5 Delicious Reasons You Shouldn't Miss Out On Salvadoran Food

For Karla Tatiana Vasquez, eating and cooking Salvadoran food with her family has never been just about the food –– it’s what makes her feel most Salvadoran.

Vasquez, who was born in El Salvador, grew up in Los Angeles watching her family use meals to pass on what they remembered of their war-torn homeland.

“I’m very fortunate that my family always wanted to talk about what they experienced [in El Salvador]. And every time we did, it was literally while we were eating,” Vasquez told HuffPost. “And I think it’s because food creates a buffer, you know, not looking at each other face to face. ...You’re eating, and you’re listening, and it kind of filled up this space.“

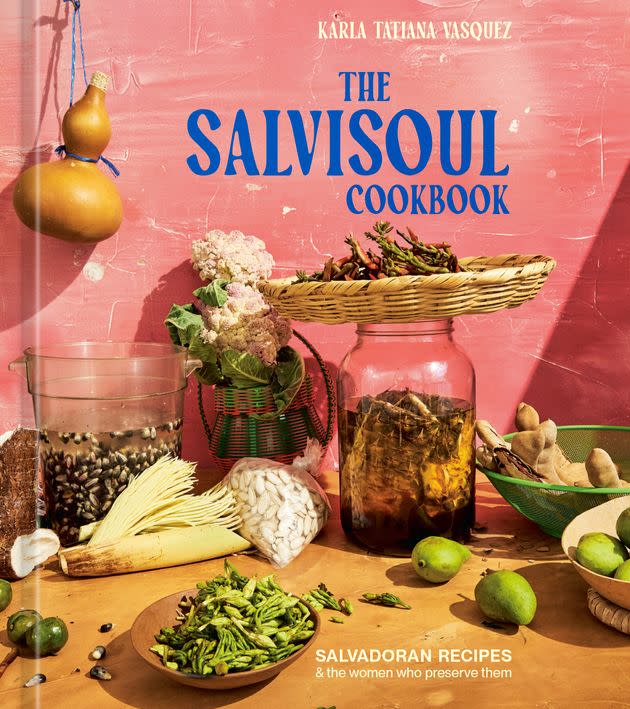

Now the food writer and historian is the author of “The SalviSoul Cookbook: Salvadoran Recipes & The Women That Preserve Them,” the first cookbook of Salvadoran recipes by a major U.S. publisher. It goes on sale Tuesday. It is the book Vasquez always wanted to read growing up.

But getting the book made was not easy. During her near-decade-long odyssey to being published, Vasquez faced rejections from agents who did not understand why the book mattered, as well as a lack of written research of Salvadoran gastronomy by Salvadorans.

One major reason there aren’t more Salvadoran recipes written down? The Salvadoran civil war that caused traumatizing silences and has kept many recipes from being documented in the U.S. diaspora, Vasquez said.

That’s why Vasquez said if she wanted to write about her roots, it could only ever be through the healing connection food offers.

“I have tremendous love for Salvadoran mothers, Salvadoran grandmothers, Salvadoran women, because I’ve seen what the women in my life have had to go through to secure survival for us, and I really just want to show them care,” Vasquez said. “And so I feel like a way to do that is to have our stories written down.“

To honor these cultural memories, Vasquez interviewed 33 Salvadoran women who were either family, like her beloved grandmother Mamá Lucy, friends, or people Vasquez found through SalviSoul, her Salvadoran cookbook storytelling project. Short stories of their love, heartbreak and resilience are interspersed between the recipes these Salvadoran women shared with Vasquez.

Vasquez said the compilation approach to her cookbook is “insisting that the place I get any kind of authority isn’t from an institution that’s backed by white folks. It’s a collective of women who some of them don’t even know how to read or write. And they’re cool with it, they’ve managed and they’re, like, ‘You know what? We know how to survive. We’re wise, and we have a lot to give.’“

And through Vasquez’s book, their wisdom about food and life is finally being heard.

Unlike other cookbooks that are centered around dinner-party entertainment, this cookbook makes space for anhelo, or the longing to know or have.

“Food hasn’t been an entertainment for me. It’s been a classroom, it’s been a therapy room, it’s been a safe place to feel safety and connection with my family,” Vasquez said.

The first lesson to understanding a too-often overlooked culture’s cuisine is to correct assumptions you may hold about what it even is. HuffPost talked with Vasquez about what you may not realize you’re missing out on with Salvadoran cuisine.

1. Salvadoran food is way more than pupusas.

If you have any passing familiarity with Salvadoran food, then you have likely tried a pupusa, a griddled corn or rice flour tortilla that is filled typically is filled with cheese, beans, loroco (an edible flower) and/or pork.

They are El Salvador’s most popular dish for good reason. When pupusas are accompanied with a tangy vegetable curtido (a cabbage slaw) and a salsa roja, they are a perfect meal. But there are so many more Salvadoran classics, which involve yuca (the cassava root plant), that should get the celebrity treatment that pupusas get, Vasquez said.

Vasquez said she would love more yuquerias, like Osicala in New York City, which purely sells Salvadoran yuca dishes, to become as popular as pupuserias in the United States.

“We sure love yuca. There’s the yuca frita, the yuca sancochada [fried or boiled yuca],” Vasquez said.

To spread the word, Vasquez purposefully added a recipe of yuca with pepescas, or tiny dried sardines, to the book as “another one of those funky dishes that lots of Salvadorans love” because pepescas were not an ingredient she knew about until she was conducting research for the “SalviSoul” cookbook.

“You see yuca frita con chicharrón [fried yuca with pork meat chunks] in a lot of venues across the nation that are Salvadoran, and not a single one that I’ve seen ever has pepescas,” Vasquez said.

Here’s Vasquez’s pitch to persuade you to make this dish first: “It’s a strong flavor, but if you fry them ... you can make the whole dish with the yuca and everything [and add] a tortilla tostada and a little limón [lime], a little extra salt –– oh, it’s so good, it’s a nice snack.”

2. Salvadoran food is not Mexican food.

In her book, Vasquez recalled that when she’d been asked to describe Salvadoran cuisine, the attitude and comments she would sometimes receive in return boiled down to: “Why couldn’t they call Salvadoran food Mexican food?”

In Central American countries, “We all nixtamalize corn to make tortillas in some shape or form. So there’s a lot of push and pull where we’re trying to kind of negotiate with the history of the product,” Vasquez told HuffPost.

“There’s always this journey we’re trying to take back into the past to see who had it first, because then that’s who can say owns it now. And I think a lot of those conversations will say, ‘Well, if the root of it is here, then everything else is just a copycat,’” Vasquez added.

But that ignores the distinct nuances of how ingredients travel and what different cultures do with them.

Vasquez gave the example of corn. Though it was first found in what is now the nation-state of Mexico, it was first nixtamalized in Guatemala, she said research has found.

So when people do ask, “Isn’t all Central American cuisine the same, or la misma cosa?” Vasquez said she’ll often counter with the analogy of a sibling being called by the wrong name by a family member.

“You get annoyed if they call you Nancy and you know your name is Brenda. ‘We may come from the same parents, but please call me by my name, because even if we come from the same parents, we are very different,’” Vasquez said. “We know that it’s rude. So why don’t we kind of show the same courtesy to whole countries and cuisines?”

3. There’s pride in taking shortcuts in the Salvi kitchen.

Vasquez said that when she was interviewing the Salvadoran women who donated their stories and recipes for the book, many of them felt shame over using shortcuts, such as substituting chicken bouillon for a fresh caldo, or broth, in their recipes.

But these shortcuts do not make their recipes any less deliciously Salvadoran.

“Any condiment really is there to make cooking and feeding yourself a little bit easier. But there’s always this shame that’s been thrown at women. And what’s worse is that it’s often women that are already strapped for energy, time and resources,” Vasquez said.

That’s why the “SalviSoul” cookbook makes it clear that powdered or cube bouillons have their place in Salvadoran cooking as a “quick, effective way to add flavor to meals and often the secret ingredient that many matriarchs share with those who want to know.”

“I put that in there as a way to show women a little bit of care, a little bit of cari?o and tenderness for themselves,” Vasquez said of the bouillon shortcut. “Because every time I was in the kitchen with one of them, I just wish that they saw, like, you are doing so much and you don’t need to feel bad about this.”

4. Salvadoran cuisine loves to use flowers and the whole plant.

There’s a misconception that Salvadoran food is meat-heavy, Vasquez said. If you want to understand the nuances of Salvadoran cuisine, join the “flower-eating club,” as Vasquez puts it in her cookbook. Vasquez includes recipes using bitter flowers, like pacayas, wild greens of chipilin and zesty watercress.

Take the flor de izote, or yuca flower that is native to El Salvador. When Vasquez’s family would find them or forage for them, her mother would add them to scrambled eggs with sautéed onions and tomatoes for breakfast.

The first time she tried the white-petaled flor de izote, Vasquez said, she was like, ”‘Oh, we eat flowers? Like that’s pretty cool.’ I felt like so much of my life I’ve wanted to belong, I wanted to feel grounded, and I felt like, to me in food and in the kitchen and cooking, I felt like I could access that feeling of ‘I belong here.’”

5. You can be a “real” Salvadoran and still be learning how to make these dishes.

It’s more than OK if you’re Salvadoran and the recipes in Vasquez’s book are new to you. Some of them were new to Vasquez, too.

Vasquez said her parents left El Salvador in their 20s and that it can be “an unfair ask” in general to expect older Salvadorans of the diaspora who had to migrate to remember everything “because they didn’t get to really soak in all of the culture.”

”‘What do you mean you don’t know how to make [insert name of cultural dish

here]? You must not be a real [insert culture].’ That accusation has been thrown

at me by my family, the community, and even myself at times. I’m here to say that it’s okay,” Vasquez writes in her book about learning how to make atol chuco, a funky, fermented dish, as an adult. “The point is to keep learning for yourself.“

This permission to learn resonated with me. My mother is Salvadoran, and she had to leave the country to study when she was a teen because of the nation’s civil war. I did not grow up cooking or eating much Salvadoran food for dinner, but talking about Vasquez’s book sparked a long, animated conversation with my mom about favorite dishes I didn’t know she loved and wanted to try again soon.

So if you’re new to Salvadoran food, this book can be a helpful introduction. And if you are Salvadoran like me or Vasquez, let this book be a healing way to build a bridge between you and your heritage.

“What I really am trying to do is to make sure we have at least documented some of these traditional food-ways so that no matter where we go, what happens to us or our kids, like, we have a way to kind of figure it out,” Vasquez said.

Try one of her favorite recipes below, excerpted here courtesy ofthe cookbook’s publisher,Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

Yuca Frita con Pepescas

There is no doubt about what you’re cooking when you open a plastic box of pepescas. People talk about the funky cheese that Salvadorans love, but in my personal opinion, the smell of these tiny dried sardines when fried is incomparable. I like to file them in the category of “so delicious to eat, but not so great to prepare.” They are potent, but so right as an accompaniment to yuca, followed with bites of tangy curtido and zesty watercress.

An option in many places in El Salvador is skipping frying the yuca altogether and only salcocharla (boiling it with garlic, onion, and salt) until it turns fluffy. This fluffy yuca with salty bits of fried pepescas is also a manjar, a heavenly delight. Either way, your home will know what you’re up to as soon as you open the pepesca package.

Yuquerias are a dominant culinary tradition of the Mejicanos neighborhood in San Salvador. Just like there are pupuserias, there are yuquerias that serve only items showcasing the gastronomic range of yuca, which covers a lot. They feature two main savory specialties: fried and boiled. In recent years, eleven festivals have been held to honor this cuisine and promote cultural

tradition in different areas of the municipality.

This offering also takes various forms. Some versions come with chicharrón and others with fritada, a mix of organ meats stewed in a sauce. But this one celebrates the wonderful — albeit pungent — pepescas. Isabel fries the yuca and pepescas and makes her own version of salsa roja with curtido.

You will need six banana leaves to line the serving plate. Most Latin American markets carry banana leaves year-round, so they should not be too difficult to source.

Makes 4 to 6 servings

3 pounds yuca (see “Consejo” below), cut into 2-inch pieces

1/2 medium yellow onion, peeled

4 garlic cloves, left whole

1 tablespoon sea salt

1 pinch baking soda

1 cup avocado oil

Isabel’s Salsa Roja

4 medium tomatoes, stemmed

2 medium green bell peppers, cored and halved

1 medium red onion, peeled

3 large garlic cloves, left whole

2 chiles de árbol

1/4 teaspoon dried oregano

2 tablespoons neutral oil (such as canola oil)

Isabel’s Curtido

3 cups cabbage, thinly sliced

1 cup hot water

Juice of 1 lemon

1/2 teaspoon kosher salt

1 cup thinly sliced radishes

1/4 red onion, thinly sliced

1 cup neutral oil (such as canola oil)

2 cups pepescas

1 bunch watercress

1 large tomato, cut into wedges

6 banana leaves

In a large pot over medium-high heat, bring 6 cups of water to a boil (or enough to cover all the yuca). Add the yuca, onion, garlic, sea salt, and baking soda. After about 25 minutes, the yuca should be tender; drain and pat dry with paper towels. Discard the onion and garlic. In a large pot over medium-high heat, warm the avocado oil until it registers 350°F on an instant-read thermometer. Add the yuca pieces and fry until they turn golden brown, about 2

minutes per side. Set aside.

To make the salsa: In a medium pot over medium-high heat, combine the tomatoes, bell peppers, onion, garlic, and chiles and cover with water and bring to a boil. Once it’s boiling, lower the heat to medium, stir and cook until the tomato skins fall away from the flesh, about 15 minutes. Reserve about 1 cup of water. In a blender, add the cooked vegetables with the oregano and 1 cup of water and blend to incorporate. Set a fine-mesh strainer over a bowl and

pour the vegetable sauce through the strainer.

In a large saucepan over medium-high heat, warm the neutral oil until it shimmers. Add the strained sauce and fry until the color deepens to bright red, about 5 minutes. Remove from the heat and set aside.

To make the curtido: Place the cabbage in a large bowl and pour the hot water over it. Let sit for about 1 minute, then drain and add the lemon juice, salt, radishes, and red onion. Stir to combine and set aside.

Line a large plate with paper towels and set it near the stove. In a large frying pan over high heat, warm the neutral oil until it shimmers. Place a pepesca in the oil; if it sizzles, the oil is ready for frying. Add the pepescas and fry until they turn golden brown, about 5 minutes. It’s a good idea to stay close to the pepescas as they can burn very quickly and easily, given their small size. Using tongs or a slotted spoon, transfer the pepescas to the prepared plate to drain and set aside.

Line the bottom of a plate or bowl with banana leaves. Fill it with the yuca, then layer with the curtido, watercress, tomato wedges, salsa roja, and finally the fried pepescas. Serve immediately.

Consejo

When you shop for yuca, be mindful of the inside of the root. Most of the SalviSoul women admit that they break the roots to check their condition while still at the market. If you’re in a Latino market, you may see this commonly practiced to find fresh, healthy yuca roots. However, some grocery stores won’t permit them to be broken, so be warned. If black lines appear in the

root, or the yuca appears yellow and not white throughout, it won’t be usable.

Reprinted from “The SalviSoul Cookbook: Salvadoran Recipes and The Women That Preserve Them” by Karla Tatiana Vasquez ? 2024. Photographs copyright ? 2024 by Ren Fuller.