels Milwaukee’s Hmong community in some ways. Today’s young generation fuses American culture with the traditions of their parents and grandparents, who fled Laos as refugees in the 1970s and 80s.

Older immigrants worry about language and culture fading. But they also see their descendants blossoming: earning degrees, running businesses and buying homes in neighborhoods across the area.

Milwaukee County is home to about 13,000 Hmong, census data shows. That’s nearly one-third of all Asian residents in the county.

Like the Germans, Poles and Italians before them, the Hmong have made their mark on Milwaukee. The ways they’ll express and share their traditions with the city will only become more intricate as their roots deepen.

-Sophie Carson

Box of Sciortino’s cookies

Opening a box of Italian cookies from Peter Sciortino Bakery has an undeniable sweetness – like a mix of happy family memories and buttery goodness.

Since Peter Sciortino and his wife, Grace, opened the bakery in 1947, it has grown into a beloved fixture on Brady Street. It opened just one year after Glorioso’s Italian Market, another legendary business that still calls Brady Street home. Both first became institutions as Italians began moving north from the Third Ward to the east side neighborhood decades ago, and have since become a tradition for families throughout Milwaukee.

The aroma of fresh-baked bread and cookies typically surrounds Peter Sciortino Bakery, and inside, cannoli is made fresh with each order.

Luckily the cookies are sold by the pound, so there’s no need to choose between cimino, biscotti, amaretti, chocolate mezza luna, or any of the other varieties – just make sure you get a big enough box to try as many as possible.

-Mary Spicuzza

Rolling Mills plaque

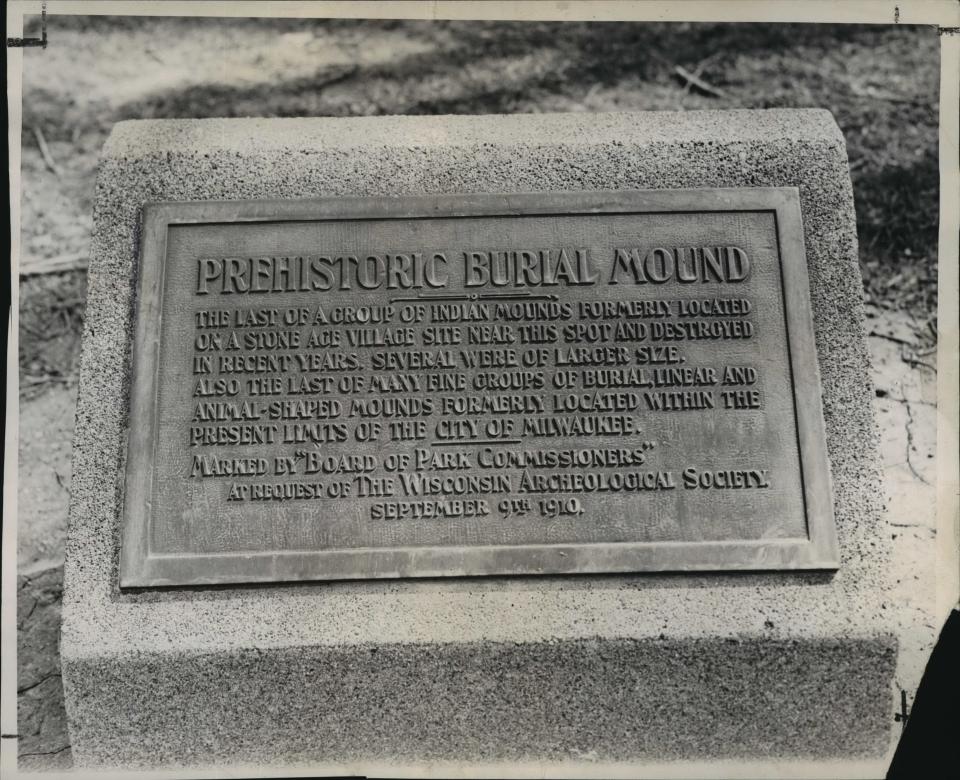

Where Russell Avenue meets Superior Street in Bay View, an understated brown sign pays homage to one of the most significant sites in Milwaukee’s history: a 19th-century iron mill where a march for an eight-hour work day turned deadly.

The historical marker recalls the events of May 5, 1886: the Bay View Massacre.

That year, labor organizations nationwide were demanding an eight-hour work day, and they wanted it by May 1. Many Milwaukeeans were working 10-hour days, six days a week for paltry wages, Milwaukee historian John Gurda noted in his book “The Making of Milwaukee.”

As companies balked at the demand, strikes grew. By May 3, about half of Milwaukee’s men were on strike, Gurda found. They marched through the city, urging more workers to join them. Panicked officials called in militia from across the state after police were unable to “quell the disturbance,” the Milwaukee Journal reported.

On May 4, tension mounted at the Bay View mill where executives refused the eight-hour demand. Militia forcefully dispersed a crowd of protesters.

On the morning of May 5, about 1,500 marchers returned to the mill. When they were about 200 yards out, the militia fired. Among the seven dead was a 12-year-old boy.

The next day, streets were deserted. Local officials conferred about how to prevent “socialistic agitation,” deciding to arrest as many demonstrators as they could, the Journal reported.

Labor leaders, meanwhile, had public opinion on their side. They turned their focus to winning elections.

That year, the labor-backed People’s Party of Wisconsin won elections up and down the ballot, with priorities including progressive taxes, child labor restrictions, and arbitration of labor disputes, Gurda wrote. While socialist leaders initially supported that party, they later split and ran their own candidates, launching Milwaukee’s socialist era in 1910.

-Rory Linnane

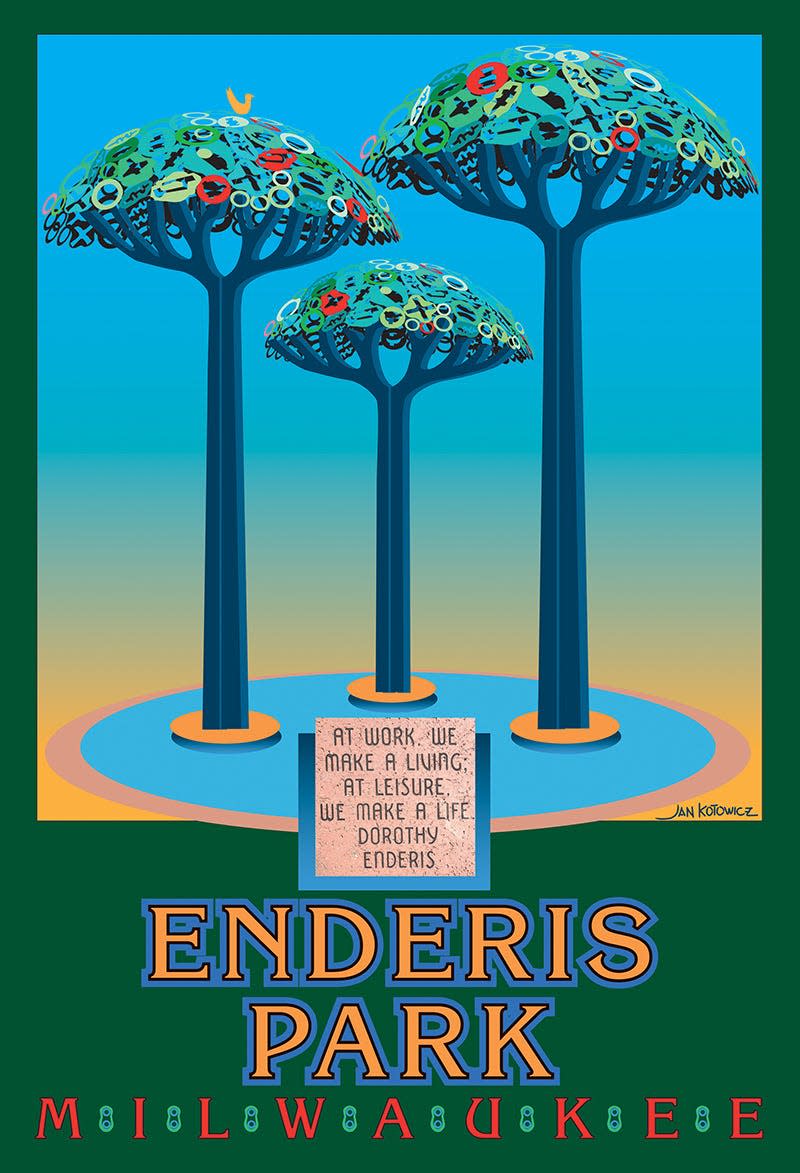

Neighborhood poster

You just moved to Milwaukee. You are sitting in your bungalow in Bay View and staring at the blank walls. You are a full-fledged grown-up, so those leftover posters from your college dorm don’t cut it anymore.

For generations, the Milwaukee neighborhood posters have provided an easy and classy way to decorate your new space. They were unveiled in 1983 by the City of Milwaukee’s Discover Milwaukee program, with colorful, eye-catching artwork by Jan Kotowicz of local landmarks, like the lower east side’s Oriental Theatre and Washington Park’s bandshell. Wait, what is Pigsville? Thankfully, local historian John Gurda provided illuminating text on the back of the posters about each neighborhood. The posters even popped up in “Wayne’s World” to lend authenticity to Alice Cooper’s Milwaukee-centric cameo.

Best of all, the posters follow the egalitarian spirit of the city. The original run of 21 neighborhoods initially cost just $2 apiece. Now there are 39 options available from Historic Milwaukee, Inc., including one with all the neighborhoods, for only $10. There’s no excuse for those blank walls.

-Ben Steele

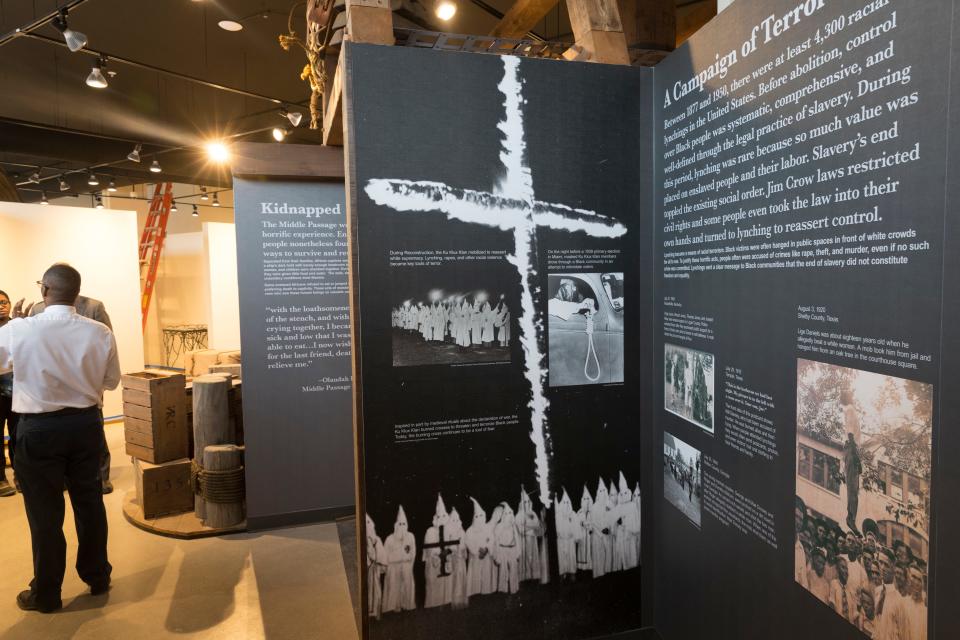

America’s Black Holocaust Museum

America’s Black Holocaust Museum is the first and only museum of its kind in the U.S. It’s an unflinching look at more than 400 years of slavery, dehumanization, lynching and mass incarceration of Black Americans.

The dream for the museum began as a small collection in Dr. James Cameron’s basement. In 1930, when he was 16, Cameron narrowly survived a lynching in Marion, Indiana. He spent the rest of his life in Milwaukee collecting photos, artifacts and books that shed light on the histories of African Americans. He regularly welcomed guests into his home to learn this history.

The museum moved to its first official location in the Sultan Muhammad Islamic Center. Its grand opening was Juneteenth Day in 1988.

Cameron passed away in 2006. The museum subsequently moved buildings and briefly closed, and now resides at 401 W. North Ave., part of a redevelopment project in the heart of Bronzeville called the Griot — a West African term for “storyteller” — in honor of Cameron.

The museum starts in Africa in 300 CE, long before Europeans arrived, and ends with issues impacting Black people today, like police brutality and mass incarceration — covering the 16 generations of slavery in the U.S., reconstruction, 100 years of Jim Crow, the Civil Rights movement and the Black Lives Matter movement.

A tree with branches stretching along the ceiling pays homage to the powerful song “Strange Fruit,” made popular by artist Billie Holiday, that fearlessly protested the widespread lynchings of Black Americans.

-Gina Castro

Pabst sign

Pabst Brewing Co. shut down its Milwaukee operations in 1996. But the huge “Pabst” sign that’s stretched far above West Juneau Avenue for several decades has remained a constant — even as the former brewery was redeveloped over the past decade or so into offices, housing, a craft brewery and other new uses.

The sign is attached to an iron footbridge that is anchored by Pabst’s former malt house, now The Malt House apartments, and the old brew house, now the Brewhouse Inn & Suites. The glowing red sign has undergone repairs in recent years, with the iron bridge’s restoration being completed this spring, according to Erin Stenum, manager of the neighborhood improvement district at the former Pabst complex, now known as The Brewery. Ein Prosit!

-Tom Daykin

South side food trucks

The soundtrack to most city parks includes the ping of a bouncing basketball, the tinny reverb of a faraway stereo or the sizzle of a grill fired up for sausages.

You’ll hear those at Burnham Park, too, but there’s another layer to the score: the soothing hum of a handful of taco trucks parked just outside, and the chatter from hungry hoards waiting in the wings for a carne asada taco, a lengua huarache or a cooling horchata on a hot summer night.

These food trucks are part of the fabric of Burnham Park. Beyond the neighborhood, the south side is dotted with family-owned fleets carrying specialties all their own, parked on Historic Mitchell Street, West Lincoln Avenue, West Becher Street and across the neighborhoods tucked in between.