Adele, Inc: why the music industry is banking on pop’s $1.5 million-a-day woman

In 2016 the Kogod School of Business at American University in Washington D.C. released a study examining Adele’s popularity. In a series of eye-popping charts, academics outlined the extent to which the Tottenham-born singer had “captured the hearts and wallets of consumers worldwide”. One chart showed that her 2015 album 25 accounted for three per cent of all albums bought across the entirety of the United States that year. The analytics project, named Adelytics, pulled no punches in its conclusions. “Adele,” the report said, “is a statistical anomaly.”

Since her debut album 19 was released in 2008, Adele has single-handedly pumped hundreds of millions of pounds into the music industry. With new single Easy On Me out today and her fourth album, 30, out on November 19, hype has reached fever pitch. Within eight hours of being released this morning, the video for Easy On Me – a typical stripped-back Adele piano ballad – had been viewed 15 million times on YouTube.

Speaking to BBC Radio 2’s Zoe Ball this morning, Adele said she picked it as the first single as it had a soaring chorus and “just felt like a ‘me’ song, and after having been away for so long it just felt like that was probably the biggest part of my songs that people were waiting for.”

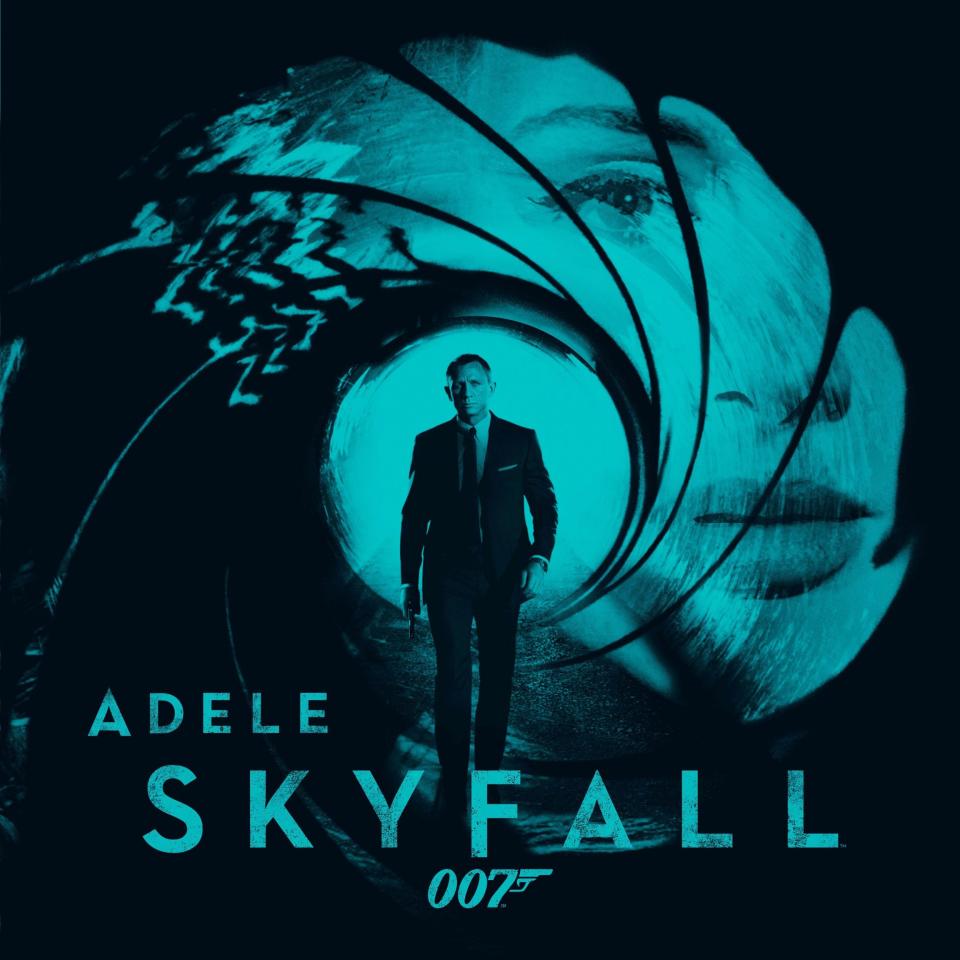

It’s easy to see why Adele doesn’t want to tinker with a winning formula. Over a 14-year career in which the music industry was meant to be going through a tough time due to the streaming revolution, she has defied gravity. The 33-year-old has sold over 120 million records, and her last world tour comprised 121 shows and grossed £123 million. She has an estimated personal fortune of £130 million and she’s the only person in history to have had the biggest selling albums in the US for two years running twice over (25 and its predecessor, 2011’s 21). Then there’s the halo effect: the Adele, for example, sprinkled stardust on the Bond franchise in 2012 with her Skyfall theme tune. The connection is apt. As with a new 007 film, a new Adele album isn’t just a release – it’s a global cultural event.

“She’s a worldwide superstar now and the income she generates worldwide is extraordinary. It’s got to be getting on for a billion pounds,” says John Giddings, the promoter who has counted David Bowie and the Rolling Stones among his clients and who now runs the Isle of Wight Festival. “She’s absolutely like Bond. Everybody wants to go there. It’s not just one age group. It’s young people, old people. She’s cracked it big time. She’s fundamentally got it, and she’s cool and commercially viable. It’s a perfect balance isn’t it? It’s the perfect storm.”

Nick Stewart, the music manager and label boss who signed U2 to Island Records in 1980, says Adele’s cultural currency is on a par with both Britain’s favourite spy and a certain bespectacled boy wizard. “There are these huge tentpole moments in culture. So far this year we’ve had ABBA, James Bond and Adele. They are completely outside the norm,” says Stewart. “In movie terms, beyond Bond, a Star Wars film has the potential to do the same, although there are a lot of those now. If JK Rowling released a new Harry Potter book, that would be up there.”

So precisely how much money has Adele brought into the music industry?

The figures are so huge, involving such a conga line of zeroes, that they’re in danger of appearing meaningless. But broken down, their impact is clearer. The Adelytics report says that the CD of 25 sold an average of 120,000 copies a day between its November 2015 release date and the end of that year. Crudely, at $12 a CD, that represented almost $1.5 million of cash into the industry every day (split between retailers, distributors, manufacturers, record companies and Adele herself).

CD sales (yes, Adele is one of those rare artists who still shifts physical product) generated tens of millions in income the following year too. Indeed, Adele described herself on BBC Radio 1 today as “the queen of CDs” and said the release date for 30 had to be locked in for months to give CD pressing plants time to make all her discs. And none of this takes into account the added revenue she gets from her vast streaming numbers.

Adele has hugely enriched her record labels. In 2006 she signed to XL Records, the small Notting Hill-based independent label that made its name with breakbeat hardcore hits such as 1992’s On A Ragga Tip by SL2. XL’s financial fortunes were transformed (although not before a visitor to XL’s offices mistook the singer for an intern and asked her to make a cup of tea).

Analysis by Music Business Worldwide shows that the label’s sales and operating profit in 2010 – the year before Adele’s 21 album came out – were £22.4 million and £4.1 million respectively. The next year, following 21’s release, sales rocketed fivefold to £112.7 million and profits rose tenfold to £41.7 million. Similar leaps happened in the years following 25’s release. Robert Watts, compiler of The Sunday Times’ Rich List, has said that the singer could have been responsible for 80 per cent of XL’s turnover.

XL is 50 per cent owned by producer Richard Russell and 50 per cent owned by Beggars Group, which also owns labels 4AD, Matador and Rough Trade. Beggars is controlled by Martin Mills. According to 2020 The Sunday Times Rich List, Russell is worth £160 million – more than his star signing – while Mills has a fortune of £230 million.

In Russell’s memoir Liberation Through Hearing, released in April 2020, he called her a “punk Barbra Streisand”. He knew she was good, original and a stunning performer. But he admits that what later occurred with Adele was “something of a miracle”.

Adele’s contract with XL is thought to have expired after the release of 25, although this was never confirmed at the time. In 2016 she was rumoured to have signed a £90 million deal with the UK arm of Columbia Records, part of conglomerate Sony, which already distributed her music in the US. This week, Music Week reported that Adele had indeed moved full-scale to Columbia in the UK, signalling an end to her relationship with XL. Both these labels have – and will continue to – benefited greatly from the singer.

This includes her management team, who are members of a music industry dynasty. Adele is managed by Jonathan Dickins and her live agent is his sister Lucy. Their grandfather, Percy, co-founded the NME, their father, Barry, was himself a legendary agent who worked with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Dolly Parton, and their uncle Rob was formally UK boss of Warner Music. Reports in January suggested that Jonathan Dickins earned the equivalent of almost £27,500 a day in 2019 (this figure appears to have been reached by dividing the £10 million of dividends paid out by his company September Management by the number of days in the year).

Aside from what Adele personally contributes to the global music ecosystem, she exudes soft power. Back to Bond. Skyfall took $1.1 billion at the global box office, almost double what previous films Quantum of Solace and Casino Royale each took. While her ballad played only a limited part in that film’s success – Daniel Craig, director Sam Mendes, cinematographer Roger Deakins and the writers must obviously take the credit -– she was nonetheless a key player in the mix. Adele went on to win the first ever Oscar for a Bond song (as well as, incidentally, a Grammy, a Brit and a Golden Globe). Three years later, Sam Smith also won an Oscar for his (inferior) Spectre theme Writing’s on the Wall. Don’t bet against Billie Eilish making it a treble at next March’s Oscars. Smith and Eilish’s tracks stick to a Skyfall-ish template. Adele kicked down the door through which they walk.

Despite her wealth, Adele’s relatability is central to her commercial success. The Adelytics project cited Nielsen research that found that 55 per cent of fans see Adele as “someone I can relate to”. When the singer presented Saturday Night Live last October, the show pulled in five million viewers, a 25 per cent uplift on the usual figure. When Adele rapped Nicki Minaj’s part in Kanye West’s Monster when appearing in James Corden’s Carpool Karaoke in 2016, West’s song re-entered the iTunes hip-hop top ten. That’s influence.

Adele has the two of the crucial elements that writer Alan B. Krueger identifies as key to making money in the music industry. She has scale and she has “non-substitutability”. In other words, she appeals to a large audience and she offers something utterly unique and distinct. There is “no substitute” for these in consumers’ eyes, Krueger writes in his book Rockonomics.

Adele may have spawned dozens of tribute acts – top marks to the cleverly named Someone Like Adele (price range £750-plus-VAT to £1,150-plus-VAT) – but she has staunchly resisted product endorsements or tacky merchandise ranges. In the late-Nineties, her beloved Spice Girls signed deals with everyone from PepsiCo, Polaroid and Walkers Crisps to Benetton, Asda and Cadbury. Not Adele. She claimed in her recent dual interviews in UK and US Vogue that she simply doesn’t care.

On her much commented on weight loss, she said, “People are shocked because I didn’t share my ‘journey’. They’re used to people documenting everything on Instagram, and most people in my position would get a big deal with a diet brand. I couldn’t give a flying f__.’” The singer also clearly understands that scarcity is a valuable commodity. Which is why the money rolls in when she does engage with her fans.

So what’s next? There are rumours that Adele is considering a Las Vegas residency in 2022 instead of a huge US tour. Reports in Billboard suggest the shows could take place in either the Colosseum at Caesar’s Palace or the Park Theatre at the Park MGM Las Vegas, both of which are run by Live Nation.

A long-term residency would give her and her son Angelo a settled routine, and allow her to commute from her Los Angeles home to Vegas with ease. Although these venues only hold 4,100 and 6,400 people respectively, tickets could be sold at a premium as it’s Vegas. (Adele appeared to pour cold water on these rumours this morning but watch this space). A recent report suggested a Vegas residency could double Adele’s fortune. And it’s not just her who would benefit financially. People who visit Vegas need flights to get there. They need hotel rooms. And they need food and drink.

So a whole new front could be about to open in the Adele economy. Her astonishing financial clout could grow yet again. As the singer herself said at the 2016 Brit Awards, “Not bad for a girl from Tottenham who’s scared of flying.”